1st West Virginia Volunteer Cavalry Regiment

| 1st West Virginia Volunteer Cavalry Regiment | |

|---|---|

West Virginia Honorably Discharged Medal | |

| Active | July 10, 1861, to July 8, 1865 |

| Country | United States |

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch | Cavalry |

| Engagements |

Battle of Kernstown I (6 co.) Battle of Hanover Battle of Gettysburg Battle of Hagerstown Battle of Boonsboro Battle of Mine Run Battle of Cove Mountain Battle of Lynchburg Battle of Rutherford's Farm Battle of Kernstown II Battle of Moorefield Battle of Opequon Battle of Fisher's Hill Battle of Cedar Creek Battle of Waynesboro, Virginia Battle of Dinwiddie Court House Battle of Five Forks Battle of Sailor's Creek Battle of Appomattox Station Battle of Appomattox Court House |

| Commanders | |

| Colonel | Henry Anisansel 1861–62 |

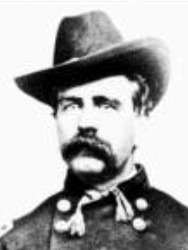

| Colonel | Nathaniel P. Richmond 1862–63 |

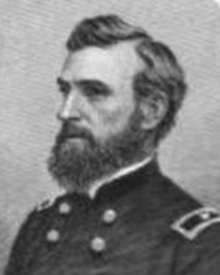

| Colonel | Henry Capehart 1863–64 |

| Lt. Colonel | Charles E. Capehart 1864 |

| Major | Harvey Farabee 1864–65 |

The 1st West Virginia Volunteer Cavalry Regiment served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Although the regiment was originally called 1st Virginia Cavalry, it should not be confused with the Confederate version also called 1st Virginia Cavalry. Some reports added "Union" or "Loyal" when identifying the Union version of the Virginia cavalry. After the state of West Virginia was created in 1863, the regiment could be differentiated from the Confederate version by calling it the 1st West Virginia Cavalry. The National Park Service identifies it as the 1st Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry.

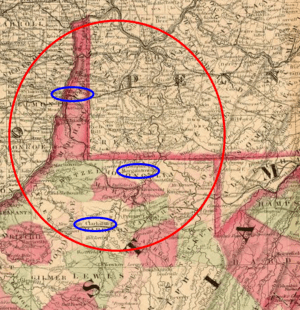

The regiment was organized in Wheeling, Clarksburg, and Morgantown in northwestern Virginia (now West Virginia) mostly between July 10 and November 25, 1861. Members consisted of men from the northern counties of what is now West Virginia, plus additional men from western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. The regiment was often split during the first two years of the war, with detachments spending time guarding the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and hunting bushwhackers. During July 1863, ten companies of the regiment fought at the Battle of Gettysburg as part of a division.

The regiment began fighting in Virginia's Shenandoah Valley during the last half of 1864—usually in a brigade as part of the 2nd Cavalry Division, Army of West Virginia. At the beginning of 1865, the regiment became part of the 3rd Brigade in General George Armstrong Custer's 3rd Division, Cavalry Corps—which, along with another division was under the command of General Philip Sheridan. Sheridan's two cavalry divisions were responsible for eliminating Confederate General Jubal Early's Army of the Valley from the war. After the success in the Shenandoah Valley, Sheridan moved his two divisions eastward toward Petersburg, Virginia, and they played an important part in the Appomattox Campaign and the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. After the war, the 1st West Virginia Cavalry participated in the Grand Review of the Armies, and was mustered out on July 8, 1865.

Formation and organization

Although Virginia seceded from the union and joined the Confederate States of America, many people in the northwestern portion of the state preferred to remain loyal to the United States. This loyal segment of Virginia formed the Restored Government of Virginia, which was loyal to the United States, and this led to the eventual formation of the state of West Virginia from the western portion of Virginia. The first new cavalry regiment formed from this loyal region was originally known as the 1st Virginia Cavalry, and was sometimes noted as a loyal (to the union) regiment to differentiate it from the 1st Virginia Cavalry that was a rebel force for the Confederacy.[1] The regiment eventually was identified as a West Virginia cavalry. Recruiting for the new regiment began during July 1861, and continued into the fall.[2] About one third of the original members of the 1st Virginia Cavalry were born in the Virginia counties that are now part of West Virginia, especially around the cities of Wheeling, Morgantown, and Clarksburg. Pennsylvania and Ohio were also sources for recruits. One company consisted mostly of men who spoke German.[1]

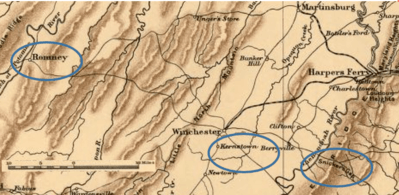

The regiment’s first company, which became the original Company A, was known as the Kelley Lancers. This company was the first cavalry unit organized in the Virginia counties that became West Virginia, and it was mustered in at Morgantown on July 18. It was led by Captain John Lowry McGee, and reported immediately to General Benjamin Franklin Kelley.[Note 1] The Lancers began operations on October 26, 1861, at Romney.[6] They developed a good reputation hunting bushwhackers—or bad reputation among those that favored the Confederacy. The Lancers were said to be good for "three to one" against rebel cavalry, and the rebels swore "eternal vengeance against them".[7] Another company formed around the same time, but with men from southwestern Pennsylvania, was called Gilmore's Company.[Note 2] It was attached to the 1st (West) Virginia Cavalry although it often fought elsewhere.[12]

By the middle of the winter of 1862, the 1st Virginia Cavalry consisted of 14 companies totaling to about 1,100 men. The regiment commander was Colonel Henry Anisansel, who was commissioned September 7, 1861. Anisansel was a former lieutenant in the Ringgold Cavalry.[Note 3] His second-in-command was Lieutenant Colonel Nathaniel P. Richmond.[1] Richmond had been a lieutenant in the 13th Indiana Infantry Regiment and an aide-de-camp to General William Rosecrans.[15] The regiment's chief surgeon was Henry Capehart, who was appointed on September 18, 1861. Capehart eventually became regiment commander and a general.[16] Additional men, usually captains or majors, commanded various detachments of the regiment.[Note 4]

Early action

The regiment's earliest action was typically as detachments of one or two companies. The regiment is credited with being present at the Battle of Carnifex Ferry on September 10, 1861.[2][22] However, the two companies present, Gilmore's Company and a company led by Captain William West that eventually became Company I, were held in reserve.[23] The Kelley Lancers helped capture the town of Romney in October 1861. The Union force in the "brilliant victory over the rebels at Romney" was commanded by General Kelley, and included infantry from Ohio and Virginia plus two companies of cavalry: the Kelley Lancers and the Ringgold Cavalry.[24] The general mentioned the leaders of both cavalry units in his report on the action at Romney, writing about "...the brilliant charges of the cavalry under Captains Keys and McGee."[25]

As the regiment grew, it worked primarily in detachments to hunt bushwhackers. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (a.k.a. the B&O) was an important asset for the Union army, and detachments of the regiment were also used to guard it.[26] In January 1862, the regiment was assigned to the Army of the Potomac. It was shifted among several divisions during the year.[Note 5] Although the regiment became West Virginia's "most active, and one of the most effective," it did not begin well.[1] During 1862, the regiment had two commanders arrested in separate incidents.[Note 6] General James Shields, in a May 20, 1862, report to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, said "First Virginia Cavalry good for nothing. I propose to leave it in camp of instruction here."[28]

First test

One of the first significant tests for the regiment occurred in February 1862, when it was part of a force commanded by General Frederick W. Lander. On February 14, Lander tried to surprise two regiments of infantry from General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson's army near Bloomery Gap (mountains east of Romney). During pursuit of the rebels, Lander became infuriated when the 1st Virginia Cavalry's Colonel Anisansel failed to lead a charge through a gap. Lander was forced to rely on cavalry from Ohio instead. When the 1st Virginia Cavalry finally joined the fight, Anisansel fell from his horse—worsening a hernia injury suffered earlier. His regiment retreated after the fall and had five casualties. Infantry from Indiana and Virginia moved to the front, passing the retreating cavalry and capturing several supply wagons belonging to the Confederates.[29]

After the battle, Colonel Anisansel was court martialed for failing to charge the enemy. Lander was dying from pneumonia when the case came to court, and Anisansel was exonerated because he claimed a battle injury made him unable to make the charge.[1] Opinions on Anisansel varied. One Ohio soldier wrote that Anisansel "was one of the foreign adventurers who so largely officered our army at its beginning and were absolutely useless for any purpose except to draw their pay and to wear gold braid."[30] Other men believed that Anisansel was acting prudently and "behaved general-like."[29]

