1924 Democratic National Convention

|

1924 presidential election | |

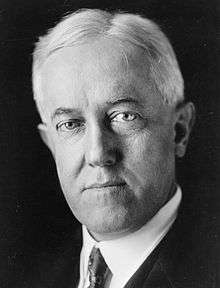

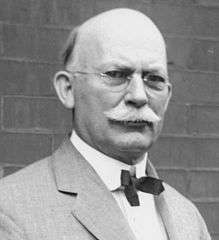

.jpg) .jpg) Nominees Davis and Bryan | |

| Convention | |

|---|---|

| Date(s) | June 24 – July 9, 1924 |

| City | New York, New York |

| Venue | Madison Square Garden |

| Candidates | |

| Presidential nominee | John W. Davis of West Virginia |

| Vice Presidential nominee | Charles W. Bryan of Nebraska |

The 1924 Democratic National Convention, held at the Madison Square Garden in New York City from June 24 to July 9, 1924, was the longest continuously running convention in United States political history. It took a record 103 ballots to nominate a presidential candidate. It was the first major party national convention that saw the name of a woman, Lena Springs, placed in nomination for the office of Vice President. John W. Davis, a dark horse, eventually won the presidential nomination on the 103rd ballot, a compromise candidate following a protracted convention fight between distant front-runners William Gibbs McAdoo and Al Smith.

Davis and his vice presidential running-mate, Charles W. Bryan of Nebraska, went on to be defeated by the Republican ticket of President Calvin Coolidge and Charles G. Dawes in the 1924 presidential election.

Site selection

The selection of New York as the site for the 1924 convention was based in part on the recent success of the party in that state. Two years earlier, in 1922, thirteen Republican congressmen had lost their seats to Democrats. New York had not been chosen for a convention since 1868. Wealthy New Yorkers, who had outbid other cities, declared their purpose "to convince the rest of the country that the town was not the red-light menace generally conceived by the sticks". Though "dry" organizations that supported continuing the prohibition of alcohol opposed the choice of New York, it won McAdoo's grudging consent in the fall of 1923, before the oil scandals made Smith a serious threat to him. (McAdoo's candidacy was hurt by the revelation that he had accepted money from Edward L. Doheny, an oil tycoon implicated in the Teapot Dome scandal.) McAdoo's own adopted state, California, had played host to the Democrats in 1920.[1]

The primaries

McAdoo swept the primaries in the first real race in the history of the party, although most states chose delegates through machines and conventions, giving most of their projected votes to local or hometown candidates, referred to as "favorite sons".

Ku Klux Klan presence

| |

|

|

The Ku Klux Klan had surged in popularity after World War I, due to its leadership's connections to passage of the successful Prohibition Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.[3] This made the Klan a political power throughout many regions of the United States, and it reached the apex of its power in the mid-1920s, when it exerted deep cultural and political influence on both Republicans and Democrats.[4] Its supporters had successfully quashed an anti-Klan resolution before it ever went to a floor vote at the 1924 Republican National Convention earlier in June, and proponents expected to exert the same influence at the Democratic convention. Instead, tension between pro- and anti-Klan delegates produced an intense and sometimes violent showdown between convention attendees from the states of Colorado and Missouri.[4][5] Klan delegates opposed the nomination of New York Governor Al Smith because Smith was a Roman Catholic and an opponent of Prohibition, and most supported William Gibbs McAdoo. Non-Klan delegates, led by Sen. Oscar Underwood of Alabama, attempted to add condemnation of the organization for its violence to the Democratic Party's platform. The measure was narrowly defeated, and the anti-KKK plank was not included in the platform.[4]

Roosevelt comeback

Smith's name was placed into nomination by Franklin D. Roosevelt, in a speech in which Roosevelt dubbed Smith "The Happy Warrior".[6] Roosevelt's speech, which has since become a well-studied example of political oratory,[7] was his first major political appearance since the paralytic illness he had contracted in 1921.[8] The success of this speech and his other convention efforts in support of Smith signaled that he was still a viable figure in politics, and he nominated Smith again in 1928.[9] Roosevelt succeeded Smith as governor in 1929, and went on to win election as president in 1932.[10]

Results

Presidential candidates

.jpg)

The first day of balloting (June 30) brought the predicted deadlock between the leading aspirants for the nomination, William G. McAdoo of California and Gov. Alfred E. Smith of New York, with the remainder divided mainly between local "favorite sons". McAdoo was the leader from the outset, and both he and Smith made small gains in the day's fifteen ballots, but the prevailing belief among the delegates was that the impasse could only be broken by the elimination of both McAdoo and Smith and the selection of one of the other contenders; much interest centred about the candidacy of John W. Davis, who also increased his vote during the day from 31 to 61 (with a peak of 64.5 votes on the 13th and 14th ballots). Most of the favorite son delegations refused to be stampeded to either of the leading candidates and were in no hurry to retire from the contest.

