European Coal and Steel Community

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was an organisation of six European countries created after World War II to regulate their industrial production under a centralised authority. It was formally established in 1951 by the Treaty of Paris, signed by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany. The ECSC was the first international organisation to be based on the principles of supranationalism,[2] and started the process of formal integration which ultimately led to the European Union.

European Coal and Steel Community

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1952–2002¹ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Flag | |||||||||||||||||||||||

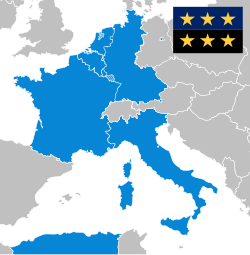

Founding members of the ECSC: Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany (Algeria was an integral part of the French Republic) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | International organisation | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Not applicable² | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | 11 (2002)³

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| President of the High Authority | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1952–1955 | Jean Monnet | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1955–1958 | René Mayer | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1958–1959 | Paul Finet | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1959–1963 | Piero Malvestiti | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1963–1967 | Rinaldo Del Bo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Signing (Treaty of Paris) | 18 April 1951 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• In force | 23 July 1952 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Merger | 1 July 1967 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23 July 2002¹ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

The ECSC was first proposed by French foreign minister Robert Schuman on 9 May 1950 as a way to prevent further war between France and Germany. He declared his aim was to "make war not only unthinkable but materially impossible"[3] which was to be achieved by regional integration, of which the ECSC was the first step. The Treaty would create a common market for coal and steel among its member states which served to neutralise competition between European nations over natural resources, particularly in the Ruhr.

The ECSC was overseen by four institutions: a High Authority composed of independent appointees, a Common Assembly composed of national parliamentarians, a Special Council composed of national ministers, and a Court of Justice. These would ultimately form the blueprint for today's European Commission, European Parliament, the Council of the European Union and the European Court of Justice.

The ECSC stood as a model for the communities set up after it by the Treaty of Rome in 1957, the European Economic Community and European Atomic Energy Community, with whom it shared its membership and some institutions. The 1967 Merger (Brussels) Treaty led all of ECSC's institutions to merge into the European Economic Community, but the ECSC retained its own independent legal personality. In 2002, the Treaty of Paris expired and the ECSC ceased to exist in any form, its activities fully absorbed by the European Community under the framework of the Amsterdam and Nice treaties.

History

As Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, Schuman was instrumental in turning French policy away from the Gaullist policy of permanent occupation or control of parts of German territory such as the Ruhr or the Saar. Despite stiff ultra-nationalist, Gaullist and communist opposition, the French Assembly voted a number of resolutions in favour of his new policy of integrating Germany into a community. The International Authority for the Ruhr changed in consequence.

Schuman declaration

The Schuman Declaration of 9 May 1950 (in 1985 declared "Europe Day" by the European Communities) occurred after two Cabinet meetings, when the proposal became French government policy. France was thus the first government to agree to surrender sovereignty in a supranational Community. That decision was based on a text, written and edited by Schuman's friend and colleague, the Foreign Ministry lawyer, professor Paul Reuter with the assistance of economist Jean Monnet and Schuman's Directeur de Cabinet, Bernard Clappier. It laid out a plan for a European Community to pool the coal and steel of its members in a common market.

Schuman proposed that "Franco-German production of coal and steel as a whole be placed under a common High Authority, within the framework of an organisation open to the participation of the other countries of Europe". Such an act was intended to help economic growth and cement peace between France and Germany, who were historic enemies. Coal and steel were vital resources needed for a country to wage war, so pooling those resources between two such enemies was seen as more than symbolic.[2][4] Schuman saw the decision of the French government on his proposal as the first example of a democratic and supranational Community, a new development in world history.[5][6] The plan was also seen by some, like Monnet, who crossed out Reuter's mention of "supranational" in the draft and inserted "federation", as a first step to a "European federation".[2][4]

The Schuman Declaration that created the ECSC had several distinct aims:

- It would mark the birth of a united Europe.

- It would make war between member states impossible.

