Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (/ˈkɪsɪndʒər/;[1] German: [ˈkɪsɪŋɐ]; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger; May 27, 1923) is an American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presidential administrations of Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford.[2] A Jewish refugee who fled Nazi Germany with his family in 1938, he became National Security Advisor in 1969 and U.S. Secretary of State in 1973. For his actions negotiating a ceasefire in Vietnam, Kissinger received the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize under controversial circumstances, with two members of the committee resigning in protest.[3]

Henry Kissinger | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| 56th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office September 22, 1973 – January 20, 1977 | |

| President | Richard Nixon Gerald Ford |

| Deputy | Kenneth Rush Robert Ingersoll Charles Robinson |

| Preceded by | William Rogers |

| Succeeded by | Cyrus Vance |

| 8th United States National Security Advisor | |

| In office January 20, 1969 – November 3, 1975 | |

| President | Richard Nixon Gerald Ford |

| Deputy | Richard Allen Alexander Haig Brent Scowcroft |

| Preceded by | Walt Rostow |

| Succeeded by | Brent Scowcroft |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Heinz Alfred Kissinger May 27, 1923 Fürth, Weimar Republic |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Ann Fleischer (m. 1949; div. 1964) Nancy Maginnes (m. 1974) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | City University of New York, City College Harvard University (AB, AM, PhD) |

| Civilian awards | Nobel Peace Prize |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1943–1946 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 970th Counter Intelligence Corps |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Military awards | |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

|

Schools

|

|

Principles

|

|

History

|

|

People

|

|

Parties

|

|

Think tanks

|

|

Other organizations

|

|

Media

|

|

Variants and movements

|

|

See also

|

|

|

A practitioner of Realpolitik,[4] Kissinger played a prominent role in United States foreign policy between 1969 and 1977. During this period, he pioneered the policy of détente with the Soviet Union, orchestrated the opening of relations with the People's Republic of China, engaged in what became known as shuttle diplomacy in the Middle East to end the Yom Kippur War, and negotiated the Paris Peace Accords, ending American involvement in the Vietnam War. Kissinger has also been associated with such controversial policies as U.S. involvement in the 1973 Chilean military coup, a "green light" to Argentina's military junta for their Dirty War, and U.S. support for Pakistan during the Bangladesh War despite the genocide being perpetrated by his allies.[5] After leaving government, he formed Kissinger Associates, an international geopolitical consulting firm. Kissinger has written over one dozen books on diplomatic history and international relations.

Kissinger remains a controversial and polarizing figure in American politics, both condemned as an alleged war criminal by many journalists, political activists, and human rights lawyers,[4][6][7][8] as well as venerated as a highly effective U.S. Secretary of State by many prominent international relations scholars.[9]

Early life and education

Kissinger was born Heinz Alfred Kissinger in Fürth, Bavaria, Germany in 1923 to a family of German Jews.[10] His father, Louis Kissinger (1887–1982), was a schoolteacher. His mother, Paula (Stern) Kissinger (1901–1998), from Leutershausen, was a homemaker. Kissinger has a younger brother, Walter Kissinger (born 1924). The surname Kissinger was adopted in 1817 by his great-great-grandfather Meyer Löb, after the Bavarian spa town of Bad Kissingen.[11] In his youth, Kissinger enjoyed playing soccer, and played for the youth wing of his favorite club, SpVgg Fürth, which was one of the nation's best clubs at the time.[12] In 1938, when Kissinger was 15 years old, he fled Germany with his family as a result of Nazi persecution. His family briefly emigrated to London, England, before arriving in New York on September 5.

