European Investment Bank

The European Investment Bank (EIB) is a publicly owned international financial institution whose shareholders are the EU member states. It was established in 1958 under the Treaty of Rome as a "policy-driven bank" using financing operations to further EU policy goals [1] such as European integration and social cohesion.[2] It should not be confused with the European Central Bank, which is based in Frankfurt (Germany) or with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) which is based in London (United Kingdom).

.svg.png) | |

EIB headquarters, East building | |

| Founded | 1958 |

|---|---|

| Type | International financial institution |

| Location |

|

| Owner | EU member states |

President | Werner Hoyer |

Employees | 3410 |

| Website | www |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the European Union |

|

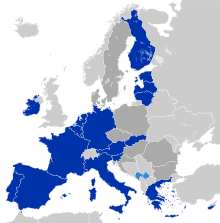

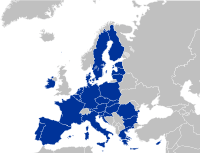

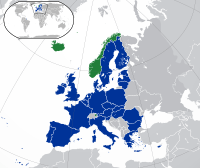

Member States (27) Candidate countries for EU Accession

European Union since 31 January 2020 |

Treaties of Accession

Treaties of Succession

Other Treaties

Abandoned treaties and agreements

|

|

Executive

|

|

Legislature

European Parliament

(Members)

National parliaments |

|

Judiciary Court of Justice of the EU

|

|

Schengen Area Member States

Schengen Area since 2015 |

|

EEA Members

European Economic Area |

|

|

Other Bodies |

Elections in EU Member States

|

|

|

Policies and Issues

|

|

Other Other currencies in use

Non-Schengen Area States

|

|

Foreign Relations High Representative

Foreign relations of EU Member States

|

|

The member states set the bank's broad policy goals and oversee the decision-making bodies of the bank: its board of governors and board of directors.[3] It is the world's largest international public lending institution.[4]

History

The European Investment Bank was founded when the Treaty of Rome came into force 1958, located in Brussels and with 66 employees.[5] In 1968 it was relocated to Luxembourg, where it remains. By 1999, it had more than 1,000 staff members, and more than 2,000 in 2012.

The EIB Group was formed in 2000, comprising the EIB and the European Investment Fund (EIF), the EU's venture capital arm that provides finances and guarantees for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The EIB is the EIF's majority shareholder, with 62% of the shares.[6] In 2012, the EIB Institute was created, with the goal of promoting "European initiatives for the common good" in EU Member States and candidate and potential candidate countries, as well as EFTA nations.

The total subscribed capital of the Bank was EUR 232 billion in 2012.[7] The capital of the EIB was virtually doubled between 2007 and 2009 in response to the financial crisis. The EU heads of government agreed to increase paid-in capital by EUR 10 billion in June 2012, with implementation expected in early 2013.

For the fiscal year 2011, EIB lent EUR 61 billion in various loan products, bringing total outstanding loans to EUR 395 billion; one-third higher than at the end of 2008. Nearly 90% of these were with EU member states with the remainder dispersed between around 150 "partner countries" (in southern and eastern Europe, the Mediterranean region, Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean and the Pacific). The bank uses its AAA credit rating to fund itself by raising equivalent amounts on the capital markets.

Mission

As the "Bank of the European Union", the EIB's mission is to make a difference to the future of Europe and its partners by supporting sound investments which further EU policy goals.[1]

Although about 90 percent of projects financed by the EIB are based in EU member countries, the bank does fund projects in about 150 other countries—non-EU Southeastern European countries, Mediterranean partner countries, ACP countries, Asian and Latin American countries, the members of the Eastern Partnership and Russia.[8] According to the EIB, it works in these countries to implement the financial pillar of the union's external cooperation and development policies by encouraging private sector development, infrastructure development, security of energy supply and environmental sustainability. EU finance ministers have "called on all multilateral development banks, such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, to phase out financing of fossil fuel projects."[9]

In the wake of the 2014 Russian military intervention in Ukraine, the Council of the European Union instructed the EIB to suspend new financing operations in Russia.[10]

Strategy

Operating strategy:

- To finance viable capital projects which further EU objectives

- To borrow on the capital markets to finance these projects

Lending strategy within the EU

Within the EU the EIB has six priority objectives:

- Cohesion and convergence (regional policy)

- Support for small and medium-sized enterprises

- Environmental sustainability

- Knowledge economy

- Development of Trans-European Networks of transport and energy

- Sustainable, competitive, and secure energy supply

Lending strategy outside the EU

Outside the EU the EIB's priority objectives for lending activity are:

- Private sector development

- Financial sector development

- Infrastructure development

- Security of energy supply

- Environmental sustainability

- EU presence

When making loans outside the EU, the bank has lending mandates based on EU external cooperation and development policies, which differ from region to region.