In the early balloting many delegations appeared to be jockeying for position, and some of the original votes were purely complimentary and seemed to conceal the real sentiments of the delegates. Louisiana, for example, which was bound by the "unit rule" (all the state's delegate votes would be cast in favor of the candidate favored by a majority of them), first complimented its neighbor Arkansas by casting its 20 votes for Sen. Joseph T. Robinson, then it switched to Sen. Carter Glass, and on another ballot Maryland Gov. Albert C. Ritchie got the twenty, before the delegation finally settled on John W. Davis.

There was some excitement on the tenth ballot, when Kansas abandoned Gov. Jonathan M. Davis and threw its votes to McAdoo. There was an instant uproar among McAdoo delegates and supporters, and a parade was started around the hall, the Kansas standard leading, with those of all the other McAdoo states coming along behind, and pictures of "McAdoo, Democracy's Hope", being lifted up. After six minutes the chairman's gavel brought order and the roll call resumed, and soon the other side had something to cheer, when New Jersey made its favorite son, Gov. George S. Silzer, walk the plank and threw its votes into the Smith column. This started another parade, the New York and New Jersey standards leading those of the other Smith delegations around the hall while the band played "Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, the Boys are Marching".

First ballot

| Democratic National Convention presidential vote, 1st ballot[11] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Votes | Percentage | |||

| William G. McAdoo | 431.5 | 39.4% | |||

| Alfred E. Smith | 241 | 22.0% | |||

| James M. Cox | 59 | 5.4% | |||

| Pat Harrison | 43.5 | 4.0% | |||

| Oscar W. Underwood | 42.5 | 3.9% | |||

| George S. Silzer | 38 | 3.5% | |||

| John W. Davis | 31 | 2.8% | |||

| Samuel M. Ralston | 30 | 2.7% | |||

| Woodbridge N. Ferris | 30 | 2.7% | |||

| Carter Glass | 25 | 2.3% | |||

| Albert C. Ritchie | 22.5 | 2.1% | |||

| Joseph T. Robinson | 21 | 1.9% | |||

| Jonathan M. Davis | 20 | 1.8% | |||

| Charles W. Bryan | 18 | 1.6% | |||

| Fred H. Brown | 17 | 1.6% | |||

| William Ellery Sweet | 12 | 1.1% | |||

| Willard Saulsbury | 7 | 0.6% | |||

| John Kendrick | 6 | 0.5% | |||

| Houston Thompson | 1 | 0.1% | |||

Fifteenth ballot

| Democratic National Convention presidential vote, 15th ballot[11] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Votes | Percentage | |||

| William G. McAdoo | 479 | 43.6% | |||

| Alfred E. Smith | 305.5 | 27.8% | |||

| John W. Davis | 61 | 5.6% | |||

| James M. Cox | 60 | 5.5% | |||

| Oscar W. Underwood | 39.5 | 3.6% | |||

| Samuel M. Ralston | 31 | 2.8% | |||

| Carter Glass | 25 | 2.3% | |||

| Pat Harrison | 20.5 | 1.9% | |||

| Joseph T. Robinson | 20.5 | 1.9% | |||

| Albert C. Ritchie | 17.5 | 1.6% | |||

| Jonathan M. Davis | 11 | 1.0% | |||

| Charles W. Bryan | 11 | 1.0% | |||

| Fred H. Brown | 9 | 0.8% | |||

| Willard Saulsbury | 6 | 0.5% | |||

| Thomas J. Walsh | 1 | 0.1% | |||

| Newton D. Baker | 1 | 0.1% | |||

Twentieth ballot

McAdoo and Smith each evolved a strategy to build up his own total slowly. Smith's trick was to plant his extra votes for his opponent, so that McAdoo's strength might later appear to be waning; the Californian countered by holding back his full force, though he had been planning a strong early show. But by no sleight of hand could the convention have been swung around to either contestant. With the party split into two assertive parts, the rule requiring a two-thirds majority for nomination crippled the chances of both candidates by giving a veto each could—and did—use. McAdoo himself wanted to drop the two-thirds rule, but his Protestant supporters preferred to keep their veto over a Catholic candidate, and the South regarded the rule as protection against a northern nominee unfavorable to southern interests. At no point in the balloting did Smith receive more than a single vote from the South and scarcely more than 20 votes from the states west of the Mississippi; he never won more than 368 of the 729 votes needed for nomination, though even this performance was impressive for a Roman Catholic. McAdoo's strength fluctuated more widely, reaching its highest point of 528 on the seventieth ballot. Since both candidates occasionally received purely strategic aid, the nucleus of their support was probably even less. The remainder of the votes were divided among dark horses and favorite sons who had spun high hopes since the Doheny testimony; understandably, they hesitated to withdraw their own candidacies as long as the convention was so clearly divided.

