Sierra Nevada (U.S.)

The Sierra Nevada (/siˌɛrə nɪˈvædə, -ˈvɑːdə/, Spanish: [ˈsjera neˈβaða], snowy range[6]) is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primarily in Nevada. The Sierra Nevada is part of the American Cordillera, a chain of mountain ranges that consists of an almost continuous sequence of such ranges that form the western "backbone" of North America, Central America, South America and Antarctica.

| Sierra Nevada | |

|---|---|

The Sierra's Mills Creek cirque (center) is on the west side of the Sierra Crest, south of Mono Lake (top, blue). | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Mount Whitney |

| Elevation | 14,505 ft (4,421 m) [1] |

| Coordinates | 36°34′43″N 118°17′31″W |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 400 mi (640 km) north-south from Fredonyer Pass to Tehachapi Pass [2] |

| Width | 65 mi (105 km) [3] |

| Area | 24,370 sq mi (63,100 km2) [4] |

| Naming | |

| Etymology | 1777: Spanish for "snowy mountain range" |

| Nickname | the Sierra, the High Sierra, Range of Light (1894, John Muir)[5] |

| Geography | |

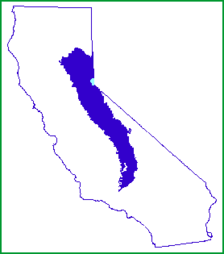

Position of Sierra Nevada inside California

| |

| Country | United States |

| States | California and Nevada |

| Range coordinates | 37°43′51″N 119°34′22″W |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Mesozoic |

| Type of rock | batholith and igneous |

The Sierra runs 400 miles (640 km) north-to-south, and is approximately 70 miles (110 km) across east-to-west. Notable Sierra features include the General Sherman (tree), the largest tree in the world by volume; Lake Tahoe, the largest alpine lake in North America; Mount Whitney at 14,505 ft (4,421 m),[1] the highest point in the contiguous United States; and Yosemite Valley sculpted by glaciers from one-hundred-million-year-old granite, containing high waterfalls. The Sierra is home to three national parks, twenty wilderness areas, and two national monuments. These areas include Yosemite, Sequoia, and Kings Canyon National Parks; and Devils Postpile National Monument.

The character of the range is shaped by its geology and ecology. More than one hundred million years ago during the Nevadan orogeny, granite formed deep underground. The range started to uplift four million years ago, and erosion by glaciers exposed the granite and formed the light-colored mountains and cliffs that make up the range. The uplift caused a wide range of elevations and climates in the Sierra Nevada, which are reflected by the presence of five life zones (areas with similar plant and animal communities). Uplift continues due to faulting caused by tectonic forces, creating spectacular fault block escarpments along the eastern edge of the southern Sierra.

The Sierra Nevada has a significant history. The California Gold Rush occurred in the western foothills from 1848 through 1855. Due to inaccessibility, the range was not fully explored until 1912.[7]:81

Geography

The Sierra Nevada lies in Central and Eastern California, with a very small but historically important spur extending into Nevada. West-to-east, the Sierra Nevada's elevation increases gradually from 1,000 feet (300 m) in the Central Valley to heights of about 14,000 feet (4,300 m) at its crest 50–75 miles (80–121 km) to the east. The east slope forms the steep Sierra Escarpment. Unlike its surroundings, the range receives a substantial amount of snowfall and precipitation due to orographic lift.

Setting

The Sierra Nevada's irregular northern boundary stretches from the Susan River[8] and Fredonyer Pass[9] to the North Fork Feather River. It represents where the granitic bedrock of the Sierra Nevada dives below the southern extent of Cenozoic igneous surface rock from the Cascade Range.[10] It is bounded on the west by California's Central Valley, on the east by the Basin and Range Province , and on the southeast by the Mojave Desert. The southern boundary is at Tehachapi Pass.[2]

Physiographically, the Sierra is a section of the Cascade–Sierra Mountains province, which in turn is part of the larger Pacific Mountain System physiographic division. The California Geological Survey states that "the northern Sierra boundary is marked where bedrock disappears under the Cenozoic volcanic cover of the Cascade Range."[11]

Watersheds

The range is drained on its western slope by the Central Valley watershed, which discharges into the Pacific Ocean at San Francisco. The northern third of the western Sierra is part of the Sacramento River watershed (including the Feather, Yuba, and American River tributaries), and the middle third is drained by the San Joaquin River (including the Mokelumne, Stanislaus, Tuolumne, and Merced River tributaries). The southern third of the range is drained by the Kings, Kaweah, Tule, and Kern rivers, which flow into the endorheic basin of Tulare Lake, which rarely overflows into the San Joaquin during wet years.