- It would encourage world peace.

- It would transform Europe in a "step by step" process (building through sectoral supranational communities) leading to the unification of Europe democratically, unifying two political blocks separated by the Iron Curtain.

- It would create the world's first supranational institution.

- It would create the world's first international anti-cartel agency.

- It would create a common market across the Community.

- It would, starting with the coal and steel sector, revitalise the whole European economy by similar community processes.

- It would improve the world economy and the developing countries, such as those in Africa.[7]

Firstly, it was intended to prevent further war between France and Germany and other states[8] by tackling the root cause of war.[8] The ECSC was primarily conceived with France and Germany in mind: "The coming together of the nations of Europe requires the elimination of the age-old opposition of France and Germany. Any action taken must in the first place concern these two countries."[8] The coal and steel industries being essential for the production of munitions, Schuman believed that by uniting these two industries across France and Germany under an innovative supranational system that also included a European anti-cartel agency, he could "make war not only unthinkable but materially impossible".[9] Schuman had another aim: "With increased resources Europe will be able to pursue the achievement of one of its essential tasks, namely, the development of the African continent."[8] Industrial cartels tended to impose "restrictive practices"[8] on national markets, whereas the ECSC would ensure the increased production necessary for their ambitions in Africa.

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of the European Union |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Timeline

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Organisation

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Topics

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Political pressures

In West Germany, Schuman kept the closest contacts with the new generation of democratic politicians. Karl Arnold, the Minister President of North Rhine-Westphalia, the state that included the coal and steel producing Ruhr, was initially spokesman for German foreign affairs. He gave a number of speeches and broadcasts on a supranational coal and steel community at the same time as Robert Schuman began to propose this Community in 1948 and 1949. The Social Democratic Party of Germany (German: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, SPD), in spite of support from unions and other socialists in Europe, decided it would oppose the Schuman plan. Kurt Schumacher's personal distrust of France, capitalism, and Konrad Adenauer aside, he claimed that a focus on integrating with a "Little Europe of the Six" would override the SPD's prime objective of German reunification and thus empower ultra-nationalist and Communist movements in democratic countries. He also thought the ECSC would end any hopes of nationalising the steel industry and lock in a Europe of "cartels, clerics and conservatives".[10] Younger members of the party like Carlo Schmid, were, however, in favor of the Community and pointed to the long socialist support for the supranational idea.

In France, Schuman had gained strong political and intellectual support from all sections of the nation and many non-communist parties. Notable amongst these were ministerial colleague Andre Philip, president of the Foreign Relations Committee Edouard Bonnefous, and former prime minister, Paul Reynaud. Projects for a coal and steel authority and other supranational communities were formulated in specialist subcommittees of the Council of Europe in the period before it became French government policy. Charles de Gaulle, who was then out of power, had been an early supporter of "linkages" between economies, on French terms, and had spoken in 1945 of a "European confederation" that would exploit the resources of the Ruhr. However, he opposed the ECSC as a faux (false) pooling ("le pool, ce faux semblant") because he considered it an unsatisfactory "piecemeal approach" to European unity and because he considered the French government "too weak" to dominate the ECSC as he thought proper.[11] De Gaulle also felt that the ECSC had insufficient supranational authority because the Assembly was not ratified by a European referendum and he did not accept Raymond Aron's contention that the ECSC was intended as a movement away from United States domination. Consequently, de Gaulle and his followers in the RPF voted against ratification in the lower house of the French Parliament.[11]

Despite these attacks and those from the extreme left, the ECSC found substantial public support, and so it was established. It gained strong majority votes in all eleven chambers of the parliaments of the Six, as well as approval among associations and European public opinion. In 1950, many had thought another war was inevitable. The steel and coal interests, however, were quite vocal in their opposition. The Council of Europe, created by a proposal of Schuman's first government in May 1948, helped articulate European public opinion and gave the Community idea positive support.

