Judith Quiney

Judith Quiney (baptised 2 February 1585 – 9 February 1662), née Shakespeare, was the younger daughter of William Shakespeare and Anne Hathaway and the fraternal twin of their only son Hamnet Shakespeare. She married Thomas Quiney, a vintner of Stratford-upon-Avon. The circumstances of the marriage, including Quiney's misconduct, may have prompted the rewriting of Shakespeare's will. Thomas was struck out, while Judith's inheritance was attached with provisions to safeguard it from her husband. The bulk of Shakespeare's estate was left, in an elaborate fee tail, to his elder daughter Susanna and her male heirs.

Judith Quiney | |

|---|---|

| Born | Judith Shakespeare |

| Baptised | 2 February 1585 |

| Died | 9 February 1662 (aged 77) |

| Nationality | English |

| Spouse(s) | Thomas Quiney |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent(s) | |

Judith and Thomas Quiney had three children. By the time of Judith Quiney's death, she had outlived her children by many years. She has been depicted in several works of fiction as part of an attempt to piece together unknown portions of her father's life.

Birth and early life

Judith Shakespeare was the daughter of William Shakespeare and Anne Hathaway. She was the younger sister of Susanna and the twin sister of Hamnet. Hamnet, however, died at the age of eleven.[1][2] Her baptism on 2 February 1585 was recorded as "Judeth Shakespeare" by the vicar, Richard Barton of Coventry, in the parish register for Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon.[1][2][3] The twins were named after a husband and wife, Hamnet and Judith Sadler,[1] who were friends of the parents. Hamnet Sadler was a baker in Stratford.

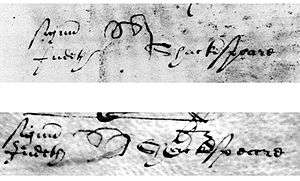

Unlike her father and her husband, Judith Shakespeare was probably illiterate. In 1611, she witnessed the deed of sale of a house for £131 (equivalent to £26,520 in 2019)[4] to William Mountford, a wheelwright of Stratford, from Elizabeth Quiney, her future mother-in-law, and Elizabeth's eldest son Adrian. Judith signed twice with a mark instead of her name.[5][6]

Marriage

On 10 February 1616, Judith Shakespeare married Thomas Quiney, a vintner of Stratford, in Holy Trinity Church. The assistant vicar, Richard Watts, who later married Quiney's sister Mary, probably officiated. The wedding took place during the pre-Lenten season of Shrovetide, which was a prohibitive time for marriages. In 1616, the period in which marriages were banned without dispensation from the church, including Ash Wednesday and Lent, started on 23 January, Septuagesima Sunday and ended on 7 April, the Sunday after Easter. Hence the marriage required a special licence issued by the Bishop of Worcester, which the couple had failed to obtain. Presumably they had posted the required banns in church, since Walter Wright of Stratford was cited for marrying without banns or licence: but this was not considered sufficient.[7] The infraction was a minor one apparently caused by the minister, as three other couples were also wed that February. Quiney was nevertheless summoned by Walter Nixon to appear before the Consistory court in Worcester. (This same Walter Nixon was later involved in a Star Chamber case and was found guilty of forging signatures and taking bribes). Quiney failed to appear by the required date. The register recorded the judgement, which was excommunication, on or about 12 March 1616. It is unknown if Judith was also excommunicated, but in any case the punishment did not last long. In November of the same year they were back in church for the baptism of their firstborn child.[8]

The marriage did not begin well. Quiney had recently impregnated another woman, Margaret Wheeler, who died in childbirth along with her child; both were buried on 15 March 1616. A few days later, on 26 March, Quiney appeared before the Bawdy Court, which dealt, among other things, with "whoredom and uncleanliness." Confessing in open court to "carnal copulation" with Margaret Wheeler, he submitted himself for correction and was sentenced to open penance "in a white sheet (according to custom)" before the Congregation on three Sundays. He also had to admit to his crime, this time wearing ordinary clothes, before the Minister of Bishopton in Warwickshire. The first part of the sentence was remitted, essentially letting him off with a five-shilling fine to be given to the parish's poor. As Bishopton had no church, but only a chapel, he was spared any public humiliation.[9]