| Democratic National Convention presidential vote, 20th ballot[11] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Votes | Percentage |

| William G. McAdoo | 432 | 39.5% |

| Alfred E. Smith | 307.5 | 28.0% |

| John W. Davis | 122 | 11.3% |

| Oscar W. Underwood | 45.5 | 4.1% |

| Samuel M. Ralston | 30 | 2.7% |

| Carter Glass | 25 | 2.3% |

| Joseph T. Robinson | 21 | 1.9% |

| Albert C. Ritchie | 17.5 | 1.6% |

| Others | 97.5 | 8.6% |

Thirtieth ballot

As time passed, the maneuvers of the two factions took on the character of desperation. Daniel C. Roper even went to Franklin Roosevelt, reportedly to offer Smith second place on a McAdoo ticket. For their part, the Tammany men tried to prolong the convention until the hotel bills were beyond the means of the delegates who had travelled to the convention. The Smith backers also attempted to stampede the delegates by packing the galleries with noisy rooters. Senator James Phelan of California, among others, complained of "New York rowdyism". But the rudeness of Tammany, and particularly the booing accord to Bryan when he spoke to the convention, only steeled the resolution of the country delegates. McAdoo and Bryan both tried to reassemble the convention in another city, perhaps Washington, D.C. or St. Louis.

| Democratic National Convention presidential vote, 30th ballot[11] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Votes | Percentage |

| William G. McAdoo | 415.5 | 37.7% |

| Alfred E. Smith | 323.5 | 29.4% |

| John W. Davis | 126.5 | 11.5% |

| Oscar W. Underwood | 39.5 | 3.6% |

| Samuel M. Ralston | 33 | 3.0% |

| Carter Glass | 24 | 2.2% |

| Joseph T. Robinson | 23 | 2.1% |

| Albert C. Ritchie | 17.5 | 1.6% |

| Others | 95.5 | 9.9% |

Forty-second ballot

| Democratic National Convention presidential vote, 42nd ballot[11] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Votes | Percentage |

| William G. McAdoo | 503.4 | 45.7% |

| Alfred E. Smith | 318.6 | 28.9% |

| John W. Davis | 67 | 6.0% |

| Others | 209.0 | 19.4% |

Sixty-first ballot

As a last resort, McAdoo supporters introduced a motion to eliminate one candidate on each ballot until only five remained, but Smith delegates and those supporting favorite sons managed to defeat the McAdoo strategy. Smith countered by suggesting that all delegates be released from their pledges—to which McAdoo agreed on condition that the two-thirds rule be eliminated—although Smith fully expected that loyalty would prevent the disaffection of Indiana and Illinois votes, both controlled by political bosses friendly to him. Indeed, Senator David Walsh of Massachusetts expressed the sentiment that moved Smith backers: "We must continue to do all that we can to nominate Smith. If it should develop that he cannot be nominated, then McAdoo cannot have it either." For his part, McAdoo would angrily quit the convention once he lost: but the sixty-first inconclusive round—when the convention set a record for length of balloting—was no time to admit defeat.

| Democratic National Convention presidential vote, 61st ballot[11] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Votes | Percentage |

| William G. McAdoo | 469.5 | 42.6% |

| Alfred E. Smith | 335.5 | 30.5% |

| John W. Davis | 60 | 5.4% |

| Others | 233 | 21.5% |

Seventieth ballot

Samuel Moffett Ralston

It had seemed for a time that the nomination could go to Samuel Ralston, an Indiana senator and popular ex-governor. Advanced by the indefatigable boss Thomas Taggart, Ralston's candidacy might look for some support from Bryan, who had written, "Ralston is the most promising of the compromise candidates." Ralston was also a favorite of the Klan and a second choice of many McAdoo men. In 1922 he had launched an attack on parochial schools that the Klan saw as an endorsement of its own views, and he won several normally Republican counties dominated by the Klan. Commenting on the Klan issue, Ralston said that it would create a bad precedent to denounce any organization by name in the platform. Much of Ralston's support came from the South and West—states including Oklahoma, Missouri, and Nevada, with their strong Klan elements. McAdoo himself, according to Claude Bowers, said: "I like the old Senator, like his simplicity, honesty, record"; and it was reported that he told Smith supporters he would withdraw only in favor of Ralston. As with John W. Davis, Ralston had few enemies, and his support from men as divergent as Bryan and Taggart cast him as a possible compromise candidate. He passed Davis, the almost consistent third choice of the convention, on the fifty-second ballot; but Taggart then discouraged the boom for the time being because the McAdoo and Smith phalanxes showed no signs of weakening. On July 8, the eighty-seventh ballot showed a total for Ralston of 93 votes, chiefly from Indiana and Missouri; before the day was over, the Ralston total had risen to almost 200, a larger tally than Davis had ever received. Most of these votes were drawn from McAdoo, to whom they later returned.

