Shakespeare in performance

Thousands of performances of William Shakespeare's plays have been staged since the end of the 16th century. While Shakespeare was alive, many of his greatest plays were performed by the Lord Chamberlain's Men and King's Men acting companies at the Globe and Blackfriars Theatres.[1][2] Among the actors of these original performances were Richard Burbage (who played the title role in the first performances of Hamlet, Othello, Richard III and King Lear),[3] Richard Cowley, and William Kempe.

Shakespeare's plays continued to be staged after his death until the Interregnum (1642–1660), when most public stage performances were banned by the Puritan rulers. After the English Restoration, Shakespeare's plays were performed in playhouses, with elaborate scenery, and staged with music, dancing, thunder, lightning, wave machines, and fireworks. During this time the texts were "reformed" and "improved" for the stage, an undertaking which has seemed shockingly disrespectful to posterity.

Victorian productions of Shakespeare often sought pictorial effects in "authentic" historical costumes and sets. The staging of the reported sea fights and barge scene in Antony and Cleopatra was one spectacular example.[4] Such elaborate scenery for the frequently changing locations in Shakespeare's plays often led to a loss of pace. Towards the end of the 19th century, William Poel led a reaction against this heavy style. In a series of "Elizabethan" productions on a thrust stage, he paid fresh attention to the structure of the drama. In the early 20th century, Harley Granville-Barker directed quarto and folio texts with few cuts,[5] while Edward Gordon Craig and others called for abstract staging. Both approaches have influenced the variety of Shakespearean production styles seen today.[6]

Performances during Shakespeare's lifetime

The troupe for which Shakespeare wrote his earliest plays is not known with certainty; the title page of the 1594 edition of Titus Andronicus reveals that it had been acted by three different companies.[7] After the plagues of 1592–93, Shakespeare's plays were performed by the Lord Chamberlain's Men, a new company of which Shakespeare was a founding member, at The Theatre and the Curtain in Shoreditch, north of the Thames.[8] Londoners flocked there to see the first part of Henry IV, Leonard Digges recalling, "Let but Falstaff come, Hal, Poins, the rest ... and you scarce shall have a room".[9] When the landlord of the Theatre announced that he would not renew the company's lease, they pulled the playhouse down and used the timbers to construct the Globe Theatre, the first London playhouse built by actors for actors, on the south bank of the Thames at Southwark.[10] The Globe opened in autumn 1599, with Julius Caesar one of the first plays staged. Most of Shakespeare's greatest post-1599 plays were written for the Globe, including Hamlet, Othello and King Lear.[11]

The Globe, like London's other open-roofed public theatres, employed a thrust-stage, covered by a cloth canopy. A two-storey facade at the rear of the stage hid the tiring house and, through windows near the top of the facade, opportunities for balcony scenes such as the one in Romeo and Juliet. Doors at the bottom of the facade may have been used for discovery scenes like that at the end of The Tempest. A trap door in the stage itself could be used for stage business, like some of that involving the ghost in Hamlet. This trapdoor area was called "hell", as the canopy above was called "heaven"

Less is known about other features of staging and production. Stage props seem to have been minimal, although costuming was as elaborate as was feasible. The "two hours' traffic" mentioned in the prologue to Romeo and Juliet was not fanciful; the city government's hostility meant that performances were officially limited to that length of time. Though it is not known how seriously companies took such injunctions, it seems likely either that plays were performed at near-breakneck speed or that the play-texts now extant were cut for performance, or both.

The other main theatre where Shakespeare's original plays were performed was the second Blackfriars Theatre, an indoor theatre built by James Burbage, father of Richard Burbage, and impresario of the Lord Chamberlain's Men. However, neighborhood protests kept Burbage from using the theater for the Lord Chamberlain's Men performances for a number of years. After the Lord Chamberlain's Men were renamed the King's Men in 1603, they entered a special relationship with the new court of King James. Performance records are patchy, but it is known that the King's Men performed seven of Shakespeare's plays at court between 1 November 1604 and 31 October 1605, including two performances of The Merchant of Venice.[12] In 1608 the King's Men (as the company was then known) took possession of the Blackfriars Theatre. After 1608, the troupe performed at the indoor Blackfriars Theatre during the winter and the Globe during the summer.[13] The indoor setting, combined with the Jacobean vogue for lavishly staged masques, created new conditions for performance which enabled Shakespeare to introduce more elaborate stage devices. In Cymbeline, for example, Jupiter descends "in thunder and lightning, sitting upon an eagle: he throws a thunderbolt. The ghosts fall on their knees."[14] Plays produced at the indoor theater presumably also made greater use of sound effects and music.