The eastern slope watershed of the Sierra is much narrower; its rivers flow out into the endorheic Great Basin of eastern California and western Nevada. From north to south, the Susan River flows into intermittent Honey Lake, the Truckee River flows from Lake Tahoe into Pyramid Lake, the Carson River runs into Carson Sink, the Walker River into Walker Lake; Rush, Lee Vining and Mill Creeks flow into Mono Lake; and the Owens River into dry Owens Lake. Although none of the eastern rivers reach the sea, many of the streams from Mono Lake southwards are diverted into the Los Angeles Aqueduct which provides water to Southern California.

Elevation

The height of the mountains in the Sierra Nevada increases gradually from north to south. Between Fredonyer Pass and Lake Tahoe, the peaks range from 5,000 feet (1,500 m) to more than 9,000 feet (2,700 m). The crest near Lake Tahoe is roughly 9,000 feet (2,700 m) high, with several peaks approaching the height of Freel Peak (10,881 ft or 3,317 m). Farther south, the highest peak in Yosemite National Park is Mount Lyell (13,120 ft or 3,999 m). The Sierra rises to almost 14,000 feet (4,300 m) with Mount Humphreys near Bishop, California. Finally, near Lone Pine, Mount Whitney is at 14,505 feet (4,421 m), the highest point in the contiguous United States.

South of Mount Whitney, the elevation of the range quickly dwindles. The crest elevation is almost 10,000 feet (3,000 m) near Lake Isabella, but south of the lake, the peaks reach only a modest 8,000 feet (2,400 m).[12]

Notable features

There are several notable geographical features in the Sierra Nevada:

- Lake Tahoe is a large, clear freshwater lake in the northern Sierra Nevada, with an elevation of 6,225 ft (1,897 m) and an area of 191 sq mi (490 km2).[13] Lake Tahoe lies between the main Sierra and the Carson Range, a spur of the Sierra.[13]

- Hetch Hetchy Valley, Yosemite Valley, Kings Canyon, and Kern Canyon are examples of many glacially-scoured canyons on the west side of the Sierra.

- Yosemite National Park is filled with notable features such as waterfalls, granite domes, high mountains, lakes, and meadows.

- Groves of giant sequoias Sequoiadendron giganteum occur along a narrow band of altitude on the western side of the Sierra Nevada. Giant sequoias are the largest trees in the world.[14]

- Two of the largest rivers in California, which form the Central Valley and drain into San Francisco Bay, derive most of their flow from the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada. The northern of the two is the Sacramento River (which also drains the adjacent Cascade Range and Klamath Range); the southern one is the San Joaquin River.

Communities

Communities in the Sierra Nevada include Paradise, South Lake Tahoe, Truckee, Grass Valley, Mammoth Lakes, Sonora, Nevada City, Placerville, Portola, Auburn, Colfax and Kennedy Meadows.

Protected areas

Much of the Sierra Nevada consists of federal lands and is either protected from development or strictly managed. The three National Parks (Yosemite, Kings Canyon, Sequoia), two national monuments (Devils Postpile, Giant Sequoia), and 26 wilderness areas lie within the Sierra. These areas protect 15.4% of the Sierra's 63,118 km2 (24,370 sq mi) from logging and grazing.[4]

The United States Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management currently control 52% of the land in the Sierra Nevada.[4] Logging and grazing are generally allowed on land controlled by these agencies, under federal regulations that balance recreation and development on the land.