Numerous sources indicate that Taggart was not exaggerating when he later said: "We would have nominated Senator Ralston if he had not withdrawn his name at the last minute. It was a near certainty as anything in politics could be. We had pledges of enough delegates that would shift to Ralston on a certain ballot to have nominated him." Ralston himself had wavered on whether to make the race; despite the doctor's stern recommendation not to run and the illness of his wife and son, the Senator had told Taggart that he would be a candidate, albeit a reluctant one. But the three-hundred pound Ralston finally telegraphed his refusal to go on with it; sixty-six years old at the time of the convention, he would die the following year.

| Democratic National Convention presidential vote, 70th ballot[11] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Votes | Percentage |

| William G. McAdoo | 528.5 | 48.0% |

| Alfred E. Smith | 334.5 | 30.4% |

| John W. Davis | 67 | 6.0% |

| Others | 170 | 15.6% |

Seventy-seventh ballot

| Democratic National Convention presidential vote, 77th ballot[11] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Votes | Percentage |

| William G. McAdoo | 513 | 47.7% |

| Alfred E. Smith | 367 | 33.3% |

| John W. Davis | 76.5 | 6.9% |

| Others | 134 | 12.1% |

Eighty-seventh ballot

| Democratic National Convention presidential vote, 87th ballot[11] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Votes | Percentage |

| Alfred E. Smith | 361.5 | 32.8% |

| William G. McAdoo | 333.5 | 30.3% |

| John W. Davis | 66.5 | 6.0% |

| Others | 336.5 | 30.9% |

One hundredth ballot

| Democratic National Convention presidential vote, 100th ballot[11] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Votes | Percentage |

| Alfred E. Smith | 351.5 | 32.4% |

| John W. Davis | 203.5 | 18.7% |

| William G. McAdoo | 190 | 17.5% |

| Edwin T. Meredith | 75.5 | 7.0% |

| Thomas J. Walsh | 52.5 | 4.8% |

| Joseph T. Robinson | 46 | 4.2% |

| Oscar W. Underwood | 41.5 | 3.8% |

| Carter Glass | 35 | 3.2% |

| Josephus Daniels | 24 | 2.2% |

| Robert L. Owen | 20 | 1.8% |

| Albert C. Ritchie | 17.5 | 1.6% |

| James W. Gerard | 10 | 0.9% |

| David F. Houston | 9 | 0.8% |

| Willard Saulsbury | 6 | 0.6% |

| Charles W. Bryan | 2 | 0.2% |

| George L. Berry | 1 | 0.1% |

| Newton D. Baker | 1 | 0.1% |

One hundred third ballot

The nomination, stripped of all honor, finally was awarded to John W. Davis, a compromise candidate, on the one hundred third ballot, after the withdrawal of Smith and McAdoo.[12] Davis had never been a genuine dark horse candidate; he had almost always been third in the balloting, and by the end of the twenty-ninth round he was the betting favorite of New York gamblers. There had been a Davis movement at the 1920 San Francisco convention of considerable size; however, Charles Hamlin wrote in his diary, Davis "frankly said ... that he was not seeking [the nomination] and that if nominated he would accept only as a matter of public duty". For Vice-President, the Democrats nominated the able Charles W. Bryan, governor of Nebraska, brother of William Jennings Bryan, and for many years editor of The Commoner. Loquacious beyond endurance, Bryan attacked the gas companies of Nebraska and bravely tried such socialistic schemes as a municipal ice plant for Lincoln. In 1922 he had won the governorship by promising to lower taxes. Bryan received little more than the necessary two-thirds vote, and no attempt was made to make the choice unanimous; booes were sounding through the Garden. The incongruous teaming of the distinguished Wall Street lawyer and the radical from a prairie state provided not a balanced but a schizoid ticket, and because the selection of Bryan was reputed to be a sop to the radicals, many delegates unfamiliar with Davis's actual record came to identify the lawyer with a conservatism in excess even of that considerable amount he did indeed represent.

Full Balloting

| (1-20) | Presidential Ballot | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th | 13th | 14th | 15th | 16th | 17th | 18th | 19th | 20th | ||||||

| J.W. Davis | 31 | 32 | 34 | 34 | 34.5 | 55.5 | 55 | 57 | 63 | 57.5 | 59 | 60 | 64.5 | 64.5 | 61 | 63 | 64 | 66 | 84.5 | 122 | |||||

| McAdoo | 431.5 | 431 | 437 | 443.6 | 443.1 | 443.1 | 442.6 | 444.6 | 444.6 | 471.6 | 476.3 | 478.5 | 477 | 475.5 | 479 | 478 | 471.5 | 470.5 | 474 | 432 | |||||

| Smith | 241 | 251.5 | 255.5 | 260 | 261 | 261.5 | 261.5 | 273.5 | 278 | 299.5 | 303.2 | 301 | 303.5 | 306.5 | 305.5 | 305.5 | 312.5 | 312.5 | 311.5 | 307.5 | |||||

| Cox | 59 | 61 | 60 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | |||||

| Harrison | 43.5 | 23.5 | 23.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 31.5 | 20.5 | 21.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Underwood | 42.5 | 42 | 42 | 41.5 | 41.5 | 42.5 | 42.5 | 48 | 45.5 | 43.9 | 42.5 | 41.5 | 40.5 | 40.5 | 39.5 | 41.5 | 42 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 45.5 | |||||

| Silzer | 38 | 30 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Ferris | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 6.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Ralston | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30.5 | 30.5 | 32.5 | 31.5 | 31.5 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 30 | 30 | 31 | 30 | |||||

| Glass | 25 | 25 | 29 | 45 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 25.5 | 26 | 25 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 44 | 30 | 30 | 25 | |||||

