King John (play)

The Life and Death of King John, a history play by William Shakespeare, dramatises the reign of John, King of England (ruled 1199–1216), son of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine and father of Henry III of England. It is believed to have been written in the mid-1590s but was not published until it appeared in the First Folio in 1623.[1]

Characters

|

|

| PLANTAGENET | CAPET | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Henry II K.England 1154–89 | Eleanor of Aquitaine | Louis VII K.France 1137–80 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Richard I K.England 1189–99 | Geoffrey | Lady Constance | KING JOHN K.England 1199–1216 | Eleanor Queen of Castile | Philip II K.France 1180–1223 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Philip Faulconbridge (‘The Bastard’) | Arthur | Henry III (‘Prince Henry’) K.England 1216–72 | Blanche of Castile | Louis VIII (‘The Dauphin’) K.France 1223–26 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Synopsis

King John receives an ambassador from France who demands with a threat of war that he renounce his throne in favour of his nephew, Arthur, whom the French King Philip believes to be the rightful heir to the throne.

John adjudicates an inheritance dispute between Robert Faulconbridge and his older brother Philip the Bastard, during which it becomes apparent that Philip is the illegitimate son of King Richard I. Queen Eleanor, mother to both Richard and John, recognises the family resemblance and suggests that he renounce his claim to the Falconbridge land in exchange for a knighthood. John knights Philip the Bastard under the name Richard.

In France, King Philip and his forces besiege the English-ruled town of Angiers, threatening attack unless its citizens support Arthur. Philip is supported by Austria, who is believed to have killed King Richard. The English contingent arrives; and then Eleanor trades insults with Constance, Arthur's mother. Kings Philip and John stake their claims in front of Angiers' citizens, but to no avail: their representative says that they will support the rightful king, whoever that turns out to be.

The French and English armies clash, but no clear victor emerges. Each army dispatches a herald claiming victory, but Angiers' citizens continue to refuse to recognize either claimant because neither army has proven victorious.

The Bastard proposes that England and France unite to punish the rebellious citizens of Angiers, at which point the citizens propose an alternative: Philip's son, Louis the Dauphin, should marry John's niece Blanche (a scheme that gives John a stronger claim to the throne) while Louis gains territory for France. Though a furious Constance accuses Philip of abandoning Arthur, Louis and Blanche are married.

Cardinal Pandolf arrives from Rome bearing a formal accusation that John has disobeyed the Pope and appointed an archbishop contrary to his desires. John refuses to recant, whereupon he is excommunicated. Pandolf pledges his support for Louis, though Philip is hesitant, having just established family ties with John. Pandolf brings him round by pointing out that his links to the church are older and firmer.

War breaks out; Austria is beheaded by the Bastard in revenge for his father's death; and both Angiers and Arthur are captured by the English. Eleanor is left in charge of English possessions in France, while the Bastard is sent to collect funds from English monasteries. John orders Hubert to kill Arthur. Pandolf suggests to Louis that he now has as strong a claim to the English throne as Arthur (and indeed John), and Louis agrees to invade England.

Hubert finds himself unable to kill Arthur. John's nobles urge Arthur's release. John agrees, but is wrong-footed by Hubert's announcement that Arthur is dead. The nobles, believing he was murdered, defect to Louis' side. Equally upsetting, and more heartbreaking to John, is the news of his mother's death, along with that of Lady Constance. The Bastard reports that the monasteries are unhappy about John's attempt to seize their gold. Hubert has a furious argument with John, during which he reveals that Arthur is still alive. John, delighted, sends him to report the news to the nobles.

Arthur dies jumping from a castle wall. (It is open to interpretation whether he deliberately kills himself or just makes a risky escape attempt.) The nobles believe he was murdered by John, and refuse to believe Hubert's entreaties. John attempts to make a deal with Pandolf, swearing allegiance to the Pope in exchange for Pandolf's negotiating with the French on his behalf. John orders the Bastard, one of his few remaining loyal subjects, to lead the English army against France.

While John's former noblemen swear allegiance to Louis, Pandolf explains John's scheme, but Louis refuses to be taken in by it. The Bastard arrives with the English army and threatens Louis, but to no avail. War breaks out with substantial losses on each side, including Louis' reinforcements, who are drowned during the sea crossing. Many English nobles return to John's side after a dying French nobleman, Melun, warns them that Louis plans to kill them after his victory.