A fragment of the naval captain William Keeling's diary survives, in which he details his crew's shipboard performances of Hamlet (off the coast of Sierra Leone, 5 September 1607, and at Socotra, 31 March 1608),[15] and Richard II (Sierra Leone, 30 September 1607).[15] For a time after its discovery, the fragment was suspected of being a forgery, but is now generally accepted as genuine.[16] These are the first recorded amateur performances of any Shakespeare plays.[15]

On 29 June 1613, the Globe Theatre went up in flames during a performance of Henry VIII. A theatrical cannon, set off during the performance, misfired, igniting the wooden beams and thatching. According to one of the few surviving documents of the event, no one was hurt except a man who put out his burning breeches with a bottle of ale.[17] The event pinpoints the date of a Shakespeare play with rare precision. Sir Henry Wotton recorded that the play "was set forth with many extraordinary circumstances of pomp and ceremony".[18] The theatre was rebuilt but, like all the other theatres in London, the Globe was closed down by the Puritans in 1642.

The actors in Shakespeare's company included Richard Burbage, Will Kempe, Henry Condell and John Heminges. Burbage played the leading role in the first performances of many of Shakespeare's plays, including Richard III, Hamlet, Othello, and King Lear.[19] The popular comic actor Will Kempe played Peter in Romeo and Juliet and Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing, among other parts. He was replaced around the turn of the 16th century by Robert Armin, who played roles such as Touchstone in As You Like It and the fool in King Lear.[20] Little is certainly known about acting styles. Critics praised the best actors for their naturalness. Scorn was heaped on ranters and on those who "tore a passion to tatters", as Hamlet has it. Also with Hamlet, playwrights complain of clowns who improvise on stage (modern critics often blame Kemp in particular in this regard). In the older tradition of comedy which reached its apex with Richard Tarlton, clowns, often the main draw of a troupe, were responsible for creating comic by-play. By the Jacobean era, that type of humor had been supplanted by verbal wit.

Interregnum and Restoration performances

Shakespeare's plays continued to be staged after his death until the Interregnum (1642–1660), when most public stage performances were banned by the Puritan rulers. While denied the use of the stage, costumes and scenery, actors still managed to ply their trade by performing "drolls" or short pieces of larger plays that usually ended with some type of jig. Shakespeare was among the many playwrights whose works were plundered for these scenes. Among the drolls taken from Shakespeare were Bottom the Weaver (Bottom's scenes from A Midsummer Night's Dream)[21] and The Grave-makers (the gravedigger's scene from Hamlet).[22]

At the Restoration in 1660, Shakespeare's plays were divided between the two newly licensed companies: the King's Company of Thomas Killigrew and the Duke's Men of William Davenant. The licensing system prevailed for two centuries; from 1660 to 1843, only two main companies regularly presented Shakespeare in London. Davenant, who had known early-Stuart actors such as John Lowin and Joseph Taylor, was the main figure establishing some continuity with earlier traditions; his advice to his actors is thus of interest as possible reflections of original practices.

On the whole, though, innovation was the order of the day for Restoration companies. John Downes reports that the King's Men initially included some Caroline actors; however, the forced break of the Interregnum divided both companies from the past. Restoration actors performed on proscenium stages, often in the evening, between six and nine. Set-design and props became more elaborate and variable. Perhaps most noticeably, boy players were replaced by actresses. The audiences of comparatively expensive indoor theaters were richer, better educated, and more homogeneous than the diverse, often unruly crowds at the Globe. Davenant's company began at the Salisbury Court Theatre, then moved to the theater at Lincoln's Inn Fields, and finally settled in the Dorset Garden Theatre. Killigrew began at Gibbon's Tennis Court before settling into Christopher Wren's new theatre in Drury Lane. Patrons of both companies expected fare quite different from what had pleased Elizabethans. For tragedy, their tastes ran to heroic drama; for comedy, to the comedy of manners. Though they liked Shakespeare, they seem to have wished his plays to conform to these preferences.