Kissinger spent his high school years in the Washington Heights section of Upper Manhattan as part of the German Jewish immigrant community that resided there at the time. Although Kissinger assimilated quickly into American culture, he never lost his pronounced German accent, due to childhood shyness that made him hesitant to speak.[13][14] Following his first year at George Washington High School, he began attending school at night and worked in a shaving brush factory during the day.[13]

Following high school, Kissinger enrolled in the City College of New York, studying accounting. He excelled academically as a part-time student, continuing to work while enrolled. His studies were interrupted in early 1943, when he was drafted into the U.S. Army.[15]

Army experience

Kissinger underwent basic training at Camp Croft in Spartanburg, South Carolina. On June 19, 1943, while stationed in South Carolina, at the age of 20 years, he became a naturalized U.S. citizen. The army sent him to study engineering at Lafayette College, Pennsylvania, but the program was canceled, and Kissinger was reassigned to the 84th Infantry Division. There, he made the acquaintance of Fritz Kraemer, a fellow Jewish immigrant from Germany who noted Kissinger's fluency in German and his intellect, and arranged for him to be assigned to the military intelligence section of the division. Kissinger saw combat with the division, and volunteered for hazardous intelligence duties during the Battle of the Bulge.[16]

During the American advance into Germany, Kissinger, only a private, was put in charge of the administration of the city of Krefeld, owing to a lack of German speakers on the division's intelligence staff. Within eight days he had established a civilian administration.[17] Kissinger was then reassigned to the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC), where he became a CIC Special Agent holding the enlisted rank of sergeant. He was given charge of a team in Hanover assigned to tracking down Gestapo officers and other saboteurs, for which he was awarded the Bronze Star.[18] In June 1945, Kissinger was made commandant of the Bensheim metro CIC detachment, Bergstrasse district of Hesse, with responsibility for de-Nazification of the district. Although he possessed absolute authority and powers of arrest, Kissinger took care to avoid abuses against the local population by his command.[19]

In 1946, Kissinger was reassigned to teach at the European Command Intelligence School at Camp King and, as a civilian employee following his separation from the army, continued to serve in this role.[20][21]

Academic career

.jpg)

Henry Kissinger received his AB degree summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa[22] in political science from Harvard College in 1950, where he lived in Adams House and studied under William Yandell Elliott.[23] His senior undergraduate thesis, titled The Meaning of History: Reflections on Spengler, Toynbee and Kant, was over 400 pages long.[24][25] He received his MA and PhD degrees at Harvard University in 1951 and 1954, respectively. In 1952, while still a graduate student at Harvard, he served as a consultant to the director of the Psychological Strategy Board.[26]

His doctoral dissertation was titled Peace, Legitimacy, and the Equilibrium (A Study of the Statesmanship of Castlereagh and Metternich).[27] In his PhD dissertation, Kissinger first introduced the concept of "legitimacy", which he defined as: "Legitimacy as used here should not be confused with justice. It means no more than an international agreement about the nature of workable arrangements and about the permissible aims and methods of foreign policy".[28] An international order accepted by all of the major powers is "legitimate" whereas an international order not accepted by one or more of the great powers is "revolutionary" and hence dangerous.[29] Thus, when after the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the leaders of Britain, France, Austria, Prussia and Russia agreed to co-operate in the Concert of Europe to preserve the peace, in Kissinger's viewpoint this international system was "legitimate" because it was accepted by the leaders of all five of the Great Powers of Europe. Notably, Kissinger's primat der aussenpolitik approach to diplomacy took it for granted that as long as the decision-makers in the major states were willing to accept the international order, then it is "legitimate" with questions of public opinion and morality dismissed as irrelevant.[30]

Kissinger remained at Harvard as a member of the faculty in the Department of Government and, with Robert R. Bowie, co-founded the Center for International Affairs in 1958 where he served as associate director. In 1955, he was a consultant to the National Security Council's Operations Coordinating Board.[26] During 1955 and 1956, he was also study director in nuclear weapons and foreign policy at the Council on Foreign Relations. He released his book Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy the following year.[31] The book which was a critique of the Eisenhower Administration's "massive retaliation" nuclear doctrine caused much controversy at the time with its advocacy of using tactical nuclear weapons on a regular basis to win wars.[32]

