Perphenazine

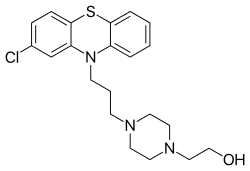

Perphenazine is a typical antipsychotic drug. Chemically, it is classified as a piperazinyl phenothiazine. Originally marketed in the US as Trilafon, it has been in clinical use for decades.

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682165 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Oral and IM |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 40% |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 8-12 (up to 20) hours |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.346 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H26ClN3OS |

| Molar mass | 403.97 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Perphenazine is roughly ten times as potent as chlorpromazine;[1] thus perphenazine is considered a medium-potency antipsychotic.[2][3]

Medical uses

In low doses it is used to treat agitated depression (together with an antidepressant). Fixed combinations of perphenazine and the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline in different proportions of weight exist (see Etrafon below). When treating depression, perphenazine is discontinued as fast as the clinical situation allows. Perphenazine has no intrinsic antidepressive activity. Several studies show that the use of perphenazine with fluoxetine (Prozac) in patients with psychotic depression is most promising, although fluoxetine interferes with the metabolism of perphenazine, causing higher plasma levels of perphenazine and a longer half-life. In this combination the strong antiemetic action of perphenazine attenuates fluoxetine-induced nausea and vomiting (emesis), as well as the initial agitation caused by fluoxetine. Both actions can be helpful for many patients.

Perphenazine has been used in low doses as a 'normal' or 'minor' tranquilizer in patients with a known history of addiction to drugs or alcohol, a practice which is now strongly discouraged.

Perphenazine has sedating and anxiolytic properties, making the drug useful for the treatment of agitated psychotic patients.

A valuable off-label indication is the short-time treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum, in which pregnant women experience violent nausea and vomiting. This problem can become severe enough to endanger the pregnancy. As perphenazine has not been shown to be teratogenic and works very well, it is sometimes given orally in the smallest possible dose.

Effectiveness

Perphenazine is used to treat psychosis (e.g. in people with schizophrenia and the manic phases of bipolar disorder). Perphenazine effectively treats the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, such as hallucinations and delusions, but its effectiveness in treating the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, such as flattened affect and poverty of speech, is unclear. Earlier studies found the typical antipsychotics to be ineffective or poorly effective in the treatment of negative symptoms,[4] but two recent, large-scale studies found no difference between perphenazine and the atypical antipsychotics.[5] A 2015 systematic review compared Perphenazine with other antipsychotic drugs:

| Summary | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Although perphenazine has been used in randomized trials for more than 50 years, incomplete reporting and the variety of comparators used make it impossible to draw clear conclusions. All data for the main outcomes were of very low quality evidence. At best it can be said that perphenazine showed similar effects - including adverse events - as several of the other antipsychotic drugs.[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Side effects

As a member of the phenothiazine type of antipsychotics, perphenazine shares in general all allergic and toxic side-effects of chlorpromazine. A 2015 systematic review of the data on perphenazine conducted by the Cochrane Collaboration concluded that "there were no convincing differences between perphenazine and other antipsychotics" in the incidence of adverse effects.[6] Perphenazine causes early and late extrapyramidal side effects more often than placebo, and at a similar rate to other medium-potency antipsychotics[7] and the atypical antipsychotic risperidone.[8][9]

When used for its strong antiemetic or antivertignosic effects in cases with associated brain injuries, it may obscure the clinical course and interferes with the diagnosis. High doses of perphenazine can cause temporary dyskinesia. As with other typical antipsychotics, permanent or lasting tardive dyskinesia is a risk.

Discontinuation

The British National Formulary recommends a gradual withdrawal when discontinuing antipsychotics to avoid acute withdrawal syndrome or rapid relapse.[10] Symptoms of withdrawal commonly include nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite.[11] Other symptoms may include restlessness, increased sweating, and trouble sleeping.[11] Less commonly there may be a feeling of the world spinning, numbness, or muscle pains.[11] Symptoms generally resolve after a short period of time.[11]

There is tentative evidence that discontinuation of antipsychotics can result in psychosis.[12] It may also result in reoccurrence of the condition that is being treated.[13] Rarely tardive dyskinesia can occur when the medication is stopped.[11]

Pharmacokinetics

It has an oral bioavailability of approximately 40% and a half-life of 8 to 12 hours (up to 20 hours), and is usually given in 2 or 3 divided doses each day. It is possible to give two-thirds of the daily dose at bedtime and one-third during breakfast to maximize hypnotic activity during the night and to minimize daytime sedation and hypotension without loss of therapeutic activity.

Pharmacodynamics

Perphenazine has the following binding profile towards cloned human receptors unless otherwise specified:[14][15]

| Molecular target | Binding affinity (Ki[nM]) for perphenazine | Binding affinity (Ki[nM]) for dealkylperphenazine | Binding affinity (Ki[nM]) for 7-hydroxyperphenazine |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 421 | - | - |

| 5-HT2A | 5.6 | 54 | 38 |

| 5-HT2C | 132 | - | - |

| 5-HT6 | 17 | - | - |

| 5-HT7 | 23 | - | - |

| α1A | 10 | - | - |

| α2A | 810 | - | - |

| α2B | 104.9 | - | - |

| α2C | 85.2 | - | - |

| M1 | 2000 | 130 | 3400 |

| M3 | 1848 | - | - |

| D1 | 29.9 (RS) | - | - |

| D2 | 0.765 | - | - |

| D2L receptor | 3.4 | 85 | 4.1 |

| D3 | 0.13 | - | - |

| D4 | 17 | - | - |

| D4.4 receptor | 140 | 690 | 620 |

| H1 | 8 | - | - |

| σ | 18.5 (RB) | - | - |

Acronyms:

RS — Rat striatum receptor.

