Oregon Treaty

The Oregon Treaty[1] is a treaty between Great Britain and the United States that was signed on June 15, 1846, in Washington, D.C.. The treaty brought an end to the Oregon boundary dispute by settling competing American and British claims to the Oregon Country; the area had been jointly occupied by both Britain and the U.S. since the Treaty of 1818.[2]

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

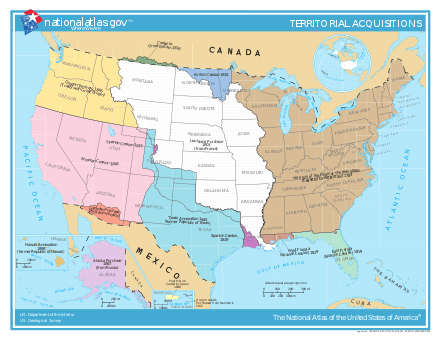

Map of the lands in dispute | |

| Type | bilateral treaty |

| Signed | 15 June 1846 |

| Location | Washington, D.C., United States |

| Original signatories | |

| Language | English |

Background

The Treaty of 1818 set the boundary between the United States and British North America along the 49th parallel of north latitude from Minnesota to the "Stony Mountains"[3] (now known as the Rocky Mountains). The region west of those mountains was known to the Americans as the Oregon Country and to the British as the Columbia Department or Columbia District of the Hudson's Bay Company. (Also included in the region was the southern portion of another fur district, New Caledonia.) The treaty provided for joint control of that land for ten years. Both countries could claim land and both were guaranteed free navigation throughout.

Joint control steadily grew less tolerable for both sides. After a British minister rejected U.S. Presidents James K. Polk and John Tyler offer to settle the boundary at the 49th parallel north, United States American Empire expansionists called for the annexation of the entire region up to Parallel 54°40′ north, the southern limit of Russian America as established by parallel treaties between the Russian Empire and the United States (1824) and Britain (1825). However, after the outbreak of the Mexican–American War in April 1846 diverted U.S. attention and military resources, a compromise was reached in the ongoing negotiations in Washington, D.C., and the matter was then settled by the Polk administration (to the dismay of its own party's hardliners) to avoid a two-war situation, and a third war with the formidable military strength of Great Britain in less than 70 years.[4]

Negotiations

The treaty was negotiated by U.S. Secretary of State James Buchanan, who later became president, and Richard Pakenham, British envoy to the United States and member of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom for Queen Victoria; the Earl of Aberdeen was at the time Foreign Secretary, and it was he who was responsible for it in Parliament.[5] The treaty was signed on June 15, 1846, ending the joint occupation with Great Britain and making most Oregonians below the 49th parallel American citizens.[6]

The Oregon Treaty set the U.S. and British North American border at the 49th parallel with the exception of Vancouver Island, which was retained in its entirety by the British. Vancouver Island, with all coastal islands, was constituted as the Colony of Vancouver Island in 1849. The U.S. portion of the region was organized as Oregon Territory on August 15, 1848, with Washington Territory being formed from it in 1853. The British portion remained unorganized until 1858, when the Colony of British Columbia was declared as a result of the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush and fears of the re-asserted American expansionist intentions. The two British colonies were amalgamated in 1866 as the United Colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia. When the Colony of British Columbia joined Canada in 1871, the 49th Parallel and marine boundaries established by the Oregon Treaty became the Canada–US border.

In order to ensure that Britain retained all of Vancouver Island and the southern Gulf Islands, it was agreed that the border would swing south around that area. Ownership of several channel islands, including the San Juan Islands remained in dispute. The San Juan Islands Pig War (1859) resulted; it lasted until 1872. At that time, arbitration began, with Wilhelm I as head of a three-man arbitration commission.[7] On October 21, 1872, the commission decided in favor of the United States, awarding the San Juan Islands to the U.S.[8]

Treaty definitions

The treaty defined the border in the Strait of Juan de Fuca through the major channel. The "major channel" was not defined, giving rise to further disputes in the San Juan Islands in 1859. Other provisions included:

- Navigation of "channel[s] and straits, south of the forty-ninth parallel of north latitude, remain free and open to both parties".

- The "Puget's Sound Agricultural Company" (a subsidiary of the Hudson's Bay Company) retains the right to their property north of the Columbia River, and shall be compensated for properties surrendered if required by the United States.