The California Bighorn Sheep Zoological Area near Mount Williamson in the southern Sierra was established to protect the endangered Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep. Starting in 1981, hikers were unable to enter the Area from May 15 through December 15, in order to protect the sheep. As of 2010, the restriction has been lifted and access to the Area is open for the whole year.[15]

Geologic history

The earliest rocks in the Sierra Nevada are metamorphic roof pendants of Paleozoic age, the oldest being metasedimentary rocks from the Cambrian in the Mount Morrison region.[16] These dark-colored hornfels, slates, marbles, and schists are found in the western foothills (notably around Coarsegold, west of the Tehachapi Pass) and east of the Sierra Crest.[17] The earliest granite of the Sierra started to form in the Triassic period. This granite is mostly found east of the crest and north of 37.2°N.[18] In the Triassic and into the Jurassic, an island arc collided with the west coast of North America and raised a chain of volcanoes, in an event called the Nevadan orogeny.[19] Nearly all subaerial Sierran Arc volcanoes have since disappeared; their remains were redeposited during the Great Valley Sequence and the subsequent Cenozoic filling of the Great Valley, which is the source of much of the sedimentary rock in California.

In the Cretaceous, a subduction zone formed at the edge of the continent.[20] This means that an oceanic plate started to dive beneath the North American plate. Magma formed through the subduction of the ancient Farallon Plate rose in plumes (plutons) deep underground, their combined mass forming what is called the Sierra Nevada batholith. These plutons formed at various times, from 115 Ma to 87 Ma.[21] The earlier plutons formed in the western half of the Sierra, while the later plutons formed in the eastern half of the Sierra.[18] By 66 Ma, the proto-Sierra Nevada had been worn down to a range of rolling low mountains, a few thousand feet high.

Twenty million years ago, crustal extension associated with the Basin and Range Province caused extensive volcanism in the Sierra.[22] About 10 Ma, the Sierra Nevada started to form when a block of crust between the Coast Range and the Basin and Range Province started to tilt to the west[23] as heat from the Basin and Range extension thinned the eastern part of the block, making it more buoyant than the western portion of the block. Rivers started cutting deep canyons on both sides of the range. Lava filled some of these canyons, which have subsequently eroded leaving table mountains that follow the old river channels.[24]

About 2.5 Ma, the Earth's climate cooled, and ice ages started. Glaciers carved out characteristic U-shaped canyons throughout the Sierra. The combination of river and glacier erosion exposed the uppermost portions of the plutons emplaced millions of years before, leaving only a remnant of metamorphic rock on top of some Sierra peaks.

Uplift of the Sierra Nevada continues today, especially along its eastern side. This uplift causes large earthquakes, such as the Lone Pine earthquake of 1872.[25]

Climate and meteorology

The climate of the Sierra Nevada is influenced by the Mediterranean climate of California. During the fall, winter and spring, precipitation in the Sierra ranges from 20 to 80 in (510 to 2,030 mm) where it occurs mostly as snow above 6,000 ft (1,800 m). Precipitation is highest on the central and northern portions of the western slope between 5,000 and 8,000 feet (1,500 and 2,400 m) elevation, due to orographic lift.[21]:69 Above 8,000 feet (2,400 m), precipitation diminishes on the western slope up to the crest, since most of the precipitation has been wrung out at lower elevations. Most parts of the range east of the crest are in a rain shadow, and receive less than 25 inches of precipitation per year.[26] While most summer days are dry, afternoon thunderstorms are common, particularly during the North American Monsoon in mid and late summer. Some of these summer thunderstorms drop over an inch of rain in a short period, and the lightning can start fires. Summer high temperatures average 42–90 °F (6–32 °C). Winters are comparatively mild, and the temperature is usually only just low enough to sustain a heavy snowpack. For example, Tuolumne Meadows, at 8,600 feet (2,600 m) elevation, has winter daily highs about 40 °F (4 °C) with daily lows about 10 °F (−12 °C).[27] The growing season lasts 20 to 230 days, strongly dependent on elevation.[28] The highest elevations of the Sierra have an alpine climate.

The Sierra Nevada snowpack is the major source of water and a significant source of electric power generation in California.[29] Many reservoirs were constructed in the canyons of the Sierra throughout the 20th century, Several major aqueducts serving both agriculture and urban areas distribute Sierra water throughout the state. However, the Sierra casts a rain shadow, which greatly affects the climate and ecology of the central Great Basin. This rain shadow is largely responsible for Nevada being the driest state in the United States.[30]

Precipitation varies substantially from year to year. It is not uncommon for some years to receive precipitation totals far above or below normal.