| Ritchie | 22.5 | 21.5 | 22.5 | 21.5 | 42.9 | 22.9 | 20.9 | 19.9 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 18.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | |||||

| Robinson | 21 | 41 | 41 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 20 | 46 | 28 | 22 | 22 | 21 | |||||

| J.M. Davis | 20 | 23 | 20 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 30 | 29 | 32.4 | 12 | 11 | 13.5 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | |||||

| C.W. Bryan | 18 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 15 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 11 | |||||

| Brown | 17 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 9.9 | 8.5 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Sweet | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Saulsbury | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||||

| Kendrick | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Thompson | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Walsh | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 8 | |||||

| W.J. Bryan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Baker | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Berry | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Krebs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Copeland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Hull | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Hitchcock | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Dever | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | |||||

| (21-40) | Presidential Ballot | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21st | 22nd | 23rd | 24th | 25th | 26th | 27th | 28th | 29th | 30th | 31st | 32nd | 33rd | 34th | 35th | 36th | 37th | 38th | 39th | 40th | ||||||

| J.W. Davis | 125 | 123.5 | 129.5 | 129.5 | 126 | 125 | 128.5 | 126 | 124.5 | 126.5 | 127.5 | 128 | 121 | 107.5 | 107 | 106.5 | 107 | 105 | 71 | 70 | |||||

| McAdoo | 439 | 438.5 | 438.5 | 438.5 | 436.5 | 415.5 | 413 | 412 | 415 | 415.5 | 415.5 | 415.5 | 404.5 | 445 | 439 | 429 | 444.5 | 444 | 499 | 506.4 | |||||

| Smith | 307.5 | 307.5 | 308 | 308 | 308.5 | 311.5 | 316.5 | 316.5 | 321 | 323.5 | 322.5 | 322 | 310.5 | 311 | 323.5 | 323 | 321 | 321 | 320.5 | 315.1 | |||||

| Cox | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 54 | 50 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | |||||

| Underwood | 45.5 | 45.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 38.5 | 41.5 | |||||

| Ralston | 30 | 32 | 32 | 33 | 31 | 32 | 32 | 34 | 34 | 33 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 31 | 33 | 33.5 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 31 | |||||

| Glass | 24 | 25 | 30 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 29 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 24 | |||||

| Robinson | 22 | 22 | 23 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 24 | 23 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 23 | 24 | |||||

| Ritchie | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 18.5 | 18.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 18.5 | 17.5 | |||||

| Saulsbury | 12 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||||

| Walsh | 8 | 8.5 | 8 | 9 | 16 | 14 | 7 | 7 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| J.M. Davis | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Baker | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Miller | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Pomerene | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Owen | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 25 | 5 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 4 | 4 | |||||

| Daniels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Martin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Gaston | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Gerard | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Doheny | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Jackson | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| (41-60) | Presidential Ballot | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 41st | 42nd | 43rd | 44th | 45th | 46th | 47th | 48th | 49th | 50th | 51st | 52nd | 53rd | 54th | 55th | 56th | 57th | 58th | 59th | 60th | ||||||

| J.W. Davis | 70 | 67 | 71 | 71 | 73 | 71 | 70.5 | 70.5 | 63.5 | 64 | 67.5 | 59 | 63 | 62 | 62.5 | 58.5 | 58.5 | 40.5 | 60 | 60 | |||||

| McAdoo | 504.9 | 503.4 | 483.4 | 484.4 | 483.4 | 486.9 | 484.4 | 483.5 | 462.5 | 461.5 | 442.5 | 413.5 | 423.5 | 427 | 426.5 | 430 | 430 | 495 | 473.5 | 469.5 | |||||

| Smith | 317.6 | 318.6 | 319.1 | 319.1 | 319.1 | 319.1 | 320.1 | 321 | 320.5 | 320.5 | 328 | 320.5 | 320.5 | 320.5 | 320.5 | 320.5 | 320.5 | 331.5 | 331.5 | 330.5 | |||||

| Cox | 55 | 56 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | |||||

| Underwood | 39.5 | 39.5 | 40 | 39 | 38 | 37.5 | 38.5 | 38.5 | 42 | 42.5 | 43 | 38.5 | 42.5 | 40 | 40 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 38 | 40 | 42 | |||||

| Ralston | 30 | 30 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 57 | 58 | 63 | 93 | 94 | 92 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 40.5 | 42.5 | 42.5 | |||||

| Glass | 24 | 28.5 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 25 | 24 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | |||||

| Robinson | 24 | 23 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 45 | 44 | 45 | 44 | 43 | 42 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 23 | 23 | 23 | |||||

| Ritchie | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 17.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | |||||

| Saulsbury | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||||

| Owen | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 24 | 24 | |||||

| J.M. Davis | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Cummings | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Spellacy | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Walsh | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |||||

| Edwards | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| C.W. Bryan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Battle | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Roosevelt | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Behrman | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| (61-80) | Presidential Ballot | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61st | 62nd | 63rd | 64th | 65th | 66th | 67th | 68th | 69th | 70th | 71st | 72nd | 73rd | 74th | 75th | 76th | 77th | 78th | 79th | 80th | ||||||

