Jacobite rising of 1745

The Jacobite rising of 1745, also known as the Forty-five Rebellion or simply the "45" (Scottish Gaelic: Bliadhna Theàrlaich [ˈbliən̪ˠə ˈhjaːrˠl̪ˠɪç], "The Year of Charles"), was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart, and the House of Stuart. It took place during the War of the Austrian Succession, when the bulk of the British Army was in Europe, and was the last in a series of revolts that began in 1689, with major outbreaks in 1708, 1715 and 1719.

Charles launched the rising on 19 August 1745 at Glenfinnan in the Scottish Highlands, capturing Edinburgh and winning the Battle of Prestonpans in September. At a council in October, the Scots agreed to invade England after Charles assured them of substantial support from English Jacobites and a simultaneous French landing in Southern England. On that basis, the Jacobite army entered England in early November, reaching Derby on 4 December, where they decided to turn back, as neither of Charles' promises had been fulfilled, and they were far from Scotland and outnumbered by government armies. The decision to retreat was supported by the vast majority of the Jacobite leadership, but caused an irretrievable split between the Scots and Charles. Despite victory at the Falkirk Muir in January 1746, the Battle of Culloden in April ended both the Rebellion and significant backing for the Stuart cause. Charles escaped to France, but was unable to win support for another attempt, and died in Rome in 1788.

Background

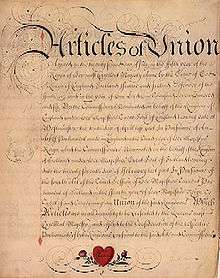

The 1688 Glorious Revolution replaced James II and VII with his Protestant daughter Mary II and her husband William III and II. Since neither Mary nor her sister Anne had surviving children, the 1701 Act of Settlement ensured a Protestant successor by excluding Catholics from the English and Irish thrones, and that of Great Britain after the 1707 Act of Union. When Anne became the last Stuart monarch in 1702, her heir was the distantly related but Protestant Sophia of Hanover, not her Catholic half-brother James Francis Edward. Sophia died two months before Anne in August 1714; her son became George I and the pro-Hanoverian Whigs controlled government for the next 30 years.[2]

Louis XIV was a strong supporter of the Stuarts but after his death in 1715, French priorities were peace and rebuilding their economy.[3] The 1716 Anglo-French alliance forced the Stuarts to leave France and they were invited to settle in Rome by Pope Benedict XIV.[4] The Spanish-sponsored 1719 Rising in Scotland was judged to have done more damage to the Jacobite cause than otherwise, one of its leaders concluding "it bid fair to ruin the King's Interest and faithful subjects in these parts".[5]

Their status as Papal pensionaries and James' devout personal Catholicism made the Stuarts less attractive to Protestant supporters in Britain; a return seemed remote, despite the birth of James' sons Charles and Henry.[6] By 1737, James was reportedly "living tranquilly in Rome, having abandoned all hope of a restoration".[7]

In the late 1730s, various factors improved Stuart prospects. In particular, France was concerned that the post-1713 expansion in British commerce threatened the financial advantage over its rivals provided by the revenue-raising powers of the centralised French state.[8] This made an ongoing, inexpensive civil war that absorbed British resources more useful to France than restoring the Stuarts but potentially devastating for the Scots, as Charles later pointed out.[9] As cost was a primary consideration and French civilian statesmen failed to appreciate the expense of seaborne operations, the result was a great deal of planning for very little action.[10]

The 1725 Malt tax riots in Glasgow and 1737 Porteous Riots in Edinburgh showed a lack of sensitivity by the London government. In March 1743, the Highland-recruited 42nd Regiment or Black Watch was posted to Flanders, despite warnings this was contrary to an understanding their service was restricted to Scotland; the move went ahead regardless, leading to a mutiny.[11] These issues would be exploited by the Scottish Jacobites.

In 1739, trade disputes between Spain and Britain led to the War of Jenkins' Ear, followed in 1740-41 by that of the War of the Austrian Succession. The long-serving British Prime Minister Robert Walpole was forced to resign in February 1742 by an alliance of Tories and pro-war Patriot Whigs who promptly did a deal to keep their partners out of government.[12] Fury at this led junior Tories including the Duke of Beaufort to request French help in restoring James to the British throne, while the Scots made a similar request to restore him to the throne of Scotland and dissolve the Union. French Chief Minister Cardinal Fleury viewed Jacobite claims with scepticism and ignored both requests.[13]

Despite refusing to support the half-hearted 1734-1735 Cornbury conspiracy, [14] French politicians increasingly felt Britain had gained more than France from the 1716 Alliance. When Fleury died in January 1743 and Louis XV took control of government, the two countries were not yet at war but hostilities appeared imminent, making the Jacobites more useful.[15]

Post-1715; Jacobitism in the British Isles

In 1745, supporters of the exiled Stuarts, or "Jacobites",[lower-alpha 1] remained a significant element in British and Irish politics but with different and often competing goals. Many of Charles' advisors were exiles from the French Irish Brigade like John O'Sullivan who wanted an autonomous, Catholic Ireland and the return of lands confiscated from Catholic landowners after the Irish Confederate Wars.[16] James II promised this in return for Irish support in the 1689-1692 Williamite War but with reluctance, the Stuarts themselves being absolutist Unionists.[17]