The height of the range and the steepness of the Sierra Escarpment, particularly at the southern end of the range, produces a wind phenomenon known as the "Sierra Rotor". This is a horizontal rotation of the atmosphere just east of the crest of the Sierra, set in motion as an effect of strong westerly winds.[31]

Because of the large number of airplanes that have crashed in the Sierra Nevada, primarily due to the complex weather and atmospheric conditions such as downdrafts and microbursts caused by geography there, a portion of the area, a triangle whose vertices are Reno, Nevada; Fresno, California; and Las Vegas, Nevada, has been dubbed the "Nevada Triangle", in reference to the Bermuda Triangle. Some counts put the number of crashes in the triangle at 2,000,[32] including millionaire and record-breaking flyer Steve Fossett. Hypotheses that the crashes are related in some way to the United States Air Force's Area 51, or to the activities of extra-terrestrial aliens, have no evidence to support them.[33][34]

Ecology

The Sierra Nevada is divided into a number of biotic zones, each of which is defined by its climate and supports a number of interdependent species.[21] Life in the higher elevation zones adapted to colder weather, and to most of the precipitation falling as snow. The rain shadow of the Sierra causes the eastern slope to be warmer and drier: each life zone is higher in the east.[21] A list of biotic zones, and corresponding elevations, is presented below:

- The western foothill zone, 1,000–2,500 ft (300–760 m),[21]:92 with grassland, oak-grass savanna and chaparral-oak woodland.[28] North of Sequoia National Park, Gray pine (also known as digger pine) is intermixed with the oak woodland.[21]:95

- The Pinyon pine-Juniper woodland, 5,000–7,000 ft (1,500–2,100 m) east side only.[21]:92

- The Sierra Nevada lower montane forest (indicator species: Ponderosa pine, Jeffrey pine), 2,500–7,000 ft (760–2,130 m) west side, 7,000–9,000 ft (2,100–2,700 m) east side.[21]:92 This biotic zone is notable for containing giant sequoia.

- The Sierra Nevada upper montane forest (indicator species: Lodgepole pine, Red fir) 7,000–9,000 ft (2,100–2,700 m) west side, 9,000–10,500 ft (2,700–3,200 m) east side.[21]:92

- The Sierra Nevada subalpine zone (indicator species: Whitebark pine)[35] 9,000–10,500 ft (2,700–3,200 m) west side, 10,500–11,500 ft (3,200–3,500 m) east side[21]:92

- The alpine region at greater than 10,500 ft (3,200 m), and greater than 11,500 ft (3,500 m) east side.[21]:92

History

Native Americans

Archaeological excavations placed Martis people of Paleo-Indians in northcentral Sierra Nevada during the period of 3,000 BCE to 500 CE. The earliest identified sustaining indigenous people in the Sierra Nevada were the Northern Paiute tribes on the east side, with the Mono tribe and Sierra Miwok tribe on the western side, and the Kawaiisu and Tübatulabal tribes in the southern Sierra. Today, some historic intertribal trade route trails over mountain passes are known artifact locations, such as Duck Pass with its obsidian arrowheads. The California and Sierra Native American tribes were predominantly peaceful, with occasional territorial disputes between the Paiute and Sierra Miwok tribes in the mountains.[36] Washo and Maidu were also in this area prior to the era of European exploration and displacement.[37][38]

Etymology

Used in 1542 by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo to describe a Pacific Coast Range (Santa Cruz Mountains), the term "sierra nevada" was a general identification of less familiar ranges toward the interior.[41] In 1776, Pedro Font's map applied the name to the range currently known as the Sierra Nevada.[42]

The literal translation is "snowy mountains", from sierra "a range of hills", 1610s, from Spanish sierra "jagged mountain range", lit. "saw", from Latin serra "a saw"; and from fem. of Spanish nevado "snowy".[43][44]

Initial European-American exploration

American exploration of the mountain range started in 1827. Although prior to the 1820s there were Spanish missions, pueblos (towns), presidios (forts), and ranchos along the coast of California, no Spanish explorers visited the Sierra Nevada.[45] The first Americans to visit the mountains were amongst a group led by fur trapper Jedediah Smith, crossing north of the Yosemite area in May 1827, at Ebbetts Pass.[45]