- Pre-Accession: Candidate and Potential Candidate countries in the Enlargement region (states which could possibly join the EU)

- European Neighbourhood: Mediterranean Neighbourhood / Russia and Eastern Neighbours

- Development: Africa, Pacific and Caribbean (ACP) / Republic of South Africa

- Economic Cooperation: Asia and Latin America (ALA)

Within pre-accession countries, activities support both the EU priority lending objectives and the objectives of the external mandates.[1]

Corporate policies

Transport Policy (renewed in 2011), Energy Policy (2012), Transparency Policy (latest renewal in 2015), Climate Strategy (2015), Governance at the EIB, Complaints Mechanism Policy (renewed in 2010), Anti-Fraud and Anti-Corruption Policy, Integrity Policy and Compliance Charter, Statement on Environmental and Social Principles and Standards, EIB Whistleblowing Policy, EIB Policy towards weakly regulated, non-transparent and uncooperative jurisdictions. As such, the European Investment Bank is currently represented in the Standard Committee of SuRe® – The Standard for Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure, which is a global voluntary standard, developed by the Swiss Global Infrastructure Basel Foundation and the French bank Natixis, which integrates key criteria of sustainability and resilience into infrastructure development and upgrade.[11]

Climate

On 14 November 2019, the EIB announced that it would stop funding new, unabated, fossil fuel projects from the end of 2021, including an end to funding for natural gas.[12][13][14] Current projects, such as the Trans Adriatic Pipeline, will not be affected.[15]

The bank announced an intention to "support €1 trillion of climate related investment" in "the coming years."[15] Examples of planned expenditures include the Just Transition Fund which "will finance up to 75% of projects such as reconversion of coal mines" in coal dependent regions.[15]

Governance

The EIB is governed by the:

- Board of Governors – usually the Finance Ministers of the Member States. Their mandate is to authorise EIB activities outside the Union, form credit policy guidelines and approve the annual accounts.

- Board of directors – twenty-eight members (one nominated by each member state and one by the European Commission).[16]:13–14 There are eighteen alternates,[16]:13–14 meaning that some of these positions are shared by groups of states.[17] The board also co-opts a maximum of six experts (three directors and three alternates),[16]:13–14 who participate in the Board meetings in an advisory capacity, without voting rights. The Board has sole power to take decisions in respect of loans, guarantees and borrowings. They are responsible only to the bank.

- Management committee – EIB President and eight vice-presidents

- Audit committee – six members appointed by the Board of Governors

The EIB addresses complaints internally and the bank can also be referred to the European Ombudsman if concerns about maladministration persist.[18]

Offices

The headquarters is situated at 100 Boulevard Konrad Adenauer in Kirchberg, Luxembourg.[19] The building's first phase, now the West building, was designed by British architect Sir Denys Lasdun and is one of his few works outside the UK. An extension, the East building, was designed by Ingenhoven Architects, Düsseldorf. Covered by a glass roof that spans the entire structure, the extension adds 72,500 meters of office space.[20]

The EIB has offices in the different EU countries, including Athens, Berlin, Brussels, Bucharest, Fort-de-France, Martinique (one of France's overseas departments); Dublin, Helsinki, Lisbon, Lubliana, Madrid, Paris, Rome, Sofia, Warsaw, Copenhagen and Vienna.

Outside of the EU, it has offices in Belgrade, Serbia; Bogotá, Colombia; Kiev, Ukraine; Ankara, Turkey; Beijing, China; Cairo, Egypt; Dakar, Senegal; Istanbul, Turkey; Nairobi, Kenya; Pretoria, South Africa; Rabat, Morocco; Sydney, Australia; and Tunis, Tunisia and Tbilisi, Georgia.[21]

In 2007, the EIB opened a regional office in Helsinki, located at the headquarters of the Nordic Investment Bank (NIB), with the aim of enhancing the Bank's presence in the Baltic Sea region.[22]

Presidents

The EIB president is the head of the Management Committee, a nine-member executive body that is responsible for the day-to-day operations of the EIB. They are "appointed by the EIB's Board of Governors, on a proposal from the board of directors", for a renewable six-year term. The President is also the chair of the board of directors.[23] The other eight members are vice-presidents.[24]

- Werner Hoyer (Germany): January 2012 – present[25]