From 1956 to 1958 he worked for the Rockefeller Brothers Fund as director of its Special Studies Project.[26] He was director of the Harvard Defense Studies Program between 1958 and 1971. He was also director of the Harvard International Seminar between 1951 and 1971. Outside of academia, he served as a consultant to several government agencies and think tanks, including the Operations Research Office, the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, Department of State, and the RAND Corporation.[26]

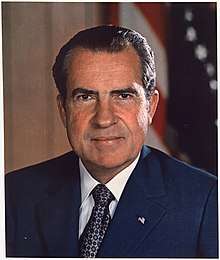

Keen to have a greater influence on U.S. foreign policy, Kissinger became foreign policy advisor to the presidential campaigns of Nelson Rockefeller, supporting his bids for the Republican nomination in 1960, 1964, and 1968.[33] Kissinger first met Richard Nixon at a party hosted by Clare Booth Luce in 1967, saying that he found him more "thoughtful" than what he expected.[34] During the Republican primaries in 1968, Kissinger again served as the foreign policy adviser to Rockefeller and in July 1968 called Nixon "the most dangerous of all the men running to have as president".[34] Initially upset when Nixon won the Republican nomination, the ambitious Kissinger soon changed his mind about Nixon and contacted a Nixon campaign aide, Richard Allen, to state he was willing to do anything to help Nixon win.[35] After Nixon became president in January 1969, Kissinger was appointed as National Security Advisor.

Foreign policy

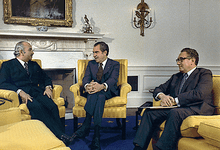

Kissinger served as National Security Advisor and Secretary of State under President Richard Nixon, and continued as Secretary of State under Nixon's successor Gerald Ford.[36] On Nixon's last full day in office, in the meeting where he informed Ford of his intention to resign the next day, he advised Ford that he felt it was very important that he keep Kissinger in his new administration, to which Ford agreed.[37]

The relationship between Nixon and Kissinger was unusually close, and has been compared to the relationships of Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House, or Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Hopkins.[38] In all three cases, the State Department was relegated to a backseat role in developing foreign policy.[39] Historian David Rothkopf has looked at the personalities of Nixon and Kissinger:

- They were a fascinating pair. In a way, they complemented each other perfectly. Kissinger was the charming and worldly Mr. Outside who provided the grace and intellectual-establishment respectability that Nixon lacked, disdained and aspired to. Kissinger was an international citizen. Nixon very much a classic American. Kissinger had a worldview and a facility for adjusting it to meet the times, Nixon had pragmatism and a strategic vision that provided the foundations for their policies. Kissinger would, of course, say that he was not political like Nixon—but in fact he was just as political as Nixon, just as calculating, just as relentlessly ambitious....these self-made men were driven as much by their need for approval and their neuroses as by their strengths.[40]

A proponent of Realpolitik, Kissinger played a dominant role in United States foreign policy between 1969 and 1977. In that period, he extended the policy of détente. This policy led to a significant relaxation in US–Soviet tensions and played a crucial role in 1971 talks with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai. The talks concluded with a rapprochement between the United States and the People's Republic of China, and the formation of a new strategic anti-Soviet Sino-American alignment. He was jointly awarded the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize with Lê Đức Thọ for helping to establish a ceasefire and U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam. The ceasefire, however, was not durable.[41] Thọ declined to accept the award[42] and Kissinger appeared deeply ambivalent about it (donating his prize money to charity, not attending the award ceremony and later offering to return his prize medal[40]). As National Security Advisor, in 1974 Kissinger directed the much-debated National Security Study Memorandum 200.