In 1833, a subgroup of the Bonneville Expedition led by Joseph Reddeford Walker was sent westward to find an overland route to California. Eventually the party discovered a route along the Humboldt River across present-day Nevada, ascending the Sierra Nevada, starting near present-day Bridgeport and descending between the Tuolumne and Merced River drainage. The group may have been the first non-indigenous people to see Yosemite Valley.[46] The Walker Party probably visited either the Tuolumne or Merced Groves of giant sequoia, becoming the first non-indigenous people to see the giant trees,[45] but journals relating to the Walker party were destroyed in 1839, in a print shop fire in Philadelphia.[47]

In the winter of 1844, Lt. John C. Frémont, accompanied by Kit Carson, was the first American to see Lake Tahoe. The Frémont party camped at 8,050 ft (2,450 m).[48]

Gold rush

The California Gold Rush began at Sutter's Mill, near Coloma, in the western foothills of the Sierra.[49] On January 24, 1848, James W. Marshall, a foreman working for Sacramento pioneer John Sutter, found shiny metal in the tailrace of a lumber mill Marshall was building for Sutter on the American River.[50] Rumors soon started to spread and were confirmed in March 1848 by San Francisco newspaper publisher and merchant Samuel Brannan. Brannan strode through the streets of San Francisco, holding aloft a vial of gold, shouting "Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!"[50]

On August 19, 1848, the New York Herald was the first major newspaper on the East Coast to report the discovery of gold. On December 5, 1848, President James Polk confirmed the discovery of gold in an address to Congress.[51]:80 Soon, waves of immigrants from around the world, later called the "forty-niners", invaded the Gold Country of California or "Mother Lode". Miners lived in tents, wood shanties, or deck cabins removed from abandoned ships.[52] Wherever gold was discovered, hundreds of miners would collaborate to put up a camp and stake their claims.

Because the gold in the California gravel beds was so richly concentrated, the early forty-niners simply panned for gold in California's rivers and streams.[53]:198–200 However, panning cannot take place on a large scale, and miners and groups of miners graduated to more complex placer mining. Groups of prospectors would divert the water from an entire river into a sluice alongside the river, and then dig for gold in the newly exposed river bottom.[54]:90

By 1853, most of the easily accessible gold had been collected, and attention turned to extracting gold from more difficult locations. Hydraulic mining was used on ancient gold-bearing gravel beds on hillsides and bluffs in the gold fields.[51]:89 In hydraulic mining, a high-pressure hose directed a powerful stream or jet of water at gold-bearing gravel beds. It is estimated that by the mid-1880s, 11 million ounces (340 t) of gold (worth approximately US$15 billion at December 2010 prices) had been recovered by "hydraulicking".[55] A byproduct of these extraction methods was that large amounts of gravel, silt, heavy metals, and other pollutants went into streams and rivers.[54]:32–36 As of 1999, many areas still bear the scars of hydraulic mining, since the resulting exposed earth and downstream gravel deposits do not support plant life.[54]:116–121

It is estimated that by 1855, at least 300,000 gold-seekers, merchants, and other immigrants had arrived in California from around the world.[51]:25 The huge numbers of newcomers brought by the Gold Rush drove Native Americans out of their traditional hunting, fishing and food-gathering areas. To protect their homes and livelihood, some Native Americans responded by attacking the miners, provoking counter-attacks on native villages. The Native Americans, out-gunned, were often slaughtered.[54]

Thorough exploration

The Gold Rush populated the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, but even by 1860, most of the Sierra was unexplored.[7][56] The state legislature authorized the California Geological Survey to officially explore the Sierra (and survey the rest of the state). Josiah Whitney was appointed to head the survey. Men of the survey, including William H. Brewer, Charles F. Hoffmann and Clarence King, explored the backcountry of what would become Yosemite National Park in 1863.[7] In 1864, they explored the area around Kings Canyon. In 1869, John Muir started his wanderings in the Sierra Nevada range,[57] and in 1871, King was the first to climb Mount Langley, mistakenly believing he had summited Mount Whitney, the highest peak in the range.[58] In 1873, Mount Whitney was climbed for the first time by 3 men from Lone Pine, CA on a fishing trip.[7] From 1892–7 Theodore Solomons made the first attempt to map a route along the crest of the Sierra.[7]