RB — Rat brain receptor.

Formulations

It is sold under the brand names Trilafon (single drug) and Etrafon/Triavil/Triptafen[16] (contains fixed dosages of amitriptyline). A brand name in Europe is Decentan pointing to the fact that perphenazine is approximately 10-times more potent than chlorpromazine. Usual oral forms are tablets (2, 4, 8, 16 mg) and liquid concentrate (4 mg/ml).

The 'Perphenazine injectable USP' solution is intended for deep intramuscular (i.m.) injection, for patients who are not willing to take oral medication or if the patient is unable to swallow. Due to a better bioavailability of the injection, two-thirds of the original oral dose is sufficient. The incidence of hypotension, sedation and extrapyramidal side-effects may be higher compared to oral treatment. The i.m.-injections are appropriate for a few days, but oral treatment should start as soon as possible.

In many countries, depot forms of perphenazine exist (as perphenazine enanthate). One injection works for 1 to 4 weeks depending on the dose of the depot-injection. Depot-forms of perphenazine should not be used during the initial phase of treatment as the rare neuroleptic malignant syndrome may become more severe and uncontrollable with this form. Extrapyramidal side-effects may be somewhat reduced due to constant plasma-levels during depot-therapy. Also, patient compliance is sure, as many patients do not take their oral medication, particularly if feeling better once improvement in psychosis is achieved.

Interactions

Fluoxetine causes higher plasma-levels and a longer half-life of perphenazine, therefore a dose reduction of perphenazine might be necessary.

Perphenazine intensifies the central depressive action of drugs with such activity (tranquilizers, hypnotics, narcotics, antihistaminics, OTC-antiemetics etc.). A dose reduction of perphenazine or the other drug may be necessary.

In general, all neuroleptics may lead to seizures in combination with the opioid tramadol (Ultram).

Perphenazine may increase the insulin needs of diabetic patients. Monitor blood glucose levels of insulin-dependent patients regularly during long-term treatment.

References

- Rees L (August 1960). "Chlorpromazine and allied phenothiazine derivatives". British Medical Journal. 2 (5197): 522–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5197.522. PMC 2097091. PMID 14436902.

- Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Faries D, Landbloom R, Swartz M, Swanson J (2006). "Time to discontinuation of atypical versus typical antipsychotics in the naturalistic treatment of schizophrenia". BMC Psychiatry. 6: 8. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-6-8. PMC 1402287. PMID 16504026.

- Freudenreich, Oliver (2007). "Treatment of psychotic disorders". Psychotic disorders. Practical Guides in Psychiatry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-7817-8543-3. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- King DJ (February 1998). "Drug treatment of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 8 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1016/S0924-977X(97)00041-2. PMID 9452938.

- Lieberman JA (October 2006). "Comparative effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs. A commentary on: Cost Utility Of The Latest Antipsychotic Drugs In Schizophrenia Study (CUtLASS 1) and Clinical Antipsychotic Trials Of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE)". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (10): 1069–72. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1069. PMID 17015808.

- Hartung, B; Sampson, S; Leucht, S (2015). "Perphenazine for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD003443.pub3. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003443.pub3. PMID 25749632.

- Kelsey, Jeffrey E; Newport, D Jeffrey; Nemeroff, Charles B (2006). "Schizophrenia". Principles of psychopharmacology for mental health professionals (illustrated ed.). John Wiley and Sons. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-471-25401-0. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- Schillevoort I, de Boer A, Herings RM, Roos RA, Jansen PA, Leufkens HG (July 2001). "Antipsychotic-induced extrapyramidal syndromes. Risperidone compared with low- and high-potency conventional antipsychotic drugs". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 57 (4): 327–31. doi:10.1007/s002280100302. PMID 11549212.

- Høyberg OJ, Fensbo C, Remvig J, Lingjaerde O, Sloth-Nielsen M, Salvesen I (December 1993). "Risperidone versus perphenazine in the treatment of chronic schizophrenic patients with acute exacerbations". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 88 (6): 395–402. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(98)80046-5. PMID 7508675.

- Joint Formulary Committee, BMJ, ed. (March 2009). "4.2.1". British National Formulary (57 ed.). United Kingdom: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-85369-845-6.

Withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs after long-term therapy should always be gradual and closely monitored to avoid the risk of acute withdrawal syndromes or rapid relapse.

- Haddad, Peter; Haddad, Peter M.; Dursun, Serdar; Deakin, Bill (2004). Adverse Syndromes and Psychiatric Drugs: A Clinical Guide. OUP Oxford. p. 207-216. ISBN 9780198527480.

- Moncrieff J (July 2006). "Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 114 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00787.x. PMID 16774655.

- Sacchetti, Emilio; Vita, Antonio; Siracusano, Alberto; Fleischhacker, Wolfgang (2013). Adherence to Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 85. ISBN 9788847026797.

- National Institute of Mental Health. PDSD Ki Database (Internet) [cited 2013 Oct 3]. Chapel Hill (NC): University of North Carolina. 1998-2013. Available from: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-11-08. Retrieved 2013-11-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Sweet, RA; Pollock, BG; Mulsant, BH; Rosen, J; Sorisio, D; Kirshner, M; Henteleff, R; DeMichele, MA (April 2000). "Pharmacologic Profile of Perphenazine's Metabolites". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 20 (2): 181–187. doi:10.1097/00004714-200004000-00010. PMID 10770456.

- "Triptafen | Mind, the mental health charity - help for mental health problems". www.mind.org.uk. Retrieved 2017-03-19.