| J.W. Davis | 60 | 60.5 | 62 | 61.5 | 71.5 | 74.5 | 75.5 | 72.5 | 64 | 67 | 67 | 65 | 66 | 78.5 | 78.5 | 75.5 | 76.5 | 73.5 | 71 | 73.5 | |||||

| McAdoo | 469.5 | 469 | 446.5 | 488.5 | 492 | 495 | 490 | 488.5 | 530 | 528.5 | 528.5 | 527.5 | 528 | 510 | 513 | 513 | 513 | 511 | 507.5 | 454.5 | |||||

| Smith | 335.5 | 338.5 | 315.5 | 325 | 336.5 | 338.5 | 336.5 | 336.5 | 335 | 334 | 334.5 | 334 | 335 | 364 | 366 | 368 | 367 | 363.5 | 366.5 | 367.5 | |||||

| Cox | 54 | 49 | 49 | 54 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Underwood | 42 | 40 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 40 | 39.5 | 46.5 | 46.5 | 38 | 37.5 | 37.5 | 37.5 | 38.5 | 47 | 46.5 | 47.5 | 47.5 | 49 | 50 | 46.5 | |||||

| Ralston | 37.5 | 38.5 | 56 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 6.5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | |||||

| Glass | 25 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 28 | 28 | 29 | 27 | 21 | 17 | 68 | |||||

| Owen | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Robinson | 23 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 23 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 23 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 22.5 | 28.5 | 29.5 | |||||

| Ritchie | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | |||||

| Saulsbury | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||||

| C.W. Bryan | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4.5 | |||||

| Walsh | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4.5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 4 | |||||

| Ferris | 0 | 0 | 28 | 24.5 | 6.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 18 | 17.5 | |||||

| Walsh | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Baker | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 55 | 54 | 57 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 57.5 | 54 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Wheeler | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Rogers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Coolidge | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Daniels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Kevin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Roosevelt | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Gerard | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| (81-100) | Presidential Ballot | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 81st | 82nd | 83rd | 84th | 85th | 86th | 87th | 88th | 89th | 90th | 91st | 92nd | 93rd | 94th | 95th | 96th | 97th | 98th | 99th | 100th | ||||||

| J.W. Davis | 70.5 | 71 | 72.5 | 66 | 68 | 65.5 | 66.5 | 59.5 | 64.5 | 65.5 | 66.5 | 69.5 | 68 | 81.75 | 139.25 | 171.5 | 183.25 | 194.75 | 210 | 203.5 | |||||

| McAdoo | 432 | 413.5 | 418 | 388.5 | 380.5 | 353.5 | 336.5 | 315.5 | 318.5 | 314 | 318 | 310 | 314 | 395 | 417.5 | 421 | 415.5 | 406.5 | 353.5 | 190 | |||||

| Smith | 365 | 366 | 368 | 365 | 363 | 360 | 361.5 | 362 | 357 | 354.5 | 355.5 | 355.5 | 355.5 | 364.5 | 367.5 | 359.5 | 359.5 | 354 | 354 | 351.5 | |||||

| Glass | 73 | 78 | 76 | 72.5 | 67.5 | 72.5 | 71 | 66.5 | 66.5 | 30.5 | 28.5 | 26.5 | 27 | 37 | 34 | 39 | 39 | 36 | 38 | 35 | |||||

| Underwood | 48 | 49 | 48.5 | 40.5 | 40.5 | 38 | 38 | 39 | 41 | 42.5 | 46.5 | 45.25 | 44.75 | 46.25 | 44.25 | 38.5 | 37.25 | 38.25 | 39.5 | 41.5 | |||||

| Robinson | 29.5 | 28.5 | 27.5 | 25 | 27.5 | 25 | 20.5 | 23 | 20.5 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 37 | 31 | 32 | 22 | 25 | 25 | 46 | |||||

| Owen | 21 | 21 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 20 | |||||

| Ritchie | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 23.5 | 23 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 20.5 | 21.5 | 19.5 | 18.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | |||||

| Ferris | 16 | 12 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Walsh | 7 | 4 | 4 | 1.5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3.5 | 5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 52.5 | |||||

| Saulsbury | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||||

| C.W. Bryan | 4.5 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 9.5 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 15 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 2 | |||||

| Ralston | 4 | 24 | 24 | 86 | 87 | 92 | 93 | 98 | 100.5 | 159.5 | 187.5 | 196.75 | 196.25 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Barnett | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Daniels | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 19.5 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 | |||||

| Roosevelt | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Miller | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Wheeler | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Coyne | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Baker | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |||||

| Meredith | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 75.5 | |||||

| Maloney | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| J.M. Davis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Cox | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Cummings | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Houston | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | |||||

| Callahan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Copeland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Stewart | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Marshall | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | |||||

| Berry | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Gerard | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | |||||

| (101-103) | Presidential Ballot | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101st | 102nd | 103rd Before shifts | 103rd After shifts | ||||||

