Maastricht Treaty

The Maastricht Treaty (officially the Treaty on European Union) was a treaty signed on 7 February 1992 by the members of the European Communities in Maastricht, Netherlands, to further European integration.[1] On 9–10 December 1991, the same city hosted the European Council which drafted the treaty.[2] The treaty founded the European Union and established its pillar structure which stayed in place until the Lisbon Treaty came into force in 2009. The treaty also greatly expanded the competences of the EEC/EU and led to the creation of the single European currency, the euro.

| Type | Founding treaty |

|---|---|

| Signed | 7 February 1992 |

| Location | Maastricht, Netherlands |

| Effective | 1 November 1993 |

| Amendment | Treaty of Amsterdam (1999) Treaty of Nice (2003) Treaty of Lisbon (2009) |

| Signatories | EU member states |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the European Union |

|

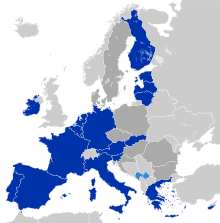

Member States (27) Candidate countries for EU Accession

European Union since 31 January 2020 |

Treaties of Accession

Treaties of Succession

Other Treaties

Abandoned treaties and agreements

|

|

Executive

|

|

Legislature

European Parliament

(Members)

National parliaments |

|

Judiciary Court of Justice of the EU

|

|

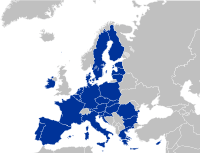

Schengen Area Member States

Schengen Area since 2015 |

|

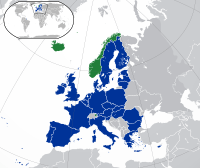

EEA Members

European Economic Area |

|

|

Other Bodies |

Elections in EU Member States

|

|

|

Policies and Issues

|

|

Other Other currencies in use

Non-Schengen Area States

|

|

Foreign Relations High Representative

Foreign relations of EU Member States

|

|

The Maastricht Treaty reformed and amended the treaties establishing the European Communities, the EU's first pillar. It renamed European Economic Community to European Community to reflect its expanded competences beyond economic matters. The Maastricht Treaty also created two new pillars of the EU on Common Foreign and Security Policy and Cooperation in the Fields of Justice and Home Affairs (respectively the second and third pillars), which replaced the former informal intergovernmental cooperation bodies named TREVI and European Political Cooperation on EU Foreign policy coordination.

The Maastricht Treaty (TEU) and all pre-existing treaties has subsequently been further amended by the treaties of Amsterdam (1997), Nice (2001) and Lisbon (2007). Today it is one of two treaties forming the constitutional basis of the European Union (EU), the other being the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

History

While the current version of the TEU entered into force in 2009, following the Treaty of Lisbon (2007), the older form of the same document was implemented by the Treaty of Maastricht (1992).

Signing

The signing of the Treaty of Maastricht took place in Maastricht, Netherlands, on 7 February 1992. The Dutch government, by virtue of holding Presidency of the Council of the European Union during the negotiations in the second half of 1991, arranged a ceremony inside the government buildings of the Limburg province on the river Maas (Meuse). Representatives from the twelve member states of the European Communities were present, and signed the treaty as plenipotentiaries, marking the conclusion of the period of negotiations.

Ratification

Only three countries held referendums (France, Denmark and Ireland – all required by their respective constitutions).[3] The process of ratifying the treaty was fraught with difficulties in three states. In Denmark, the first Danish Maastricht Treaty referendum was held on 2 June 1992 and ratification of the treaty was rejected by a margin of 50.7% to 49.3%.[4] Subsequently, alterations were made to the treaty through the addition of the Edinburgh Agreement which lists four Danish exceptions, and this treaty was ratified the following year on 18 May 1993 after a second referendum was held in Denmark,[5] with legal effect after the formally granted royal assent on 9 June 1993.[6]

In September 1992, a referendum in France only narrowly supported the ratification of the treaty, with 50.8% in favour. This narrow vote for ratification in France, known at the time as the 'petite oui', led Jacques Delors to comment that "Europe began as an elitist project in which it was believed that all that was required was to convince the decision-makers. That phase of benign despotism is over."[7]

In the United Kingdom, an opt-out from the treaty's social provisions was opposed in Parliament by the opposition Labour and Liberal Democrat MPs and the treaty itself by the Maastricht Rebels within the governing Conservative Party. The number of rebels exceeded the Conservative majority in the House of Commons, and thus the government of John Major came close to losing the confidence of the House.[8] In accordance with British constitutional convention, specifically that of parliamentary sovereignty, ratification in the UK was not subject to approval by referendum. Despite this, the British constitutional historian Vernon Bogdanor suggests that there was "a clear constitutional rationale for requiring a referendum" based on the allocation of legislative power.[9][10]

At the end of January 2020 (GMT), the UK left the EU and so withdrew from this Treaty.