- Philippe Maystadt (Belgium): March 2000 – December 2011

- Sir Brian Unwin (UK): April 1993 – December 1999

- Ernst-Günther Bröder (Germany): August 1984 – March 1993

- Yves Le Portz (France): September 1970 – July 1984

- Paride Formentini (Italy): June 1959 – September 1970

- Pietro Campilli (Italy): February 1958 – May 1959

Shareholders

The shareholders of the EIB are the 27 member states of the EU, while each state's share in the EIB's capital is based on its economic weight within the European Union (expressed in GDP) at the time of its accession.[26] Shares of capital are following:[27]

| Country | Capital (€ million) | Capital (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Germany | 46,722 | 19.21 |

| France | 46,722 | 19.21 |

| Italy | 46,722 | 19.21 |

| Spain | 28,033 | 11.52 |

| Belgium | 12,951 | 5.32 |

| Netherlands | 12,951 | 5.32 |

| Sweden | 8,591 | 3.53 |

| Denmark | 6,557 | 2.70 |

| Austria | 6,428 | 2.64 |

| Poland | 5,980 | 2.46 |

| Finland | 3,693 | 1.52 |

| Greece | 3,512 | 1.44 |

| Portugal | 2,263 | 0.93 |

| Czechia | 2,206 | 0.91 |

| Hungary | 2,087 | 0.86 |

| Ireland | 1,639 | 0.67 |

| Romania | 1,513 | 0.62 |

| Croatia | 1,062 | 0.44 |

| Slovakia | 751 | 0.31 |

| Slovenia | 697 | 0.29 |

| Bulgaria | 510 | 0.21 |

| Lithuania | 437 | 0.18 |

| Luxembourg | 327 | 0.13 |

| Cyprus | 321 | 0.13 |

| Latvia | 267 | 0.11 |

| Estonia | 206 | 0.08 |

| Malta | 122 | 0.05 |

| Total | 243.2 | 100 |

Active projects

- Crossrail, United Kingdom

- Kanpur Metro, India

- Manchester Metrolink Phase 3, United Kingdom

- Eurasia Tunnel, Turkey

- Marmaray Railway, Turkey

Controversial projects

There are a few projects financed or under the appraisal procedure by the EIB that have raised objections from local communities as well as international and national NGOs.[28][29] Such projects include the M10 motorway in Russia[30], the Gazela Bridge in Serbia,[31] Rača Bridge between Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, the D1 motorway in the Slovakia, Šoštanj Power Plant in Slovenia,[32] the Bujagali Hydroelectric Power Station in Uganda.[33]

The Transparency Policy of the EIB has been criticised by NGOs. In 2004, Article 19 issued a memorandum in which it accused the EIB of failing to meet international (including EU) standards on openness.[34] In 2010 the EIB updated its transparency policy following a public consultation.[35] The latest update of the Transparency Policy in 2015 equally followed a public consultation.

A 2011 report accused the EIB of a lending policy that failed its responsibility to further the EU goal of cutting carbon emissions.[36]

In 2014 11 NGOs demanded the release of an EIB report into allegations of tax fraud by Glencore in Zambia.[37] Following a recommendation of the European Ombudsman the EIB released a summary which stated their investigation had been "non-conclusive".[38][39] The Ombudsman subsequently called this summary inadequate and accused the EIB of failing to meet its own transparency policy.[40][41]

Reports in 2010 and 2015, from a coalition of NGOs, implicated the EIB in tax avoidance by lending to businesses which use tax havens.[42][43][44]

In 2018, seven EU governments demanded improvements in the governance and structure of the institution as well as stricter cost controls. There were concerns that EIB had been slow to implement recommendations raised by its own audit committee, which aimed at improving the risk management and project selection.[45]

See also

- Development finance institution

- Economics

- European Investment Fund

- Fossil fuel divestment

- Green New Deal

- Institutions of the European Union

- Capital Markets Union

- Banking Union

Notes and references

- "EIB Operational Plan 2012–2014". eib.org. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013.

- European Investment Bank. "What Is the EIB?". FAQ – Structure and Organisation.

- "FAQ – Structure and Organisation". Eib.org. 17 October 2011. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- van Putten, Maartje (2008). Policing the Banks: Accountability Mechanisms for the Financial Sector. Montréal [Québec]: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 146. ISBN 9780773576650. OCLC 760073184.

- "Some Dates and Figures". European Investment Bank.

- "Who are the owners of the EIB Group?". FAQ – Structure and Organisation. European Investment Bank.

- "EIB Group: key statutory figures". Eib.org. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "In which countries is the EIB active?". FAQ – Activities. European Investment Bank.