Other action

After Anisansel was acquitted, he led the regiment for a few more months. In March, a portion of the regiment was attached to General Hatch's cavalry command in General Nathaniel P. Banks's 5th Corps. Six companies, commanded by Major Benjamin F. Chamberlain, fought in the First Battle of Kernstown on March 22. Chamberlain was complemented in the report by Colonel T. F. Brodhead, Chief of Cavalry.[17] Anisansel led some scouting missions near Snicker's Gap, Virginia, during May.[31] In June, eight companies that were part of Shield's cavalry command were shifted to General Shield's Division in the Department of the Rappahannock. Several companies fought at the Battle of Cross Keys and the Battle of Port Republic, and were commanded by Chamberlain. During July, Anisansel led the larger portion of the regiment in the Madison-Culpeper area of Virginia.[32] Anisansel resigned from the army on August 6, 1862. He was succeeded by his second-in-command, Lieutenant Colonel Richmond.[20]

Colonel Richmond

As Lieutenant Colonel Richmond took over command of the regiment, portions were still fighting as detachments elsewhere. Companies C, E, and L took part in some of the major battles of General John Pope's Northern Virginia Campaign, including fighting at the Battle of Cedar Mountain on August 9.[18] Those same three companies, commanded by Major John S. Krepps, fought at Second Bull Run (a.k.a. Second Manassas) on August 28–30 as part of an independent (Milroy's) brigade in the Third Division of the Army of Virginia.[33]

In September, the regiment was assigned to the defenses of Washington, DC. Two companies fought at the Battle of Antietam in Maryland on September 17.[34] Richmond was promoted to colonel effective October 16, 1862.[35] The regiment patrolled Northern Virginia for the next two months. It was near Thoroughfare Gap and Gainesville in October, and Warrenton, Snicker's Ferry, and Berryville in November.[2]

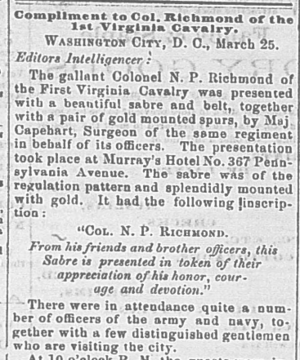

During December 1862, the regiment, commanded by Colonel Richmond, was part of a force commanded by Colonel Percy Wyndham at an outpost in Chantilly, Virginia. Wyndham was both controversial and had a "volatile personality".[36] On December 31, Wyndham grabbed Richmond by the throat and punched him after he refused to take the cavalry on a scout because of the lack of rations. Shortly afterwards, Richmond was arrested for disobedience.[27]

A few days later, 46 officers sent a petition to higher authorities that requested Wyndham be relieved of command, noting that he had officers arrested without just cause. The officers also stated that they would arm themselves when reporting to Wyndham's headquarters.[37] Richmond remained under arrest until he resigned on March 18, 1863.[27]

Mosby encounter

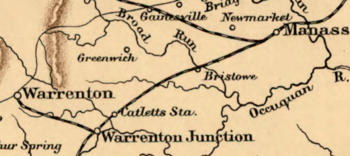

With Colonel Richmond out of the army (temporarily), Lieutenant Colonel John S. Krepps led the regiment. Krepps had been promoted from major on October 16, 1862. On May 3, 1863, the regiment was near the junction of the Orange and Alexandria and Manassas Gap railroads, called Warrenton Junction.[38] A detachment of about 100 men finished their mission for the day. The detachment included men from companies C, G, F and L. Their horses were unsaddled and feeding, and little precautions had been taken for the Union force's security. They were surprise attacked by a group of 70 to 80 men under the command of Major John S. Mosby—the notorious guerilla warfare leader of Mosby's Rangers.[Note 7] Mosby's Rangers operated in the area, and Mosby was buried in Warrenton when he died in 1916.[42]

When Mosby's men approached, the Union soldiers believed they were friendlies from the 1st Vermont Cavalry.[Note 8] Many men from the 1st (West) Virginia were forced to quickly surrender since they were caught unprepared and in the open. Others ran to nearby houses. Major Josiah Steele, seeing that it was impossible to saddle the horses in time to meet the attack, cut the horses loose to prevent them from being captured.[43] Mosby's men were armed with six-shot revolvers, and surrounded the Union soldiers in one (overcrowded) house. Major Steel and Captain William A. McCoy of Company C (who was wounded) refused Mosby's demand that they surrender, so Mosby's men set the house on fire. The Union soldiers ran out of ammunition, and were forced to surrender.[38]

At the time Mosby's men attacked, many of the Union horses set loose by Major Steele were stampeded toward the camp of the 5th New York Cavalry, which caused some of the New Yorkers' horses to also run off. About 40 of the New Yorkers quickly rode to the rescue of the West Virginians, arriving when the house was on fire and its occupants were ready to surrender. More joined the fight when they retrieved their horses.[38] This time, it was Mosby who was surprised, and he suffered significant losses including some of his leaders and 40 horses. The 1st Vermont Cavalry arrived after the fighting, but was able to join the pursuit of Mosby's men. The 1st (West) Virginia Cavalry suffered 17 men killed or wounded, including Major Steele—who died about one month later from his wounds.[38] Newspaper reports believed Mosby was wounded, and his best officer and best spy were among the casualties.[43] Krepps resigned on May 22. The reason for the resignation was given as medical.[44]

During the spring after the Mosby encounter, the regiment became armed with Spencer repeating rifles.[45] Officers from the regiment sent a petition to Secretary of War Stanton to have Colonel Richmond reinstated. Wyndham, the person responsible for the departure of Richmond, had been transferred in the spring. Richmond was reinstated as regimental commander on June 12.[27] On June 20, the state of West Virginia had joined the union, and the 1st Virginia Cavalry (loyal) became known as the 1st West Virginia Cavalry—although many still called it the 1st Virginia.[46]

Gettysburg Campaign

On June 24, the 3rd Brigade, Third Division, Twenty-second Army Corps of the Army of the Potomac departed from its camp in Fairfax, Virginia. Their destination was Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The 1st West Virginia Cavalry, commanded by Colonel Richmond, was in this brigade, and departed with 10 of the regiment’s 12 companies.[Note 9] The brigade moved to Frederick, Maryland, where the entire division was reorganized. Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick was assigned command of the division, and Brigadier General Elon J. Farnsworth was assigned command of the brigade. The other regiments in the brigade were the 1st Vermont Cavalry and the 5th New York Cavalry. The 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry was attached.[48]

Hanover

The brigade moved from Frederick toward Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. On June 30, the brigade approached Hanover, Pennsylvania. The 1st West Virginia led the advance through the town, while the 18th Pennsylvania was in the rear. The rear guard was attacked by cavalry and artillery, causing the front of the brigade to reform and charge back through the town. The Confederates were driven away, but the 1st West Virginia had 2 killed, 5 wounded, and 18 men taken prisoner.[48] The rest of the brigade suffered over 100 casualties.[49] The Confederate cavalry was commanded by General James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart, and the battle became known as the Battle of Hanover.[50]

Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg began on the next day, lasting from July 1 through July 3. Union forces commanded by General George G. Meade (Army of the Potomac) defeated an invading Confederate force (Army of Northern Virginia) commanded by General Robert E. Lee. Over 150,000 men (both sides combined) fought in this battle, and casualties are estimated to be around 51,000.[51]

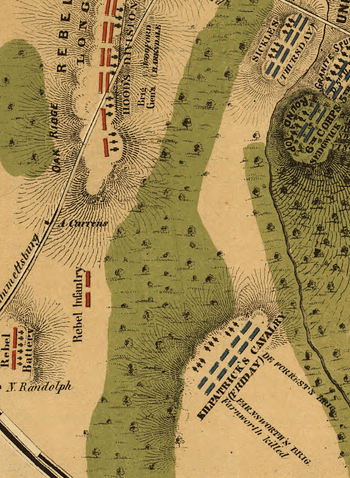

Farnsworth's brigade did not encounter any enemy forces for the first two days (July 1 and 2) of the battle. It patrolled near Abbottstown, Berlin, Oxford, and Hunterstown. Early morning on July 3, the brigade was positioned near the rear center of the Army of the Potomac, near Gettysburg. At 10:00 am, the brigade moved to the extreme right wing of the enemy (east). Confederate infantry, cavalry, and artillery were discovered by the brigade around 3:00 pm. General Kilpatrick ordered brigade commander Farnsworth to make a mounted charge against a Confederate infantry position that was fortified and near ground difficult for horses.[48] A few hours earlier, General Wesley Merritt had sent cavalry forward on terrain that was also not ideal for cavalry—but this unsuccessful attack was made dismounted.[52]

At first, Farnsworth objected to making the charge while mounted. He said "General, do you mean it? Shall I throw my handful of men over rough ground, through timber, against a brigade of infantry?"[53] However, Kilpatrick shamed him into making the charge. Kilpatrick had earned the nickname "Kill-Cavalry" because of his "reckless disregard for his men's lives".[54] The 1st West Virginia Cavalry, led by Colonel Richmond, made the first charge. The West Virginians became nearly surrounded by the 1st Texas Infantry and had to retreat to safety using their sabers. They took some prisoners and suffered casualties of five killed and four wounded. Farnsworth led a second group of men in another charge and was killed. Of the 300 men that Farnsworth led on this charge, 65 became casualties.[55] The charge became known as the infamous Farnsworth's Charge.[56] After the death of Farnsworth, the 1st West Virginia's Colonel Richmond assumed command (officially July 4) of the 1st (Farnsworth's) Brigade. Major Charles E. Capehart assumed command of the 1st West Virginia Cavalry.[57][Note 10]