Restoration writers obliged them by adapting Shakespeare's plays freely. Writers such as William Davenant and Nahum Tate rewrote some of Shakespeare's plays to suit the tastes of the day, which favoured the courtly comedy of Beaumont and Fletcher and the neo-classical rules of drama.[23] In 1681, Tate provided The History of King Lear, a modified version of Shakespeare's original tragedy with a happy ending. According to Stanley Wells, Tate's version "supplanted Shakespeare's play in every performance given from 1681 to 1838,"[24] when William Charles Macready played Lear from a shortened and rearranged version of Shakespeare's text.[25] "Twas my good fortune", Tate said, "to light on one expedient to rectify what was wanting in the regularity and probability of the tale, which was to run through the whole a love betwixt Edgar and Cordelia that never changed words with each other in the original".[26]

Tate's Lear remains famous as an example of an ill-conceived adaptation arising from insensitivity to Shakespeare's tragic vision. Tate's genius was not in language – many of his interpolated lines don't even scan – but in structure; his Lear begins brilliantly with the Edmund the Bastard's first attention-grabbing speech, and ends with Lear's heroic saving of Cordelia in the prison and a restoration of justice to the throne. Tate's worldview, and that of the theatrical world that embraced (and demanded) his "happy ending" versions of the Bard's tragic works (such as King Lear and Romeo and Juliet) for over a century, arose from a profoundly different sense of morality in society and of the role that theatre and art should play within that society. Tate's versions of Shakespeare see the responsibility of theatre as a transformative agent for positive change by holding a moral mirror up to our baser instincts. Tate's versions of what we now consider some of the Bard's greatest works dominated the stage throughout the 18th century precisely because the Ages of Enlightenment and Reason found Shakespeare's "tragic vision" immoral, and his tragic works unstageable. Tate is seldom performed today, though in 1985, the Riverside Shakespeare Company mounted a successful production of The History of King Lear at The Shakespeare Center, heralded by some as a "Lear for the Age of Ronald Reagan."[27]

Perhaps a more typical example of the purpose of Restoration revisions is Davenant's The Law Against Lovers, a 1662 comedy combining the main plot of Measure for Measure with subplot of Much Ado About Nothing. The result is a snapshot of Restoration comic tastes. Beatrice and Benedick are brought in to parallel Claudio and Hero; the emphasis throughout is on witty conversation, and Shakespeare's thematic focus on lust is steadily downplayed. The play ends with three marriages: Benedick's to Beatrice, Claudio's to Hero, and Isabella's to an Angelo whose attempt on Isabella's virtue was a ploy. Davenant wrote many of the bridging scenes and recast much of Shakespeare's verse as heroic couplets.

A final feature of Restoration stagecraft impacted productions of Shakespeare. The taste for opera that the exiles had developed in France made its mark on Shakespeare as well. Davenant and John Dryden worked The Tempest into an opera, The Tempest, or The Enchanted Island; their work featured a sister for Miranda, a man, Hippolito, who has never seen a woman, and another paired marriage at the end. It also featured many songs, a spectacular shipwreck scene, and a masque of flying cupids. Other of Shakespeare's works given operatic treatment included A Midsummer Night's Dream (as The Fairy-Queen in 1692) and Charles Gildon's Measure for Measure (by way of an elaborate masque.)

However ill-guided such revisions may seem now, they made sense to the period's dramatists and audiences. The dramatists approached Shakespeare not as bardolators, but as theater professionals. Unlike Beaumont and Fletcher, whose "plays are now the most pleasant and frequent entertainments of the stage", according to Dryden in 1668, "two of theirs being acted through the year for one of Shakespeare's or Jonson's",[28] Shakespeare appeared to them to have become dated. Yet almost universally, they saw him as worth updating. Though most of these revised pieces failed on stage, many remained current on stage for decades; Thomas Otway's Roman adaptation of Romeo and Juliet, for example, seems to have driven Shakespeare's original from the stage between 1680 and 1744. It was in large part the revised Shakespeare that took the lead place in the repertory in the early 18th century, while Beaumont and Fletcher's share steadily declined.[29]

18th century

The 18th century witnessed three major changes in the production of Shakespeare's plays. In England, the development of the star system transformed both acting and production; at the end of the century, the Romantic revolution touched acting as it touched all the arts. At the same time, actors and producers began to return to Shakespeare's texts, slowly weeding out the Restoration revisions. Finally, by the end of the century Shakespeare's plays had been established as part of the repertory outside of Great Britain: not only in the United States but in many European countries.