Kissinger and Nixon shared a penchant for secrecy and conducted numerous "backchannel" negotiations that excluded State Department experts. One such years-long backchannel was conducted through the Soviet Ambassador to the United States, Anatoly Dobrynin. One historian argues that Kissinger formed such a strong "bond of affection, trust, and mutual interest" with the ambassador that he came to see U.S.-Soviet relations as holding exaggerated significance. He typically met with or talked to Dobrynin about four times a week, and they had a direct line to each other's offices.[43]

Arrival in Washington

Nixon gave Kissinger the freedom to assemble his own team in 1969 in order to "revitalize" the National Security Council.[44] Kissinger's team consisted of Colonel Alexander Haig, Morton Halperin, and Anthony Lake.[44] Right from the start, Kissinger started to exclude both the Secretary of State William P. Rogers and the Defense Secretary Melvin Laird from the decision-making process.[44] Kissinger had low opinion of Washington bureaucracy, writing in his PhD dissertation A World Restored that: "The essence of bureaucracy is its quest for safety; its success is calculability. Profound policy thrives on perpetual creation, on a constant redefinition of goals...Bureaucracies are designed to execute, not conceive".[44] Kissinger as National Security Adviser saw a chance to put his theories in action, favoring a strategy of being unpredictable in an attempt to change the diplomatic equilibrium in favor of the United States.[44]

Détente and the opening to China

Kissinger sought to place diplomatic pressure on the Soviet Union by playing the "China card". Kissinger initially had little interest in China when began his work as National Security Adviser in 1969, and the driving force being the rapprochement with China was Nixon.[45] Out of fear of the China Lobby that he himself wanted once cultivated in the 1950s, Nixon wanted to keep the negotiations with China secret.[46] During his visit to Pakistan (which was uniquely an ally of both the United States and China) in August 1969, Nixon asked General Yahya Khan to pass on a message to Mao Zedong that he wanted an "opening" to China.[47] Shortly afterwards, Kissinger asked that the back channel to China work only through messages personally sent from Pakistani ambassador in Washington, Agha Hilaly, to Yahya Khan.[48] The Pakistani back channel to China worked very slowly not least because Yahya Khan expected to be paid bribes for his help, and only six months later in February 1970 did Yahya Khan pass on a message to Nixon from Mao expressing interest.[49] In his memoirs Kissinger portrayed Yahya Khan as an honorable soldier who never asked for any rewards for his work as an intermediary, but in fact he demanded extensive American military supplies and support for Pakistan's long running feud with India as the price of his help.[50] When Chiang Ching-kuo, the son and heir apparent of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek arrived in Washington in April 1970 for a visit, both Nixon and Kissinger promised him that they would never abandon Taiwan or make any compromises with Mao Zedong, although Nixon did speak vaguely of his wish to improve relations with the People's Republic.[51] In November 1970, Yahya Khan visited Beijing to meet Mao, and was informed: "In order to discuss the subject of vexation of China's territory called Taiwan, a special envoy from President Nixon would be welcome in Beijing".[52]

Kissinger made two trips to the People's Republic of China in July and October 1971 (the first of which was made in secret) to confer with Premier Zhou Enlai, then in charge of Chinese foreign policy.[53] Unlike Mao who spoke no language other than Mandarin, Zhou spoke French (the traditional language of diplomacy) at a conversational level and it was he who usually handled relations with foreigners. According to Kissinger's book, The White House Years and On China, the first secret China trip was arranged through Pakistani and Romanian diplomatic and Presidential involvement, as there were no direct communication channels between the states.[54] During his visit to Beijing, the main issue turned out to be Taiwan as Zhou demanded the United States recognize that Taiwan was a legitimate part of the People's Republic of China, pull out U.S. forces out of Taiwan, and end military support for the Kuomintang regime, saying that once the Taiwan issue was resolved, there would be no outstanding problems in Sino-American relations.[55] Kissinger gave away by promising to pull U.S. forces out of Taiwan, saying two-thirds would be pulled out when the Vietnam war ended and the rest to be pulled out as Sino-American relations improved.[56]