In England and Wales, most sympathisers were Protestant Church of England Tories but the bulk of those who actively participated in the 1715 rising were from traditional Catholic areas in North-West England. Jacobite strategy in 1745 failed to appreciate this fact and the post-1715 decline in English and Welsh Jacobite support.[18] In August 1743, French agents were given lists of potential supporters, one claiming 190 of the 236 members of the Tory-dominated Corporation of London as "Jacobite".[19] British dislike of European entanglements has a long history and Tory objections to Hanover stemmed largely from policy divergences with the Whigs, rather than Stuart loyalism.[20] Jacobite support was overstated by confusing indifference to the Hanoverians with enthusiasm for the alternative.[21]

In Wales, traditional Tories viewed Methodist evangelism as a threat to the established Church and this was a primary driver for many pre- and post-1745 "Jacobite" displays.[22] The Denbighshire landowner and Tory MP Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn headed the Jacobite White Rose society and met with Stuart agents several times between 1740-1744. On each occasion, he made it clear support depended on Charles bringing a French army; he spent the Rebellion in London, with participation by the Welsh gentry limited to two lawyers, David Morgan and William Vaughan.[23]

After the failed 1719 Rising, new laws actively discriminated against Non-Juring clergy or those who refused to swear allegiance to the Hanoverian regime.[24] Their impact was limited in England, where the established Church was Episcopalian but in Scotland, where the kirk was Calvinist and Presbyterian, Episcopalian congregations preserved their independence. By 1740, less than 2% of Scots were Catholics, mostly in remote Gaelic-speaking areas but Non-Juring Episcopalianism became a mark of Jacobite commitment. It was often associated with powerful local leaders, since congregations required political protection; a high percentage of both Lowlanders and Highlanders who participated in the 1745 Rebellion came from this element of Scottish society,[25] and the majority of the rebellion's leaders were Episcopalians.[26] In addition, the 1707 Acts of Union were extremely unpopular in Scotland, where loss of political control had not been matched by the promised economic benefits.[27]

In summary, the vast majority of Scottish Jacobites were Protestant Episcopalian nationalists who opposed the Union, "arbitrary" rule and Catholicism.[28] This meant the bulk of Charles's Scottish support ultimately disagreed with his aim of reclaiming a united throne of Great Britain for his father, as well as with the Stuart belief in the divine right of kings, French-inspired absolutism and advocacy of tolerance for Catholics. While these attitudes characterised the exile community around the Jacobite court in Saint-Germain, very few Scots, compared to English or Irish, were historically members of the court.[29] Divisions between the Scots and the Irish exiles became increasingly visible during the 1745 Rising and help explain why it was both the most successful and last Jacobite rebellion.

Charles in Scotland

In November 1743, Louis notified his uncle Philip V of Spain and James in Rome of his decision to launch a cross-channel invasion in February.[30] 12,000 troops were assembled at Dunkirk; once French naval forces had lured the Royal Navy away from the Channel, the troops would board the transports and land near London.[31] Since success depended upon speed and surprise, James remained in Rome while Charles travelled in secret to Gravelines in France to join the invasion.[32]

These efforts were wasted since the plan was leaked; when a French squadron left Brest on 26 January the Royal Navy refused to follow.[33] Storms then sank 12 French ships and severely damaged the transports, while the British government arrested a number of suspected Jacobites.[34] At the end of March, Louis cancelled the invasion, declared war on Britain in October and focused on campaigns in Europe.[35]

Charles suggested an alternative landing in Scotland and came to Paris to argue his case, meeting Murray of Broughton there in August 1744. Murray later said he advised against the idea but Charles replied he was "determined to come the following summer [...] though with a single footman".[36] Hearing of Charles' intentions, the Scottish Jacobites reiterated their opposition to a rising without French military support but Charles gambled once he reached Scotland, the French would be forced to support him.[37]

Charles spent the first months of 1745 purchasing weapons, while victory at Fontenoy in April encouraged the French government to provide limited support. This comprised 700 volunteers from the Regiment du Clare of the French Army's Irish Brigade and two transport ships: Elizabeth a 64-gun warship captured from the British in 1704 and the 16-gun privateer Du Teillay.[38]

In early July, Charles boarded Du Teillay at Saint-Nazaire accompanied by seven companions later known as the "Seven Men of Moidart".[39] The most prominent was John O'Sullivan, an Irish exile and former French Army officer, who acted as Charles' chief advisor. After meeting Elizabeth, the two ships left for the Western Isles on 15 July but were intercepted four days out by the British warship HMS Lion. A four-hour battle left both Lion and Elizabeth so badly damaged they had to return to port. This was a major setback as Elizabeth carried most of the weapons and the Irish volunteers, but Du Teillay continued and Charles landed on Eriskay on 23 July.[40]

The vast majority of their assumed supporters, including MacDonald of Boisdale, the Presbyterian MacDonald of Sleat and Norman MacLeod of MacLeod, advised Charles to return to France.[41] Enough were eventually persuaded, including the influential Donald Cameron of Lochiel, but the choice was rarely simple. Lochiel committed only when Charles provided 'security for the full value of his estate should the rising prove abortive;'MacLeod and Sleat raised pro-government militia but actively facilitated Charles' escape after Culloden.[42]

On 19 August, Charles launched the rebellion by raising the Royal Standard at Glenfinnan; he now had a force of about 1,000, largely drawn from Lochiel's tenants.[lower-alpha 2]. The Jacobites advanced towards Edinburgh, reaching Perth on 4 September where they were joined by more sympathisers, among them Lord George Murray. Murray was an experienced soldier pardoned by the government for his role in the 1715 and 1719 risings; he replaced O'Sullivan as commander due to his better understanding of Highland culture and spent the next week re-organising the Jacobite army.[43]

