Planned French invasion of Britain (1708)

| Planned French Invasion of Britain, 1708 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Jacobite risings | |||||||

James Francis Edward Stuart ca 1708 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Jacobites |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Comte de Pontchartrain Claude de Forbin James Francis Edward Stuart Comte de Gacé |

Admiral Sir George Byng Rear Admiral Baker | ||||||

The Planned French Invasion of Britain, 1708, also known as the 'Entreprise d’Écosse,' took place during the War of the Spanish Succession. The French planned to land 5,000-6,000 soldiers in North-East Scotland to support a rising by local Jacobites that would restore James Francis Edward Stuart to the throne of Great Britain. Leaving Dunkirk in March 1708, the fleet reached Scotland but was unable to disembark the troops and returned home, narrowly escaping a pursuing British naval force.

Background

%2C.jpg)

Under the terms of the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, Louis XIV recognised William III as the legitimate monarch, but when James II died on 16 September 1701, he reneged on this and proclaimed James Francis Edward Stuart King of England and Scotland. In response, the English Parliament passed the Security of the Succession Act; in addition to swearing allegiance to William, office-holders were now also required to deny the Stuart right to the throne.[1]

The War of the Spanish Succession began soon after; William died in March 1702 and was succeeded by the last Stuart monarch, James' Protestant daughter Anne. Since she had no surviving children, the 1701 Act of Settlement ensured a Protestant succession by excluding her Catholic half-brother.

A crushing Allied victory over the French at Ramillies in 1706 gave Britain and the Dutch Republic control of the Spanish Netherlands but by the end of 1707, the war reached apparent stalemate. Both sides attempted to use internal conflicts to break the deadlock; Britain supported the Camisard rebels in South-West France, with the Jacobites serving a similar function for the French.[2]

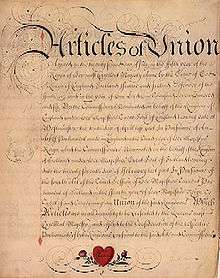

Jacobite agent Nathaniel Hooke convinced French ministers popular discontent provided an opportunity for a Rising in Scotland, which would also help France by diverting British troops from Europe. The 1707 Act of Union was widely unpopular while war severely damaged the Scottish economy; French privateers caused enormous losses for Scottish maritime trade and the coastal fishing industry.[3] Protecting Scottish shipping was not a priority for the Royal Navy, which faced multiple demands on its resources for escorting merchant convoys.[4]

Hooke visited Scotland in 1707, meeting supporters including the Earl of Erroll, a fierce opponent of Union and the elderly Jacobite soldier Thomas Buchan, who provided reports on government bases at Fort William and Inverness.[5] Senior Scots nobles like the Dukes of Atholl and Hamilton refused to commit, partly due to an attempt in 1703 by Simon Fraser, later Lord Lovat, to implicate them in a Jacobite plot as part of a personal feud.[6] However, Hooke obtained a letter of support signed by Erroll, the Earl of Panmure and six others, promising 25,000 men and requesting 8,000 French troops, weapons, money, artillery, ammunition and ‘majors, lieutenants and serjeants to discipline’ the Scots army.[7]

The Presbyterian Church of Scotland saw a separate Parliament of Scotland as a guarantee of independence from the Episcopalian Church of England; despite the Protestant Religion and Presbyterian Church Act, many feared the potential impact of Union.[8] The supposed Jacobite Presbyterian John Ker claimed radical Presbyterians or Cameronians in Scotland and Northern Ireland supported the Stuarts since 'they are persuaded (Union) will bring an infinite number of calamities upon this nation, and will render the Scots slaves to the English.'[9] While the Cameronians were certainly considering this option, Ker was a British government agent paid by the Duke of Queensberry whose role was to persuade them not to join a rebellion.[10]

Louis decided there was enough support to begin planning in November 1707; this was supervised by the Comte de Pontchartrain, who had been involved with previous attempts in 1692 and 1696. Claude de Forbin was appointed commander of the naval squadron, with the Comte de Gacé in charge of the landing force.