In October 1971, at the same time Kissinger was making his second trip to the People's Republic, the issue of which Chinese government deserved to be represented in the United Nations came up again.[57] Out of concern to be not be seen abandoning an ally, the United States tried to promote a compromise under which both Chinese regimes would be UN members, although Kissinger called it "an essentially doomed rearguard action".[58] At the same time that the American ambassador to the UN, George H. W. Bush, was lobbying for the "two Chinas" formula, Kissinger was removing favorable references to Taiwan from a speech that Rogers was preparing as he expected the Republic of China to be expelled from the UN.[59] During his second visit to Beijing, Kissinger told Zhou that accordingly to a public opinion poll that 62% of Americans wanted Taiwan to remain an UN member and asked him to consider the "two Chinas" compromise to avoid offending American public opinion.[60] Zhou responded with his claim that the People's Republic was the legitimate government of all China and no compromise was possible with the Taiwan issue.[61] When Kissinger said that United States could not totally sever ties with Chiang who had been an ally in World War II, leading Zhou to cynically say: "That is still your old saying-you don't want to cast aside old friends. But you have already cast aside many old friends. Chiang Kai-shek was even an older friend of ours than yours".[62]

Kissinger told Nixon that Bush was "too soft and not sophisticated" enough to properly represent the United States at the UN and expressed no anger when the UN General Assembly voted to expel Taiwan and give China's seat on the UN Security Council to the People's Republic.[63] Bush later said about the expulsion of Taiwan: "What was hard...to understand was Henry's telling me he was 'disappointed' by the final outcome of the Taiwan vote...given the fact that we were saying one thing in New York and doing another in Washington, that outcome was inevitable".[64] The stubbornness of Chiang, who just as much as Mao believed in "one China" ensured the defeat of the "two Chinas" compromise; by 1971, the general consensus around the world was that Chiang was delusional in believing that he would one day return in triumph to the mainland to take back control from the Communist "rebels" who had defeated him in 1949 and it was absurd to have the Republic of China which only controlled Taiwan to be representing China at the UN.[65]

His trips paved the way for the groundbreaking 1972 summit between Nixon, Zhou, and Communist Party of China Chairman Mao Zedong, as well as the formalization of relations between the two countries, ending 23 years of diplomatic isolation and mutual hostility. The result was the formation of a tacit strategic anti-Soviet alliance between China and the United States.

While Kissinger's diplomacy led to economic and cultural exchanges between the two sides and the establishment of Liaison Offices in the Chinese and American capitals, with serious implications for Indochinese matters, full normalization of relations with the People's Republic of China would not occur until 1979, because the Watergate scandal overshadowed the latter years of the Nixon presidency and because the United States continued to recognize the Republic of China on Taiwan.

Vietnam War

Kissinger's involvement in Indochina started prior to his appointment as National Security Adviser to Nixon. While still at Harvard, he had worked as a consultant on foreign policy to both the White House and State Department. Kissinger says that "In August 1965 ... [Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr.], an old friend serving as Ambassador to Saigon, had asked me to visit Vietnam as his consultant. I toured Vietnam first for two weeks in October and November 1965, again for about ten days in July 1966, and a third time for a few days in October 1966 ... Lodge gave me a free hand to look into any subject of my choice". He became convinced of the meaninglessness of military victories in Vietnam, "... unless they brought about a political reality that could survive our ultimate withdrawal".[66] In a 1967 peace initiative, he would mediate between Washington and Hanoi.