The senior government officer in Scotland, Lord President Duncan Forbes received confirmation of the landing on 9 August, which he forwarded to London.[44] His military commander Sir John Cope had only 3,000 mostly untrained recruits and initially could do little to suppress the rebellion. Forbes instead relied on his personal relationships to keep people loyal and though unsuccessful with Lochiel, Murray and Lord Lovat, many others like MacDonald of Sleat stayed on the sidelines as a result.[45]

On 17 September the Jacobite army entered Edinburgh unopposed, although the Castle itself remained in government hands: the next day James was proclaimed King of Scotland and Charles his Regent.[46] Shortly thereafter, Sir John Cope landed at the port of Dunbar a few miles from Edinburgh; the Jacobites marched out to intercept him and on the early morning of 21 September, they scattered the government army in less than 30 minutes at the Battle of Prestonpans.

The rebellion was now taken more seriously by both its French backers and the government and in mid-October, the Jacobites received a shipment of money and weapons from France with an envoy, the Marquis d'Eguilles. The Duke of Cumberland, George II's younger son and commander of the British army in Europe, was recalled from Flanders with 12,000 troops.[47]

Charles set up a Council of 15-20 senior Jacobite leaders at Edinburgh: it spent the next six weeks debating strategy. At least one Scottish member of the Council, Lord Elcho, later expressed concerns with Charles' autocratic style and noted a fear that he was too influenced by his Irish advisors.[lower-alpha 3] [48] Charles resented the Council as an unwarranted control by the Scots on their divinely appointed monarch; it also emphasised the deep divisions between the Jacobite factions. These became apparent in the meetings held on 30 and 31 October to discuss the invasion of England.[49] The most serious was that caused by Murray of Broughton; seeing Lord George as a threat to his influence, he briefed Charles that Lord George's loyalty was suspect and Charles never overcame his suspicions.[50]

The anti-Union Scots now wanted to consolidate their position; although willing to assist an English rising or French invasion, they would not do it on their own. For the Irish, only a Stuart on the British throne could provide the autonomous, Catholic Ireland promised them by James II. Charles argued removing the Hanoverians was the best guarantee of an independent Scotland and thousands of supporters would join once they entered England, while the Marquis d'Eguilles assured the Council a French landing in England was imminent.[51] Despite their doubts, the Council agreed to the invasion but assuming significant English and French support.[lower-alpha 4]

Most Scottish incursions into England historically crossed the border at Berwick-upon-Tweed. Charles argued in favour of advancing towards Newcastle in order to confront the government army stationed there under General Wade, but to maximise the chances of meeting the two conditions set by the Council, Murray selected a route via Carlisle and the traditional heartland of Jacobite support in North-West England.[52] The last elements of the Jacobite army of about 5,000 [53] left Edinburgh on 4 November: government forces under General Handasyde retook the city on the 14th.[54]

Invasion of England

The Jacobite army formed two columns in order to conceal their destination from General Wade and entered England on 8 November without opposition.[55] Two days later they reached Carlisle, where the castle defences were in poor condition and manned only by 80 elderly veterans. The garrison surrendered on 15 November after learning Wade could not relieve them in time and the Jacobites marched south, leaving a small garrison of their own in place.[lower-alpha 5][56] On 26 November, they reached Preston, site of a major battle in 1715, followed by Manchester on the 28th, where the first significant intake of 200-300 English recruits was formed into the Manchester Regiment. The army entered Derby on 4 December and the Council met the following day to discuss the next steps.[57]

Neither of the conditions agreed in Edinburgh had yet been met. There was no sign of a French landing in England despite repeated claims by d'Eguilles that one was imminent, and while Charles had been received enthusiastically by the populace at Manchester, Ormskirk and Preston,[58] only the first provided any significant number of English recruits.[lower-alpha 6] Similar discussions were held in both Preston and Manchester and several senior officers felt they should have turned back already.[59] Murray argued they had gone as far as possible, but now risked being caught between Cumberland in the south-west and Wade in the north, each army being twice the size of theirs. Charles' admission he had not heard from the English Jacobites since leaving France stunned the Council; this meant he lied when claiming otherwise in Edinburgh and fatally damaged their relationship.[60] Moreover at Derby it was learned that reinforcements from France had landed at Montrose: the Royal Écossais under Drummond and Stapleton's battalion of Irish Picquets, with a supply of good weapons, ammunition, and silver, all much needed. The Council was overwhelmingly in favour of retreat and the next day they left Derby and headed north.[61]

The decision has been debated ever since, but there is no evidence for later claims by exiles there was panic in London on 6 December.[62] Most historians doubt the Hanoverian regime would have fallen even if the Jacobites reached London.[63] The Duke of Richmond who was with Cumberland's army wrote to the Duke of Newcastle on 30 November listing five options for the Jacobites of which retreating to Scotland was by far the best for them and worst for the government.[64] Elcho later wrote that Lord George Murray believed Charles could have successfully continued the war in Scotland "for several years", forcing the Crown to come to terms as their troops were desperately needed for the war on the Continent.[65]

The fast moving Jacobite army evaded pursuit with only a minor skirmish at Clifton Moor, crossing back into Scotland on 20 December. Cumberland's army arrived outside Carlisle on 22 December and seven days later, the garrison was forced to surrender, ending the Jacobite military presence in England.[lower-alpha 7][66]