Pursuit of Lee's Army

After the third day of fighting at Gettysburg, armies on both sides were exhausted. The Confederate army had over 12,000 wounded men.[59] Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia prepared to leave during the rainy night and return to the relative safety of Virginia. Their trip back would involve traveling through mountains to cross the Potomac River at Williamsport, Maryland. Lee chose General John D. Imboden to lead a wagon train carrying wounded men, which left in pouring rain around 4 pm.[60] Its northwest route, which was safer and easier to traverse, followed the road to Chambersburg before moving south through Greencastle.[60] Imboden was instructed to make no stops until he reached Williamsport.[61]

Lee moved the healthy part of his Army of Northern Virginia on a route to Williamsport that was shorter, and involved moving southwest through Fairfield, traveling through several mountain passes to Hagerstown, and then moving southwest to Williamsport. The retreat was orderly, as Lee knew he would eventually be pursued—but he hoped for a cautious pursuit that would enable his army to escape to Virginia. Lee led the retreat and rode with General A. P. Hill's troops.[62]

When Meade and his exhausted Army of the Potomac became aware of the Confederate retreat, the cavalry was sent in pursuit. On July 4, Kilpatrick's division was ordered to search for a large Confederate wagon train. Kilpatrick's division consisted of an artillery unit and two brigades commanded by General George Armstrong Custer and Colonel Richmond (including the 1st West Virginia Cavalry). The division rode to Emmitsburg, Maryland, where it was reinforced with an additional brigade consisting of cavalry men from the 8th Pennsylvania, 6th Ohio, 2nd New York, and 4th New York regiments—plus two companies from the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry. A rain storm caused flooding everywhere, and made road conditions difficult. From Emmitsburg, they took the road west toward Monterey Pass, which was part of a long and difficult crossing of South Mountain.[63]

Monterey Pass

Late at night high in the mountains, near Monterey Pass, a dismounted advance guard company from Custer's brigade confronted a small group of rebels guarding the pass. The rebels, who were part of a brigade commanded by Confederate General William "Grumble" Jones, were able to delay Kilpatrick for hours with one piece of artillery while a wagon train belonging to General Richard S. Ewell moved from the north into the pass.[63] Custer's men, fighting dismounted in the dark, were unable to clear the pass.[64]

At 3 am, Major Capehart and the 1st West Virginia Cavalry were ordered to assist Custer. When Capehart reported to Custer, he was ordered to make a charge. Kilpatrick sent his headquarters guard, Company A from the 1st Ohio Cavalry, to assist Capehart. In pouring rain and total darkness, the 1st West Virginia Cavalry charged down the mountain, capturing the Confederate artillery piece and an entire wagon train.[Note 11]

During the charge, flashes from a Confederate volley enabled the charging cavalry to find the exact position of its enemy. The fighting was hand-to-hand, but Capehart's cavalry was armed with sabers. The Confederate artillery piece was pushed down an embankment. The wagons became entangled in a massive traffic jam. Custer's men soon followed the West Virginians down the mountain. The captured wagon train consisted of 300 wagons and 15 ambulances, and the horses and mules pulling them. Soldiers captured totaled to 1,100 plus 200 officers. Casualties for the 1st West Virginia were only 2 killed and 2 wounded.[66] For this action, Capehart was later awarded the Medal of Honor.[67] He accomplished this while having a shattered ankle that was the result of being shot while fighting at Gettysburg.[68]

Following the battle at Monterey Pass, the division moved to Smithsburg (July 5), Hagerstown (July 6), and Boonsboro (July 7). Although Kilpatrick's division was attacked in Smithburg, Richmond's brigade was not involved in the fighting with the exception of its artillery. The brigade took the advance in the move to Hagerstown, and a portion of the 1st West Virginia was involved in the fighting. The regiment suffered 20 casualties fighting enemy infantry that was positioned inside of houses. The brigade camped for the night near Boonsboro, and was attacked on the next morning. After the enemy was driven away by Richmond's artillery, the 1st West Virginia made an unsuccessful pursuit.[69] On July 9, Colonel Othniel De Forest (who had been ill) of the 5th New York Cavalry reported for duty, and Richmond was relieved from command of the brigade. Richmond and the 1st West Virginia Cavalry reported to Frederick, Maryland, for provost duty. They remained there for a week while they arrested stragglers and formed a stragglers' camp.[70] Lee's army crossed the Potomac at Williamsport and Falling Waters on July 14.[71]

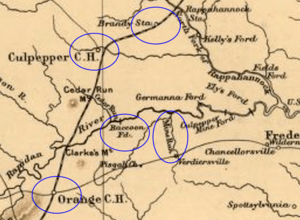

After the pursuit

For the last half of July, the regiment fought in some minor skirmishes, and eventually reported to Stafford, Virginia, near Fredericksburg.[70] On September 16, Colonel Richmond was injured from a fall of his horse at Raccoon Ford on the Rapidan River. He resigned in early November, and was discharged on a Surgeon's Certificate of Disability on the November 11.[72] During November, the regiment (ten companies) was in the Battle of Mine Run as part of Custer's Third Division. Their brigade commander was General Henry Eugene Davies, and the regiment was commanded by Major Harvey Farabee. Henry Capehart, the regiment's surgeon, was familiar with the territory, and provided valuable assistance to Davies in strategy and fighting—in addition to navigating the terrain.[16] Davies was impressed, and along with Kilpatrick and Custer recommended Capehart to replace the injured Colonel Richmond as commander of the 1st West Virginia Cavalry.[73] Capehart was commissioned as colonel on December 23, becoming the regiment’s commander.[20]

Army of West Virginia

Beginning in December, the regiment became part of the Department of West Virginia, but was unassigned.[2] Near the end of January 1864, the regiment returned to Wheeling. They stayed at Camp Willey on Wheeling Island for a few days before going to their homes for a 30 day furlough. About 500 men re-enlisted.[74] A reception to honor the regiment was held in Wheeling on February 3. The local newspaper called them "The Heroes of 70 Engagements".[75] The regiment left Wheeling during mid-March, departing on the B&O Railroad.[76] They became part of the 2nd Brigade, 2nd Cavalry Division, in the Army of West Virginia. They patrolled West Virginia for the next six weeks, but did not see any significant action.[2]

Beginning in May, the regiment was part of the 3rd Brigade, Second Cavalry Division. They participated in Averell's Raid on the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad, which was a valuable asset for the Confederacy because it enabled transportation of soldiers and supplies between the two states.[2] A salt mine and lead mine (for bullets) were located near the railroad line, and were also potential targets.[Note 12] On May 10, Averell's division (including the regiment) fought in the Battle of Cove Mountain in northern Wythe County, Virginia, while moving from its camp toward the railroad.[2] The 1st West Virginia Cavalry, with the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, twice led attacks at the mountain gap that was occupied by Confederate forces.[80] This battle was indecisive, although Confederate forces under the command of General William "Grumble" Jones, assisted by John Hunt Morgan's Raiders, prevented Averell's cavalry from moving through the gap.[81] Averell took a more difficult path through the mountains, and was eventually able to destroy 26 bridges and portions of railroad track near Dublin (New Bern), Virginia. Rainy weather made the mission difficult, and ruined some ammunition. The division was able to escape pursuing Confederate forces (and flooding rivers) and return to its base in West Virginia on May 18.[82]

On May 22, the regiment was fording the Greenbrier River just upriver from a waterfall. Their objective was to eliminate some Confederate sharpshooters that were harassing the cavalry. Colonel Henry Capehart stationed himself between the falls and the crossing. His standard procedure was to position himself down river at crossings, which would enable him to rescue men having trouble crossing the water. He was an expert rider and had a horse that was a good swimmer. In this circumstance, a private from Company B was swept out of his saddle while attempting to cross a swollen river with a swift current. Not only was the private swept over the falls, but Capehart and his horse were too. Capehart was able to rescue the private while both were being shot at by enemy sharpshooters.[83] On February 12, 1895, Capehart was awarded the Medal of Honor for this action. His citation read "Saved, under fire, the life of a drowning soldier."[84]

Hunter's Lynchburg Campaign

During early June, various Union forces met in Stanton, Virginia, and were resupplied. After a reorganization on June 9, General Duffié was assigned command of the First Cavalry Division, and General Averell command of the Second. The 3rd Brigade of the Second Cavalry Division was commanded by Colonel William H. Powell, and it consisted of the 1st and 2nd West Virginia Cavalry regiments. The infantry was led by General Crook. General David Hunter was the commander of the entire cavalry and infantry force.[85] On June 10, they moved toward Lexington, Virginia (Duffié's division took a different route), as part of a plan to capture Lynchburg. The force arrived in Lexington on June 11, and occupied the town for several days.[85] On June 14, Powell's brigade was sent forward to Liberty (today, Liberty is named Bedford), and drove away Confederate cavalry. During this time, Confederate reinforcements were arriving at Lynchburg.[86]