| J.W. Davis | 316 | 415.5 | 575.5 | 844 | |||||

| Underwood | 229.5 | 317 | 250.5 | 102.5 | |||||

| Walsh | 98 | 123 | 84.5 | 58 | |||||

| Glass | 59 | 67 | 79 | 23 | |||||

| Robinson | 22.5 | 21 | 21 | 20 | |||||

| Meredith | 130 | 66.5 | 42.5 | 15.5 | |||||

| McAdoo | 52 | 21 | 14.5 | 11.5 | |||||

| Smith | 121 | 44 | 10.5 | 7.5 | |||||

| Gerard | 16 | 7 | 8 | 7 | |||||

| Hull | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Daniels | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Thompson | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Berry | 0 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Allen | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| C.W. Bryan | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Ritchie | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Owen | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Cummings | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Houston | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Murphree | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Baker | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

Vice presidential nomination

13 names were placed into nomination for Davis's vice-presidential running mate. Early in the process, the permitted length of speeches was limited to five minutes each.

The only ballot was chaotic, with over thirty people, including three women, getting votes. George Berry, a labor union leader from Tennessee, trailed Charles W. Bryan, Governor of Nebraska, by a vote of 332 to 270.5. Bryan had been chosen by a group of party leaders, including Davis and Al Smith.[12] The party leaders first asked Montanan Senator Thomas J. Walsh to run for vice president, but Walsh refused. New Jersey Governor George Sebastian Silzer, Newton D. Baker, and Maryland Governor Albert Ritchie were also considered, but Bryan was proposed as a candidate who could unite the Smith and McAdoo factions.[12] After the end of the first ballot, a cascade of switches from various candidates to Bryan took place, and Bryan was nominated with at least 740 votes. Notably, he remains the only brother of a previous nominee (William Jennings Bryan) to be nominated by a major party.

The official tally was:

| Vice Presidential Balloting, DNC 1924 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First ballot | before shifts | after shifts | ||

| Governor C. W. Bryan | 332 | 739 | ||

| George Berry | 270.5 | 212 | ||

| Bennett Clark | – | 42 | ||

| Lena Springs | 42 | 18 | ||

| Colonel Alvin Owsley | – | 16 | ||

| Governor George S. Silzer | – | 10 | ||

| Mayor John F. Hylan | 109 | 6 | ||

| Governor Jonathan M. Davis | – | 4 | ||

Prayers

Each of the convention's 23 sessions was opened with an invocation by a different nationally prominent clergyman. The choices represented the party's coalition at the time: there were five Episcopalian ministers; three Presbyterians; three Lutherans; two Roman Catholics; two Baptists; two Methodists; one each from the Congregationalists, Disciples of Christ, Unitarians, and Christian Scientists; and two Jewish rabbis. All of the clergy were white men; African-American denominations were not represented.

With the convention deadlocked over the choice of a nominee, some of the invocations became calls for the delegates and candidates to put aside sectionalism and ambition in favor of party unity.[13][14][15]

Among the clergy who spoke to the convention:

- Catholics included His Eminence Patrick Joseph Hayes, Archbishop of New York,[16] and Fr. Francis Patrick Duffy, Chaplain of the New York National Guard.[17]

- Episcopalians, such as Rt. Rev. Thomas F. Gailor, Bishop of Tennessee,[18] and Rev. Wythe Leigh Kinsolving, Chaplain of the Virginian Society of New York.[14]

- The roster included, on different days, two fierce antagonists and frequent debaters on the theory of evolution and Biblical inerrancy, Rev. John Roach Straton, a Baptist conservative,[19] and Rev. Charles Francis Potter, a Unitarian Modernist.[20]

- Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise, founder of the Free Synagogue, who was also a delegate from New York.[21]

- Dr. Frederick Hermann Knubel, president of the United Lutheran Churches in America.[22]

Legacy

In his acceptance speech, Davis made the perfunctory statement that he would enforce the prohibition law, but his conservatism prejudiced him in favor of personal liberty and home rule and he was frequently denounced as a wet. The dry leader Wayne Wheeler complained of Davis's "constant repetition of wet catch phrases like 'personal liberty', 'illegal search and seizure', and 'home rule'". After the convention Davis tried to satisfy both factions of his party, but his support came principally from the same city elements that had backed Cox in 1920.[23] The last surviving participant from the convention is Diana Serra Cary who as a five year old child film star was the convention's Official Mascot.

- This was the first Democratic National Convention broadcast on radio.[24]

- The first seconding address by a woman in either national political parties was given by Izetta Jewel at this convention, seconding John Davis, and Abby Crawford Milton, seconding McAdoo.[25][26]

- During his 1960 campaign, John F. Kennedy cited the dilemma of the Massachusetts delegation at the 1924 Democratic National Convention when making light of his own campaign problems : "Either we must switch to a more liberal candidate or move to a cheaper hotel."[27]

- Both Franklin D. Roosevelt and Al Smith were filmed during the convention by Lee De Forest in DeForest's Phonofilm sound-on-film process. These films are in the Maurice Zouary collection at the Library of Congress.