Other people finished exploring and mapping the Sierra. Bolton Coit Brown explored the Kings River watershed in 1895–1899. Joseph N. LeConte mapped the area around Yosemite National Park and what would become Kings Canyon National Park. James S. Hutchinson, a noted mountaineer, climbed the Palisades (1904) and Mount Humphreys (1905). By 1912, the USGS published a set of maps of the Sierra Nevada, and the era of exploration was over.[7]:81

Conservation

The tourism potential of the Sierra Nevada was recognized early in the European history of the range. Yosemite Valley was first protected by the federal government in 1864. The Valley and Mariposa Grove were ceded to California in 1866 and turned into a state park.[46] John Muir perceived overgrazing by sheep and logging of giant sequoia to be a problem in the Sierra. Muir successfully lobbied for the protection of the rest of Yosemite National Park: Congress created an Act to protect the park in 1890. The Valley and Mariposa Grove were added to the Park in 1906.[46] In the same year, Sequoia National Park was formed to protect the Giant Sequoia: all logging of the Sequoia ceased at that time.

In 1903, the city of San Francisco proposed building a hydroelectric dam to flood Hetch Hetchy Valley. The city and the Sierra Club argued over the dam for 10 years, until the U.S. Congress passed the Raker Act in 1913 and allowed dam building to proceed. O'Shaughnessy Dam was completed in 1923.[59][60]

Between 1912 and 1918, Congress debated three times to protect Lake Tahoe in a national park. None of these efforts succeeded, and after World War II, towns such as South Lake Tahoe grew around the shores of the lake. By 1980, the permanent population of the Lake Tahoe area grew to 50,000, while the summer population grew to 90,000.[61] The development around Lake Tahoe affected the clarity of the lake water. In order to preserve the lake's clarity, construction in the Tahoe basin is currently regulated by the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency.[62]

As the 20th century progressed, more of the Sierra became available for recreation; other forms of economic activity decreased. The John Muir Trail, a trail that followed the Sierra crest from Yosemite Valley to Mount Whitney, was funded in 1915 and finished in 1938.[63] Kings Canyon National Park was formed in 1940 to protect the deep canyon of the Kings River.

By 1964, the Wilderness Act protected portions of the Sierra as primitive areas where humans are simply temporary visitors. Gradually, 20 wilderness areas were established to protect scenic backcountry of the Sierra. These wilderness areas include the John Muir Wilderness (protecting the eastern slope of the Sierra and the area between Yosemite and Kings Canyon Parks), and wilderness within each of the National Parks. Because of the Wilderness Act and the rocky terrain in the area, plans to construct two trans-Sierra highways across this portion of the Sierra Escarpment, State Route 168[64] and State Route 190,[65] were abandoned; the two highways each remain split as discontiguous segments on either side of the Sierra.

The Sierra Nevada still faces a number of issues that threaten its conservation. Logging occurs on both private and public lands, including controversial clearcut methods and thinning logging on private and public lands.[66] Grazing occurs on private lands as well as on National Forest lands, which include Wilderness areas. Overgrazing can alter hydrologic processes and vegetation composition, remove vegetation that serves as food and habitat for native species, and contribute to sedimentation and pollution in waterways.[67] A recent increase in large wildfires like the Rim Fire in Yosemite National Park and the Stanislaus National Forest and the King Fire on the Eldorado National Forest, has prompted concerns.[66] A 2015 study indicated that the increase in fire risk in California may be attributable to human-induced climate change.[68] A study looking back over 8,000 years found that warmer climate periods experienced severe droughts and more stand-replacing fires and concluded that as climate is such a powerful influence on wildfires, trying to recreate presettlement forest structure is likely impossible in a warmer future.[69]

See also

- Bibliography of the Sierra Nevada

- List of Sierra Nevada road passes

- List of Sierra Nevada topics

References

- "Mount Whitney". NGS data sheet. U.S. National Geodetic Survey.

- "Sierra Nevada". Ecological Subregions of California. United States Forest Service. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010.

- "Sierra Nevada". SummitPost.org. Retrieved May 29, 2010.