Road to Culloden

The invasion achieved little but reaching Derby and successfully returning to Scotland was a considerable military achievement. Morale was high and recruits from the Frasers, Mackenzies and Gordons plus drafts from Scottish and Irish regiments in French service brought Jacobite strength to over 8,000.[67] French-supplied artillery was used to besiege Stirling Castle, the strategic key to the Highlands. On 17 January the Jacobites dispersed a relief force under Henry Hawley at the Battle of Falkirk Muir but the siege itself made little progress.[68]

Hawley's forces were largely intact and advanced on Stirling again once Cumberland arrived in Edinburgh on 30 January. Many Highlanders had gone home for the winter and on 1 February the Jacobites abandoned the siege and retreated to Inverness.[69] Cumberland's army entered Aberdeen on 27 February and both sides halted operations until the weather improved.[70]

The Jacobites received several French shipments during the winter but the Royal Navy's blockade led to shortages in both money and food. When Cumberland left Aberdeen on 8 April, Charles and his officers agreed giving battle was their best option, although the choice of ground has been debated by contemporaries and historians ever since. The Highlanders who formed much of the Jacobite army relied on the ferocity of their initial charge to break the enemy line but Cumberland's troops had been intensively drilled in countering this tactic. When successful, it resulted in rapid victories as at Prestonpans and Falkirk but if it failed, they could not hold their ground.[71] With the Jacobite forces exhausted by an ill-advised night march, carried out in a failed attempt to surprise Cumberland's troops in camp, the Battle of Culloden on 16 April was over in less than an hour and ended in a decisive government victory.[lower-alpha 8]

Charles and most of his personal retinue escaped northwards, while an estimated 1,500 survivors assembled at Ruthven Barracks.[72] On 20 April, Charles ordered them to disband, explaining his reasons in a letter of 23rd. He argued the French preferred an ongoing, low-level civil war to decisive victory; since this placed the burden of suffering on the Scots, they should disperse until he returned from France with additional support.[73]

In reality, the breakdown of the relationship between Charles and his Scottish supporters made a successful second campaign unlikely. Even before Derby, Charles had accused Murray and others of treachery; disappointment and his habitual heavy drinking made these outbursts more frequent, while the Scots no longer trusted his promises of support.[74] Elcho claimed to have told Charles he was wrong to abandon his supporters, was still in a much better tactical position than when he started and should "put himself at the head of the 9,000 men that remained to him, and live and die with them", but Charles was determined to make for France. [75] After several months of evading capture in the Western Highlands, Charles was picked up by a French ship on 20 September and never returned.

Aftermath

After Culloden, government forces spent the next few weeks searching for rebels, confiscating cattle and burning Non-Juring Episcopalian and Catholic meeting houses; many of those who participated in the Rebellion came from this element of Scottish society.[76] Prisoners from regiments in the French service were treated as POWs and exchanged, but 3,500 captured Jacobites were indicted for treason. 650 of these died awaiting trial, 120 were executed (including 40 British Army deserters and several officers from the Manchester Regiment), 900 were pardoned and the rest transported.[77] The Jacobite lords Kilmarnock, Balmerino and Lovat were beheaded on Tower Hill in April 1747, but these were among the last executions. Public sympathies had shifted and Cumberland's insistence on severity earned him the nickname 'Butcher' from a City of London alderman.[78]

The 1747 Act of Indemnity pardoned most of those who participated in the Rising, although some were excluded, including Lochiel, who died in France in 1748, Lord Elcho and Lord George Murray. The last to be executed was Doctor Archibald Cameron, younger brother of Lochiel who was convicted of treason for his part in the 45 but escaped into exile; on his return to Scotland in March 1753, he was allegedly betrayed by members of his own clan and executed in London on 7 June.[79]

Steps were taken to prevent future rebellions; William Roy completed the first comprehensive survey of the Highlands,[80] new forts built and the military road network started by Wade after 1715 was finally completed. Additional measures were taken to undermine the traditional clan system, which had been under severe stress even before 1745 due to changing economic conditions.[81] The Heritable Jurisdictions Act ended traditional powers exercised by chiefs over their clansmen while the Act of Proscription outlawed Highland dress unless worn in military service. This Act was repealed in 1782, by which time its purpose had been achieved.

.jpg)

The Jacobite cause did not entirely disappear after 1746 but the exposure of the key factions' conflicting objectives ended it as a serious threat. Many Scots were disillusioned by Charles' leadership while areas in England that were strongly Jacobite in 1715 like Northumberland and County Durham provided minimal support in 1745.[82] Irish Jacobite societies continued but increasingly reflected opposition to the existing order rather than affection for the Stuarts and were absorbed by the Republican United Irishmen. [83]

The Rebellion was the career highlight for both leaders; Cumberland resigned from the Army in 1757 and died of a stroke in 1765. Charles was initially treated as a hero on his return to Paris but the Stuarts were once again barred from France by the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. Henry Stuart's entry into the Catholic Church in June 1747 was seen as tacit acceptance the Jacobites were finished and Charles never forgave him.[84] He continued attempts to reignite the cause, including a secret visit to London in 1750 but habitual heavy drinking made him argumentative and hard to work with. In 1759, he met French Chief Minister de Choiseul to discuss another invasion attempt but Choiseul dismissed him as incapable through drink.[85]

When his father James died in 1766, Pope Clement XIII refused to recognise him as Charles III, despite the strong objections of his brother Henry.[86] Charles never visited Britain again and died in Rome in January 1788, a disappointed and embittered man.