On June 16, the entire Union force left Liberty and approached Lynchburg from the southwest. Confederate soldiers under the command of General Jubal Early arrived in Lynchburg by train on June 17. The Battle of Lynchburg was fought on June 17 and 18. Approximately 44,000 soldiers participated in this Confederate victory.[87] The Union force could not capture Lynchburg, and was forced to retreat as supplies dwindled. Powell's brigade briefly became cut off from the rest of the army when he was not immediately notified of the retreat. The retreat was westward toward Charleston, West Virginia, because a northern retreat had too many obstacles. Powell's cavalry reached Union lines near New London as the Confederate army was close to catching them.[88] The retreat continued with the Confederate army in pursuit and various skirmishes along the way. Hunter's force reached Charleston on July 1. Losses for the entire force were 940 men.[89]

Shenandoah Valley

During July, the 1st West Virginia Cavalry left Charleston, West Virginia, for Parkersburg—where they boarded the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad with their horses to begin a three-day trip to the other side of the state. Their destination was the rail station at Martinsburg.[90] The regiment was commanded by Colonel Henry Capehart, and was part of the 2nd Brigade, 2nd Cavalry Division, Army of West Virginia.[Note 13] The Army was commanded by General Hunter. The Second Cavalry Division was commanded by General Averell, and the 2nd Brigade of the Second Division was commanded by Colonel Powell.[92]

Battle of Rutherford's Farm

The Battle of Rutherford's Farm, also known as the Battle of Carter's Farm, occurred on July 20, about 4 miles (6.4 km) north of Winchester, Virginia.[93] While portions of Hunter's army were still arriving at the Martinsburg area, Union General Hunter sent General Averell from the Martinsburg toward Winchester to meet a perceived threat to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad from Early's Army of the Valley.[94] Averell did not have his entire cavalry force when he started, but had about 1,000 men from the 1st and 3rd West Virginia Cavalries. He also had another 1,350 men from infantries.[95] He advanced southwest down the Winchester and Martinsburg portion of the Valley Turnpike, with the 1st West Virginia Cavalry on his left (east), infantry in the middle, and the 3rd West Virginia Cavalry on his right (west).[96]

Averell was attacked, north of Winchester between the Carter and Rutherford farms, by Confederate troops under the command of General Stephen Dodson Ramseur. Ramseur's division had been ordered to assume a defensive position at Winchester, which would enable the main portion of Early's army to safely withdraw south from Berryville and Winchester. Early had no plan to attack the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad—it was more important for it to appear that he would attack it.[97] Against orders, Ramseur attacked Averell's smaller force.[98] The Confederate attack initially appeared successful, as the 3rd West Virginia on the west side was stymied, and the 1st West Virginia on the east side was forced to retreat from cavalry led by Mudwall Jackson.[99] However, Averell was reinforced by 300 men from the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry who had arrived at Martinsburg after Averell had departed.[95] The unexpected reinforcement led to a Confederate panic, and Averell won the battle.[100] The Confederate loss was about 400 to 450 men, and Averell's men collected 500 rifles from the battlefield. Averell's casualties were about 220.[101] The retreating rebels were not pursued because Averell was unsure if the rest of Confederate General Early's army was nearby, so the Confederates were still able to evacuate Winchester (including a hospital) and retreat further south.[102]

Battle of Kernstown II

After Averell's victory at Rutherford's Farm, he was joined by another cavalry division and infantry. General George Crook commanded the entire force. Both cavalry divisions sent men on scouts to find Early's army. Crook believed that most of Early's army had left the valley to defend the Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia. He did not believe the reports of Averell and General Duffié (commander of the First Cavalry Division) that said enemy infantry, artillery, and cavalry were in the area.[103] Crook was mistaken, and both cavalry units made accurate reports.[104]

On July 24, Averell was ordered to conduct a flanking maneuver near Front Royal to cut off what Crook believed was a small band of Confederates. Averell encountered a much larger enemy force than he was led to expect, and the Second Battle of Kernstown began. As portions of Crook's force began retreating north through Winchester, he finally understood the situation.[105] He organized a more orderly retreat.[Note 14] Powell's brigade (including the 1st West Virginia Cavalry) and an infantry brigade led by Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes (future President of the United States) were among the few organized units remaining.[108] They became the rear guard against the pursuing Confederate cavalry.[109]

The Confederates continued their pursuit on July 25. However, all soldiers were soaked in cold hard rain, and by now were hungry and thirsty. An ambush by Hayes' men brought the Confederate pursuit to a halt.[110] Powell's cavalry brigade was used to drive the Confederates back.[109] Crook was ordered to retreat north across the Potomac River, and the Confederates reoccupied Martinsburg (in addition to controlling Winchester). Most of Averell's division camped at Hagerstown, Maryland.[111] The 1st West Virginia Cavalry lost a total of 28 men killed, wounded, missing, or captured.[112]

Chambersburg and Moorefield

The regiment was part of a cavalry force commanded by General Averell that pursued Confederate Generals McCausland and Bradley Johnson after the rebels burned the Pennsylvania community of Chambersburg.[113] After multiple skirmishes and Confederate threats to burn more towns, McCausland's two brigades of cavalry were caught in Moorefield, West Virginia. In a surprise attack at dawn on August 6, 1864, Averell captured over 400 Confederates.[114] In this battle, brigade commander Colonel William H. Powell rode with Colonel Capehart and the 1st West Virginia Cavalry. After the 3rd West Virginia Cavalry charged across the South Branch of the Potomac River and met strong resistance from the Confederate 17th Virginia Cavalry, they were reinforced by the 1st West Virginia—and the two regiments overwhelmed the Confederates.[115] Powell's report said "The thanks of the brigade are also due to the First West Virginia Cavalry for the timely support given to the Third West Virginia Cavalry at a time when the enemy seemed conscious of our weakness, and attempted to rally their forces and to repel the advance of our lines, and for its joint operation with the Third Virginia Cavalry, driving the enemy into the mountains for a distance of twelve miles, killing, wounding and capturing many, also capturing one battle-flag and two pieces of artillery."[116]

Thus, Averell achieved the only two major Union victories during the summer in the Shenandoah Valley. In both cases, Averell was operating alone in command.[117] In this case, Early's cavalry was never again the superior force it once was. Despite Averell's successes, General Philip H. Sheridan assumed command of all Union troops in the Shenandoah Valley on August 7. Hunter asked to be relieved.[117]

Battle of Opequon

The Battle of Opequon, also known as the Third Battle of Winchester, began in the morning on September 19, 1864.[118] Some historians consider this the most important battle of the Shenandoah Campaign. Philip Sheridan's Army of the Shenandoah defeated Jubal Early's Army of the Valley. Union casualties were about 5,000 out of 40,000 men, while Confederate casualties were about 3,600 out of 12,000 men. Generals and colonels on both sides were killed, including Confederate Colonel George S. Patton Sr.—grandfather of the famous World War II tank commander, General George S. Patton. Confederate General Robert E. Rodes was killed, and Confederate cavalry generals Fitzhugh Lee and Bradley Johnson were among the wounded. General David Allen Russell, killed in action, was among the Union casualties.[119] The majority of the Union casualties were in the infantry. Averell's 2nd Cavalry Division had only 35 casualties, including four from the 1st West Virginia Cavalry.[120]

Battle of Fisher's Hill

This battle occurred on September 21–22, 1864.[121] General Sheridan considered this battle a continuation of the Battle of Opequon near Winchester. General Early's Confederate army was pursued from Winchester to Fisher's Hill, where the rebels had strong fortifications and an advantageous location given the terrain.[122] Using a night march and diversions by other segments of the army, General Crook secretly positioned his infantry to the rear of the Confederate line. Averell's cavalry division (which included the 1st West Virginia Cavalry as part of Powell's 2nd Brigade), plus a division of infantry led by General James B. Ricketts, created the diversion that enabled Crook's two infantry divisions to remain concealed while they positioned themselves near Little North Mountain. Crook's fighters, who were experienced in fighting in mountainous terrain, flanked the west side of the Confederate line. Crook's surprise attack broke through the Confederate lines, and was the major reason for the Union victory. Powell's cavalry brigade pushed through the gap created by Crook, and chased rebels as they fled south. The chase continued throughout the evening.[122]

After the battle, Sheridan pressured his officers to pursue Early's retreating army. On September 23, Sheridan became impatient with the cautious commander of the Second Cavalry Division, General Averell. Sheridan replaced Averell with one of his brigade commanders, Colonel William H. Powell.[122] Powell was promoted to brigadier general shortly afterwards.[123] Colonel Henry Capehart was designated commander of Powell's old brigade, and Capehart's brother, Charles, became commander of Capehart's 1st West Virginia Cavalry regiment. Powell's 2nd Cavalry Division pursued Early further south.[124]

Battle of Cedar Creek

.jpg)

The Battle of Cedar Creek occurred on October 19, 1864. Jubal Early's Confederate Army appeared to have a victory until General Sheridan rallied his troops to a successful counterattack. Although Union casualties were more than double those of the Confederates, this battle is considered a Union victory, and Confederate troops were driven from the battlefield. The Union troops recaptured all of their artillery lost earlier in the battle, and 22 additional cannons belonging to Early's army.[125] Union cavalry were commanded by General Alfred Torbert. The 1st West Virginia Cavalry remained in Powell's Second Division, 2nd Brigade. Powell positioned his division near Front Royal to prevent Confederate cavalry under General Lunsford L. Lomax from flanking the Union force.[126] The 1st West Virginia Cavalry had a total of 3 casualties in this battle.[127]

