Taal Volcano

Taal Volcano (Filipino: Bulkang Taal, IPA: [taʔal]; Spanish: Volcán Taal) is a large caldera filled by Taal Lake on Luzon island in the Philippines,[1] and is in the province of Batangas. Taal Volcano is the second most active volcano in the Philippines, with 33 recorded historical eruptions, all of which were concentrated on Volcano Island, near the middle of Taal Lake. The caldera was formed by prehistoric eruptions between 140,000 and 5,380 BP.[2][3]

| Taal Volcano | |

|---|---|

| Bulkang Taal | |

Aerial photo of Volcano Island within Taal Volcano, taken in 2012. North is to the right-hand side. | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 311 m (1,020 ft) [1] |

| Coordinates | 14°0′36″N 120°59′51″E |

| Geography | |

.svg.png) Taal Volcano Location in the Philippines | |

| Location | Talisay and San Nicolas, Batangas, Philippines |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Caldera[1] |

| Volcanic arc/belt | Luzon Volcanic Arc |

| Last eruption | January 12, 2020 |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Daang Kastila (Spanish Trail) |

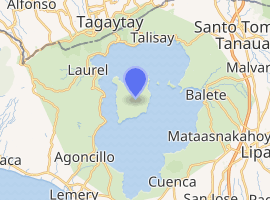

An interactive map of Taal Volcano | |

Viewed from the Tagaytay Ridge in Cavite, Taal Volcano and Lake presents one of the most picturesque and attractive views in the Philippines.[4] It is located about 50 kilometers (31 mi) south of the capital of the country, the city of Manila. The main crater of Taal Volcano originally had a lake until the explosive 2020 eruption expelled its water; the lake reformed within months in the rainy climate after activity ceased.

The volcano has had several violent eruptions in the past, causing loss of life on the island and the populated areas surrounding the lake, with the death toll estimated at about 6,000. Because of its proximity to populated areas and its eruptive history, the volcano was designated a Decade Volcano, worthy of close study to prevent future natural disasters. All volcanoes of the Philippines are part of the Pacific Ring of Fire.

Etymology

Taal Volcano was also called Bombou in 1821.[5]

Geography

.svg.png)

Taal Volcano and Lake are wholly located in the province of Batangas. The northern half of Volcano Island falls under the jurisdiction of the lake shore town of Talisay, and the southern half to San Nicolas. The other communities that encircle Taal Lake include the cities of Tanauan and Lipa, and the municipalities of Talisay, Laurel, Agoncillo, Santa Teresita, San Nicolas, Alitagtag, Cuenca, Balete, and Mataasnakahoy.[6]

Permanent settlement on the island is prohibited by the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS), declaring the whole Volcano Island as a high-risk area and a Permanent Danger Zone (PDZ).[7] Despite the warnings, some families remained settled on the island, risking their lives, earning a living by fishing and farming crops from the rich volcanic soil.[8][9][10][11]

The Main Crater Lake on Volcano Island is the largest lake on an island in a lake on an island in the world. Moreover, this lake used to contain Vulcan Point, a small rocky island inside the lake. After the 2020 eruption, the Main Crater Lake have disappeared due to volcanic activity.[12] However the Main Crater Lake returned by March 2020.[13]

Geological history

Taal Volcano is part of a chain of volcanoes along the western side of the edge of the island of Luzon, which were formed by the subduction of the Eurasian Plate underneath the Philippine Mobile Belt. Taal Lake lies within a 25–30 km (16–19 mi) caldera formed by explosive eruptions between 140,000 and 5,380 BP.[2] Each of these eruptions created extensive ignimbrite deposits, reaching as far away as where Manila stands today.[14]

Since the formation of the caldera, subsequent eruptions have created a volcanic island within the caldera, known as Volcano Island. This 5-kilometre (3.1 mi) island covers an area of about 23 square kilometres (8.9 sq mi) with the center of the island occupied by the 2-kilometre (1.2 mi) Main Crater with a single crater lake formed from the 1911 eruption. The island consists of different overlapping cones and craters of which forty-seven have been identified. Twenty six of these are tuff cones, five are cinder cones and four are maars.[15]

Eruption history

Pre-20th century

There have been 42 recorded eruptions at Taal from 1572 to 1977. The first eruption of which there is any record occurred in 1572, the year the Augustinian friars founded the town of Taal on the shores of the lake (on what is now San Nicolas, Batangas). In 1591, another mild eruption took place, featuring great masses of smoke issuing forth from the crater. From 1605 to 1611, the volcano displayed such great activity that Father Tomas de Abreu had a huge cross of anubing wood erected on the brink of the crater.[16][17]