Legacy

Modern writers argue the historic focus on 'Bonnie Prince Charlie' obscures the true legacy of the '45. Since nationalism or opposition to Union was a key driver for many Scottish Jacobites, the Rising should be seen as part of an ongoing political idea, not the last act of a doomed cause and culture.[87] The Jacobite Army is often seen as one composed of Gaelic-speaking Highlanders; while predominantly Scottish, it also contained significant numbers of French and Irish regulars, as well as the English Manchester Regiment. In addition, although many of the Scots were Highlanders, some of the most effective units came from the Lowlands, making it a Scottish rather than Highland force.[88] This confusion still exists; in 2013, the Culloden Visitors Centre listed Lowland regiments such as Lord Elcho's and Balmerino's Life Guards, Baggot's Hussars and Viscount Strathallan’s Perthshire Horse as 'Highland Horse.'[89]

After its failure, Highlanders were converted into a noble warrior race rather than 'Wyld wykkd Helandmen' racially and culturally inferior to other Scots.[90] For decades before 1745, rural poverty drove many to enlist in European armies but while military experience was common, the military aspects of clanship itself had been in decline for many years.[91] Foreign service was banned in 1745 and recruitment into the British Army accelerated as deliberate policy.[92] Victorian Imperial administrators continued this by their policy of recruiting from so-called 'martial races,' groups like Highlanders, Sikhs, Dogras and Gurkhas arbitrarily identified as sharing military virtues.[93] This imagery was both powerful and long-lasting. [lower-alpha 9]

The political divisions of the past led to a focus instead on shared culture; this included the creation of a Scottish literary culture which originated in the Scottish Romantic movement's reaction to Union and included the vernacular poetry of Allan Ramsay. After 1746, Robert Burns continued this trend but others like James MacPherson now looked back to a more distant past that was both Scottish and Gaelic. In the early 19th century, the novelist Sir Walter Scott went further by transforming the Rising and its aftermath into a shared Unionist history. The hero of his novel Waverley is an Englishman who fights for the Stuarts, rescues a Hanoverian Colonel and rejects a romantic Highland beauty in favour of the daughter of a Lowland aristocrat. By 1822, the reconciliation of the Stuart cause with Union allowed Cumberland's Hanoverian nephew George IV to be depicted on a visit to Scotland wearing Highland dress of his own design.

Perspectives were also shaped by 19th-century Scottish art; until the 1860s, the Highlands were portrayed by artists like Horatio McCulloch as wild, remote places largely empty of people.[94] This was gradually replaced by the so-called 'Jacobite Romantic' artists who focused on events from the past, such as John Blake MacDonald's 1879 painting Glencoe, 1692.[95] This created a Scottish identity largely expressed through cultural markers like the Victorian inventions of Burns Suppers, Highland Games and tartans and the adoption by a largely Protestant nation of romantic Catholic icons Mary Queen of Scots and Bonnie Prince Charlie.[96] These views continue to impact modern perspectives of the 1745 Rebellion and Scottish history in general.

In popular culture

In literature, apart from Scott's Waverley novels, the best-known books with the Rebellion as a backdrop include Robert Louis Stevenson's novels Kidnapped and Catriona, the Jacobite trilogy by D.K. Broster and in modern times, Diana Gabaldon's Outlander novels.

Although not strictly related to the '45, British author Joan Aiken wrote a series of children's books set in an alternative 18th-century Britain where James II was never deposed and his son James III battles constant pro-Hanoverian conspiracies.

Significant screen versions include 1948's Bonnie Prince Charlie starring David Niven who summarised it as 'one of those huge, florid extravaganzas that reek of disaster from the start' and Culloden, Peter Watkins' 1964 docu-drama. In addition to the current Outlander TV series, the aftermath of the Rebellion is the theme of the now lost 1966 Dr Who series The Highlanders.

Musical references to the '45 are numerous, both in bagpipe music (e.g. Johnnie Cope) and in song; the most famous is the Skye Boat Song but there are many others, one collection being the 1960 album Songs of Two Rebellions: The Jacobite Wars of 1715 and 1745 in Scotland by Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger. In Argentina, Luca Prodan, the singer of the 80's rock band Sumo, composed the song "Crua chan" in reference to the 1745 events.

Notes

- ↑ Taken from Jacobus, the Latin for James.

- ↑ Not all came willingly. Archibald Cameron, Lochiel's younger brother, was in charge of rounding up recalcitrant Cameron clansmen; resentment at this led to his betrayal and later execution in 1753

- ↑ Elcho stated that the Council consisted of himself; Perth; Lord George Murray; Charles' advisor Sheridan; Murray of Broughton; the Irish Quartermaster-General O'Sullivan; the clan chiefs Lochiel and Keppoch; and clan gentry MacDonald of Clanranald, MacDonald of Glencoe, Stewart of Ardsheal and MacDonnell of Lochgarry. Others were later added.

- ↑ Elcho in his diary wrote that "The majority of the Council was not in favour of a march to England and urged that they should remain in Scotland to watch events and defend their own land. This was also the opinion in secret of the Marquis d‘Eguilles; but the wishes of the Prince prevailed." (Wemyss, 2003, p.85) However, even though the vast majority opposed the invasion, many like Elcho eventually voted in favour since they felt Charles deserved the chance, while also placing strict preconditions on how far they would go.