- "The Sierra Nevada Region". USCB Biogeography lab. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011.

- Muir, John (1894). "Chapter 1: The Sierra Nevada". The Mountains of California. Retrieved May 29, 2010.

- Carlson, Helen S. (1976). Nevada Place Names: A Geographical Dictionary. University of Nevada Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-87417-094-8.

- Roper, Steve (1997). Sierra High Route: Traversing Timberline Country. The Mountaineers Press. ISBN 978-0-89886-506-6.

- "Subsection M261Eb: Fredonyer Butte – Grizzly Peak". Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- "Sierra Nevada". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

- "California Geomorphic Provinces" (PDF). California Geological Survey. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2004.

- "California Geologic Provinces" (PDF). California Geological Survey. p. 2. Note 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2016.

- "Google terrain map". Retrieved May 29, 2010.

- "Facts about Lake Tahoe". USGS. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- "The General Sherman Tree". U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on March 15, 2010.

- "Forest Service Proposes to Change Designation of Bighorn Sheep Zoological Areas". United States Forest Service. September 25, 2010.

- Stevens, CH; Greene, DC (2000). "Geology of Paleozoic rocks in eastern Sierra Nevada roof pendants, California". Geological Society of America. Field Guide 2.

- "Geology and Mineral Deposits of the Mount Morrison Quadrangle, Sierra Nevada, California" (PDF). United States Geological Survey.

- Unger, Tanya S. "Mesozoic Plutonism in the Sierra Nevada Batholith". Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- Shaffer, Jeffrey. "Evolution of the Yosemite Landscape – The Nevadan Orogeny". One Hundred Hikes in Yosemite. Archived from the original on April 24, 2011.

- Blakely, Ron. "Geologic History of Western US".

- Schoenherr, Allan A. (1995). A Natural History of California. UC Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06922-0.

- Joel Michaelsen. "Basin and Range (Transierra) Region Physical Geography". Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- Jayko, A.S. (October 18, 2009). "Miocene-Pliocene uplit rates of the Sierra Nevada, California". 2009 Portland GSA meeting.

- Romans, Brian (October 2010). "Inverted Martian Topography". Wired.

- "1872 Lone Pine Earthquake". Sierra Nevada Virtual Museum. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

Few people ever see a mountain range grow, but on March 26, 1872, the 300 residents of Lone Pine, California, did.

- "Average Annual Precipitation". Sierra Nevada Photos. Archived from the original on February 22, 2008. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- "Weather". Yosemite. National Park Service.

- "Chapter 33-Ecological subregions of the United States, Sierran Steppe - Mixed Forest - Coniferous Forest". United States Forest Service. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- "Water—Most of California's Water Comes from the Sierra Nevada" (PDF). Sierra Nevada Conservancy. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 18, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- "Climatology by state based on climate division data: 1971–2000". NOAA Earth Systems Research Laboratory.

- Grubišic, Vanda; Billings, Brian J. (2006). Sierra Rotors: A Comparative Study of Three Mountain Wave and Rotor Events (PDF). 12th Conference on Mountain Meteorology. American Meteorological Society.

- Schoenmann, Joe. "The Nevada Triangle: A Graveyard For Planes". knpr.org. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- Winter, Stuart (January 3, 2010). "Mystery of the Nevada Triangle". Sunday Express.

- Pupp, Martin (director) (December 1, 2014). The Missing Evidence: Nevada Triangle (TV series episode).

- Fites-Kauffman, J.; P. W. Rundel; N. Stephenson; D. A. Weixelman (2007). "Montane and subalpine vegetation of the Sierra Nevada and Cascade Ranges". In Barbour, M.G.; Keeler-Wolf, T.; Schoenherr, A.A. (eds.). Terrestrial vegetation of California (3rd ed.). Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press. pp. 460–501.

- Hoffmann, Charles F. (1868). "Notes on Hetch-Hetchy Valley". Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. 1 (3:5): 368–370. Archived from the original on May 9, 2011. Retrieved September 27, 2006.

- Drake, Bill (2000). "Ancient petroglyph makers of the Northern Sierra". sierrarockart.org. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008.