Britain

In the 18th century, Shakespeare dominated the London stage, while Shakespeare productions turned increasingly into the creation of star turns for star actors. After the Licensing Act of 1737, one fourth of the plays performed were by Shakespeare, and on at least two occasions rival London playhouses staged the very same Shakespeare play at the same time (Romeo and Juliet in 1755 and King Lear the next year) and still commanded audiences. This occasion was a striking example of the growing prominence of Shakespeare stars in the theatrical culture, the big attraction being the competition and rivalry between the male leads at Covent Garden and Drury Lane, Spranger Barry and David Garrick. In the 1740s, Charles Macklin, in roles such as Malvolio and Shylock, and David Garrick, who won fame as Richard III in 1741, helped make Shakespeare truly popular.[30] Garrick went on to produce 26 of the plays at Drury Lane Theatre between 1747 and 1776, and he held a great Shakespeare Jubilee at Stratford in 1769.[31] He freely adapted Shakespeare's work, however, saying of Hamlet: "I had sworn I would not leave the stage till I had rescued that noble play from all the rubbish of the fifth act. I have brought it forth without the grave-digger's trick, Osrick, & the fencing match."[32] Apparently no incongruity was perceived in having Barry and Garrick, in their late thirties, play adolescent Romeo one season and geriatric King Lear the next. 18th century notions of verisimilitude did not usually require an actor to be physically appropriate for a role, a fact epitomized by a 1744 production of Romeo and Juliet in which Theophilus Cibber, then forty, played Romeo to the Juliet of his teenaged daughter Jennie.

Elsewhere in Europe

Some of Shakespeare's work was performed in continental Europe even during his lifetime; Ludwig Tieck pointed out German versions of Hamlet and other plays, of uncertain provenance, but certainly quite old.[33] but it was not until after the middle of the next century that Shakespeare appeared regularly on German stages.[34] In Germany Lessing compared Shakespeare to German folk literature. Goethe organised a Shakespeare jubilee in Frankfurt in 1771, stating that the dramatist had shown that the Aristotelian unities were "as oppressive as a prison" and were "burdensome fetters on our imagination". Herder likewise proclaimed that reading Shakespeare's work opens "leaves from the book of events, of providence, of the world, blowing in the sands of time".[35] This claim that Shakespeare's work breaks though all creative boundaries to reveal a chaotic, teeming, contradictory world became characteristic of Romantic criticism, later being expressed by Victor Hugo in the preface to his play Cromwell, in which he lauded Shakespeare as an artist of the grotesque, a genre in which the tragic, absurd, trivial and serious were inseparably intertwined.[36]

19th century

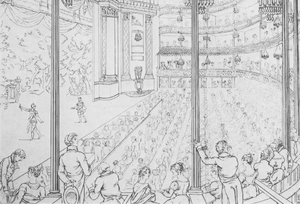

Theatres and theatrical scenery became ever more elaborate in the 19th century, and the acting editions used were progressively cut and restructured to emphasize more and more the soliloquies and the stars, at the expense of pace and action.[37] Performances were further slowed by the need for frequent pauses to change the scenery, creating a perceived need for even more cuts in order to keep performance length within tolerable limits; it became a generally accepted maxim that Shakespeare's plays were too long to be performed without substantial cuts. The platform, or apron, stage, on which actors of the 17th century would come forward for audience contact, was gone, and the actors stayed permanently behind the fourth wall or proscenium arch, further separated from the audience by the orchestra (see image at right).

Victorian productions of Shakespeare often sought pictorial effects in "authentic" historical costumes and sets. The staging of the reported sea fights and barge scene in Antony and Cleopatra was one spectacular example.[4] Too often, the result was a loss of pace. Towards the end of the century, William Poel led a reaction against this heavy style. In a series of "Elizabethan" productions on a thrust stage, he paid fresh attention to the structure of the drama.