- ↑ Cumberland wanted to execute those responsible when he retook Carlisle in December.

- ↑ Preston, a Jacobite centre in 1715, provided three, Derby only one, who promptly led his new comrades on a raid of a nearby wine cellar.

- ↑ Much of the garrison came from the Manchester Regiment and treated severely while several of the officers were later executed.

- ↑ The French State Archives contain an account from D'Eguilles in which he claims; The Prince, who believed himself invincible because he had not yet been beaten, defied by enemies whom he thoroughly despised, seeing at their head the son of the rival of his father, proud and haughty, badly advised, perhaps betrayed, could not bring himself to decline battle even for a single day. I requested a quarter of an hour's private audience. There I threw myself in vain at his feet.

- ↑ In his WWII biography 'Quartered Safe Out Here' George MacDonald Fraser refers to a connection between Gurkhas and Highlanders based on that same assumption.

References

- ↑ "Forty-five Rebellion". Britannica. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ↑ Somerset, Anne (2012). Queen Anne; the Politics of Passion. Harper Press. pp. 532–535. ISBN 0007203764.

- ↑ Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688-1788 (First ed.). Manchester University Press. p. 91. ISBN 0719037743.

- ↑ Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688-1788 (First ed.). Manchester University Press. pp. 93–95. ISBN 0719037743.

- ↑ Dickson, William Kirk. "The Jacobite Attempt of 1719; Letters of the Duke of Ormonde to Cardinal Alberoni". Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 7–13. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Blaikie, Walter Biggar (1916). Origins of the Forty-Five, and Other Papers Relating to That Rising. Forgotten Books. p. 57. ISBN 1331341620. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ↑ McKay, Derek (1983). The Rise of the Great Powers 1648-1815 (First ed.). Routledge. pp. 138–140. ISBN 0582485541.

- ↑ RA SP/MAIN/273/117 The Princes' letter to the chiefs, in parting from Scotland 28 April 1746

- ↑ Katherine, Wormeley (2016). Volume 1: Journal and Memoirs of the Marquis D'Argenson. Wentworth Press. pp. 181–182. ISBN 1372987991.

- ↑ Groves Lt-Colonel, Percy (1893). History Of The 42nd Royal Highlanders: The Black Watch, Now The First Battalion The Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) 1729-1893 (2017 ed.). Edinburgh: W. & A. K. Johnston. pp. 3–4. ISBN 1376269481.

- ↑ Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688-1788. Manchester University Press. pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 19–20. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Lord, Evelyn (2004). The Stuart Secret Army: The Hidden History of the English Jacobites. Pearson. p. 137. ISBN 0582772567. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- ↑ Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688-1788 (First ed.). Manchester University Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 0719037743.

- ↑ Harris, Tim (2006). Revolution; the Great Crisis of the British Monarchy 1685-1720. Penguin. pp. 439–444. ISBN 0141016523.

- ↑ Stephen, Jeffrey (January 2010). "Scottish Nationalism and Stuart Unionism". Journal of British Studies. 49 (1, Scottish Special): 55–58.

- ↑ Lord, Evelyn (2004). The Stuarts' Secret Army: English Jacobites, 1689-1752. Pearson. pp. 131–136. ISBN 0582772567.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 22–23. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Shinsuke, Satsuma (2013). Britain and Colonial Maritime War in the Early Eighteenth Century. Overview of arguments used: Boydell Press. p. 37 passim. ISBN 1843838621.

- ↑ Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688-1788 (First ed.). Manchester University Press. pp. 96–98. ISBN 0719037743.

- ↑ Monod, Paul Kleber (1993). Jacobitism and the English People, 1688-1788. Cambridge University Press. pp. 197–199. ISBN 0521447933.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 234–235. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Strong, Rowan (2002). Episcopalianism in Nineteenth-Century Scotland: Religious Responses to a Modernizing Society. OUP Oxford. p. 15. ISBN 0199249229.

- ↑ Szechi, Daniel, Sankey, Margaret (November 2001). "Elite Culture and the Decline of Scottish Jacobitism 1716-1745". Past & Present. 173: 97 passim. JSTOR 3600841.

- ↑ Strong, Rowan (2002). Episcopalianism in Nineteenth-Century Scotland: Religious Responses to a Modernizing Society. OUP Oxford. p. 16. ISBN 0199249229.

- ↑ Lynch (ed), Michael (2001). The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford Quick Reference). OUP. pp. 197–198. ISBN 0199693056.

- ↑ Stephen, Jeffrey (January 2010). "Scottish Nationalism and Stuart Unionism". Journal of British Studies. 49 (1, Scottish Special): 47–72.

- ↑ Corp, "The Scottish Jacobite community at Saint Germain after the departure of the Stuart court" in MacInnes (ed) (2015) Living with Jacobitism, 1690–1788, Routledge, p.29. Scottish exiles made up less than 5% of the court in 1696 and 1709: by far the largest element were English, followed by Irish and French.

- ↑ Cruickshanks, Eveline (1979). Political Untouchables: The Tories and the '45. Holmes & Meier. pp. 50–52. ISBN 0841905118.

- ↑ Duffy, Christopher (2003). The '45: Bonnie Prince Charlie and the untold story of the Jacobite Rising (First ed.). Orion. p. 43. ISBN 0304355259.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. p. 27. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Cruickshanks, Eveline (1979). Political Untouchables: The Tories and the '45. Holmes & Meier. pp. 34–36. ISBN 0841905118.