- Farand, Chloé (15 November 2019). "European Investment Bank ends lending to fossil fuel projects". Climate Home News. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- "European Council conclusions on external relations (Ukraine and Gaza)" (PDF). consilium.europa.eu/. Council of the European Union. 16 July 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- "SuRe® Standard Committee - Global Infrastructure Basel". www.gib-foundation.org.

- Ekblom, Jonas. "UPDATE 2-European Investment Bank to cease funding fossil fuel projects by end-2021". news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- Fawthrop, Andrew (15 November 2019). "EIB to end financing for fossil fuel projects by 2021". NS Energy. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- Krukowska, Ewa (14 November 2019). "EU Bank Takes 'Quantum Leap' to End Fossil-Fuel Financing". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- Barbiroglio, Emanuela. "European Investment Bank Will Stop Financing New Fossil Fuels Projects". Forbes. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- Statute of the European Investment Bank (and other provisions) (PDF). EIB. 1 December 2009. ISBN 978-92-861-1003-0. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- The alternates are nominated as follows:

- 2 by Germany

- 2 by France

- 2 by Italy

- 2 by the UK

- 1 jointly by Spain and Portugal

- 1 jointly by Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands

- 2 jointly by Denmark, Greece, Ireland and Romania

- "The EIB Complaints Mechanism". European Investment Bank. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

- Ex-post evaluation (17 October 2011). "Building". Eib.org. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "European Investment Bank (EIB)". Architonic. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- Ex-post evaluation (17 October 2011). "EIB Group addresses". Eib.org. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "EUROPA – PRESS RELEASES – Press Release – Eur 100 million EIB loan support to kemira research in Finland". Europa.eu. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "The Management Committee". About > Structure > Governance. European Investment Bank. 9 January 2012.

- "Anciens Présidents". eib.org. 4 December 2014.

- "Werner Hoyer takes office as EIB President". EIB Press Release. 21 December 2011. Archived from the original on 29 December 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- "Shareholders". eib.org. 8 February 2020.

- "EIB Statute and other Treaty provisions" (PDF). eib.org.

- Challenging the European Investment Bank (PDF)

- Michael Haines. "ClientEarth - environmental lawyers - Transparency and the European Investment Bank [318]". ClientEarth. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015.

- "Moscow - St Petersburg M11 Motorway - Verdict Traffic".

- "Eviction of Roma Sparks Controversy in Serbia".

- "EU and EIB Funding in Central and Eastern Europe: Cohesion or Collision?" (PDF). e-polis.info.

- "Going After Uganda's Big, Bad Dam Investors". International Rivers. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "NGOs Criticize EIB on Transparency, Other Grounds". Freedom Info. 7 June 2004. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- Ex-post evaluation. "EIB Transparency Policy". European Investment Bank. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

- Carrington, Damian. "European Investment Bank criticised for 'hypocrisy' of fossil fuel lending ", The Guardian, London, 8 December 2011. Retrieved on 21 July 2016.

- Jones, Sam. "European Investment Bank accused of suppressing Zambian mining report", The Guardian, London, 3 April 2014. Retrieved on 21 July 2016.

- "Update on the status of the EIB loan for the Mopani Copper Project, Zambia", European Investment Bank, 25 July 2014. Retrieved on 21 July 2016.

- "Mopani Copper Project Summary of the investigation of the Inspectorate General Fraud Investigation", European Investment Bank, 29 January 2005. Retrieved on 21 July 2016.

- "New ruling highlights ongoing secrecy around Glencore tax case in Zambia" Archived 8 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Christian Aid, London, 18 March 2015. Retrieved on 21 July 2016.

- "Decision of the European Ombudsman closing the inquiry into complaint 349/2014/OV against the European Investment Bank (EIB)", European Ombudsman, 17 March 2015. Retrieved on 21 July 2016.

- Hyslop, Leah. "EU money earmarked for African development winds up in tax havens and African banks, report claims", The Daily Telegraph, London, 1 December 2010. Retrieved on 21 July 2016.

- Hencke, David. "EU aid for Africa ends up in tax havens, watchdog claims", The Guardian, London, 25 November 2010. Retrieved on 21 July 2016.

- "Towards a responsible taxation policy for the EIB", Counter Balance, 03 April 2015. Retrieved on 21 July 2016.

- Financial Times. "European Investment Bank faces call for overhaul after UK exits". www.ft.com.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Official website

- Historical Archives of the European Investment Bank at the Historical Archives of the EU in Florence

- European Investment Bank European Navigator

- CEE Bankwatch Network's Information pages about European Investment Bank