The Expedition

%2C_1st_Viscount_Torrington.jpg)

As the Royal Navy patrolled exits from the French Channel ports, naval operations often took place during the winter months, when wind and tides made it harder to enforce a blockade. However, it also increased risks from the weather; conditions off North-East Scotland were well-known to French privateers and de Forbin's biggest concern was lack of a confirmed landing place. He later recorded that 'the Minister did not mention any port which was in a condition to receive us, ...or where our fleet might anchor and... troops disembark in safety.'[11] Based on information supplied by French privateers on conditions in Scotland, de Forbin told Pontchartrain and Louis XIV the expedition would fail, but planning continued.

The fleet assembled at Dunkirk; this was a major French privateer base, since they could reach the Thames in a single tide and customarily raided as far north as the Orkney Islands.[12] By the end of February, 5,000 - 6,000 troops, from the French regiments of Bernay, Auxerre, Agen, Luxembourg, Beauferme, and Boulogne plus elements of the Irish Brigade were ready to embark, James himself arriving on 9 March.[13]

Rather than slow-moving transports, de Forbin insisted on using a larger number of small but fast privateers, many of which reduced their crews and offloaded guns to accommodate the troops.[14] While this improved their chances of avoiding the Royal Navy, the smaller privateers could not hope to defeat British warships in a naval battle.

The British had been monitoring French preparations and a squadron under Sir George Byng now arrived off the nearby port of Gravelines. This prevented the French departure and since James was ill with measles, the troops were disembarked while he recovered. After a week, Byng returned to port for resupply; James and the soldiers were re-loaded and on 17 March the French force of 30 privateers and five warships left Dunkirk.[15]

Although their departure was immediately delayed by a two day gale, it forced the British to take shelter, enabling the French to evade Byng and make for the Firth of Forth. Rather than following the coastline, de Forbin kept the fleet out to sea to avoid being spotted and they ended up north of the proposed landing site. On 25 March, the French anchored near Fife Ness and spent the next day searching for a landing place, allowing Byng to catch up with them. Despite James' protests, de Forbin's light privateers could not face the British in battle and headed north; they then spent two days attempting to enter the Moray Firth before giving up.[16] The bulk of the French fleet made it back to Dunkirk, despite being pursued by the British around the north of Scotland and west of Ireland but sustained severe damage to both ships and men.

Hearing news of the French fleet, some of the Jacobite gentry, including James Stirling of Keir, Archibald Seaton of Touch, Archibald Stirling of Garden, Charles Stirling of Kippendavie, and Patrick Edmonston of Newton gathered at Brig o' Turk. They were arrested, imprisoned in Newgate, then later transferred to Edinburgh Castle where they were tried for high treason.[17] They were acquitted of this charge, as the evidence against them proved only that they had drunk to James' health.[18]

Aftermath

_by_John_Wootton.jpg)

Perceptions of the expedition's value reflect a fundamental divergence of objectives between France and their Jacobite allies. The Stuarts wanted to regain their throne; for the French, they were a useful, low-cost means of absorbing British resources but a Stuart restoration would not change the threat posed by British expansion.[19]

As with the 1696 Plot, the 1708 attempt was a response to the dire military situation France faced as a result of Marlborough's victories in Flanders.[20] It occupied large elements of the British and Dutch navies for several months, with Byng ordered to remain in Scotland even after de Forbin had left for Dunkirk, while troops were moved from the Spanish Netherlands, Ireland and Southern England.[21] A French army of 110,000 invaded the Spanish Netherlands and recaptured large parts of it, before Allied victory at Oudenarde on 11 July evicted them once more. Despite ultimate defeat, for France the expedition largely achieved its short-term purpose.

However, in the long run, it arguably damaged both the Jacobites, who had failed to launch an effective insurgency despite popular opposition to Union, and France; in his overview of the political situation in early 1708, Hooke wrote that 'England (sic) seemed to be fully resolved on peace.'[22] The alarm caused by the invasion attempt helped the pro-war Whigs win a majority in the May 1708 General Election, the first held after Union. This cemented the power of the Godolphin–Marlborough ministry and the war continued.

References

- ↑ Williams, Neville E (1960). The Eighteenth-Century Constitution 1688-1815: Documents and Commentary (2009 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 340. ISBN 9780521091237.

- ↑ Owen, John Hely (1938). War at Sea Under Queen Anne 1702-1708 (2010 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 238. ISBN 1108013384.

- ↑ Whatley, Christopher (2011). Scottish Society, 1707-1830: Beyond Jacobitism, Towards Industrialisation. Manchester University Press. p. 55. ISBN 0719045401.

