1968 Democratic National Convention

|

1968 presidential election | |

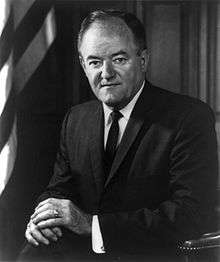

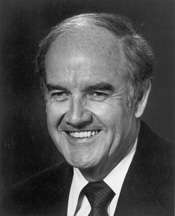

.jpg) Nominees Humphrey and Muskie | |

| Convention | |

|---|---|

| Date(s) | August 26–29, 1968 |

| City | Chicago, Illinois |

| Venue | International Amphitheatre |

| Candidates | |

| Presidential nominee | Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota |

| Vice Presidential nominee | Edmund Muskie of Maine |

| Other candidates |

Eugene McCarthy George McGovern Pigasus |

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois. As President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, the purpose of the convention was to select a new presidential nominee to run as the Democratic Party's candidate for the office.[1] The keynote speaker was Senator Daniel Inouye (D-Hawaii).[2] Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey and Senator Edmund S. Muskie of Maine were nominated for President and Vice President, respectively.

The convention was held during a year of violence, political turbulence, and civil unrest, particularly riots in more than 100 cities[3] following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4.[4] The convention also followed the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy on June 5.[5] Both Kennedy and Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota had been running for the Democratic nomination at the time.

Before the convention

In 1968, which controlled the House of Representatives, the Senate, and the White House, the Democratic Party was divided. Senator Eugene McCarthy entered the campaign in November 1967, challenging incumbent President Johnson for the Democratic nomination. Robert F. Kennedy entered the race in March 1968. Johnson, facing dissent within his party, and having only barely won the New Hampshire primary, dropped out of the race on March 31.[6] Vice President Hubert Humphrey then entered into the race, but did not compete in any primaries; he inherited the delegates previously pledged to Johnson and then collected delegates in caucus states, especially in caucuses controlled by local Democratic party leaders. After Kennedy's assassination on June 5, the Democratic Party's divisions grew.[5] At the moment of Kennedy's death the delegate count stood at Humphrey 561.5, Kennedy 393.5, McCarthy 258.[7] Kennedy's murder left his delegates uncommitted.

Support within the party was divided between Senator McCarthy, who ran a decidedly anti-war campaign and was seen as the peace candidate,[8] Vice President Humphrey, who was seen as the candidate representing the Johnson point of view,[9] and Senator George McGovern, who appealed to some of the Kennedy supporters.

Convention

Before the start of the convention on August 26, several states had competing slates of delegates attempting to be seated at the convention. Some of these delegate credential fights went to the floor of the convention on August 26, where votes were held to determine which slates of delegates representing Texas, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and North Carolina would be seated at the convention. The more racially integrated challenging slate from Texas was defeated.[10]

Nomination

In the end, the Democratic Party nominated Humphrey. Even though 80 percent of the primary voters had been for anti-war candidates, the delegates had defeated the peace plank by 1,567¾ to 1,041¼.[11] The loss was perceived to be the result of President Johnson and Chicago Mayor Richard Daley influencing behind the scenes.[11] Humphrey, who had not entered any of 13 state primary elections, won the Democratic nomination, and went on to lose the election to the Republican Richard Nixon.[12]

Final ballot

| Presidential candidate | Presidential tally | Vice Presidential candidate | Vice Presidential tally |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hubert Humphrey | 1759.25 | Edmund S. Muskie | 1942.5 |

| Eugene McCarthy | 601 | Not Voting | 604.25 |

| George S. McGovern | 146.5 | Julian Bond[13] | 48.5 |

| Channing E. Phillips | 67.5 | David Hoeh | 4 |

| Daniel K. Moore | 17.5 | Edward M. Kennedy | 3.5 |

| Edward M. Kennedy | 12.75 | Eugene McCarthy | 3.0 |

| Paul W. "Bear" Bryant | 1.5 | Others | 16.25 |

| James H. Gray | 0.5 | ||

| George Wallace | 0.5 |

Source: Keating Holland, "All the Votes... Really," CNN[14]