The UK Prime Minister Clement Attlee opposed Britain joining the proposed European Coal and Steel Community, saying that he 'would not accept the [UK] economy being handed over to an authority that is utterly undemocratic and is responsible to nobody.' [12][13]

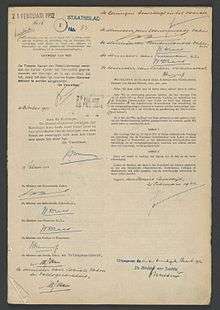

Treaties

The 100-article Treaty of Paris, which established the ECSC, was signed on 18 April 1951 by "the inner six": France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg (Benelux). The ECSC was the first international organisation to be based on supranational principles[2] and was, through the establishment of a common market for coal and steel, intended to expand the economies, increase employment, and raise the standard of living within the Community. The market was also intended to progressively rationalise the distribution of high level production whilst ensuring stability and employment. The common market for coal was opened on 10 February 1953, and for steel on 1 May 1953.[14] Upon taking effect, the ECSC gradually replaced the International Authority for the Ruhr.[15]

On 11 August 1952, the United States was the first non-ECSC member to recognise the Community and stated it would now deal with the ECSC on coal and steel matters, establishing its delegation in Brussels. Monnet responded by choosing Washington, D.C. as the site of the ECSC's first external presence. The headline of the delegation's first bulletin read "Towards a Federal Government of Europe".[16]

Six years after the Treaty of Paris, the Treaties of Rome were signed by the six ECSC members, creating the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or Euratom). These Communities were based, with some adjustments, on the ECSC. The Treaties of Rome were to be in force indefinitely, unlike the Treaty of Paris, which was to expire after fifty years. These two new Communities worked on the creation of a customs union and nuclear power community respectively.[2] The Rome treaties were hurried through just before de Gaulle was given emergency powers and proclaimed the Fifth Republic. Despite his efforts to "chloroform" the Communities, their fields rapidly expanded and the EEC became the most important tool for political unification, overshadowing the ECSC.[2]

Merger and expiration

Despite being separate legal entities, the ECSC, EEC and Euratom initially shared the Common Assembly and the European Court of Justice, although the Councils and the High Authority/Commissions remained separate. To avoid duplication, the Merger Treaty merged these separate bodies of the ECSC and Euratom with the EEC. The EEC later became one of the three pillars of the present day European Union.[2]

The Treaty of Paris was frequently amended as the EC and EU evolved and expanded. With the treaty due to expire in 2002, debate began at the beginning of the 1990s on what to do with it. It was eventually decided that it should be left to expire. The areas covered by the ECSC's treaty were transferred to the Treaty of Rome and the financial loose ends and the ECSC research fund were dealt with via a protocol of the Treaty of Nice. The treaty finally expired on 23 July 2002.[4] That day, the ECSC flag was lowered for the final time outside the European Commission in Brussels and replaced with the EU flag.[17]

Timeline of treaties

| Signed: In force: Document: |

1947 1947 Dunkirk Treaty |

1948 1948 Brussels Treaty |

1951 1952 Paris Treaty |

1954 1955 Modified Brussels Treaty |

1957 1958 Rome & Euratom treaties |

1965 1967 Merger Treaty |

1975 1976 Council Agreement on TREVI |

1986 1987 Single European Act |

1985/90 1995 Schengen Treaty & Convention |

1992 1993 Maastricht Treaty |

1997 1999 Amsterdam Treaty |

2001 2003 Nice Treaty |

2007 2009 Lisbon Treaty |

|||

| Three pillars of the European Union: | ||||||||||||||||

| European Communities (with common institutions) |

||||||||||||||||

| European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) | ||||||||||||||||

| European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) | Treaty expired in 2002 | European Union (EU) | ||||||||||||||

| European Economic Community (EEC) | European Community (EC) | |||||||||||||||

| Schengen Rules | ||||||||||||||||

| Terrorism, Radicalism, Extremism and Violence Internationally (TREVI) | Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) |

Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters (PJCC) | ||||||||||||||

| European Political Cooperation (EPC) | Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) | |||||||||||||||

| Franco-British alliance | Western Union (WU) (Cannibalised militarily by NATO in 1951) |