- ↑ "Lord High Admiral's Answer to the Report of the Committee, upon the Petition of the Merchants complaining of Losses for Want of Cruiz rs and Convoys". Journal of the House of Lords. 18: 405–423. 9 January 1708. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ↑ Hopkins, Paul (2004). "Buchan, Thomas; 1641-1724". Oxford DNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3827. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ↑ Lord, Evelyn (2004). The Stuarts' Secret Army. Pearson. p. 34. ISBN 0582772567.

- ↑ Sinclair-Stevenson, Christopher (April 1971). "The Jacobite Expedition of 1708". History Today. 21 (4). Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ Bowie, Karin (2003). "Public Opinion, Popular Politics and the Union of 1707". The Scottish Historical Review. 82 (214): 229.

- ↑ Sinclair-Stevenson, Christopher (April 1971). "The Jacobite Expedition of 1708". History Today. 21 (4). Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ Douglas, Hugh (2008). "John Ker, of Kersland; 1673-1726". Oxford DNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15449. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ↑ Sinclair-Stevenson, Christopher (April 1971). "The Jacobite Expedition of 1708". History Today. 21 (4). Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ Bromley, JS (1987). Corsairs and Navies, 1600-1760. Continnuum-3PL. p. 233. ISBN 090762877X. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ↑ Owen, John Hely (1938). War at Sea Under Queen Anne 1702-1708 (2010 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 238. ISBN 1108013384.

- ↑ Owen, John Hely (1938). War at Sea Under Queen Anne 1702-1708 (2010 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 250. ISBN 1108013384.

- ↑ Lenman, Bruce (1980). The Jacobite risings in Britain 1689-1746 ([1st ed.]. ed.). London: Eyre Methuen. p. 88. ISBN 0413396509.

- ↑ Owen, John Hely (1938). War at Sea Under Queen Anne 1702-1708 (2010 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 255–263. ISBN 1108013384.

- ↑ Mitchell, John Oswald (1905). Old Glasgow essays. Glasgow: J Maclehose. p. 87.

- ↑ Cobbett, William (1828) [1719]. "The Trials of James Stirling of Keir". In Howell, T B. State Trials. XIV. London: Longman. p. 1395.

- ↑ Macinnes, AI (October 1984). "Jacobitism". History Today. 34 (10).

- ↑ Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688-1788 (First ed.). Manchester University Press. p. 56. ISBN 0719037743.

- ↑ Owen, John Hely (1938). War at Sea Under Queen Anne 1702-1708 (2010 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 268–270. ISBN 1108013384.

- ↑ Hooke, Nathaniel (1760). Secret History Of Colonel Hoocke's Negotiations In Scotland In Favour Of The Pretender In 1707: Including The Original Letters And Papers Which Passed Versailles And St. Germains (2011 ed.). Nabu. p. 172. ISBN 1247343642.

Sources

- Bowie, Karin; Public Opinion, Popular Politics and the Union of 1707; (The Scottish Historical Review, 2003);

- Bromley, JS; Corsairs and Navies, 1600-1760; (Continnuum-3PL, 1987);

- Douglas, Hugh; John Ker, of Kersland; 1673-1726; (Oxford DNB, 2008);

- Hooke, Nathaniel; Secret History Of Colonel Hoocke's Negotiations In Scotland In Favour Of The Pretender In 1707: Including The Original Letters And Papers Which Passed Versailles And St. Germains; (Nabu, 2011 edition);

- Hopkins, Paul; Buchan, Thomas; 1641-1724; (Oxford DNB, 2004);

- Lenman, Bruce; The Jacobite Risings in Britain, 1689–1746; (Methuen Publishing, 1984);

- Lord, Evelyn; The Stuarts' Secret Army; (Pearson, 2004);

- Macinnes, AI; Jacobitism; (History Today, 1984);

- Owen, John Hely; War at Sea Under Queen Anne 1702-1708; (Cambridge University Press, 1938, 2010 ed);

- Sinclair-Stevenson, Christopher; The Jacobite Expedition of 1708; (History Today, April 1971);

- Szechi, Daniel; The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688–1788; (Manchester University Press, 1994).

- Whatley, Christopher; Scottish Society, 1707-1830: Beyond Jacobitism, Towards Industrialisation; (Manchester University Press, 2011);

.svg.png)