- ↑ Fremont, Gregory (2011). The Jacobite Rebellion 1745-46. Osprey Publishing. p. 48. ISBN 1846039924.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 27–29. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Murray, John (1898). Memorials of John Murray of Broughton. University Press for the Scottish History Society.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 55–58. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 57–58. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ "The Seven Men of Moidart". 1745association.org.uk. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ↑ Duffy, Christopher (2003). The '45: Bonnie Prince Charlie and the untold story of the Jacobite Rising (First ed.). Orion. p. 43. ISBN 0304355259.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 83–84. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 465–467. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 123–125. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 93–94. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 95–97. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Duffy, Christopher (2003). The '45: Bonnie Prince Charlie and the untold story of the Jacobite Rising (First ed.). Orion. p. 198. ISBN 0304355259.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 198–199. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Lord Elcho, David (2010). A Short Account Of The Affairs Of Scotland In The Years 1744-46 (First published 1748 ed.). Kessinger Publishing. p. 289. ISBN 1163535249.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 175–176. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Wemyss, Alice (2003). Elcho of the '45. Saltire Society. p. 77. ISBN 0854110801.

- ↑ Stephen, Jeffrey (January 2010). "Scottish Nationalism and Stuart Unionism". Journal of British Studies. 49 (1, Scottish Special): 55–58.

- ↑ Stephen, Jeffrey (January 2010). "Scottish Nationalism and Stuart Unionism". Journal of British Studies. 49 (1, Scottish Special): 60–61.

- ↑ Home, Robert (2014). The History of the Rebellion (First published 1802 ed.). Nabu Publishing. pp. 329–333. ISBN 1295587386.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 200–201. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Duffy, Christopher (2003). The '45: Bonnie Prince Charlie and the untold story of the Jacobite Rising (First ed.). Orion. p. 223. ISBN 0304355259.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 209–216. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 298–299. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Pittock, Murray (1998). Jacobitism. Macmillan. p. 115.

- ↑ Maxwell, James (2010). Narrative of Charles Prince of Wales' Expedition to Scotland in the Year 1745 (First published 1841 ed.). Kessinger Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 1165625350.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 299–300. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 304–305. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Winchester, Paul (2017). Memoirs of the Chevalier de Johnstone (First published 1843 ed.). Leopold Publishing. p. 48. ISBN 1356079512.

- ↑ Colley, Linda (2009). Britons: Forging the Nation 1707-1837 (Third ed.). Yale University Press. pp. 72–79. ISBN 9780300152807.

- ↑ BL Add MS 32705 ff.399-400 Richmond to Newcastle. Lichfield 30 November 1745

- ↑ Elcho, "An Extract from the diary of David, Lord Elcho" in Tayler (ed) (1948) A Jacobite Miscellany: Eight Original Papers on the Rising of 1745-6, p.201

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 328–329. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Home, Robert (2014). The History of the Rebellion (First published 1802 ed.). Nabu Publishing. pp. 329–333. ISBN 1295587386.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 343–344. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Home, Robert (2014). The History of the Rebellion (First published 1802 ed.). Nabu Publishing. pp. 353–354. ISBN 1295587386.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 377–378. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Reid, Stuart (1996). British Redcoat 1740-93. Osprey Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 1855325543.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 436–437. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ RA SP/MAIN/273/117 The Princes' letter to the chiefs, in parting from Scotland 28 April 1746

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. p. 493. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Elcho in Tayler (1948), p.207

- ↑ Szechi, Daniel, Sankey, Margaret (November 2001). "Elite Culture and the Decline of Scottish Jacobitism 1716-1745". Past & Present. 173: 97 passim. JSTOR 3600841.

- ↑ Roberts, John (2002). The Jacobite Wars: Scotland and the Military Campaigns of 1715 and 1745. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 196–197. ISBN 1902930290.

- ↑ Lewis, William (1977). Horace Walpole's Correspondence; Volume 19. Yale University Press. pp. 287–288. ISBN 0300007035.

- ↑ Lenman, Bruce (1980). The Jacobite Risings in Britain 1689-1746. Methuen Publishing Ltd. p. 27. ISBN 0413396509.

- ↑ Seymour, W A (1980). A History of the Ordnance Survey. Folkestone: Wm Dawson & Sons Limited. pp. 4–9. ISBN 0 7129 0979 6.

- ↑ Devine, TM (1994). Clanship to Crofters' War: The Social Transformation of the Scottish Highlands. Manchester University Press. p. 16. ISBN 0719034825.

- ↑ "The '45 in Northumberland and Durham". The Northumbrian Jacobite Society. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ↑ Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688-1788. Manchester University Press. p. 133. ISBN 0719037743.

- ↑ Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. pp. 496–497. ISBN 1408819120.

- ↑ Zimmerman, Doron (2003). The Jacobite Movement in Scotland and in Exile, 1746-1759. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 273. ISBN 1349511536.

- ↑ Blaikie, Walter Biggar (1917). Origins of the Forty-Five, and Other Papers Relating to That Rising (2017 ed.). Forgotten Books. ISBN 1331341620.

- ↑ "From Jacobitism to the SNP: the Crown, the Union and the Scottish Question" (PDF) (The Stenton Lecture). November 2013.