Between 1707 and 1731, the center of activity shifted from the Main Crater to other parts of Volcano Island. The eruptions of 1707 and 1715 occurred in Binintiang Malaki (giant leg) crater (the cinder cone visible from Tagaytay Ridge), accompanied by thunder and lightning. Minor eruptions also emanated from the Binintiang Munti crater on the westernmost tip of the island in 1709 and 1729. A more violent event happened on 24 Sept. 1716, when the whole southeastern portion of the crater of (Calauit), opposite Mount Macolod, was blown out. Father Manuel de Arce noted the 1716 eruption "killed all the fishes...as if they had been cooked, since the water had been heated to a degree that it appeared to have been taken from a boiling caldron." The 1731 eruption off Pira-Piraso, or the eastern tip of the island, created a new island.[18][17]

Activity returned to the Main Crater on 11 Aug. 1749, and it was remembered for being particularly violent (VEI = 4), with eruptions continuing until 1753. Then came the great 200-day eruption of 1754,[15][16]Taal Volcano's greatest recorded eruption, which lasted from 15 May to 12 Dec. The eruption caused the relocation of the towns of Tanauan, Taal, Lipa and Sala. The Pansipit River was blocked, causing the water level in the lake to rise. Father Bencuchillo stated that of Taal, "nothing was left...except the walls of the church and convent...everything was buried beneath a layer of stones, mud, and ashes."[18][17]

Taal remained quiet for 54 years except for a minor eruption in 1790. Not until March 1808 did another big eruption occur. While this outbreak was not as violent as the one in 1754, the immediate vicinity was covered with ashes to a depth of 84 centimetres (33 in). It brought great changes in the interior of the crater, according to chroniclers of that time. "Before, the bottom looked very deep and seemed unfathomable, but at the bottom, a liquid mass was seen in continual ebullition. After the eruption, the crater had widened and the pond within it had been reduced to one-third and the rest of the crater floor was higher and dry enough to walk over it. The height of the crater walls has diminished and near the center of the new crater floor, a little hill that continually emitted smoke. On its sides were several wells, one of which was especially remarkable for its size."[18]

On July 19, 1874, an eruption of gases and ashes killed all the livestock on the island. From November 12–15, 1878, ashes ejected by the volcano covered the entire island. Another eruption took place in 1904, which formed a new outlet in the southeastern wall of the principal crater. As of 12 January 2020, the last eruption from the Main Crater was in 1911, which obliterated the crater floor creating the present lake. In 1965, a huge explosion sliced off a huge part of the island, moving activity to a new eruption center, Mount Tabaro.[15]

20th century

1911 eruption

One of the more devastating eruptions of Taal occurred in January 1911. During the night of the 27th of that month, the seismographs at the Manila Observatory commenced to register frequent disturbances, which were at first of insignificant importance, but increased rapidly in frequency and intensity. The total recorded shocks on that day numbered 26. During the 28th there were recorded 217 distinct shocks, of which 135 were microseismic, while 10 were quite severe. The frequent and increasingly strong earthquakes caused much alarm at Manila, but the observatory staff was soon able to locate their epicenter in the region of Taal Volcano and assured the public that Manila was in no danger, as Taal is distant from it some 60 km (37 mi) away.[19]

In Manila, in the early hours of 30 January 1911, people were awakened by what they at first perceived as loud thunder. The illusion was heightened when great lightning streaks were seen to illuminate the southern skies. Those who investigated further, however, soon learned the truth. A huge, fan-shaped cloud of what looked like black smoke ascended to great heights. It was crisscrossed with a brilliant electrical display, which the people of Manila perceived as lightning. This cloud finally shot up in the air, spread, then dissipated, and this marked the culmination of the eruption, at about 2:30 a.m.[16]

On Volcano Island, the destruction was complete. It seems that when the black, fan-shaped cloud spread, it created a blast downward that forced hot steam and gases down the slopes of the crater, accompanied by a shower of hot mud and sand. Many trees had the bark shredded and cut away from the surface by the hot sand and mud blast that accompanied the explosion, and contributed so much to the loss of life and destruction of property. The fact that practically all the vegetation was bent downward, away from the crater, proved that there must have been a very strong blast down the outside slopes of the cone. Very little vegetation was actually burned or even scorched.[16] Six hours after the explosion, dust from the crater was noticeable in Manila as it settled on furniture and other polished surfaces. The solid matter ejected had a volume of between seventy million and eighty million cubic metres (2.5×109 and 2.8×109 cubic feet) (VEI = 3.7). Ashes fell over an area of 2,000 square kilometres (770 square miles), although the area in which actual destruction took place measured only 230 square kilometres (89 sq mi).[16] The detonation from the explosion was heard over an area more than 1,000 kilometres (600 mi) in diameter.[19]