Through the 19th century, a roll call of legendary actors' names all but drown out the plays in which they appear: Sarah Siddons (1755–1831), John Philip Kemble (1757–1823), Henry Irving (1838–1905), and Ellen Terry (1847–1928). To be a star of the legitimate drama came to mean being first and foremost a "great Shakespeare actor", with a famous interpretation of, for men, Hamlet, and for women, Lady Macbeth, and especially with a striking delivery of the great soliloquies. The acme of spectacle, star, and soliloquy of Shakespeare performance came with the reign of actor-manager Henry Irving and his co-star Ellen Terry in their elaborately staged productions, often with orchestral incidental music, at the Lyceum Theatre, London from 1878 to 1902. At the same time, a revolutionary return to the roots of Shakespeare's original texts, and to the platform stage, absence of scenery, and fluid scene changes of the Elizabethan theatre, was being effected by William Poel's Elizabethan Stage Society.[38]

20th century

In the early 20th century, Harley Granville-Barker directed quarto and folio texts with few cuts,[5] while Edward Gordon Craig and others called for abstract staging. Both approaches have influenced the variety of Shakespearean production styles seen today.[6]

The 20th century also saw a multiplicity of visual interpretations of Shakespeare's plays.

Gordon Craig's design for Hamlet in 1911 was groundbreaking in its Cubist influence. Craig defined space with simple flats: monochrome canvases stretched on wooden frames, which were hinged together to be self-supporting. Though the construction of these flats was not original, its application to Shakespeare was completely new. The flats could be aligned in many configurations and provided a technique of simulating architectural or abstract lithic structures out of supplies and methods common to any theater in Europe or the Americas.

The second major shift of 20th-century scenography of Shakespeare was in Barry Vincent Jackson's 1923 production of Cymbeline at the Birmingham Rep. This production was groundbreaking because it reintroduced the idea of modern dress back into Shakespeare. It was not the first modern-dress production since there were a few minor examples before World War I, but Cymbeline was the first to call attention to the device in a blatant way. Iachimo was costumed in evening dress for the wager, the court was in military uniforms, and the disguised Imogen in knickerbockers and cap. It was for this production that critics invented the catch phrase "Shakespeare in plus-fours".[39] The experiment was moderately successful, and the director, H.K. Ayliff, two years later staged Hamlet in modern dress. These productions paved the way for the modern-dress Shakespearean productions that we are familiar with today.

In 1936, Orson Welles was hired by the Federal Theatre Project to direct a groundbreaking production of Macbeth in Harlem with an all African American cast. The production became known as the Voodoo Macbeth, as Welles changed the setting to a 19th-century Haiti run by an evil king thoroughly controlled by African magic.[40] Initially hostile, the black community took to the production thoroughly, ensuring full houses for ten weeks at the Lafayette Theatre and prompting a small Broadway success and a national tour.[41]

Other notable productions of the 20th century that follow this trend of relocating Shakespeare's plays are H.K. Ayliff's Macbeth of 1928 set on the battlefields of World War I, Welles' Julius Caesar of 1937 based on the Nazi rallies at Nuremberg, and Thacker's Coriolanus of 1994 costumed in the manner of the French Revolution.[42]

In 1978, a deconstructive version of The Taming of the Shrew was performed at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre.[43] The main character walked through the audience toward the stage, acting drunk and shouting sexist comments before he proceeded to tear down (i.e., deconstruct) the scenery. Even after press coverage, some audience members still fled from the performance, thinking they were witnessing a real assault.[43]

21st century

The Royal Shakespeare Company in the UK has produced two major Shakespeare festivals in the twenty-first century. The first was the Complete Works (RSC festival) in 2006–2007, which staged productions of all of Shakespeare's plays and poems.[44] The second is the World Shakespeare Festival in 2012, which is part of the London 2012 Cultural Olympiad, and features nearly 70 productions involving thousands of performers from across the world.[45] More than half of these productions are part of the Globe to Globe Festival. Each of the productions in this festival has been reviewed by Shakespeare academics, theatre practitioners, and bloggers in a project called Year of Shakespeare.

In May 2009, Hamlet opened with Jude Law in the title role at the Donmar Warehouse West End season at Wyndham's. He was joined by Ron Cook, Peter Eyre, Gwilym Lee, John MacMillan, Kevin R McNally, Gugu Mbatha-Raw, Matt Ryan, Alex Waldmann and Penelope Wilton. The production officially opened on 3 June and ran through 22 August 2009.[46][47] The production was also mounted at Elsinore Castle in Denmark from 25–30 August 2009[48] and on Broadway at the Broadhurst Theatre in New York.

The Propeller company have taken all-male cast productions around the world.[49] Phyllida Lloyd has continually staged all-female cast versions of Shakespeare in London.[50][51][52]

Shakespeare on screen

More than 420 feature-length film versions of Shakespeare's plays have been produced since the early 20th century, making Shakespeare the most filmed author ever.[53] Some of the film adaptations, especially Hollywood movies marketed to teenage audiences, use his plots rather than his dialogue, while others are simply filmed versions of his plays.