"Klanbake" meme

In 2015, conservative blogs and Facebook pages started circulating a photo of hooded Klansmen supposedly marching at the 1924 Democratic convention. In early 2017, a pro-Trump Facebook group called "ElectTrump2020" turned the photo into a meme which has since been shared more than 18,000 times on Facebook alone. In fact, the widely circulated photo depicts an anti-immigrant march by Klansmen in Madison, Wisconsin, and has no connection to any political convention. An archivist for the Wisconsin Historical Society, which published the photo in 2001, stated that the society is "painfully aware" that the photo has been "misappropriated and distributed without our permission."[4] The term "Klanbake" appears to have originated in a dispatch by a New York Daily News reporter referring sardonically to the discovery of the KKK presence at the 1924 DNC convention. An investigation by journalist Jennifer Mendelsohn and historian Peter Shulman found no other mention of the term until it was resurrected by a Daily News columnist in 2000.[4][28] In 2010, the conservative news site Breitbart published a series of articles insinuating that the KKK is historically solely a Democratic organization, and hyper-partisan social media helped spread the "Klanbake" meme widely in the following years, helped by the fact that Wikipedia claimed from 2005 to 2018 that the convention was "also called the Klanbake".[4]

See also

References

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr. History of American Presidential Elections 1789–1968. pp. 2467–2470.

- ↑ "A Broken Party (1924): Conventional Wisdom". Retro Report. 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ↑ Laackman, Dale W. (2014). For the Kingdom and the Power (First ed.). S. Woodhouse Books. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-1-893121-98-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mendelsohn, Jennifer; Shulman, Peter A. (15 Mar 2018). "How social media spread a historical lie". The Washington Post. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑ Kent, Frank B. (29 Jun 1924). "Democrats Split Wide Open in Row Over Klan Issue" (Vol. 84, No. 180). Newspapers.com. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin (1928). The Happy Warrior, Alfred E. Smith. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 25–40.

- ↑ Reid, Loren Dudley (1961). American Public Address: Studies in Honor of Albert Craig Baird. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. p. 216.

- ↑ Houck, Davis W.; Kiewe, Amos (2003). FDR's Body Politics: The Rhetoric of Disability. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-58544-233-1.

- ↑ Ryan, Halford Ross (1995). U.S. Presidents as Orators: A Bio-critical Sourcebook. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-313-29059-6.

- ↑ U.S. Presidents as Orators, p. 147.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Murray, Robert K. (1976). The 103rd Ballot: Democrats and the Disaster in Madison Square Garden. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-013124-1.

- 1 2 3 "Democrats Nominate Davis and C. W. Bryan; Former, Acclaimed, Calls Party to Battle; Smith Promises to Work Hard for the Ticket". The New York Times. July 10, 1924. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ↑ "Thrills Come Early in Morning After Session Opens Tamely". The New York Times. July 9, 1924.

- 1 2 Official Report of the Proceedings of the Democratic National Convention, published by the Democratic National Committee (1924), p. 886

- ↑ Official Report of the Proceedings of the Democratic National Convention, published by the Democratic National Committee (1924), p. 948

- ↑ Official Report of the Proceedings of the Democratic National Convention, published by the Democratic National Committee (1924), pp. 3-4

- ↑ Official Report of the Proceedings of the Democratic National Convention, published by the Democratic National Committee (1924), p. 385

- ↑ Official Report of the Proceedings of the Democratic National Convention, published by the Democratic National Committee (1924), p. 45

- ↑ Official Report of the Proceedings of the Democratic National Convention, published by the Democratic National Committee (1924), pp. 221-22

- ↑ Official Report of the Proceedings of the Democratic National Convention, published by the Democratic National Committee (1924), p. 852

- ↑ Official Report of the Proceedings of the Democratic National Convention, published by the Democratic National Committee (1924), p. 227

- ↑ Official Report of the Proceedings of the Democratic National Convention, published by the Democratic National Committee (1924), pp. 538-39

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr. History of American Presidential Elections 1789–1968. pp. 2467–2478.

- ↑ Sterling, Christopher H.; O'Dell, Cary (2011). The Concise Encyclopedia of American Radio. Routledge. p. 258. ISBN 9781135176846.

- ↑ Izetta Jewel, wvencyclopedia.org accessed September 1, 2012

- ↑ Teel, Ray (2006). The Public Press, 1900–1945: The History of American Journalism. p. 109.

- ↑ White, Theodore (1961). The Making of the President 1960. New York: Atheneum Publishers. p. ?.

- ↑ Shapira, Ian (26 September 2017). "No, Dinesh D'Souza, that photo isn't the KKK marching to the Democratic National Convention". washingtonpost.com. The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

Further reading

- Murray, Robert K. (1976). The 103rd Ballot: Democrats and the Disaster in Madison Square Garden. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-013124-1.

External links

- Democratic Party Platform of 1924 at The American Presidency Project

| Preceded by 1920 San Francisco, California |

Democratic National Conventions | Succeeded by 1928 Houston, Texas |