Death toll

The eruption claimed a reported 1,100 lives and injured 199, although it is known that more perished than the official records show. The seven barangays that existed on the island previous to the eruption were completely wiped out. Post mortem examination of the victims seemed to show that practically all had died of scalding by hot steam or hot mud, or both. The devastating effects of the blast reached the west shore of the lake, where a number of villages were also destroyed. Cattle to the number of 702 were killed and 543 nipa houses destroyed. Crops suffered from the deposit of ashes that fell to a depth of almost half an inch in places near the shore of the lake.

Effect on the Volcano Island

Volcano Island sank from 1 to 3 m (3 to 10 ft) as a result of the eruption. It was also found that the southern shore of Lake Taal sank in elevation from the eruption. No evidences of lava could be discovered anywhere, nor have geologists been able to trace any visible records of a lava flow having occurred at any time on the volcano back then. Another peculiarity of the geologic aspects of Taal is the fact that no sulphur has been found on the volcano. The yellow deposits and encrustations noticeable in the crater and its vicinity are iron salts, according to chemical analysis. A slight smell of sulfur was perceptible at the volcano, which came from the gases that escaped from the crater.[16]

Post-eruption crater changes

Great changes took place in the crater after the eruption. Before 1911, the crater floor was higher than Taal lake and had several separate openings in which there were lakes of different colors. There was a green lake, a yellow lake, a red lake and some holes filled with hot water from which steam issued. Many places were covered with a shaky crust of volcanic material, full of crevices, which was always hot and on which it was rather dangerous to walk. Immediately after the explosion, the vari-colored lakes had disappeared and in their place was one large lake, about ten feet below the level of the lake surrounding the island. The crater lake gradually rose until it is on a level with the water in Taal Lake. Popular opinions after the creation of the lake held that the presence of the water in the crater has a tendency to cool off the material below and thus lessen the chances of an explosion or make the volcano extinct, but the preponderance of expert opinion was otherwise.[16](The subsequent eruption in 1965 and succeeding activities came from a new eruptive center, Mount Tabaro.)

Ten years after the eruption, no changes in the general outline of the island could be discerned at a distance. On the island, however, many changes were noted. The vegetation had increased; great stretches that were formerly barren and covered with white ashes and cinders became covered with vegetation.[16]

1965 to 1977 eruption

There was a period of activity from 1965 to 1977 with the area of activity concentrated in the vicinity of Mount Tabaro. The 1965 eruption was classified as phreatomagmatic,[15] generated by the interaction of magma with the lake water that produced the violent explosion that cut an embayment on Volcano Island. The eruption generated "cold" base surges[20] which travelled several kilometers across Lake Taal, devastating villages on the lake shore and, killing about a hundred people.

An American geologist who had witnessed an atomic bomb explosion as a soldier visited the volcano shortly after the 1965 eruption and recognised "base surge" (now called pyroclastic surge when relating to volcanoes[21]) as a process in volcanic eruption.[22]

Precursory signs were not interpreted correctly until after the eruption; the population of the island was evacuated only after the onset of the eruption.

After nine months of repose, Taal reactivated on July 5, 1966 with another phreatomagmatic eruption from Mount Tabaro, followed by another similar eruption on August 16, 1967. The Strombolian eruptions which started five months after on January 31, 1968 produced the first historical lava fountaining witnessed from Taal. Another Strombolian eruption followed a year later on October 29, 1969. The massive flows from the two eruptions eventually covered the bay created by the 1965 eruption, reaching the shore of Lake Taal. The last major activities on the volcano during this period were the phreatic eruptions of 1976 and 1977.[15]

21st century

Since the 1977 eruption, it had shown signs of unrest since 1991, with strong seismic activity and ground fracturing events, as well as the formation of small mud pots and mud geysers on parts of the island. The Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) regularly issued notices and warnings about current activity at Taal, including ongoing seismic unrest.[23]