Western European Union (WEU) (Social and cultural activities transferred to the Council of Europe in 1960) |

||||||||||||||

| Treaty terminated in 2011 | ||||||||||||||||

Institutions

The institutions of the ECSC were the High Authority, the Common Assembly, the Special Council of Ministers and the Court of Justice. A Consultative Committee was established alongside the High Authority, as a fifth institution representing civil society. This was the first international representation of consumers in history. These institutions were merged in 1967 with those of the European Community, which then governed the ECSC,[14] except for the Committee, which continued to be independent until the expiration of the Treaty of Paris in 2002.[18]

The Treaty stated that the location of the institutions would be decided by common accord of the members, yet the issue was hotly contested. As a temporary compromise, the institutions were provisionally located in the City of Luxembourg, despite the Assembly being based in Strasbourg.[19]

High Authority

The High Authority (the predecessor to the European Commission) was a nine-member executive body which governed the Community. The Authority consisted of nine members in office for a term of six years. Eight of these members were appointed by the governments of the six signatories.[20] These eight members then themselves appointed a ninth person to be President of the High Authority.[14]

Despite being appointed by agreement of national governments acting together, the members were to pledge not to represent their national interest, but rather took an oath to defend the general interests of the Community as a whole. Their independence was aided by members being barred from having any occupation outside the Authority or having any business interests (paid or unpaid) during their tenure and for three years after they left office.[14] To further ensure impartiality, one third of the membership was to be renewed every two years (article 10).

The Authority's principal innovation was its supranational character. It had a broad area of competence to ensure the objectives of the treaty were met and that the common market functioned smoothly. The High Authority could issue three types of legal instruments: Decisions, which were entirely binding laws; Recommendations, which had binding aims but the methods were left to member states; and Opinions, which had no legal force.[14]

Up to the merger in 1967, the authority had five Presidents followed by an interim President serving for the final days.[21]

| No. | President | Took office | Left office | Time in office | Constituency | Authority | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jean Monnet (1888–1979) | 10 August 1952 | 3 June 1955 | 2 years, 297 days | Monnet Authority | ||

| 2 | René Mayer (1895–1972) | 3 June 1955 | 13 January 1958 | 2 years, 224 days | Mayer Authority | ||

| 3 | Paul Finet (1897–1965) | 13 January 1958 | 15 September 1959 | 1 year, 245 days | Finet Authority | ||

| 4 | Piero Malvestiti (1899–1964) | 15 September 1959 | 22 October 1963 | 4 years, 37 days | Malvestiti Authority | ||

| 5 | Rinaldo Del Bo (1916–1991) | 22 October 1963 | 8 March 1967 | 3 years, 137 days | Del Bo Authority | ||

| – | Albert Coppé (1911–1999) Acting | 1 March 1967 | 5 July 1967 | 126 days | Coppé Authority |

Other institutions

The Common Assembly (which later became the European Parliament) was composed of 78 representatives and exercised supervisory powers over the executive High Authority. The Common Assembly representatives were to be national MPs delegated each year by their Parliaments to the Assembly or directly elected "by universal suffrage" (article 21), though in practice it was the former, as there was no requirement for elections until the Treaties of Rome and no actual election until 1979, as Rome required agreement in the Council on the electoral system first. However, to emphasise that the chamber was not a traditional international organisation composed of representatives of national governments, the Treaty of Paris used the term "representatives of the peoples".[14] The Assembly was not originally specified in the Schuman Plan because it was hoped the Community would use the institutions (Assembly, Court) of the Council of Europe. When this became impossible because of British objections, separate institutions had to be created. The Assembly was intended as a democratic counter-weight and check to the High Authority, to advise but also to have power to sack the Authority for incompetence, injustice, corruption or fraud. The first President (akin to a Speaker) was Paul-Henri Spaak.[22]