Nineveh

On November 12, the Second Division again fought Lomax's Cavalry.[128] General William H. Powell, commander of the division, sent most of his 1st Brigade out beyond Front Royal, where it encountered a portion of Lomax's cavalry commanded by General John McCausland. The Confederates slowly pushed the 1st Brigade back. Powell brought his 2nd Brigade (Capehart's, including the 1st West Virginia Cavalry) to the front while the 1st Brigade moved to the rear.[129] Capehart's brigade charged, resulting in a short clash that ended with the Confederates retreating as fast as they could. They were chased for 8 mi (12.9 km).[130] Powell captured all of the rebel artillery (two guns), their ammunition train, and took 180 prisoners.[131] Newspaper accounts said McCausland was slightly wounded.[132] Two men from the 1st West Virginia Cavalry were awarded the Medal of Honor for actions in this battle. Private James F. Adams, from Company D, received his medal for "Capture of State flag of 14th Virginia Cavalry (C.S.A.)".[133] The other medal winner was Sergeant Levi Shoemaker from Company A. His citation is "Capture of flag of 22d Virginia Cavalry (C.S.A.)".[134]

Third Division

Powell resigned from the Union Army on January 5, 1865.[135] His father had died and his mother was seriously ill.[136] Sheridan reorganized his 8,000-man force into two cavalry divisions.[137] General Wesley Merritt was Sheridan's cavalry commander. General Thomas Devin led the First Division, and the Third Division was commanded by General George Armstrong Custer. There was no Second Division.[138] The 1st West Virginia Cavalry became part of the 3rd Brigade, Third Division Cavalry Corps. The brigade consisted of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd West Virginia Cavalry regiments, and the 1st New York (Lincoln) Cavalry, and was commanded by Colonel Henry Capehart.[139] These four regiments had been most of the force, commanded by General Averell, that had a major victory at Moorefield during August 1864. As a brigade, they had also performed extremely well three months later at Nineveh under the command of General Powell. The brigade became known as Capehart's Fighting Brigade, after its skills were noticed by Sheridan—who called it "the fighting brigade".[140] Both divisions spent about six weeks in winter quarters, where they rested and were given fresh clothing. On February 27, they left Winchester and moved south. Their purpose was to eliminate Jubal Early's Confederate army.[141]

Laurel Brigade

In late February, General Early received additional troops which were supposed to enable him to attack instead of flee. The reinforcement was the elite Confederate cavalry known as the Laurel Brigade, and it was under the command of General Thomas L. Rosser.[142] Many of the men in the proud and well–equipped Laurel Brigade had served with General Jeb Stuart—the Confederacy's most famous cavalry officer.[Note 15] Early added his own cavalry to Rosser's command, and sent them toward Custer's approaching division.[142] Rosser filled a covered bridge with rails on the middle fork of the Shenandoah River, and this is where he planned to confront Custer.[144]

At 2:00 am, on March 1, Capehart's brigade was awakened and told to prepare to move without breakfast or feed for their horses. Their objective was to remove the obstacle of Rosser's cavalry, which would enable the rest of Custer's division to attack Early's army—which was thought to be between Harrisonburg and Staunton.[144] At the covered bridge, Capehart sent a portion of his brigade, dismounted, to attack Rosser. The 1st West Virginia cavalry was sent upriver where it crossed and then charged down on Rosser.[Note 16] The brigade chased Rosser's cavalry from the area, captured 50 men, and captured all of Rosser's artillery.[146] Thus Custer, utilizing Capehart's brigade (including the 1st West Virginia Cavalry), defeated one of the Confederacy's best cavalries.[147]

Battle of Waynesboro

Two federal cavalry divisions encountered the remnants of General Early's army at Waynesboro, Virginia, on March 2. Most of Early's army was killed or captured, although Early evaded capture.[148] Custer's division did the fighting. His 1st Brigade dismounted and attacked as infantry, then the 3rd Brigade (Capehart's brigade including the 1st West Virginia Cavalry) charged and cut off over half of Early's force—which forced that portion of the rebels to surrender. All of Early's headquarters equipment was captured, as were 11 pieces of artillery.[135] Capehart's brigade chased the fleeing rebels toward Rockfish Gap.[149] A New York newspaper credited the 3rd Brigade with capturing 5 pieces of artillery, 67 wagons of ammunition and food, and 1 battle flag.[150] Early's army was eliminated from the war.[151]

Sheridan leaves the Valley to fight Lee's army

Sheridan's original orders were to destroy the Virginia Central Railroad and then meet with the army of Union General William Tecumseh Sherman in North Carolina.[152] Sheridan reached Charlottesville on March 3, but faced delays caused by muddy roads.[153] On March 5, Sergeant Richard Boury, from Company C, was part of a squadron of the 1st West Virginia Cavalry sent into the mountains to find some rebels that had retreated from Waynesboro. Boury captured a flag and three rebels.[154] He received the Medal of Honor, and the citation described his action as being "at Charlottesville" .[155]

Over the next few days, Custer's division (including the 1st West Virginia Cavalry) destroyed the railroad line between Lynchburg and Amherst Courthouse, and Devin's division destroyed the James River Canal. Rainy weather had caused the James River to swell. The deeper and wider river became dangerous to cross, and fords became unusable. The swollen river, and bridges that had been destroyed by the Confederates, persuaded Sheridan to move east toward the Confederate capital city of Richmond instead of moving south across the river to link with Sherman's army in North Carolina. Sheridan's army kept north of the James River, and reached Columbia, Virginia, on March 10.[153]

Private Archibald H. Rowand, Jr., of the 1st West Virginia Cavalry's Company K, was a scout and spy. During March, he was one of two men who were able to get through Confederate lines to deliver a message from General Sheridan to General Grant. To accomplish this feat, Rowland wore a Confederate uniform for much of his journey. His 48-hour journey covered 145 mi (233.4 km) on horseback and an additional 11 mi (17.7 km) on foot. Near the end of his journey, he was chased by Confederates and had to abandon his horse and swim the Chickahominy River. That started the walking portion of his journey. He was wet, muddy, and was wearing only his underclothing when he crossed into Union lines.[Note 17]

Sheridan's two cavalry divisions continued their movement eastward, still staying north of the swollen James River. Both divisions reached a Union Army base at the river port community of White House, Virginia (not to be confused with the "White House" in Washington, D.C.), on March 18, 1865.[158] At White House, the two divisions were resupplied, and rested for five days.[158]

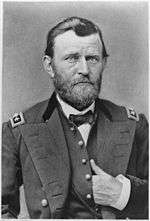

Sheridan's force departed from White House on March 24, and met the Army of the Potomac near Petersburg on March 27.[158] The Army of the Potomac was "the Union's primary army operating in the East."[159] It often confronted Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, and was tasked with protecting the capital in Washington, D.C., while attempting to capture the Confederate capital city of Richmond. Sheridan's Army of the Shenandoah was still considered separate from the Army of the Potomac, so he received orders directly from General Ulysses S. Grant (the Union's highest-ranking officer and future president of the United States). Grant was working on site with General George Meade, the commander of the Army of the Potomac.[159] Meade had partially surrounded Lee's army at Richmond and Petersburg, but Lee still had a western escape route. Grant ordered Sheridan to proceed to Dinwiddie, Virginia. The two divisions were joined by the Second Cavalry Division from the Army of the Potomac, which was led by General Crook.[160] The three cavalry divisions totaled to a force of about 9,000.[161] Since Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was concentrated in Richmond and Petersburg, Sheridan's movement would flank Lee's army—and threaten Lee's escape route if he decided to abandon Richmond and Petersburg.[162]

Battle of Dinwiddie Court House

Sheridan's army reached Dinwiddie Court House on March 29. His first two divisions went into camp at that location, while Custer's Third Division (which included the 1st West Virginia Cavalry regiment) guarded the wagon trains further back at Malone's Crossing.[161] The Third Division's 3rd Brigade consisted of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd West Virginia cavalry regiments and included the 1st, 2nd, and the 1st New York (Lincoln) Cavalry.[160] On the next day, Devin's First Cavalry Division, and a brigade from Crook's Second Division, were sent north toward Five Forks. Their reconnaissance found a strong enemy force led by General George E. Pickett, and the Union cavalry was driven back.[163]

The Battle of Dinwiddie Court House occurred on March 31, and is considered a Confederate victory.[164] The same Union force that was driven back earlier was again sent toward Five Forks. The remaining portion of Crook's Second Division met the Confederates further west at Chamberlain's Creek. During this time, infantry under the command of Union General Gouverneur Kemble Warren, located east of Sheridan's army, was driven back. The attacking Confederate force then turned its attention to Sheridan—Sheridan's cavalry had to face two enemy infantry divisions and a cavalry.[165]