- 2008

- August 28. PHIVOLCS notified the public and concerned authorities that the Taal seismic network recorded ten (10) volcanic earthquakes from 5:30 a.m. to 3 PM. Two (2) of these quakes that occurred at 12:33 and 12:46 PM, were both felt at intensity II by residents at barangay Pira-piraso. These quakes were accompanied by rumbling sounds. The events were located northeast of the volcano island near Daang Kastila area with depths of approximately 0.6 kilometers (0.37 mi) (12:33 PM) and 0.8 kilometers (0.50 mi) (12:46 PM).[24]

- 2009

- July 20. National Disaster Coordinating Council (NDCC) executive officer Glenn Rabonza warned that although there were no volcanic quakes detected at Taal since the detection of nine volcanic quakes from June 13 to July 19, and there had been no steaming activity monitored since last recorded on June 23, PHIVOLCS Alert stands at Level 1, warning that Taal's main crater is off-limits to the public because steam explosions may occur or high concentrations of toxic gases may accumulate.

- 2010

- June 8. PHIVOLCS raised the volcano status to Alert Level 2[25] (scale is 0–5, 0 referring to No Alert status), which indicates the volcano is undergoing magmatic intrusion which could eventually lead to an eruption. PHIVOLCS reminds the general public that the Main Crater remains off-limits because hazardous steam-driven explosions may occur, along with the possible build-up of toxic gases. Areas with hot ground and steam emission such as portions of the Daang Kastila Trail are considered hazardous.[26]

- May 11–24. Crater lake temperature increased by 2–3 °C (3.6–5.4 °F). The composition of Main Crater Lake water has shown above normal values of Mg/Cl, SO4/Cl and Total Dissolved Solids. There has been ground steaming accompanied by hissing sounds on the northern and northeast sides of the main crater.

- April 26. Volcanic seismicity had increased.

- 2011

- From April 9 to July 5,[27] Alert Level on Taal Volcano was raised from 1 to 2 for eleven weeks because of increased seismicity on Volcano Island. Frequency peaked to about 115 tremors on May 30 with maximum intensity at IV, accompanied by rumbling sounds. Magma was intruding towards the surface, as indicated by continuing high rates of CO2 emissions in the Main Crater Lake and sustained seismic activity. Field measurements on May 24 showed lake temperatures slightly increased, pH values slightly more acidic and water levels 4 cm (1.6 in) higher. A ground deformation survey conducted around the Volcano Island April 26 to May 3 showed that the volcano edifice inflated slightly relative to the April 5-11 survey.[28]

- 2019

- Alert Level 1 was raised on the volcano because of frequent volcanic activities since March.[29] Based on the 24-hour monitoring of the Taal Volcano’s seismic network, 57 volcanic earthquakes were observed from the morning of November 11 to the morning of November 12.

2020

- The volcano erupted again on the afternoon of January 12, 2020, 43 years after the 1977 eruption, with the alert level of the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology escalating from Alert Level 2 to Alert Level 4.[30] It was an eruption from the main crater on Volcano Island. The eruption spewed ashes to Calabarzon, Metro Manila, some parts of Central Luzon and Pangasinan in Ilocos Region, which cancelled classes, work schedules, and flights.[31][32] Ashfalls and volcanic thunderstorms were reported, and forced evacuations were made.[33][34] There were also warnings of possible volcanic tsunami.[35] The volcano produced volcanic lightning above its crater with ash clouds.[36] The eruption progressed into magmatic eruption characterized by lava fountain with thunder and lightning.[37] By January 26, 2020, PHIVOLCS observed an inconsistent, but decreasing volcanic activity in Taal, prompting the agency to downgrade its warning to Alert Level 3.[38] On February 14, 2020 PHIVOLCS downgraded the volcano's warning to Alert Level 2, due to consistent decreased volcanic activity.[39][40]. A total of 39 people perished in the eruption, mostly because of either refusing to leave their homes, or from health-related problems during the evacuation.[41]

Activity monitoring

Alert Levels

PHIVOLCS maintains a distinct Alert Level system for six volcanoes in the Philippines including Taal. There are six levels, numbered 0 to 5.[42]

| Alert Level | Criteria | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Background, quiet | No eruption in foreseeable future. |

| 1 | Low level seismicity, fumarolic, other activity | Magmatic, tectonic or hydrothermal disturbance; no eruption imminent. |

| 2 | Low to moderate level of seismicity, persistence of local but unfelt earthquakes. Ground deformation measurements above baseline levels. Increased water and/or ground probe hole temperatures, increased bubbling at Crater Lake. |

|

| 3 | Relatively high unrest manifested by seismic swarms including increasing occurrence of low frequency earthquakes and/or harmonic tremor (some events felt). Sudden or increasing changes in temperature or bubbling activity or radon gas emission or crater lake pH. Bulging of the edifice and fissuring may accompany seismicity. |

|

| 4 | Intense unrest, continuing seismic swarms, including harmonic tremor and/or “low frequency earthquakes” which are usually felt, profuse steaming along existing and perhaps new vents and fissures. | Hazardous eruption is possible within days. |

| 5 | Base surges accompanied by eruption columns or lava fountaining or lava flows. | Hazardous eruption in progress. Extreme hazards to communities west of the volcano and ashfalls on downwind sectors. |