John is poisoned by a disgruntled monk. His nobles gather around him as he dies. The Bastard plans the final assault on Louis' forces, until he is told that Pandolf has arrived with a peace treaty. The English nobles swear allegiance to John's son Prince Henry, and the Bastard reflects that this episode has taught that internal bickering could be as perilous to England's fortunes as foreign invasion.

Sources

King John is closely related to an anonymous history play, The Troublesome Reign of King John (c. 1589), the "masterly construction"[9] but infelicitous expression of which led Peter Alexander to argue that Shakespeare's was the earlier play.[lower-alpha 5] E. A. J. Honigmann elaborated these arguments, both in his preface to the second Arden edition of King John,[13] and in his 1982 monograph on Shakespeare's influence on his contemporaries.[14] The majority view, however, first advanced in a rebuttal of Honigmann's views by Kenneth Muir,[15] holds that the Troublesome Reign antedates King John by a period of several years; and that the skilful plotting of the Troublesome Reign is neither unparalleled in the period, nor proof of Shakespeare's involvement.[16]

Shakespeare derived from Holinshed's Chronicles certain verbal collocations and points of action.[lower-alpha 6] Honigmann discerned in the play the influence of John Foxe's Acts and Monuments, Matthew Paris' Historia Maior, and the Latin Wakefield Chronicle,[18] but Muir demonstrated that this apparent influence could be explained by the priority of the Troublesome Reign, which contains similar or identical matter.[lower-alpha 7]

Date and text

The date of composition is unknown, but must lie somewhere between 1587, the year of publication of the second, revised edition of Holinshed's Chronicles, upon which Shakespeare drew for this and other plays, and 1598, when King John was mentioned among Shakespeare's plays in the Palladis Tamia of Francis Meres.[20] The editors of the Oxford Shakespeare conclude from the play's incidence of rare vocabulary,[21] use of colloquialisms in verse,[22] pause patterns,[23] and infrequent rhyming that the play was composed in 1596, after Richard II but before Henry IV, Part I.[24]

King John is one of only two plays by Shakespeare that are entirely written in verse, the other being Richard II.

Performance history

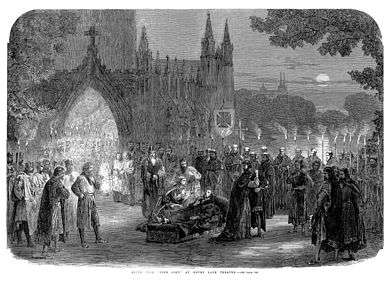

The earliest known performance took place in 1737, when John Rich staged a production at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. In 1745, the year of the Jacobite rebellion, competing productions were staged by Colley Cibber at Covent Garden and David Garrick at Drury Lane. Charles Kemble's 1823 production made a serious effort at historical accuracy, inaugurating the 19th century tradition of striving for historical accuracy in Shakespearean production. Other successful productions of the play were staged by William Charles Macready (1842) and Charles Kean (1846). Twentieth century revivals include Robert B. Mantell's 1915 production (the last production to be staged on Broadway) and Peter Brook's 1945 staging, featuring Paul Scofield as the Bastard.

In the Victorian era, King John was one of Shakespeare's most frequently staged plays, in part because its spectacle and pageantry were congenial to Victorian audiences. King John, however, has decreased in popularity: it is now one of Shakespeare's least-known plays and stagings of it are very rare.[25] It has been staged four times on Broadway, the last time in 1915.[26] It has also been staged five times from 1953 to 2014 at the Stratford Shakespeare Festival.[27]

Herbert Beerbohm Tree made a silent film version in 1899 entitled King John. It is a short film consisting of the King's death throes in Act V, Scene vii and is the earliest surviving film adaptation of a Shakespearean play. King John has been produced for television twice: in 1951 with Donald Wolfit and in 1984 with Leonard Rossiter as part of the BBC Television Shakespeare series of adaptations.[28]

George Orwell specifically praised it in 1942 for its view of politics: "When I had read it as a boy it seemed to me archaic, something dug out of a history book and not having anything to do with our own time. Well, when I saw it acted, what with its intrigues and doublecrossings, non-aggression pacts, quislings, people changing sides in the middle of a battle, and what-not, it seemed to me extraordinarily up to date."