Entry into force

The TEU entered into force on 1 November 1993.

Amendments

Treaties amending the TEU:

- Treaty of Amsterdam (1999)

- Treaty of Nice (2003)

- Treaty of Lisbon (2009)

Historical assessment

The treaty led to the creation of the euro. One of the obligations of the treaty for the members was to keep "sound fiscal policies, with debt limited to 60% of GDP and annual deficits no greater than 3% of GDP".[11] This obligation has not been met, with debt to GDP levels increasing steadily in most countries in eurozone since the treaty was signed with the average for the zone standing at 85%, and much higher for some countries, e.g. France, where debt to GDP ratios reached 98% in 2019, or Greece at 181%.[12]

The treaty also created what was commonly referred to as the pillar structure of the European Union.

The treaty established the three pillars of the European Union—one supranational pillar created from three European Communities (which included the European Economic Community (EEC), the European Coal and Steel Community and the European Atomic Energy Community), the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) pillar, and the Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) pillar. The first pillar was where the EU's supra-national institutions—the Commission, the European Parliament and the European Court of Justice—had the most power and influence. The other two pillars were essentially more intergovernmental in nature with decisions being made by committees composed of member states' politicians and officials.[13]

All three pillars were the extensions of existing policy structures. The European Community pillar was the continuation of the European Economic Community with the "Economic" being dropped from the name to represent the wider policy base given by the Maastricht Treaty. Coordination in foreign policy had taken place since the beginning of the 1970s under the name of European Political Cooperation (EPC), which had been first written into the treaties by the Single European Act but not as a part of the EEC. While the Justice and Home Affairs pillar extended cooperation in law enforcement, criminal justice, asylum, and immigration and judicial cooperation in civil matters, some of these areas had already been subject to intergovernmental cooperation under the Schengen Implementation Convention of 1990.

The creation of the pillar system was the result of the desire by many member states to extend the European Economic Community to the areas of foreign policy, military, criminal justice, and judicial cooperation. This desire was set off against the misgivings of other member states, notably the United Kingdom, over adding areas which they considered to be too sensitive to be managed by the supra-national mechanisms of the European Economic Community. The agreed compromise was that instead of renaming the European Economic Community as the European Union, the treaty would establish a legally separate European Union comprising the renamed European Economic Community, and the inter-governmental policy areas of foreign policy, military, criminal justice, judicial cooperation. The structure greatly limited the powers of the European Commission, the European Parliament and the European Court of Justice to influence the new intergovernmental policy areas, which were to be contained with the second and third pillars: foreign policy and military matters (the CFSP pillar) and criminal justice and cooperation in civil matters (the JHA pillar).

In addition, the treaty established the European Committee of the Regions (CoR). CoR is the European Union's (EU) assembly of local and regional representatives that provides sub-national authorities (i.e. regions, municipalities, cities, etc.) with a direct voice within the EU's institutional framework.

The Maastricht criteria

The Maastricht criteria (also known as the convergence criteria) are the criteria for European Union member states to enter the third stage of European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and adopt the euro as their currency. The four criteria are defined in article 121 of the treaty establishing the European Community. They impose control over inflation, public debt and the public deficit, exchange rate stability and the convergence of interest rates.

1. Inflation rates: No more than 1.5 percentage points higher than the average of the three best performing (lowest inflation) member states of the EU.

2. Government finance:

- Annual government deficit:

- The ratio of the annual government deficit to gross domestic product (GDP) must not exceed 3% at the end of the preceding fiscal year. If not, it is at least required to reach a level close to 3%. Only exceptional and temporary excesses would be granted for exceptional cases.

- Government debt:

- The ratio of gross government debt to GDP must not exceed 60% at the end of the preceding fiscal year. Even if the target cannot be achieved due to the specific conditions, the ratio must have sufficiently diminished and must be approaching the reference value at a satisfactory pace. As of the end of 2014, of the countries in the Eurozone, only Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Luxembourg, and Finland still met this target.[14]

3. Exchange rate: Applicant countries should have joined the exchange-rate mechanism (ERM II) under the European Monetary System (EMS) for two consecutive years and should not have devalued its currency during the period.

4. Long-term interest rates: The nominal long-term interest rate must not be more than 2 percentage points higher than in the three lowest inflation member states.