As the Union cavalry was driven back toward Dinwiddie Court House, Capehart's 3rd Brigade was recalled from duty guarding the wagon train. They moved near what would soon become the front, an open area in front of Dinwiddie. Capehart's brigade, sometimes called the "Virginia Brigade", used rails from a fence to quickly build a protective area for fighting while dismounted. The brigade was able to halt the Confederate attack in fighting that continued until after dark.[166]

Battle of Five Forks

The Battle of Five Forks occurred on April 1, 1865. Five Forks is a small community in Dinwiddie County, located between Dinwiddie Court House and Petersburg. For this Union victory, Sheridan received reinforcements from the Fifth Corps and a division of cavalry from the Army of the James.[167] Sheridan's plan was to capture the Confederate infantry that had isolated itself beyond the Confederate line of defense after pursuing Sheridan at Dinwiddie.[168]

Union infantry attacked from the east side of the battlefield, while most of the cavalry attacked from the south and west. Capehart's brigade attacked from the southwest, and eventually was on the extreme western side of the battlefield. At times, the cavalry fought dismounted, with their horses led at a safe distance behind. The opposing forces were always within range of the Union cavalry carbines, keeping the weapon's seven-shot advantage—and not enabling the Confederate infantry to utilize the advantage of their longer range weapons.[169] After 5:00 pm, Custer's division (including Capehart's brigade) remounted, and attacked a Confederate battery. The battery was unable to shoot low enough to hit the charging cavalry, and was soon captured. The rebels responded with a Rebel yell, and soon the opposing forces were fighting in close combat using sabers.[170]

A portion of Capehart's brigade drove the rebels to the end of the field, only to be partially driven back by a second group of Confederate cavalrymen. After the regiment was reinforced by the rest of Capehart's brigade, the Confederates were driven from the area, and numerous battle flags were captured.[171] Lieutenant Wilmon W. Blackmar, from Company H of the 1st West Virginia cavalry, was awarded the Medal of Honor for extraordinary heroism in this battle. At the time, he was brigade provost-marshal on the staff of Colonel Henry Capehart. The brigade had been ordered to join a charge against what appeared to be a main body of the enemy. After the pursuit began, Blackmar observed that the brigade was chasing a small detachment of Confederates, and the main body of the Confederates was about to isolate the cavalry from the Union infantry. Blackmar caught up with Capehart and informed him of the situation, and was ordered to reform the brigade in the correct line of battle. Blackmar reformed a portion of the brigade and led a charge (without waiting for the rest of the brigade). The charging men took prisoners, and captured artillery, wagons, and ambulances. Custer and Capehart promoted Blackmar to captain immediately.[172] Blackmar's Medal of Honor citation says "At a critical stage of the battle, without orders, led a successful advance upon the enemy." [173]

Although the battle is considered finished on the day it started, skirmishing continued as Lee's army tried to escape to the west. On April 2, Capehart's brigade attacked the Confederates at Namozine Church. In this confrontation, Capehart's horse was killed, and Capehart had his clothing pierced with several shots that did not seriously wound him.[174] On the next day, another brigade from Custer's division attacked, and eventually the Confederates escaped toward Amelia Court House. This inconclusive battle, described as a Confederate rear guard action, became known as the Battle of Namozine Church. Total casualties for both sides are an estimated 75, and Confederate General Rufus Barringer was captured.[175]

Battle of Sailor's Creek

On April 1, General Lee, realizing the threat to his army and the Confederate government in Richmond, recommended abandoning the city. Confederate president Jefferson Davis left the city on April 2. Lee's army began moving west a few days later.[162] On April 6, Union troops chased Lee's Army to an area south of the Appomattox River near Saylor's Creek. The area was about halfway between Richmond and Lynchburg. Some historians say the Battle of Sailor's Creek was actually three battles that were fought simultaneously at Lockett Farm, Hillsman Farm, and Marshall's Crossroads.[176] Sheridan's cavalry fought in the Marshall's Crossroads area. Confederate General Richard Ewell's two divisions were between Little Sailor's (also spelled Saylor's and Sayler's) Creek and Marshall's Crossroads. Confederate General Richard H. Anderson commanded additional divisions mostly west of Marshall's Crossroads. Sheridan's cavalry, commanded by General Merritt, was on the southeast side, with the three divisions commanded by Devin, Crook, and Custer. The 1st West Virginia Cavalry, as part of Capehart's brigade and Custer's Third Division, began their fight south of Marshall's Crossroads. Once again, Union infantry attacked from the east, while Sheridan's cavalry attacked mostly from the south and west.[177] Sergeant Francis M. Cunningham, from Company H of the 1st West Virginia Cavalry, wrote that the battle "was one of the hardest cavalry fights of the war."[178] Custer's cavalry division made numerous charges upon the Confederate lines. Although the charges were successful in capturing artillery and men, casualties were high. Armies on both sides had already suffered numerous casualties in battles at Dinwiddie Court House and Five Forks. In the case of Company H, only four men remained for the final charge.[178]

As Colonel Capehart (commander of Custer's 3rd Brigade) reviewed the Confederate army's position, General Custer rode along the lines in plain view of the Confederate infantry, taunting his enemy with captured Confederate battle flags. The Confederates responded by taking numerous shots at the general, hitting his horse. Custer dismounted without injury. Capehart realized that the Confederates would need time to reload their single-shot rifles, and requested that his 3rd Brigade attack immediately. Custer quickly agreed, and Capehart's brigade of about 1,400 cavalry men (including the 1st West Virginia) charged the Confederate lines.[179] In addition to the 1st West Virginia Cavalry, Capehart's 3rd brigade still included the 2nd and 3rd West Virginia Cavalries—plus the 1st New York (Lincoln) Cavalry.[160]

Capehart and Lieutenant Colonel James Allen of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry led the charge. The men used sabers, carbines, and revolvers to move through three Confederate infantry lines. A large portion of Ewell's corps became surrounded, causing many of the demoralized Confederate soldiers to surrender. Thus, the Union troops captured more than 20 percent of Lee's army. Approximately 8,000 Confederate soldiers, including eight generals, were killed or captured.[179] Among the surrendering generals was the corps commander Richard Ewell. Another general captured was Custis Lee, eldest son of the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee. Upon seeing the battered survivors from his army, Robert E. Lee said "My God, has the army dissolved?" Although many of Anderson's men escaped westward, the battle is considered the "death knell" for Lee's Confederate Army.[180] The Battle of Sailor's Creek is the last major battle of the American Civil War.[176]

Five men from the 1st West Virginia Cavalry were awarded the Medal of Honor for actions in this battle. Captain Hugh P. Boon received his medal for capturing a flag.[181] Boon's Company B was part of a charge when he noticed a battalion of enemy infantry on the right. He led his company away from the original charge, moving toward the infantry. His company routed the Confederate battalion, and Boon captured the flag of the 10th Georgia Infantry. Although Boon was worried that he did not exactly follow orders, a superior officer witnessed the affair and acknowledged that the captain took appropriate action.[182] Sergeant Francis M. Cunningham's Medal of Honor citation reads "Capture of battle flag of 12th Virginia Infantry (C.S.A.) in hand-to-hand battle while wounded."[183] Cunningham's horse had been killed, but he found a Confederate mule that leaped a Confederate breastworks when the regiment made a charge. Although Cunningham, who was from Company H, was shot twice (but survived), he captured a Confederate flag using his saber. General Custer later recommended Cunningham for the award.[184] Commissary Sergeant William Houlton won his medal for the capture of a flag, but the regiment was not identified in the citation.[185] Corporal Emisire Shahan from Company A received his medal for "Capture of flag of 76th Georgia Infantry (C.S.A.)".[186] The citation for Medal of Honor winner Private Daniel A. Woods, who was from Company K, says "Capture of flag of 18th Florida Infantry (C.S.A.)".[187]

Battle of Appomattox Station

On April 8, Lee's Army of Northern Virginia continued to flee westward. Two Union army corps were following. Additional Union troops, including cavalry led by General Sheridan, were further west. Sheridan hoped to block Lee's retreat. His advance force was Custer's Third Division. The advance portion of Lee's army consisted of artillerymen led by General R. Lindsey Walker, and they passed through the small community of Appomattox Court House toward their destination—Appomattox Station. Walker's artillery force led a wagon train with luggage and ambulances. Three trains, sent from Lynchburg, were waiting at Appomattox Station with supplies. They were guarded by a small cavalry brigade.[188]

Custer learned that the Confederate supply trains were waiting at Appomattox Station. He sent the 2nd New York Cavalry forward, and the supply trains were captured. A few pieces of track were removed to prevent the trains from going back to Lynchburg. Walker was surprised to see Union troops waiting at the station, and set up his artillery. He was forced to form a battle line in a wooded area—not an ideal situation for his weaponry. He was able to repel Custer's 1st Brigade.[188]

Custer used his 2nd and 3rd (Capehart's) brigades for two more ineffective attacks. Finally, Custer made a rare night attack using his entire division.[Note 18] The 1st West Virginia Cavalry was on Custer's extreme left.[190] Strong moonlight reduced the risk of getting lost or misidentifying friendly and enemy soldiers. The night attack was successful, and Custer's division captured 24 to 30 artillery pieces. About 1,000 Confederates were taken prisoner, and 150 to 200 wagons were captured.[188]