- ↑ Aikman, Christian (2001). No Quarter Given: The Muster Roll of Prince Charles Edward Stuart's Army, 1745-46. Neil Wilson Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 1903238021.

- ↑ Pittock, Murray (2016). Great Battles; Culloden (First ed.). OUP Oxford. p. 135. ISBN 0199664072.

- ↑ Devine, TM (1994). Clanship to Crofters' War: The Social Transformation of the Scottish Highlands. Manchester University Press. p. 2. ISBN 0719034825.

- ↑ Mackillop, Andrew (1995). Military Recruiting in the Scottish Highlands 1739-1815: the Political, Social and Economic Context. PHD Thesis University of Glasgow. p. 2.

- ↑ Mackillop, Andrew (1995). Military Recruiting in the Scottish Highlands 1739-1815: the Political, Social and Economic Context. PHD Thesis University of Glasgow. pp. 103–148.

- ↑ Streets, Heather (2010). Martial Races: The Military, Race and Masculinity in British Imperial Culture, 1857-1914. Manchester University Press. p. 52. ISBN 0719069637.

- ↑ McCulloch, Horatio. "Glencoe, 1864". Glasgow Museums. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ MacDonald, John Blake. "Glencoe 1692". Art UK.

- ↑ Morris, RJ (1992). "Victorian Values in Scotland & England". Proceedings of the British Academy (78): 37–39.

Sources

- Aikman, Christian; No Quarter Given: The Muster Roll of Prince Charles Edward Stuart's Army, 1745–46; (Neil Wilson Publishing, 2001);

- Blaikie, Walter Biggar; Origins of the Forty-Five, and Other Papers Relating to That Rising; (Forgotten Books, 2018 first published 2016);

- Chambers, Robert; History of the Rebellion of 1745–1746; (W. & R. Chambers, 1869).

- Colley, Linda; Britons: Forging the Nation 1707–1837; (Yale University Press, 2009 ed);

- Cruickshanks, Eveline; Political Untouchables. The Tories and the '45 (Duckworth, 1979).

- Devine, TM; Clanship to Crofters' War: The Social Transformation of the Scottish Highlands; (Manchester University Press, 1994);

- Duffy, Christopher; The '45 (Cassell, 2003);

- Fremont, Gregory; The Jacobite Rebellion 1745–46; (Osprey Publishing, 2011);

- Home, Robert; The History of the Rebellion; (Nabu Publishing, 2014 ed);

- Hook, Michael and Ross, Walter; The 'Forty-Five. The Last Jacobite Rebellion (Edinburgh: HMSO, The National Library of Scotland, 1995);

- Kennedy, Allan; Managing the Early Modern Periphery: Highland Policy and the Highland Judicial Commission, c. 1692–c. 1705; (Scottish Historical Review, Volume 96 Issue 1, Pages 32–60, ISSN 0036-9241);

- Lenman, Bruce; The Jacobite Risings in Britain, 1689–1746 (Methuen Publishing, 1984);

- Lord Elcho, David; A Short Account Of The Affairs Of Scotland In The Years 1744–46 (1748 ed.); (Kessinger Publishing, 2010);

- Mackillop, Andrew; Military Recruiting in the Scottish Highlands 1739–1815: the Political, Social and Economic Context; (1995 PHD Thesis, University of Glasgow);

- Maxwell, James (ed); Narrative of Charles, Prince of Wales' Expedition to Scotland in the Year 1745 (1841 ed.); (Kessinger Publishing, 2016);

- McGarry, Stephen; Irish Brigades Abroad; (Dublin, 2013)

- McInally, Thomas; Missionaries or Soldiers for the Jacobite Cause? in Douglas J. Hamilton, ed., Jacobitism, Enlightenment and Empire, 1680–1820 (Routledge, 2015).

- McLynn, Frank; The Jacobite Army in England; 1745 The Final Campaign; (John Donald, 1998);

- Morris, RJ; Victorian Values in Scotland & England; (Proceedings of the British Academy, 1992);

- Pittock, Murray; Great Battles; Culloden; (OUP, 2016);

- Reid, Stuart; British Redcoat 1740–93; (Osprey Publishing, 1996);

- Riding, Jacqueline; Jacobites; A New History of the 45 Rebellion (Bloomsbury 2016).

- Roberts, John; The Jacobite Wars: Scotland and the Military Campaigns of 1715 and 1745; (Edinburgh University Press, 2002);

- Speck, WA; The Butcher; the Duke of Cumberland and the Suppression of the 45; (Welsh Academic Press, 1995);

- Stephen, Jeffrey; Scottish Nationalism and Stuart Unionism; (Journal of British Studies, 2010);

- Streets, Heather; Martial Races: The Military, Race and Masculinity in British Imperial Culture, 1857–1914; (Manchester University Press, 2010);

- Szechi, Daniel; The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688–1788 (Manchester University Press, 1994).

- Whitworth, Rex; William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland; A Life; (Leo Cooper, 1992);

- Winchester, Paul (ed); Memoirs of the Chevalier de Johnstone (1843); (Leopold Publishing, 2017);

- Wormeley, Catherine (ed); Journal and Memoirs of the Marquis D'Argenson, Volume 1; (Wentworth Press, 2016);

- Zimmerman, Doron; The Jacobite Movement in Scotland and in Exile, 1746–1759; (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003);

External links

- The Jacobite Rebellion, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Murray Pittock, Stana Nenadic & Allan Macinnes (In Our Time, May 8, 2003).

.svg.png)