The Special Council of Ministers (equivalent to the current Council of the European Union) was composed of representatives of national governments. The Presidency was held by each state for a period of three months, rotating between them in alphabetical order. One of its key aspects was the harmonisation of the work of the High Authority and that of national governments, which were still responsible for the state's general economic policies. The Council was also required to issue opinions on certain areas of work of the High Authority.[14] Issues relating only to coal and steel were in the exclusive domain of the High Authority, and in these areas the Council (unlike the modern Council) could only act as a scrutiny on the Authority. However, areas outside coal and steel required the consent of the Council.[23]

The Court of Justice was to ensure the observation of ECSC law along with the interpretation and application of the Treaty. The Court was composed of seven judges, appointed by common accord of the national governments for six years. There were no requirements that the judges had to be of a certain nationality, simply that they be qualified and that their independence be beyond doubt. The Court was assisted by two Advocates General.[14]

The Consultative Committee (similar to the Economic and Social Committee) had between 30 and 50 members equally divided between producers, workers, consumers and dealers in the coal and steel sector. Again, there were no national quotas, and the treaty required representatives of European associations to organise their own democratic procedures. They were to establish rules to make their membership fully representative for democratic organised civil society. Membership were appointed for two years and were not bound by any mandate or instruction of the organisations which appointed them. The Committee had a plenary assembly, bureau and president. Again, the required democratic procedures were not introduced and nomination of these members remained in the hands of national ministers. The High Authority was obliged to consult the Committee in certain cases where it was appropriate and to keep it informed.[14] The Consultative Committee remained separate (despite the merger of the other institutions) until 2002, when the Treaty expired and its duties were taken over by the Economic and Social Committee (ESC). Despite its independence, the Committee did cooperate with the ESC when they were consulted on the same issue.[18]

Achievements and failures

Its mission (article 2) was general: to "contribute to the expansion of the economy, the development of employment and the improvement of the standard of living" of its citizens. The Community had little effect on coal and steel production, which was influenced more by global trends. Trade between members did increase (tenfold for steel) which saved members' money by not having to import resources from the United States. The High Authority also issued 280 modernization loans to the industry which helped the industry to improve output and reduce costs. Costs were further reduced by the abolition of tariffs at borders.[24]

Among the ECSC's greatest achievements are those on welfare issues. Some mines, for example, were clearly unsustainable without government subsidies. Some miners had extremely poor housing. Over 15 years it financed 112,500 flats for workers, paying US$1,770 per flat, enabling workers to buy a home they could not have otherwise afforded. The ECSC also paid half the occupational redeployment costs of those workers who have lost their jobs as coal and steel facilities began to close down. Combined with regional redevelopment aid the ECSC spent $150 million creating 100,000 jobs, a third of which were for unemployed coal and steel workers. The welfare guarantees invented by the ECSC were extended to workers outside the coal and steel sector by some of its members.[24]

Far more important than creating Europe's first social and regional policy, it is argued that the ECSC introduced European peace. It involved the continent's first European tax. This was a flat tax, a levy on production with a maximum rate of one percent. Given that the European Community countries are now experiencing the longest period of peace in more than seventy years,[25] this has been described as the cheapest tax for peace in history. Another world war, or "world suicide" as Schuman called this threat in 1949, was avoided. In October 1953 Schuman said that the possibility of another European war had been eliminated. Reasoning had to prevail among member states.

However the ECSC failed to achieve several fundamental aims of the Treaty of Paris. It was hoped the ECSC would prevent a resurgence of large coal and steel groups such as the Konzerne, which helped Adolf Hitler rise to power. In the Cold War trade-offs, the cartels and major companies re-emerged, leading to apparent price fixing (another element that was meant to be tackled). With a democratic supervisory system the worst aspects of past abuse were avoided with the anti-cartel powers of the Authority, the first international anti-cartel agency in the world. Efficient firms were allowed to expand into a European market without undue domination. Oil, gas, electricity became natural competitors to coal and also broke cartel powers. Furthermore, with the move to oil, the Community failed to define a proper energy policy. The Euratom treaty was largely stifled by de Gaulle and the European governments refused the suggestion of an Energy Community involving electricity and other vectors that was suggested at Messina in 1955. In a time of high inflation and monetary instability ECSC also fell short of ensuring an upward equalisation of pay of workers within the market. These failures could be put down to overambition in a short period of time, or that the goals were merely political posturing to be ignored. It has been argued that the greatest achievements of the European Coal and Steel Community lie in its revolutionary democratic concepts of a supranational Community.[24]