Two men from the 1st West Virginia Cavalry were awarded the Medal of Honor for actions in this battle. Corporal Thomas Anderson, from Company I, received his medal for capturing a Confederate flag.[191] The flag has been, at times, displayed in Lee Chapel and Museum of Washington and Lee University.[Note 19] Charles Schorn, Chief Bugler from Company M, also received the Medal of Honor for actions in this battle after he captured the flag of the Sumter Flying Artillery.[193] This flag, which had been carried by the Sumpter Flying Artillery since 1861, was captured in Custer's final nighttime charge.[190]

Battle of Appomattox Courthouse

_(14593729959).jpg)

On April 9, Lee's Army of Northern Virginia continued to flee westward. Infantry led by Generals John Brown Gordon and James Longstreet, and cavalry led by Fitzhugh Lee formed a battle line near the Appomattox Court House. This was their last chance to escape to Lynchburg, as Union troops were attempting to surround them.[194]

A Confederate officer approached Capehart's 3rd Brigade on horseback under a flag of truce. Capehart and the officer rode down the column to General Custer, where the officer told the general that Lee and Grant were in correspondence concerning a surrender of Lee's Army.[Note 20] The Confederate officer also requested a truce until the results of the negotiation were known.[195] Custer's response was "Tell General Longstreet that I am not in command of all the forces here, but that I am on his flank and rear with a large cavalry force, and that I will accept nothing but unconditional surrender."[195]

The 1st West Virginia Cavalry's participation in this "battle" was mostly preparing to attack—but no full-fledged charges were made. Shortly after his meeting with Longstreet's representative, Custer turned command of the division over to Colonel Henry Capehart, commander of the 3rd Brigade (that included the 1st West Virginia Cavalry). Custer rode off to see General Sheridan.[195]

Thus, on April 9, 1865, Confederate General Lee unconditionally surrendered his starving Army of Northern Virginia to General Grant. The surrender look place at the home of Wilmer and Virginia McLean in the small community of Appomattox Court House, Virginia.[197]

War's end

The 1st West Virginia Volunteer Cavalry remained in battle line until the evening of April 9, and then went into camp. On the next day, they marched toward Burkesville Junction, arriving on April 12. After resting for the night, they marched to Nottoway Court House, and received new clothing. The cavalry reached Petersburg, Virginia, by April 18, and camped outside the city.[198] On the same day, Custer sent a recommendation to Secretary of War Stanton that Colonel Henry Capehart be promoted to Brigadier General, retroactive to March 1.[Note 21] On April 24, the division started a march to North Carolina to join General William Tecumseh Sherman's army confronting the Confederate army of General Joseph E. Johnston. They reached South Boston, on the Dan River in Virginia, which is close to the North Carolina border. However, on April 28, they became aware that Johnston had surrendered. On the next day, the division began its return north.[200]

The northbound division reached Petersburg on May 5, where they rested. They were visited by General Custer's wife, Elizabeth Bacon Custer. Knowing that her husband's division would soon be marching in Washington to celebrate the Union victory, Mrs. Custer suggested that the entire division wear a red tie like her husband's while it was on parade. On May 10, the division began the trip to Washington, and eventually reached Alexandria, Virginia, where they made camp.[201]

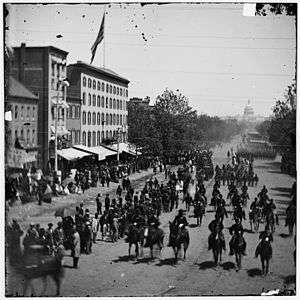

Grand Review of the armies

The Grand Review of the Armies began on May 23, 1865, as a Union celebration of the end of the Civil War. Union troops paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC. The parade was led by Custer's 3rd Division.[202] The division was led by Capehart's brigade.[203] The New York Times described men in Custer's division as "being decorated with a scarf or tie, known as the Custer Tie, red in color ..." It also said "Capehart's brigade of West Virginia Veterans, as trusty a body as ever drew a sabre, are singled out for their fine appearance ..."[204]

France

Capehart resigned after the grand review. He was replaced by Colonel A. W. Adams of the First New York Cavalry. At the time, France had occupied Mexico, and the United States selected some of its best cavalry regiments to fortify the Texas-Mexico border in case of trouble. Capehart's Fighting Brigade was one of the cavalries selected. Its assignment was to report to Louisville, Kentucky, to prepare to March to Texas. While the majority of the brigade was proceeding to Louisville via railroad, the trouble with France ended—and all four of the brigade's regiments were ordered to muster out.[205]

Final muster out

In early June 1865, the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd West Virginia Cavalries were ordered to proceed to Wheeling, West Virginia, to muster out. On June 17, the men and their horses were loaded onto a Baltimore & Ohio Railroad train where they departed for Wheeling. The three regiments camped on Wheeling Island between Wheeling and Belmont County, Ohio.[206] They were officially mustered out on July 8, 1865. While Generals Crook and Custer would continue service with the federal cavalry in the western United States, the 1st West Virginia Volunteer Cavalry Regiment ceased to exist.[207] During the war, the regiment had 10 officers and 71 enlisted men killed. An additional 126 men died from disease.[2] At the end of the war, the regiment was part of the highly regarded Capehart's Fighting Brigade, and was one of the most active, and most effective, of the West Virginia regiments. Fourteen men received the Medal of Honor, the most for any West Virginia regiment.[1]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ McGee later transferred to the Third West Virginia Cavalry, where he eventually became its commander. John Lowry McGee was commissioned as major of the 3rd West Virginia Cavalry on March 25, 1862; lieutenant colonel on July 18, 1863; and colonel on March 10, 1865.[3] The National Park Service spells the name as J. Lowry McGee.[4] One author lists his name as John L. McGee.[5]

- ↑ George Washington Gilmore formed a company of cavalry independently at the request of General George B. McClellan, and Gilmore was its captain.[8] Gilmore's company was originally called the Pennsylvania Dragoons and was formed July 1861 with men from Fayette County, Pennsylvania.[9] An example of it fighting detached is the Wytheville Raid, where it fought with an additional company from the 1st West Virginia Cavalry, an infantry regiment, and another cavalry regiment.[10] Beginning July 14, 1863, Gilmore's Company served with the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry, and finished its service as Company L of that regiment.[11]

- ↑ The Ringgold Cavalry was an independent cavalry company from Pennsylvania that was formed in 1847. At the start of American Civil War, its captain was John Keys, and its first lieutenant was Henry Annisansel.[13] On September 6, 1861, Annisansel left to become colonel of the First Virginia Cavalry.[14]

- ↑ Examples of men commanding detachments of the 1st West Virginia Cavalry during 1862 are: Major Benjamin F. Chamberlain commanded six companies at the First Battle of Kernstown;[17] Captain Isaac P. Kerr commanded a small detachment at the Battle of Cedar Mountain;[18] and Major John S. Krepps commanded 3 companies at Second Bull Run;[19] Major Joseph Darr, Jr. was commissioned as a major in the regiment on September 25, 1861, and was promoted to lieutenant colonel effective June 16, 1863.[20] However, Darr was normally stationed in Wheeling instead of in the field, and was a chief mustering officer in 1864.[21]

- ↑ From January to March, 1862, the 1st (West) Virginia Cavalry was part of Lander's Division in the Army of the Potomac. For a portion of the year, four companies were assigned to General Robert H. Milroy, while eight companies were assigned to General Shields and then General John Buford. Buford and Milroy had commands in the Army of Virginia.[2]

- ↑ General Frederick Lander brought court martial charges against the 1st (West) Virginia Cavalry's Colonel Anisansel for "failing to obey an order to charge the enemy" at Bloomery Gap.[1] Colonel Richmond of the 1st (West) Virginia Cavalry was arrested for refusing to follow an order on December 31, 1862.[27]

- ↑ Mosby estimated that he had 70 to 80 men.[38] Union General Julius Stahel described the Confederate force as Mosby's guerrillas with the "Black Horse Cavalry and a portion of a North Carolina regiment".[39] (The Confederate Black Horse Cavalry was founded in the Warrenton area of Virginia.)[40] Major Benjamin F. Chamberlain's report, which listed him (Chamberlain not Krepps) as commanding the First (West) Virginia Cavalry, said they were "attacked by about 1,000 rebel cavalry."[41]

- ↑ Union General J.J. Abercrombie's report said that Mosby's "front rank was dressed in the uniform of United States soldiers".[41] A newspaper article stated that Mosby's men were mistaken for the First Vermont Cavalry.[43] However, Union Sergeant Haven described the enemy as having "no regularity of uniforms being clad in everything they could find".[44] Another source believed the Union leaders covered for the regiment, writing that in "an effort to excuse lax security, they later reported that the front rank of Rangers were dressed in Union uniforms."[38]

- ↑ Company I and Gilmore's Company participated in the Wytheville Raid during mid-July 1863. Both suffered severe casualties—about one third of their men. Company I's Captain Dennis Delaney was killed, and both his lieutenants severely wounded. First Lieutenant William E. Guseman died from his wounds, while Second Lieutenant Charles H. Livingstone was taken prisoner.[47]