Dress and design

For centuries there had been an accepted style of how Shakespeare was to be performed which was erroneously labeled "Elizabethan" but actually reflected a trend of design from a period shortly after Shakespeare's death. Shakespeare's performances were originally performed in contemporary dress. Actors were costumed in clothes that they might wear off the stage. This continued into the 18th century, the Georgian period, where costumes were the current fashionable dress. It was not until centuries after his death, primarily the 19th Century, that productions started looking back and tried to be "authentic" to a Shakespearean style. The Victorian era had a fascination with historical accuracy and this was adapted to the stage in order to appeal to the educated middle class. Charles Kean was particularly interested in historical context and spent many hours researching historical dress and setting for his productions. This faux-Shakespearean style was fixed until the 20th century. As of the twenty-first century, there are very few productions of Shakespeare, both on stage and on film, which are still performed in "authentic" period dress, while as late as 1990, virtually every true film version of a Shakespeare play was performed in correct period costume. The first film in English to break this pattern was 1995's Richard III which updated the setting to the 1930s but changed none of Shakespeare's dialogue.

See also

Notes

- Editor's Preface to A Midsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare, Simon and Schuster, 2004, p. xl

- Foakes, 6.

• Nagler, A.M (1958). Shakespeare's Stage. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 7. ISBN 0-300-02689-7.

• Shapiro, 131–32. - Ringler, William jr. "Shakespeare and His Actors: Some Remarks on King Lear" from Lear from Study to Stage: Essays in Criticism edited by James Ogden and Arthur Hawley Scouten, Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 1997, p. 127.

King,T.J. (Thomas J. King, Jr.) (1992). Casting Shakespeare's Plays; London actors and their roles 1590–1642, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-32785-7 (Paperback edition 2009, ISBN 0-521-10721-0) - Halpern (1997). Shakespeare Among the Moderns. New York: Cornell University Press, 64. ISBN 0-8014-8418-9.

- Griffiths, Trevor R (ed.) (1996). A Midsummer Night's Dream. William Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Introduction, 2, 38–39. ISBN 0-521-57565-6.

• Halpern, 64. - Bristol, Michael, and Kathleen McLuskie (eds.). Shakespeare and Modern Theatre: The Performance of Modernity. London; New York: Routledge; Introduction, 5–6. ISBN 0-415-21984-1.

- Wells, Oxford Shakespeare, xx.

- Wells, Oxford Shakespeare, xxi.

- Shapiro, 16.

- Foakes, R.A. (1990). "Playhouses and Players". In The Cambridge Companion to English Renaissance Drama. A.R. Braunmuller and Michael Hattaway (eds.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 6. ISBN 0-521-38662-4.

• Shapiro, 125–31. - Foakes, 6.

• Nagler, A.M. (1958). Shakespeare's Stage. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 7. ISBN 0-300-02689-7.

• Shapiro, 131–32.

• King, T.J. (Thomas J. King, Jr.) (1971). Shakespearean Staging, 1599–1642. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-80490-2. - Wells, Oxford Shakespeare, xxii.

- Foakes, 33.

- Ackroyd, 454.

• Holland, Peter (ed.) (2000). Cymbeline. London: Penguin; Introduction, xli. ISBN 0-14-071472-3. - Alan & Veronica Palmer, Who's Who in Shakespeare's England. Retrieved 29 May 2015

- Halliday, F.E. A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; pp. 262, 426–27.

- Globe Theatre Fire.

- Wells, Oxford Shakespeare, 1247.

- Ringler, William Jr. (1997)."Shakespeare and His Actors: Some Remarks on King Lear". In Lear from Study to Stage: Essays in Criticism. James Ogden and Arthur Hawley Scouten (eds.). New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 127. ISBN 0-8386-3690-X.

- Chambers, Vol 1: 341.

• Shapiro, 247–49. - Nettleton, 16.

- Arrowsmith, 72.

- Murray, Barbara A (2001). Restoration Shakespeare: Viewing the Voice. New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 50. ISBN 0-8386-3918-6.

• Griswold, Wendy (1986). Renaissance Revivals: City Comedy and Revenge Tragedy in the London Theatre, 1576–1980. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 115. ISBN 0-226-30923-1. - Stanley Wells, "Introduction" from King Lear, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 63.