Selected recent revivals

The Royal Shakespeare Company based in Stratford-upon-Avon presented three productions of King John: in 2006 directed by Josie Rourke as part of their Complete Works Festival[29], in 2012 directed by Maria Aberg who cast a woman, Pippa Nixon, in the role of the Bastard[30], and in 2020, directed by Eleanor Rhode and with a woman, Rosie Sheehy, cast in the role of King John. The Company's 1974–5 production was heavily rewritten by director John Barton, who included material from The Troublesome Reign of King John, John Bale's King Johan (thought to be Shakespeare's own sources) and other works.[31][32]

In 2008, the Hudson Shakespeare Company of New Jersey produced King John as part of their annual Shakespeare in the Parks series. Director Tony White set the action in the medieval era but used a multi-ethnic and gender swapping cast. The roles of Constance and Dauphin Lewis were portrayed by African American actors Tzena Nicole Egblomasse and Jessie Steward and actresses Sharon Pinches and Allison Johnson were used in several male roles. Another notable departure for the production is the depiction of King John himself. Often portrayed as an ineffectual king, actor Jimmy Pravasilis portrayed a headstrong monarch sticking to his guns on his right to rule and his unwillingness to compromise became the result of his downfall.[33]

New York's Theater for a New Audience presented a "remarkable" in-the-round production in 2000, emphasising Faulconbridge's introduction to court realpolitik to develop the audience's own awareness of the characters' motives. The director was Karin Coonrod.[34][35]

In 2012, Bard on the Beach[36] in Vancouver, British Columbia put on a production. It was also performed as part of the 2013 season at the Utah Shakespeare Festival, recipient of America's Outstanding Regional Theatre Tony Award (2000), presented by the American Theatre Wing and the League of American Theatres and Producers.

The play was presented at Shakespeare's Globe, directed by James Dacre, as part of the summer season 2015 in the 800th anniversary year of Magna Carta.[37] A co-production with Royal & Derngate, this production also played in Salisbury Cathedral, Temple Church and The Holy Sepulchre, Northampton.

The Rose Theatre, Kingston upon Thames, Surrey hosted Sir Trevor Nunn's direction of the play during May and June 2016, in the quatercentenary year of Shakespeare's death and the 800th anniversary year of King John's death.

The Worcester Repertory Company staged a production of the play (directed by Ben Humphrey) in 2016 around the tomb of King John in Worcester Cathedral on the 800th anniversary of the King's death.[38] King John was played by Phil Leach.[38]

See also

- Blank verse

- Illegitimacy in fiction

- Gild the lily

Notes

- Appears variously in the Folio of 1623 as Elinor, Eleanor, Ele., Elea., and Eli. Contemporary editors unanimously prefer the form Eleanor.[2][3][4][5]

- The First Folio uses the spelling "Britaine", which it also uses in Cymbeline when it means "Britain".

- The First Folio normally refers to him as the "Dolphin", which is a literal translation of the French title "Dauphin".

- Braunmuller,[6] following Wilson, rejects his identification with Hubert de Burgh on the basis of the exchange at 4.3.87–89. 'BIGOT: Out, dunghill! Dar'st thou brave a nobleman?' 'HUBERT: Not for my life; but yet I dare defend / My innocent life against an emperor'.[7]

- Alexander (1929),[10] cited in Honigmann (1983);[11] and Alexander (1961).[12]

- Although the author of the Troublesome Reign also drew upon Holinshed's work, the appearance in King John of material derived from Holinshed but unexampled in the other play suggests both authors independently consulted the Chronicles.[17]

- With the exception of Eleanor's dying on 1 April, which Muir argues was derived not from the Wakefield Chronicle, as Honigmann had argued, but from the conjunction of Eleanor's death and a description of an inauspicious celestial omen on 1 April on a particular page of Holinshed.[19]

Citations

- William Shakespeare. King John. Arden Shakespeare Third Series edited by Jesse M. Lander and J.J.M. Tobin, Bloomsbury, 2018, 65–102

- Braunmuller (2008), p. 117.

- Jowett (2005), p. 426.

- Beaurline (1990), p. 60.

- Honigmann (1965), p. 3.

- Braunmuller (2008), p. 277, fn 2.

- Jowett (2005), p. 446.