Dan Rather incident

CBS News correspondent Dan Rather was grabbed by security guards and roughed up while trying to interview a Georgia delegate being escorted out of the building.[15] CBS News anchorman Walter Cronkite turned his attention towards the area where Rather was reporting from the convention floor.[15] Rather was grabbed by security guards after he walked towards a delegate who was being hauled out, and asked him "what is your name, sir?" Rather was wearing a microphone headset and was then heard on national television repeatedly saying to the guards "don't push me" and "take your hands off me unless you plan to arrest me".[15]

After the guards let go of Rather, he told Cronkite:

"Walter ... we tried to talk to the man and we got violently pushed out of the way. This is the kind of thing that has been going on outside the hall, this is the first time we've had it happen inside the hall. We ... I'm sorry to be out of breath, but somebody belted me in the stomach during that. What happened is a Georgia delegate, at least he had a Georgia delegate sign on, was being hauled out of the hall. We tried to talk to him to see why, who he was, what the situation was, and at that instant the security people, well as you can see, put me on the deck. I didn't do very well."[15]

An angry Cronkite tersely replied, "I think we've got a bunch of thugs here, Dan."

Richard J. Daley and the convention

Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley intended to showcase his and the city's achievements to national Democrats and the news media. Instead, the proceedings became notorious for the large number of demonstrators and the use of force by the Chicago police during what was supposed to be, in the words of the Yippie activist organizers, "A Festival of Life."[4] Rioting took place by the Chicago Police Department and the Illinois National Guard against the demonstrators. The disturbances were well publicized by the mass media, with some journalists and reporters being caught up in the violence. Network newsmen Mike Wallace, Dan Rather, and Edwin Newman were assaulted by the Chicago police while inside the halls of the Democratic Convention.[16]

The Democratic Presidential Nominating Convention had been held in Chicago 12 years earlier.[17] Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley had played an integral role in the election of John F. Kennedy in 1960.[17] In 1968, however, it did not seem that Daley had maintained the clout which would allow him to bring out the voters again to produce a Democratic victory as he had in 1960.

On October 7, 1967, Daley and Johnson had a private meeting at a fund raiser for President Johnson's re-election campaign, with an entry fee of one thousand dollars per plate (approximately $7,200 in 2016 dollars). During the meeting, Daley explained to the president that there had been a disappointing showing of Democrats in the 1966 congressional races, and the president might lose the swing state with its 27 electoral votes if the convention were not held in Illinois.[18] Johnson's pro-war policies had already created a great division within the party; he hoped that the selection of Chicago for the convention would eliminate further conflict with opposition.[19]

The Committee head for selecting the location was New Jersey Democrat David Wilentz, who gave the official reason for choosing Chicago as, "It is centrally located geographically which will reduce transportation costs and because it has been the site of national conventions for both Parties in the past and is therefore attuned to holding them." The conversation between Johnson and Daley was leaked to the press and published in the Chicago Tribune and several other papers.[19]

Protests and police response

In 1968, the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam and the Youth International Party (Yippies) had already begun planning a youth festival in Chicago to coincide with the Democratic National Convention. They were not alone, as other groups such as Students for a Democratic Society would also make their presence known.[20] When asked about anti-war demonstrators, Daley repeated to reporters that "no thousands will come to our city and take over our streets, our city, our convention."[21] 10,000 demonstrators gathered in Chicago for the convention, where they were met by 23,000 police and National Guardsmen.[12] Daley also thought that one way to prevent demonstrators from coming to Chicago was to refuse to grant permits which would allow for people to protest legally.[22]

After the violence at the Chicago convention, Daley said his primary reason for calling in so many Guardsmen and police was reports he received indicating the existence of plots to assassinate many of the leaders, including himself.[23]

While several protests had taken place before serious violence occurred, the events headed by the Yippies were not without satire. Surrounded by reporters on August 23, 1968, Yippie leader Jerry Rubin, folk singer Phil Ochs, and other activists held their own presidential nominating convention with their candidate Pigasus, an actual pig. When the Yippies paraded Pigasus at the Civic Center, ten policemen arrested Ochs, Rubin, Pigasus, and six others. This resulted in a great deal of media attention for Pigasus.[24]