- Wells, p. 69.

- From Tate's dedication to The History of King Lear. Quoted by Peter Womack (2002). "Secularizing King Lear: Shakespeare, Tate and the Sacred." In Shakespeare Survey 55: King Lear and its Afterlife. Peter Holland (ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 98. ISBN 0-521-81587-8.

- See Riverside Shakespeare Company.

- Dryden, Essay of Dramatick Poesie, The Critical and Miscellaneous Prose Works of John Dryden, Edmond Malone, ed. (London: Baldwin, 1800): 101.

- Sprague, 121.

- Uglow, Jenny (1997). Hogarth. London: Faber and Faber, 398. ISBN 0-571-19376-5.

- Martin, Peter (1995). Edmond Malone, Shakespearean Scholar: A Literary Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 27. ISBN 0-521-46030-1.

- Letter to Sir William Young, 10 January 1773. Quoted by Uglow, 473.

- Tieck, xiii.

- Pfister 49.

- Düntzer, 111.

- Cappon, 65.

- See, for example, the 19th century playwright W. S. Gilbert's essay, Unappreciated Shakespeare Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, from Foggerty's Fairy and Other Tales

- Glick, 15.

- Trewin, J.C. Shakespeare on the English Stage, 1900–1064. London, 1964.

- Ayanna Thompson (2011). Passing Strange: Shakespeare, Race, and Contemporary America. Oxford University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780195385854.

- Hill, 106.

- Jackson 345.

- Looking at Shakespeare: A Visual History of Twentieth-Century Performance by Dennis Kennedy, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 1–3.

- Cahiers Elisabéthains: A Biannual Journal of English Renaissance Studies, Special Issue 2007: The Royal Shakespeare Company Complete Works Festival, 2006–2007, Stratford-upon-Avon, Edited by Peter J. Smith and Janice Valls-Russell with Kath Bradley

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Mark Shenton, "Jude Law to Star in Donmar's Hamlet." The Stage. 10 September 2007. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

- "Cook, Eyre, Lee And More Join Jude Law In Grandage's HAMLET." broadwayworld.com. 4 February 2009. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- "Jude Law to play Hamlet at 'home' Kronborg Castle." The Daily Mirror. 10 July 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- Theatre programme, Everyman Cheltenham, June 2009.

- Michael Billington (10 January 2012). "Julius Caesar – review". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- "Henry IV". St Ann's Warehouse. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- Katie Van-Syckle (24 May 2016). "Phyllida Lloyd Reveals Challenges of Bringing All-Female 'Taming of the Shrew' to Central Park". Variety. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- Young, Mark (ed.). The Guinness Book of Records 1999, Bantam Books, 358; Voigts-Virchow, Eckart (2004), Janespotting and Beyond: British Heritage Retrovisions Since the Mid-1990s, Gunter Narr Verlag, 92.

Bibliography

- Arrowsmith, William Robson. Shakespeare's Editors and Commentators. London: J. Russell Smith, 1865.

- Cappon, Edward. Victor Hugo: A Memoir and a Study. Edinburgh: Blackwood, 1885.

- Dryden, John. The Critical and Miscellaneous Prose Works of John Dryden. Edmond Malone, editor. London: Baldwin, 1800.

- Düntzer, J.H.J., Life of Goethe. Thomas Lyster, translator. New York: Macmillan, 1884.

- Glick, Claris. "William Poel: His Theories and Influence." Shakespeare Quarterly 15 (1964).

- Hill, Erroll. Shakespeare in Sable. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1984.

- Houseman, John. Run-through: A Memoir. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1972.

- Jackson, Russell. "Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avon, 1994–5." Shakespeare Quarterly 46 (1995).

- Nettleton, George Henry. English Drama of the Restoration and Eighteenth Century (1642–1780). London: Macmillan, 1914.

- Pfister, Manfred. "Shakespeare and the European Canon." Shifting the Scene: Shakespeare in European Culture. Balz Engler and Ledina Lambert, eds. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 2004.

- Sprague, A.C. Beaumont and Fletcher on the Restoration Stage. New York: Benjamin Blom, 1954.

- Tieck, Ludwig. Alt-englischen drama. Berlin, 1811.

External links

- Shakespeare at the National Theatre, 1967–2012, compiled by Daniel Rosenthal, on Google Arts & Culture

.png)