- ↑ Charles Capehart was an officer in two Illinois infantry regiments before joining the 1st (West) Virginia Cavalry as a captain on July 2, 1862.[58] He was commissioned as major of the regiment on June 6, 1863.[20]

- ↑ One source says 640 officers and men made the charge.[64] Another source said that less than 100 men followed through with the charge.[65]

- ↑ The salt mine and lead mine targets are listed by Private Joseph Sutton, who participated in the raid, in his book.[77] The salt mine was located west of Wytheville at a community named Saltville. The lead mine was located a few miles south of Wytheville and about 25 mi (40.2 km) west of the Dublin railroad depot which was a regional headquarters for the Confederate Army.[78] The Dublin Depot was originally named Newbern Depot, although the town of Newbern is 2 mi (3.2 km) south of the railroad line. A short time before the Civil War, the depot was renamed Dublin Depot in honor of the New Dublin Presbyterian Church, which was located nearby. Thus, some maps from the early 1860s still used New Bern (or Newbern) to identify the depot.[79]

- ↑ General George Crook called this army the "Army of the Kanawha".[91] The U.S. National Park Service calls the army the "Army of West Virginia.[2]

- ↑ The retreat was initially very disorganized. One brigade commander from Duffié's First Division caused panic by ordering teamsters to bring their horses to a trot as his brigade fled north.[106] The main road eventually became littered with burning wagons. Duffié's other brigade, led by Colonel William B. Tibbits, performed much more admirably. His brigade made several charges that enabled trapped infantry men to escape.[107]

- ↑ Jeb Stuart was one of the Confederacy's most famous leaders. One historian wrote "Few Confederate generals achieved wider renown during the Civil War than Major General James Ewell Brown Stuart."[143] He was killed in battle during mid-May 1864.[143]

- ↑ A member of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry wrote that Capehart (the brigade's commander) sent the 1st West Virginia upriver.[144] A member of the 1st New York Cavalry wrote that Custer (the division commander) sent the 1st New York Cavalry, supported by the 1st West Virginia Cavalry, upriver.[145]

- ↑ Rowand's adventure was discussed in a Pittsburg newspaper article in 1998.[156] West Virginia University has a picture of Union spy Rowland in a Confederate uniform on its web site.[157]

- ↑ Night attacks were rare during the American Civil War because there was too much of a chance of a friendly fire incident. The darkness made it difficult to determine friend or foe.[189]

- ↑ The Lee Chapel and Museum at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia, has displayed various flags from the American Civil War. Among those flags, identified as Battle Flag no. 356, is the Confederate flag captured by Corporal Thomas Anderson of the 1st West Virginia Cavalry.[192]

- ↑ One author (Lang) says the Confederate approached General Henry Capehart.[195] A second author (Sutton) says the Confederate officer approached "Colonel Briggs, of the seventh Michigan".[196]

- ↑ Capehart's retroactive promotion can cause confusion. Custer's April 18 recommendation was a promotion retroactive to March 1.[199] This meant that during battles such as Five Forks and Sailor's Creek, Capehart was a colonel, but after April he was considered a general since before those and several other battles. Capehart was breveted to brigadier general effective March 13.[16]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "First Loyal Virginia Troops For the Union Cause". George Tyler Moore Center for the Study of the Civil War – Shepherd University. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Battle Unit Details – Union West Virginia Volunteers – 1st Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2017-08-13.

- ↑ Lang 1895, p. 194

- ↑ "Search For Soldiers – The Civil War". National Park Service. Retrieved 2017-08-13.

- ↑ Lang 1895, p. 197

- ↑ "Letter from the Kelley Lancers". The Morgantown Monitor. 1863-02-28. p. 3.

- ↑ "Timeline of West Virginia: Civil War and Statehood November 5–19, 1862". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- ↑ Livingston 1912, p. 766

- ↑ Ellis 1882, p. 771

- ↑ Sutton 2001, p. 89

- ↑ Sutton 2001, p. 44

- ↑ Fallon 1885, p. 140

- ↑ Farrar 1911, p. 13

- ↑ Farrar 1911, p. 15

- ↑ "Rantings of Civil War Historian – Col. Nathaniel P. Richmond". Eric Wittenburg. Retrieved 2017-08-24.

- 1 2 3 Eriksmoen, Curtis (July 11, 2010). "Fargo doctor succeeded Custer in Civil War". The Forum of Fargo-Moorhead. Fargo, North Dakota. Archived from the original on July 12, 2010.

- 1 2 Scott 1885, pp. 355–356

- 1 2 Collins 2013, p. 45

- ↑ Collins 2013, p. 49

- 1 2 3 4 Lang 1895, p. 159

- ↑ "West Virginia Chief Mustering Officers". Army and Navy Official Gazette Vol. II No. 10. 1864-09-06. p. 155.

- ↑ "Battle Detail – Carnifex Ferry". National Park Service. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- ↑ Moore 1864, p. 40

- ↑ Frothingham 1862, pp. 17–19

- ↑ Farrar 1911, p. 22

- ↑ Lang 1895, p. 163

- 1 2 3 4 O'Neill 2012, pp. 67–68

- ↑ Scott & United States War Department 1885, p. 208

- 1 2 Cozzens 2008, p. 112

- ↑ Curry 1898, p. 234

- ↑ Scott & United States War Department 1885, p. 294

- ↑ Scott & United States War Department 1885, p. 492

- ↑ "Order of Battle – Second Manassas". National Park Service. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

- ↑ Collins 2013, p. 71

- ↑ West Virginia & Adjutant General's Office 1866, p. 69

- ↑ O'Neill 2012, p. 66

- ↑ O'Neill 2012, p. 67

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Black 2008, p. Ch.1 of e-book

- ↑ Scott 1889, p. 1104

- ↑ Salmon & Peters 1994, p. 19

- 1 2 Scott 1889, p. 1106

- ↑ Black 2008, p. Last page of Part I of e-book

- 1 2 3 "Chivalrous Exploit of our First Virginia Cavalry in the Recent Engagement at Warrenton Junction". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. 1863-05-11. p. 1.

Mosby first attacked a detachment of the First Virginia cavalry, consisting of about eighty men, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Krepps, while engaged in feeding and watering their horses.

- 1 2 O'Neill 2012, p. 169

- ↑ Lang 1895, p. 164

- ↑ "The New State of West Virginia". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Retrieved 2015-02-21.

- ↑ United States Congress 1891, p. 1005

- 1 2 3 Scott & Lazelle 1889, p. 1018

- ↑ Scott & Lazelle 1889, p. 1008

- ↑ "CWSAC Battle Summaries: Hanover". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ↑ "CWSAC Battle Summaries: Gettysburg". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2017-08-20.

- ↑ Starr 2007, p. 440

- ↑ Johnson & Buel 1884, p. 394

- ↑ Huntington 2013, p. 191

- ↑ Starr 2007, p. 441

- ↑ Wittenberg 2011, p. Ch. 2 of e-book

- ↑ Young 1913, p. 417

- ↑ United States, Congress & Senate 1886, p. 2 Report No. 2887

- ↑ Wittenberg, Petruzzi & Nugent 2008, p. 1

- 1 2 Wittenberg, Petruzzi & Nugent 2008, p. 6

- ↑ Wittenberg, Petruzzi & Nugent 2008, p. 4

- ↑ Wittenberg, Petruzzi & Nugent 2008, p. 39

- 1 2 Wittenberg, Petruzzi & Nugent 2008, pp. 57–58

- 1 2 Wittenberg, Petruzzi & Nugent 2008, p. 65

- ↑ Brown 2005, p. 137

- ↑ Scott & Lazelle 1889, p. 1019

- ↑ "Congressional Medal of Honor Society – Capehart, Charles E." Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- ↑ United States, Congress & Senate 1886, p. 1 Report No. 2887

- ↑ Scott & Lazelle 1889, pp. 1006–1008

- 1 2 Scott & Lazelle 1889, p. 1007

- ↑ Wittenberg 2011, Ch. 16 of e-book

- ↑ Hunt 2014, p. 105

- ↑ Lang 1895, p. 165

- ↑ "The First Virginia Cavalry Regiment Coming". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. 1864-01-28. p. 3.

Five hundred men of the regiment have re-enlisted.

- ↑ "Reception of the First Virginia Cavalry". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. 1864-02-03. p. 2.

The Heroes of 70 Engagements

- ↑ "The First West Virginia Cavalry". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. 1864-03-14. p. 2.

on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

- ↑ Sutton 2001, pp. 113–114

- ↑ Whisonant 2015, p. 80

- ↑ "Dublin, VA". New River VA.com. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- ↑ Duncan 1998, pp. 80–81

- ↑ "Battle Summary – Cove Mountain". National Park Service. Retrieved 2016-02-12.

- ↑ Sutton 2001, p. 117

- ↑ Beyer & Keydel 1907, pp. 344–345

- ↑ "Medal of Honor Recipients – Civil War (A-F) Capehart, Henry". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- 1 2 Sutton 2001, pp. 125–126