The Chicago Police riot

On August 28, 1968, around 10,000 protesters gathered in Grant Park for the demonstration. At approximately 3:30 p.m., a young man lowered the American flag that was there.[11] The police broke through the crowd and began beating the young man, while the crowd pelted the police with food, rocks, and chunks of concrete.[25] The chants of some of the protesters shifted from "hell no, we won't go" to "pigs are whores".[26]

Tom Hayden, one of the leaders of Students for a Democratic Society, encouraged protesters to move out of the park to ensure that if the police used tear gas on them, it would have to be done throughout the city.[27] The amount of tear gas used to suppress the protesters was so great that it made its way to the Conrad Hilton hotel, where it disturbed Hubert Humphrey while in his shower.[26] The police sprayed demonstrators and bystanders with mace and were taunted by some protesters with chants of "kill, kill, kill".[28] The police assault in front of the Conrad Hilton hotel the evening of August 28 became the most famous image of the Chicago demonstrations of 1968. The entire event took place live under television lights for seventeen minutes with the crowd chanting, "The whole world is watching".[26]

In its report Rights in Conflict (better known as the Walker Report), the Chicago Study Team that investigated the violent clashes between police and protesters at the convention stated that the police response was characterized by:

unrestrained and indiscriminate police violence on many occasions, particularly at night. That violence was made all the more shocking by the fact that it was often inflicted upon persons who had broken no law, disobeyed no order, made no threat. These included peaceful demonstrators, onlookers, and large numbers of residents who were simply passing through, or happened to live in, the areas where confrontations were occurring.[29][30]

The Walker Report, "headed by an independent observer from Los Angeles police – concluded that: “Individual policemen, and lots of them, committed violent acts far in excess of the requisite force for crowd dispersal or arrest. To read dispassionately the hundreds of statements describing at firsthand the events of Sunday and Monday nights is to become convinced of the presence of what can only be called a police riot.”"[31]

Connecticut Senator Abraham Ribicoff used his nominating speech for George McGovern to report the violence going on outside the convention hall and said that "With George McGovern as President of the United States, we wouldn't have to have Gestapo tactics in the streets of Chicago!"[34] Mayor Daley responded to his remark with something unintelligible through the television sound, although lip-readers throughout America claimed to have observed him shouting, "Fuck you, you Jew son of a bitch." Defenders of the mayor would later claim that he was calling Ribicoff a faker,[32][33] a charge denied by Daley and refuted by Mike Royko's reporting.[35] Ribicoff replied: "How hard it is to accept the truth!" That night, NBC News had been switching back and forth between images of the violence to the festivities over Humphrey's victory in the convention hall, highlighting the division in the Democratic Party.[36]

According to The Guardian, "[a]fter four days and nights of violence, 668 people had been arrested, 425 demonstrators were treated at temporary medical facilities, 200 were treated on the spot, 400 given first aid for tear gas exposure and 110 went to hospital. A total of 192 police officers were injured."[37]

After the Chicago protests, some demonstrators believed the majority of Americans would side with them over what had happened in Chicago, especially because of police behavior.[37] The controversy over the war in Vietnam overshadowed their cause.[16] Daley shared he had received 135,000 letters supporting his actions and only 5,000 condemning them. Public opinion polls demonstrated that the majority of Americans supported the Mayor's tactics.[38] It was often commented through the popular media that on that evening, America decided to vote for Richard Nixon.[39]

The Chicago Seven

After Chicago, the Justice Department meted out charges of conspiracy and incitement to riot in connection with the violence at Chicago. This created the Chicago Eight, consisting of protesters Abbie Hoffman, Tom Hayden, David Dellinger, Rennie Davis, John Froines, Jerry Rubin, Lee Weiner, and Bobby Seale.[40] Demonstrations were held daily during the trial, organized by the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, the Young Lords led by Jose Cha Cha Jimenez, and the local Black Panther Party led by Chairman Fred Hampton. In February 1970, five of the remaining seven Chicago Conspiracy defendants (Seale's charges had been separated from the rest) were convicted on the charge of intent to incite a riot while crossing state lines, but none were found guilty of conspiracy.