Chapel Lane, Atwood's and The Cage

Where the Quineys lived after their marriage is unknown: but Judith owned her father's cottage on Chapel Lane, Stratford; while Thomas had held, since 1611, the lease on a tavern called "Atwood's" on High Street.[7] The cottage later passed from Judith to her sister as part of the settlement in their father's will. In July 1616 Thomas swapped houses with his brother-in-law, William Chandler, moving his vintner's shop to the upper half of a house at the corner of High Street and Bridge Street.[10] This house was known as "The Cage" and is the house traditionally associated with Judith Quiney. In the 20th century The Cage was for a time a Wimpy Bar before being turned into the Stratford Information Office.[11]

The Cage provides further insight into why Shakespeare would not have trusted Judith's husband. Around 1630 Quiney tried to sell the lease on the house but was prevented by his kinsmen. In 1633, to protect the interests of Judith and the children, the lease was signed over to the trust of John Hall, Susanna's husband, Thomas Nash, the husband of Judith's niece, and Richard Watts, vicar of nearby Harbury, who was Quiney's brother-in-law and who had officiated at Thomas and Judith's wedding. Eventually, in November 1652, the lease to The Cage ended up in the hands of Thomas' eldest brother, Richard Quiney, a grocer in London.[12]

William Shakespeare's last will and testament

The inauspicious beginnings of Judith's marriage, in spite of her husband and his family being otherwise unexceptional,[7] has led to speculation that this was the cause for William Shakespeare's hastily altered last will and testament. He first summoned his lawyer, Francis Collins, in January 1616. On 25 March he made further alterations, probably because he was dying and because of his concerns about Quiney.[13] In the first bequest of the will there had been a provision "vnto my sonne in L[aw]"; but "sonne in L[aw]" was then struck out, with Judith's name inserted in its stead.[14] To this daughter he bequeathed £100 (equivalent to £18,911 in 2019) "in discharge of her marriage porcion"; another £50 (£9,455 in 2019) if she were to relinquish the Chapel Lane cottage; and, if she or any of her children were still alive at the end of three years following the date of the will, a further £150 (£28,366 in 2019), of which she was to receive the interest but not the principal.[4] This money was explicitly denied to Thomas Quiney unless he were to bestow on Judith lands of equal value. In a separate bequest, Judith was given "my broad silver gilt bole."[14]

Finally, for the bulk of his estate, which included his main house, New Place, his two houses on Henley Street and various lands in and around Stratford, Shakespeare had set up an entail. His estate was bequeathed, in descending order of choice, to the following: 1) his daughter, Susanna Hall; 2) upon Susanna's death, "to the first sonne of her bodie lawfullie yssueing & to the heires Males of the bodie of the saied first Sonne lawfullie yssueing"; 3) to Susanna's second son and his male heirs; 4) to Susanna's third son and his male heirs; 5) to Susanna's "ffourth ... ffyfth sixte & Seaventh sonnes" and their male heirs; 6) to Elizabeth Hall, Susanna and John Hall's firstborn, and her male heirs; 7) to Judith and her male heirs; or 8) to whatever heirs the law would normally recognise. This elaborate entail is usually taken to indicate that Thomas Quiney was not to be entrusted with Shakespeare's inheritance, although some have speculated that it might simply indicate that Susanna was the favoured child.[14]

Children

Judith and Thomas Quiney had three children:

- Shakespeare (baptised 23 November 1616 – buried 8 May 1617)

- Richard (baptised 9 February 1618 – buried 6 February 1639)

- Thomas (baptised 23 January 1620 – buried 28 January 1639)

Shakespeare was named for his grandfather. Richard's name was common among the Quineys: his paternal grandfather and an uncle were named Richard.[15][16]

Shakespeare Quiney died at six months of age. Richard and Thomas Quiney were buried within one month of each other, 21 and 19 years old respectively.[15] The deaths of all of Judith's children resulted in new legal consequences. The entail on her father's inheritance led Susanna, along with her daughter and son-in-law, to make a settlement using a rather elaborate legal device for the inheritance of her own branch of the family. Legal wrangling continued for another thirteen years, until 1652.[17]

Death

Judith Quiney died by 9 February 1662, the day of her burial and a week after her 77th birthday. She outlived her last surviving child by 23 years.[6][18] She was buried in the grounds of Holy Trinity Church, but the exact location of her grave is unknown.[6] Of her husband, the records show little of his later years. It has been speculated that he may have died in 1662 or 1663, when the parish burial records are incomplete, or that he may have left Stratford-upon-Avon.[6][18] He is known to have had a nephew, living in London, who by this time was holding the lease to The Cage.