See also

- Energy Community

- Energy policy of the European Union

- Flag of the European Coal and Steel Community

- History of the European Union

- History of the Ruhr District

- Industrial plans for Germany

- Monnet plan

- Schuman Declaration

- Supranationalism

- Supranational union

References

- "Treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community, ECSC Treaty, Summary". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- "The European Communities". CVCE. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- "EUROPA - The Schuman Declaration – 9 May 1950". europa.eu.

- "Treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community, ECSC Treaty". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- "Schuman Project". schuman.info.

- "Schuman Project". schuman.info.

- "Schuman Project". schuman.info.

- Declaration of 9 May 1950 Fondation Robert Schuman

- Robert Schuman's proposal of 9 May 1950 Schuman Project

- Orlow, D. (2002). Common Destiny: A Comparative History of the Dutch, French, and German Social Democratic Parties, 1945–1969. Berghahn Books. pp. 168–172. ISBN 978-1571811851.

- Chopra, H.S. (1974). De Gaulle and European unity. Abhinav Publications. pp. 28–33.

- https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-britain-eu-timeline/a-long-and-winding-road-the-uk-journey-in-and-out-of-the-eu-idUKKBN1ZT2F3. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- McCormick, J. (2011). European Union Politics, p.73.

- "The Treaties establishing the European Communities". CVCE. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- Office of the US High Commissioner for Germany Office of Public Affairs, Public Relations Division, APO 757, US Army, January 1952 "Plans for terminating international authority for the Ruhr", pp. 61–62

- Washington Delegation History Archived 25 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Delegation of the European Commission to the United States

- "Ceremony to mark the expiry of the ECSC Treaty (Brussels, 23 July 2002)". CVCE. 23 July 2002. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- "European Economic and Social Committee and ECSC Consultative Committee". CVCE. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- "The seats of the institutions of the European Union". CVCE. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- Dedman, Martin (2010). The Origins and Development of the European Union. 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN: Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-415-43561-1.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Members of the High Authority of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC)". CVCE. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- "Negotiations on the ECSC Treaty : Multilateral negotiations". CVCE. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- "Council of the European Union". CVCE. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- Mathieu, Gilbert (9 May 1970). "The history of the ECSC: good times and bad". Le Monde. France, accessed on CVCE. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- Price, David H. "Mr". Shuman project. info.schuman.info. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

Further reading

- Grin, Gilles (2003). The Battle of the Single European Market: Achievements and Economic Thought, 1945–2000. Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7103-0938-9.

- Hitchcock, William I. (1998). France Restored: Cold War Diplomacy and the Quest for Leadership in Europe, 1944–1954. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4747-X.

- Maas, Willem (2007). Creating European Citizens. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-5485-6.

- Schuman or Monnet? The real Architect of Europe. Robert Schuman's speeches and texts on the origin, purpose and future of Europe. Bron. ISBN 0-9527276-4-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to European Coal and Steel Community. |

- Documents of the European Coal and Steel Community are consultable at the Historical Archives of the EU in Florence

- rtsp://rtsppress.cec.eu.int/Archive/video/mpeg/i000679/i000679.rm (insert address into RealPlayer) Common Destiny, a period film explaining the Coal and Steel Community, Europa (web portal)

- Treaty constituting the European Coal and Steel Community, CVCE

- Schuman info

- The institutions of the European Coal and Steel Community, CVCE

- France, Germany and the Struggle for the War-making Natural Resources of the Rhineland, American University

- Ruhr Delegation of the United States of America, Council of Foreign Ministers American Embassy Moscow, 24 March 1947, Truman Library

.jpg)