- "Prehistoric Context" (PDF). Idaho-Maryland Mine Project, Master Environmental Assessment. cityofgrassvalley.com. June 2006. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2010. Retrieved August 15, 2008.

- Farquhar, Francis P. (1926). "K". Place Names of the Sierra Nevada. San Francisco: Sierra Club. Archived from the original on March 13, 2006.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- The ship was named after Mount Kearsarge in New Hampshire, see "Kearsarge (BB-5)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command (NHHC). February 23, 2005. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- Farquhar, Francis P. (March 1925). "Exploration of the Sierra Nevada". California Historical Society Quarterly. 4 (1): 3–58. doi:10.2307/25177743. JSTOR 25177743. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011.

- Farquhar, Francis P. (1926). "S". Place Names of the Sierra Nevada. San Francisco: Sierra Club. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Sierra". Etymology Online.

- "Nevada". Etymology Online.

- Wuerthner, George (1994). Yosemite: A Visitors Companion. Stackpole Books. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0-8117-2598-9.

- Schaffer, Jeffrey P. (1999). Yosemite National Park: A Natural History Guide to Yosemite and Its Trails. Berkeley: Wilderness Press. ISBN 978-0-89997-244-2.

- Kiver, Eugene P.; Harris, David V. (1999). Geology of U.S. Parklands (5th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-33218-3.

- Frémont's "Long Camp". 2007 [1999]. Retrieved May 29, 2010.

- "California Historic Gold Mines" (PDF). State of California. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 14, 2006.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1889). History of California, Volume 23: 1843–1850. San Francisco: The History Company. pp. 32–34.

- Starr, Kevin (2005). California: a history. New York: The Modern Library.

- Holliday, J. S. (1999). Rush for riches; gold fever and the making of California. Oakland, California, Berkeley and Los Angeles: Oakland Museum of California and University of California Press. p. 60.

- Brands, H. W. (2003). The age of gold: the California Gold Rush and the new American dream. New York: Anchor (reprint ed.).

- Rawls, James J.; Orsi, Richard J., eds. (1999). A golden state: mining and economic development in Gold Rush California (California History Sesquicentennial Series, 2). Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- "Mining History and Geology of the Mother Lode". Archived from the original on December 3, 2006.

- Moore, James G. (2000). Exploring the Highest Sierra. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3703-6.

- Muir, John (1911). My First Summer in the Sierra. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-1-883011-24-6.

- Leonard, Brendan (n.d.). "Famous U.S. Summits: Mount Whitney, California". REI Co-op Journal. www.rei.com/blog: REI Co-op. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- Simpson, John W. (2005). Dam!: Water, Power, Politics, and Preservation in Hetch Hetchy and Yosemite National Park. ISBN 978-0-375-42231-7.

- Righter, Robert W. (2005). The Battle over Hetch Hetchy: America's Most Controversial Dam and the Birth of Modern Environmentalism. ISBN 978-0-19-531309-3.

- "Stream and Ground-Water Monitoring Program, Lake Tahoe Basin, Nevada and California". USGS. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- "Construction Monitoring". Tahoe Regional Planning Agency. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011.

- Starr, Walter A. (November 1947). "Trails". Sierra Club Bulletin. 32 (10).

- "State Route 168 Transportation Concept Report" (PDF). California Department of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 11, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- "State Route 190 Transportation Concept Report" (PDF). California Department of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 21, 2010. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- "Forest Issues - CSERC". CSERC. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- "2014 Grazing Report Released by CSERC - CSERC". CSERC. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- Yoon, Jin-Ho; Wang, S.-Y. Simon; Gillies, Robert R.; Hipps, Lawrence; Kravitz, Ben; Rasch, Philip J. (2015). "Extreme Fire Season in California: A Glimpse Into the Future?". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 96 (11): S5–S9. Bibcode:2015BAMS...96S...5Y. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-15-00114.1. ISSN 1520-0477.

- Pierce, Jennifer L.; Meyer, Grant A.; Timothy Jull, A. J. (November 4, 2004). "Fire-induced erosion and millennial-scale climate change in northern ponderosa pine forests". Nature. 432 (7013): 87–90. Bibcode:2004Natur.432...87P. doi:10.1038/nature03058. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 15525985.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1905 New International Encyclopedia article about Sierra Nevada (U.S.). |