Literary references

Judith is portrayed in William Black's Judith Shakespeare: Her Love Affairs and Other Adventures, published serially in Harper's Magazine in 1884. She is one of the main characters in Edward Bond's 1973 play Bingo, which portrays the last years of her father, in retirement in Stratford on Avon. She also appears in one of the final stories in Neil Gaiman's graphic novel, The Sandman. Gaiman compared Judith with the character Miranda from Shakespeare's The Tempest.[19] She is the subject of the 2003 novel My Father Had a Daughter: Judith Shakespeare's Tale by Grace Tiffany.[20] The radio play Judith Shakespeare by Nan Woodhouse portrays her as "a loner, yearning to be a part of her playwright father's life". She travels to London to join him and has a troubling affair with a young aristocrat.[21] "Shakespeare's Daughter" is the title of a short story by Mary Burke that was short-listed for a 2007 Hennessy/Sunday Tribune Irish Writer prize.[22]

In A Room of One's Own, Virginia Woolf created a character, "Judith Shakespeare", although she is supposed to be Shakespeare's sister rather than his daughter. Besides the similar names and setting, there is no other direct connection between Judith, Shakespeare's daughter, and Woolf's creation, and in fact Shakespeare's sister was named Joan. In Woolf's story Shakespeare's sister is denied the education of her brother despite her obvious talent. When her father tries to marry her off, she runs away to join a theatre company but is ultimately rejected because of her gender. She becomes pregnant, is abandoned by her partner, and commits suicide. Woolf's Judith was created in an attempt to fill a historical gap. Woolf was making a point about the struggle that a female poet and playwright would have had in the Elizabethan age. Woolf speculated as to why there were so few talented women from that time. "What I find deplorable," she observed, "is that nothing is known about women before the eighteenth century."[23]

In Kenneth Branagh's 2018 Sony Pictures release All Is True, Kathryn Wilder plays Judith as a rebellious and angry young woman who resents her father's love for her dead twin.[24]

References

- Chambers, E. K. William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1930, 2 vols. I: 18.

- Schoenbaum, S. William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977, p. 94.

- Halliday, F. E. Shakespeare and His Critics. Gerald Duckworth & Co. London (1949). p. 28. Reprinted Nabu Press (2013) p. 28. ISBN 978-1294049265

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Schoenbaum, S. Shakespeare's Lives. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970, p. 28.

- Schoenbaum 1977, p. 318.

- Schoenbaum 1977, p. 292.

- Schoenbaum 1977, 293.

- Schoenbaum 1977, pp. 293–94.

- Schoenbaum 1977, p. 294.

- Schoenbaum 1977, p. 5.

- Schoenbaum 1977, p. 295.

- Schoenbaum 1977, p. 297.

- Chambers 1930, II: pp. 169–80.

- Chambers 1930, II: 8, 11.

- Chambers 1930, II: 104.

- Chambers 1930, II: 179–80.

- Chambers1930, p. 13.

- Gaiman, Neil, et al. The Wake. New York: DC Comics, 1997. ISBN 1-56389-279-0

- Schaal, Carol. "My Father Had a Daughter: Judith Shakespeare's Tale". Archived from the original on 1 July 2007. Retrieved 19 September 2010.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) in Notre Dame Magazine Online Archived 16 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, University of Notre Dame, 12 July 2004. Archived article accessed 9 August 2007.

- Radio 4 Extra: Judith Shakespeare Archived 2 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "'Shakespeare's Daughter' (short fiction); short-listed for 2007 Hennessy/Sunday Tribune Irish Writer prize; published in New Irish Writing (Sunday Tribune)". www.academia.edu. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- Ezell, Margaret J. M. Writing Women's Literary History. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1933, pp. 44–45 ISBN 0-8018-4432-0.

- All is True Web site, retrieved 8/18/2019.

Bibliography

- Chambers, Edmund Kerchever (1930). William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 353406.

- Chambers, Edmund Kerchever (1970). Sources for a Biography of Shakespeare. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 59179182.

- Halliwell-Phillipps, James Orchard (1882). Outlines of the life of Shakespeare. London: Longmans. OCLC 5190346.

- Schoenbaum, Samuel (1991). Shakespeare's Lives. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-818618-5.

- Schoenbaum, Samuel (1977). William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-505161-0.

.png)