Judge Julius Hoffman sentenced the defendants and their attorneys to jail terms ranging from two-and-a-half months to four years for contempt of court.[41] In 1972, the convictions were reversed on appeal, and the government declined to bring the case to trial again.[40][42]

The McGovern–Fraser Commission

In response to the party disunity and electoral failure that came out of the convention, the party established the 'Commission on Party Structure and Delegate Selection' (informally known as the 'McGovern–Fraser Commission'),[43] to examine current rules on the ways candidates were nominated and make recommendations designed to broaden participation and enable better representation for minorities and others who were underrepresented. The Commission established more open procedures and affirmative action guidelines for selecting delegates. In addition the commission required all delegate selection procedures to be open; party leaders could no longer handpick the convention delegates in secret.[44] An unforeseen result of these rules was a large shift toward state presidential primaries. Prior to the reforms, Democrats in two-thirds of the states used state conventions to choose convention delegates. In the post-reform era, over three-quarters of the states use primary elections to choose delegates, and over 80% of convention delegates are selected in these primaries.[45]

See also

- 1968 Republican National Convention

- Protests of 1968

- United States presidential election, 1968

- History of the United States Democratic Party

- List of Democratic National Conventions

- U.S. presidential nomination convention

- Democratic Party presidential primaries, 1968

- Hubert Humphrey presidential campaign, 1968

- Superdelegate, a US Democratic Party class of delegate which originated immediately after the 1968 national convention[46]

References

- ↑ "Past Convention Coverage". The New York Times. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ↑ "Keynoter Knows Sting of Bias, Poverty". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. August 27, 1968.

- ↑ "1968: Martin Luther King shot dead". On this Day. BBC. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- 1 2 Blake, Bailey (1992). The 60s. New York: Mallard Press.

- 1 2 Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr. (1968). Robert Kennedy and His Times. New York: Ballantine Books. p. xi.

- ↑ LBJ Address to Nation, LBJ Presidential Library

- ↑ The Killing of Robert F. Kennedy, Dan E. Moldea

- ↑ Farber 1988: 100.

- ↑ Farber 1988: 93.

- ↑ Max Frankel (August 28, 1968). "Connally Slate Wins Floor Fight; Humphrey Forces Gain Over Rivals by Seating of the Texas Regulars; Connally's Slate Wins Fight for Convention Seats as Humphrey Gains Over Rivals". The New York Times.

- 1 2 3 Gitlin 1987: 331.

- 1 2 Jennings & Brewster 1998: 413.

- ↑ Julian Bond was only 28 at the time and thus constitutionally ineligible to the office of Vice President. At the convention, he addressed the delegates to point this out and withdrew his name from consideration.

- ↑ "AllPolitics – 1996 GOP NRC – All The Votes...Really". CNN.

- 1 2 3 4 "Dan Rather: A Reporter Remembers". CBS News.

- 1 2 Gitlin 1987: 335.

- 1 2 Farber 1988: 115.

- ↑ Farber 1988: 116.

- 1 2 Farber 1988: 117.

- ↑ Farber 1988: 5.

- ↑ Gill, Donna. "LBJ-Humphrey Slate Seen by Party Leader". Chicago Tribune, January 9, 1968, p.2.

- ↑ Gitlin 1987: 319.

- ↑ CBS News, Convention Outtakes, Daley/Cronkite Interview August 29, 1968.

- ↑ Farber 1988: 167.

- ↑ Farber 1988: 195.

- 1 2 3 Gitlin 1987: 332.

- ↑ Farber 1988: 196.

- ↑ Gitlin 1987: 333.

- ↑ Federal Judiciary Center, http://www.fjc.gov/history/home.nsf/page/tu_chicago7_doc_13.html

- ↑ Joyce, Peter; Wayne, Neil (2014). Palgrave Dictionary of Public Order Policing, Protest and Political Violence. p. 75.

- ↑ Taylor, D. & Morris, S. (August 19, 2018). The whole world is watching: How the 1968 Chicago 'police riot' shocked America and divided the nation. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2018/aug/19/the-whole-world-is-watching-chicago-police-riot-vietnam-war-regan

- 1 2 Marc, Schogol. "Views differ on impact of religious bias in race", Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, August 9, 2000. Accessed May 21, 2007. "Chicago Mayor Richard Daley cursed Ribicoff with an anti-Semitic slur at the raucous 1968 Democratic National Convention."