- The property rights of the Hudson's Bay Company and all British subjects south of the new boundary will be respected.[9]

Issues arising from treaty

Ambiguities in the wording of the Oregon Treaty regarding the route of the boundary, which was to follow "the deepest channel" out to the Strait of Juan de Fuca and beyond to the open ocean, resulted in the Pig War, another boundary dispute in 1859 over the San Juan Islands. The dispute was peacefully resolved after a decade of confrontation and military bluster during which the local British authorities consistently lobbied London to seize back the Puget Sound region entirely, as the Americans were busy elsewhere with the Civil War. The San Juans dispute was not resolved until 1872 when, pursuant to the 1871 Treaty of Washington, an arbitrator (William I, German Emperor) chose the American-preferred marine boundary via Haro Strait, to the west of the islands, over the British preference for Rosario Strait which lay to their east.

The treaty also had the unintended consequence of putting what became Point Roberts, Washington on the "wrong" side of the border. A peninsula, jutting south from Canada into Boundary Bay, was made by the agreement, as land south of the 49th parallel, a separate fragment of the United States.

According to American historian Thomas C. McClintock, the British public welcomed the treaty:

- Frederick Merk's statement that the "whole British press" greeted the news of the Senate's ratification of Lord Aberdeen's proposed treaty with "a sigh of relief" and "universal satisfaction" comes close to being accurate. The Whig, Tory, and independent newspapers agreed in their expressions of satisfaction with the treaty. Though a few newspapers had at least mild reservations, completely absent was the strong condemnation that had greeted the earlier Webster-Ashburton Treaty (which determined the northeast boundary between the United States and Canada). Lord Aberdeen had been determined to prevent such a response to the Oregon Treaty, and obviously he was extremely successful in doing so.[10]

See also

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Joseph Smith Harris' account of surveying the border

- Presidency of James K. Polk

- United Kingdom–United States relations

- Webster-Ashburton Treaty

References and footnotes

- officially titled the Treaty between Her Majesty and the United States of America, for the Settlement of the Oregon Boundary and styled in the United States as the Treaty with Great Britain, in Regard to Limits Westward of the Rocky Mountains, and also known as the Buchanan-Pakenham (or Packenham) Treaty or (sharing the name with several other unrelated treaties) the Treaty of Washington

- David M. Pletcher, The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War. (U of Missouri Press, 1973).

- "Convention of Commerce between His Majesty and the United States of America.—Signed at London, 20th October 1818". Canado-American Treaties. Université de Montréal. 2000. Archived from the original on April 11, 2009. Retrieved 2006-03-27.

- Donald A. Rakestraw, For Honor or Destiny: The Anglo-American Crisis over the Oregon Territory (Peter Lang Publishing, 1995)

- Churchill 1958

- Walker, Dale L. (1999). Bear Flag Rising: The Conquest of California, 1846. New York: Macmillan. p. 60. ISBN 0312866852.

- "The Pig War". San Juan Island National Historical Park. National Park Service. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- "Britain and the United States agree on the 49th parallel as the main Pacific Northwest boundary in the Treaty of Oregon on June 15, 1846". History Link. July 13, 2013. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- "Treaty between Her Majesty and the United States of America, for the Settlement of the Oregon Boundary". Canado-American Treaties. Université de Montréal. 1999. Archived from the original on November 13, 2009. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- Thomas C. McClintock, "British newspapers and the Oregon Treaty of 1846." Oregon Historical Quarterly,(2003) 94#1 pp 96-109 at p. 96. online

Bibliography

- Anderson, Stuart. "British Threats and the Settlement of the Oregon Boundary Dispute." Pacific Northwest Quarterly 66#4 (1975): 153-160. online

- Cramer, Richard S. "British magazines and the Oregon question." Pacific Historical Review 32.4 (1963): 369-382. online

- Dykstra, David L. The Shifting Balance of Power: American-British Diplomacy in North America, 1842-1848 (University Press of America, 1999).

- Jones, Wilbur D., and J. Chal Vinson. “British Preparedness and the Oregon Settlement.” Pacific Historical Review 22#4 (1953): 353-364. online

- Levirs, Franklin P. "The British attitude to the Oregon question, 1846." (Diss. University of British Columbia, 1931) online.

- Miles, Edwin A. “'Fifty-four Forty or Fight' – An American Political Legend.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 44#2 (1957): 291-309. online

- Merk, Frederick. “The British Corn Crisis of 1845-46 and the Oregon Treaty.” Agricultural History 8#3 (1934): 95-123.

- Merk, Frederick. “British Government Propaganda and the Oregon Treaty.” American Historical Review 40#1 (1934): 38-62 online

- Pletcher, David M. The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War. (U of Missouri Press, 1973), a standard scholarly history

- Rakestraw, Donald A. For Honor or Destiny: The Anglo-American Crisis over the Oregon Territory (Peter Lang Publishing, 1995), a standard scholarly history.

- Winther, Oscar Osburn. "The British in Oregon Country: A Triptych View." The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 58.4 (1967): 179-187. online