Eruption precursors at Taal

- Increase in frequency of volcanic quakes with occasional felt events accompanied by rumbling sounds

- On the Main Crater Lake, changes in the water temperature, level, and bubbling or boiling activity on the lake. Before the 1965 eruption began, the lake's temperature rose to about 15 °C (27 °F) degrees above normal.[43] However, with some eruptions there is no reported increase in the lake's temperature.

- Development of new or reactivation of old thermal areas like fumaroles, geysers or mudpots

- Ground inflation or ground fissuring.

- Increase in temperature of ground probe holes on monitoring stations.

- Strong sulfuric odor or irritating fumes similar to rotten eggs.

- Fish killed and drying up of vegetation.[2]

Other possible precursors

Volcanologists measuring the concentration of radon gas in the soil on Volcano island measured an anomalous increase of the radon concentration by a factor of six in October 1994. This increase was followed 22 days later by the magnitude 7.1 Mindoro earthquake on November 15, centered about 50 kilometres (31 miles) south of Taal, off the coast of Luzon.

A typhoon had passed through the area a few days before the radon spike was measured, but when Typhoon Angela, one of the most powerful to strike the area in ten years, crossed Luzon on almost the same track a year later, no radon spike was measured. Therefore, typhoons were ruled out as the cause, and there is strong evidence that the radon originated in the stress accumulation preceding the earthquake.[44]

See also

- List of active volcanoes in the Philippines

- List of inactive volcanoes in the Philippines

- List of potentially active volcanoes in the Philippines

- List of protected areas of the Philippines

- Bauan, Batangas

References

- "Taal". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- "Taal Volcano", PHIVOLCS, retrieved on 2012-12-03 (archived from the original on 2008-09-12)

- Delos Reyes, Perla J.; Bornas, Ma. Antonia V.; Dominey-Howes, Dale; Pidlaoan, Abigail C.; Magill, Christina R.; Solidum, Jr. , Renato U. (February 1, 2018). "A synthesis and review of historical eruptions at Taal Volcano, Southern Luzon, Philippines". Earth-Science Reviews. 177: 565–588. Bibcode:2018ESRv..177..565D. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.11.014. ISSN 0012-8252.

- Herre, Albert W.; "The Fisheries of Lake Taal, Luzon and Lake Naujan", Philippine Journal of Science, Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 287–303, 1927

- Roberts, Edmund (1837). Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 60. Archived from the original on April 16, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- (2011) "The Province map" Archived August 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Provincial Government of Batangas Web Site

- "NDCC Orders Close Watch on Mayon, Taal Volcanoes". GMA News Online. July 21, 2009. Archived from the original on June 17, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- kostito (December 13, 2009); "Photo – Taal Volcano Island" Archived December 14, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Panoramio, retrieved on March 26, 2011

- mharada (February 2, 2008); "Photo – Calauit, eastern shore of Volcano Island" Archived December 14, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Panoramio, retrieved on March 26, 2011

- vanpoperynghe (November 8, 2006); "Photo – Le Volcan Taal 13" Archived December 14, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Panoramio, retrieved on March 26, 2011

- Anuar T (March 15, 2010); "Photo – Buco, Volcano Island. Sundown" Archived December 14, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Panoramio, retrieved on March 26, 2011

- Amos, Jonathan (January 16, 2020). "Taal volcano lake all but gone in eruption". BBC News. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- "An Ash-Damaged Island in the Philippines". Earth Observatory. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Lowry, A.R.; Hamburger, M.W.; Meertens, C.M.; Ramos, E.G. (2001). "GPS monitoring of crustal deformation at Taal Volcano, Philippines". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 105 (1–2): 35–47. Bibcode:2001JVGR..105...35L. doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(00)00238-9.