The purpose of setting the criteria is to maintain price stability within the Eurozone even with the inclusion of new member states.[11]

See also

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Treaties of the European Union

- Treaty on European Union

- Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

Notes

- "1990–1999". The history of the European Union – 1990–1999. Europa. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- "1991". The EU at a glance – The History of the European Union. Europa. Archived from the original on 5 April 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- Parsons, Craig (2006). A Certain Idea of Europe. Cornell University Press. p.202. ISBN 9780801440861

- Havemann, Joel (4 June 1992). "EC Leaders at Sea Over Danish Rejection: Europe: Vote against Maastricht Treaty blocks the march to unity. Expansion plans may also be in jeopardy". LA Times. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- "In Depth: Maastricht Treaty". BBC News. 30 April 2001. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- "Lov om Danmarks tiltrædelse af Edinburgh-Afgørelsen og Maastricht-Traktaten (*1)" (in Danish). Retsinformation. 9 June 1993.

- Anell, Lars (2014). Democracy in Europe – An essay on the real democratic problem in the European Union. p.23. Forum för EU-Debatt.

- Goodwin, Stephen (23 July 1993). "The Maastricht Debate: Major 'driven to confidence factor': Commons Exchanges: Treaty issue 'cannot fester any longer'". The Independent. London. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- Bogdanor quotes John Locke's The Second Treatise of Government: "The Legislative cannot transfer the power of making laws to any other hands. For it being but a delegated power from the People, they who have it cannot pass it to others." Bogdanor, Vernon (8 June 1993). "Why the people should have a vote on Maastricht: The House of Lords must uphold democracy and insist on a referendum". The Independent.

- Bogdanor, Vernon (26 July 1993). "Futility of a House with no windows". The Independent.

- . Hubbard, Glenn and Tim Kane. (2013). Balance: The Economics of Great Powers From Ancient Rome to Modern America . Simon & Schuster. P. 204. ISBN 978-1-4767-0025-0

- "General government gross debt - annual data (table code: teina225)". Eurostat. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- "Treaties and law". European Union. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- "Eurostat – Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table". ec.europa.eu.

Further reading

- Christiansen, Thomas; Duke, Simon; Kirchner, Emil (November 2012). "Understanding and assessing the Maastricht Treaty". Journal of European Integration. 34 (7): 685–698. doi:10.1080/07036337.2012.726009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Michael (November 2012). "Still rooted in Maastricht: EU external relations as a 'third-generation hybrid'". Journal of European Integration. 34 (7): 699–715. doi:10.1080/07036337.2012.726010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Monar, Jörg (November 2012). "Justice and Home Affairs: the treaty of Maastricht as a decisive intergovernmental gate opener". Journal of European Integration. 34 (7): 717–734. doi:10.1080/07036337.2012.726011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Monar, Jörg (November 2012). "Twenty years of co-decision since Maastricht: inter- and intrainstitutional implications". Journal of European Integration. 34 (7): 735–751. doi:10.1080/07036337.2012.726012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wessels, Wolfgang (November 2012). "The Maastricht Treaty and the European Council: the history of an institutional evolution". Journal of European Integration. 34 (7): 753–767. doi:10.1080/07036337.2012.726013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Caporaso, James A.; Kim, Min-hyung (November 2012). "The Maastricht Treaty at twenty: a Greco-European tragedy?". Journal of European Integration. 34 (7): 769–789. doi:10.1080/07036337.2012.726014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dyson, Kenneth (November 2012). "'Maastricht plus': managing the logic of inherent imperfections". Journal of European Integration. 34 (7): 791–808. doi:10.1080/07036337.2012.726015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kohler-Koch, Beate (November 2012). "Post-Maastricht civil society and participatory democracy". Journal of European Integration. 34 (7): 809–824. doi:10.1080/07036337.2012.726016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weiler, J.H.H. (November 2012). "In the face of crisis: input legitimacy, output legitimacy and the political Messianism of European integration". Journal of European Integration. 34 (7): 825–841. doi:10.1080/07036337.2012.726017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dinan, Desmond (November 2012). "The arc of institutional reform in post-Maastricht Treaty change". Journal of European Integration. 34 (7): 843–858. doi:10.1080/07036337.2012.726018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()

- Full text of the treaty at EUR-Lex

- The Treaty on European Union, signed at Maastricht on 7 February 1992 – Original version

- The History of the European Union – The Treaty of Maastricht

- Maastricht Treaty (7 February 1992) CVCE

- Proposed 1962 treaty establishing a "European Union" CVCE

- The Treaty on European Union – Current consolidated versions of the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (in PDF)