- 1 2 Singh, Robert. "American Government and Politics: A Concise Introduction", Sage Publications (2003), p. 106. "Chicago police assaulted anti-war protesters, while inside turmoil engulfed proceedings and Chicago boss Richard Daley hurled anti-Semitic abuse at Senator Abraham Ribicoff (Democratic, Connecticut)."

- ↑ Farber 1988: 201.

- ↑ Royko, p. 189.

- ↑ NBC Morning News, August 29, 1968.

- 1 2 Taylor, D. & Morris, S. (August 19, 2018). The whole world is watching: How the 1968 Chicago 'police riot' shocked America and divided the nation. The Guardian.

- ↑ Bogart, Leo (1985). Polls and the Awareness of Public Opinion (initially published under the title "Silent Politics"). Transaction Publishers. p. 235. ISBN 9781412831505.

- ↑ Farber 1988: 206.

- 1 2 Gitlin 1987: 342.

- ↑ Davis, R. (September 15, 2008). The Chicago Seven trial and the 1968 Democratic National Convention. The Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ Schmich, M. (August 17, 2018). The Chicago Seven put their fate in her hands. One juror's rarely seen trial journals reveal how that changed her forever. The Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ "McGovern-Fraser Commission created by Democratic Party". JusticeLearning. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ↑ Satterthwaite, Shad. "How did party conventions come about and what purpose do they serve?". ThisNation.com. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ↑ Kaufmann, Karen M.; James G. Gimpel; Adam H. Hoffman (2003). "A Promise Fulfilled? Open Primaries and Representation". The Journal of Politics. 65 (2): 457–476. JSTOR 3449815.

- ↑ Branko Marcetic, "The Secret History of Super Delegates," In These Times, vol. 40, no. 6 (June 2016), pg. 21.

Further reading

- David Farber. Chicago '68. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

- Todd Gitlin. The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage. Toronto: Bantam Books, 1987.

- Peter Jennings and Todd Brewster. The Century. New York: Doubleday, 1998

- Frank Kusch. Battleground Chicago: The Police and the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

- Norman Mailer. Miami and the Siege of Chicago. New York: New American Library, 1968.

- Rick Perlstein. Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America. New York: Scribner, 1968.

- John Schultz. No One Was Killed: The Democratic National Convention, August 1968. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

External links

- Democratic Party Platform of 1968 at The American Presidency Project

- Humphrey Nomination Acceptance Speech for President at DNC (transcript) at The American Presidency Project

- "1968 Democratic Convention" from C-SPAN.org. National Cable Satellite Corporation, 2014.

- "Video clips of confrontations between demonstrators and police". Archived from the original (RealMedia) on May 28, 2008.

- "Yippie-produced documentary on the Convention". Archived from the original (RealMedia) on May 28, 2008.

- "Dementia in the Second City" from Time, September 6, 1968.

- "The Chicago Convention: A Baptism Called A Burial" by Jo Freeman (1968)

- "Chicago '68" by Alvin Susumu Tokunow (1968)

- "1968 Democratic National Convention" at Smithsonian Magazine

- "Chicago '68: A Chronology"

- "Young Lords in Lincoln Park"

- "Chicago '68: An Introduction" by Dean Blobaum (2000)

- "American Experience: Chicago 1968"

- "Retrospective on the 1968 Democratic Convention" from NewsHour.

- "History Files: Parades, Protests and Politics"

- "Grooving in Chi" by Terry Southern from Esquire (1968)

- "Brief History of Chicago's 1968 Democratic Convention" from Allhistory, CNN and Time.

- "Whole World Watching" by John Callaway

- An excerpt from Chicago '68 by David Farber

- An excerpt from No One Was Killed: The Democratic National Convention, August 1968 by John Schultz

- An excerpt from Battleground Chicago: The Police and the 1968 Democratic National Convention by Frank Kusch

- Interview on the Chicago Convention, with Phil Ochs

- Origins of the Young Lords

- Video of Humphrey nomination acceptance speech for President at DNC (via YouTube)

- Audio of Humphrey nomination acceptance speech for President at DNC

- Video of Muskie nomination acceptance speech for Vice President at DNC (via YouTube)

- Audio of Muskie nomination acceptance speech for Vice President at DNC

| Preceded by 1964 Atlantic City, New Jersey |

Democratic National Conventions | Succeeded by 1972 Miami Beach, Florida |