- Taal Flyer, Philippine institute of Volcanology and Seismology, retrieved on 2010-11-27

- Lyons, Norbert. "Taal, One of the World's Great Volcanoes", American Chamber of Commerce Journal, Philippine Islands, p. 7

- Hargrove, Thomas (1991). The Mysteries of Taal: A Philippine volcano and lake, her sea life and lost towns. Manila: Bookmark Publishing. pp. 24–34, 145–148. ISBN 9715690467.

- Knittel, Ulrich (March 18, 1999). "History of Taal's activity to 1911 as described by Fr. Saderra Maso". Saderra Maso: Historical Taal. Institut für Mineralogie und Lagerstättenlehre. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- Worcester, Dean C.; "Taal Volcano and its Recent Destructive Eruption", National Geographic, Vol. XXIII, No. 4, p. 313

- Pyroclastic Flow and Pyroclastic Surges Archived 2011-06-12 at the Wayback Machine, Cascades Volcanic Observatory Web Site, retrieved on 2010-11-28

- Becker, Robert John; and Becker, Barbara (1998); Volcanoes, J.H. Freeman and Company, New York, p. 133, ISBN 0-7167-2440-5

- Miller, C. Dan (1989); "Potential Hazards from Future Volcanic Eruptions in California" Archived 2015-03-22 at the Wayback Machine : Glossary of Selected Volcanic Terms, USGS Bulletin 1847, retrieved on 2013-11-04

- "Alert level 2 raised at Taal volcano". The Philippine Star. June 9, 2010. Archived from the original on September 6, 2012. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- "Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology". Archived from the original on 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2008-11-30.

- "Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology". Archived from the original on 2010-06-11. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- 6,000 Taal villagers told to move out Archived 2010-06-12 at the Wayback Machine Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2010-06-09

- "Taal Volcano Bulletin 09 April 20117:00 A.M." Archived 28 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine, PHIVOLCS, retrieved on 2012-12-15

- Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (28 May 2011). "Taal Volcano Bulletin". PHIVOLCS Website. Department of Science and Technology. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- "Phivolcs puts Taal Volcano under Alert Level 1". Manila Bulletin. 12 November 2019. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "Alert Level 3 raised as Taal volcano manifests steam-driven explosion". Manila Bulletin. 12 January 2020. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "List: Class suspensions due to Taal Volcano eruption". Inquirer.net. 12 January 2020. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Taal eruption puts NAIA flights on hold". GMA News. 12 January 2020. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Alert Level 4 raised over Taal Volcano". GMA News Online. Archived from the original on 2020-01-12. Retrieved 2020-01-12.

- Acosta, Renzo. "Taal Volcano now on Alert Level 4: 'Hazardous eruption imminent'". newsinfo.inquirer.net. Archived from the original on 2020-01-13. Retrieved 2020-01-12.

- "Alert level 4 raised over Taal, volcanic tsunami possible: PHIVOLCS". ABS-CBN News. Archived from the original on 2020-01-14. Retrieved 2020-01-16.

- Santolo, Alessandra Scotto di (12 January 2020). "Philippines volcano eruption: Terrifying video of Taal volcano producing lightning strikes". Express.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Philippine Taal volcano begins spewing lava". BBC News. January 13, 2020. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020 – via www.bbc.com.

- Colcol, Erwin (January 26, 2020). "PHIVOLCS lowers Taal Volcano's status to Alert Level 2". GMA News. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- Magsino, Dona (February 14, 2020). "PHIVOLCS lowers Taal Volcano's status to Alert Level 2". GMA News. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- "Taal Volcano status lowered to Alert Level 2". CNN Philippines. February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- Recuenco, Aaron (February 2, 2020). "39 deaths recorded during Taal Volcano's eruption". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- "Taal Volcano Alert Signals". Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. 8 August 2018. Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- Moxham, Robert M. (1967); "Changes in Surface Temperature at Taal Volcano, Philippines 1965–1966" Archived 2018-06-05 at the Wayback Machine, SpringerLink, retrieved on 2013-02-13

- Richon, Patrick; Sabroux, Jean-Christophe; Halbwachs, Michel; Vandemeulebrouck, Jean; Poussielgue, Nicolas; Tabbagh, Jeanne; Punongbayan, Raymundo S. (2003); Radon anomaly in the soil of Taal volcano, the Philippines: A likely precursor of the M 7.1 Mindoro earthquake (1994), Geophysical Research Letters, Volume 30, Issue 9, pp. 1481–1484

![]()

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Taal Volcano. |

- "Taal Volcano". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- Taal Volcano Eruptions 1572–1911 from RWTH Aachen University Web Site

- Taal Volcano Eruptions 1600–2010 from Google

- Live-Stream: Taal Volcano