- William Shakespeare. King John. Arden Shakespeare Third Series edited by Jesse M. Lander and J.J.M. Tobin, Bloomsbury, 2018, 165

- Tillyard (1956), p. 216.

- Alexander (1929), pp. 201 ff.

- Honigmann (1983), p. 56.

- Alexander (1961), p. 85.

- Honigmann (1965), pp. xviii ff..

- Honigmann (1983), pp. 56–90.

- Muir (1977), pp. 78–85.

- Braunmuller (2008), p. 12.

- Honigmann (1965), p. xiii.

- Honigmann (1965), pp. xiii–xviii.

- Muir (1977), p. 82.

- Braunmuller (2008), p. 2.

- Wells (1987), p. 100.

- Wells (1987), p. 101.

- Wells (1987), p. 107.

- Wells (1987), p. 119.

- Dickson (2009), p. 173.

- League, The Broadway. "King John – Broadway Show". www.ibdb.com. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- Stratford Shakespeare Festival production history

- Holderness (2002), p. 23.

- Billington, Michael (4 August 2006). "King John Swan, Stratford-upon-Avon". The Guardian.

- Costa, Maddy (16 April 2012). "RSC's King John throws women into battle Shakespeare lived in a man's world – but the RSC is recasting his 'battle play' King John with women in the thick of the action". The Guardian.

- Cousin, Geraldine (1994). King John. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press. pp. 64 et sec. ISBN 0719027535.

- Curren-Aquino, edited by Deborah T. (1989). King John : new perspectives. Newark: University of Delaware Press. p. 191. ISBN 0874133378.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "THIS SUMMER ALL THE WORLD"S A STAGE Bard on the Boulevard Continues with 'King John'". Cranford Chronicle. 4 July 2008.

- Brantley, Ben (21 January 2000). "King John". New York Times.

- Bevington, David; Kastan, David, eds. (June 2013). "King John on stage". Shakespeare: King John and Henry VIII. New York: Random House.

- "Home". Bard on the Beach. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- Cavendish, Dominic (7 June 2015). "King John, Shakespeare's Globe, review: 'could hardly be more timely'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- "King John will be present for Shakespeare in the cathedral". Worcester News. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

References

- Alexander, Peter (1929). Shakespeare's "Henry VI" and "Richard III". Cambridge.

- Alexander, Peter (1961). Shakespeare's Life and Art. New York University Press.

- Dickson, Andrew (2009). Staines, Joe (ed.). The rough guide to Shakespeare. Rough Guides (2nd ed.). London. ISBN 978-1-85828-443-9.

- Jowett, John; Montgomery, William; Taylor, Gary; Wells, Stanley, eds. (2005) [1986]. The Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Works (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926718-9.

- Holderness, Graham; McCullough, Christopher (2002) [1986]. "Shakespeare on the Screen: A Selective Filmography". In Wells, Stanley (ed.). Shakespeare Survey. 39. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52377-X.

- Honigmann, E. A. J. (1983) [1982]. Shakespeare's Impact on his Contemporaries. Hong Kong: The Macmillan Press Ltd. ISBN 0-333-26938-1.

- Hunter, G. K. (1997). English Drama 1586–1642: the age of Shakespeare. The Oxford history of English Literature. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-812213-6.

- McMillin, Scott; MacLean, Sally-Beth (1999) [1998]. The Queen's Men and their plays. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59427-8.

- Muir, Kenneth (1977). The Sources of Shakespeare's Plays. London: Methuen & Co Ltd. ISBN 0-416-56270-1.

- Shakespeare, William (1965) [1954]. Honigmann, E. A. J. (ed.). King John. Welwyn Garden City: Methuen & Co Ltd.

- Shakespeare, William (1990). Beaurline, L. A. (ed.). King John (The New Cambridge Shakespeare). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29387-7.

- Shakespeare, William (2008) [1989]. Braunmuller, A. R. (ed.). The life and death of King John. Oxford World's Classics. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953714-3.

- Tillyard, E. M. W. (1956) [1944]. Shakespeare's History Plays. London: Chatto & Windus.

- Wells, Stanley; Taylor, Gary; Jowett, John; Montgomery, William (1987). William Shakespeare: a textual companion. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-812914-9.

External links

- King John at Project Gutenberg

- Complete Text of King John at MIT

- The life and death of King John – HTML version of this title.

.png)