Nixon had been elected in 1968 on the promise of achieving "peace with honor" and ending the Vietnam War. By promising to continue the peace talks which Johnson began in May 1968 in Paris, Nixon admitted that he had ruled out "a military victory" in Vietnam.[67] Nixon wanted a diplomatic settlement similar to the armistice of Panmunjom that ended the Korean War and frequently stated in private he had no intention of being "the first president of the United States to lose a war".[67] To force the North Vietnamese to sign an armistice, Nixon favored a two-pronged approach of the "madman theory" of seeking to act rashly to intimidate the North Vietnamese while at the same time trying using the strategy of "linkage" to improve relations with the Soviet Union and China in order to persuade both these nations to stop sending arms to North Vietnam..[68] In office, and assisted by Kissinger, Nixon implemented a policy of Vietnamization that aimed to gradually withdraw U.S. troops while expanding the combat role of the South Vietnamese Army so that it would be capable of independently defending its government against the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam, a Communist guerrilla organization, and the North Vietnamese army (Vietnam People's Army or PAVN).

In an article published in Foreign Affairs in January 1969, Kissinger criticized General William Westmoreland's attrition strategy because the Vietnamese Communists were willing to accept far higher losses on the battlefield than the United States and could therefore "win" as long as they did not "lose" by merely keeping the war going.[69] In the same article, he argued that losses endured by the Vietnamese Communists in the Tet Offensive were meaningless as the Tet Offensive had turned American public opinion against the war, ruling out the possibility of a military solution, and the best that could be done now was to negotiate the most favorable peace settlement at the Paris peace talks.[44] Kissinger, when he came into office in 1969 favored a negotiating strategy under which the United States and North Vietnam would sign an armistice and agreed to pull their troops out of South Vietnam while the South Vietnamese government and the Viet Cong were to agree to a coalition government.[69] Kissinger had doubts about Nixon's theory of "linkage", believing that this would give the Soviet Union leverage over the United States and unlike Nixon was less concerned about the ultimate fate of South Vietnam.[70] One of Kissinger's first acts as National Security Adviser in early 1969 was to seek opinions of the Vietnam experts within the CIA, the military and the State Department.[71] The lengthy volume that emerged contained a diverse collection of opinions with some stating the South Vietnamese were making "rapid strides" while others doubted that the government in Saigon would "ever constitute an effective political or military counter to the Vietcong".[71] The "bulls" estimated that American troops would need to fight on in Vietnam for 8.3 years before the South Vietnamese would be able to fight on their own while the "bears" estimated it take 13.4 years of American troops fighting in Vietnam before the South Vietnamese would be able to fight on their own.[71] Kissinger passed the volume on to Nixon with the comment that there was no consensus within the expert community with the implied conclusion that he should be free on his own without consulting the experts.[71]

In early 1969, Kissinger was opposed to the plans for Operation Menu, the bombing of Cambodia, fearing that Nixon was acting rashly with no plans for the diplomatic fall-out, but on 16 March 1969 Nixon at a meeting at the White House attended by Kissinger announced the bombing would start the next day.[72] As Congress was unlikely to grant approval to bombing Cambodia, Nixon decided to go ahead without Congressional approval and keep the bombings secret, a decision that several constitutional law experts argued was illegal.[73] In May 1969, the bombing was leaked to William M. Beecher of the New York Times who published an article about it, which infuriated Kissinger.[73] At the time, Kissinger told the FBI director J.E. Hoover "we will destroy whoever did this".[73] As a result, the phones of 13 members of Kissinger's staff were taped by the FBI without a warrant.[73] At the time, Kissinger portrayed himself to his friends at Harvard as a moderating force who was working to remove the United States from Vietnam, saying he did not want to end up like his predecessor W.W. Rostow, whose actions as National Security Adviser had caused him to be ostracized by the liberal American intelligentsia.[35]

As part of the "linkage" concept, Kissinger in March 1969 sent Cyrus Vance to Moscow with the message that if the Soviet Union pressured North Vietnam into a diplomatic settlement favorable to the United States, the reward would be concessions on the talks on limiting the nuclear arms race.[74] At the same time, Kissinger met with the Soviet ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin to warn him that Nixon was a dangerous man who wanted to escalate the Vietnam war.[75] Nixon and Kissinger played a "good cop-bad cop" routine with Dobrynin with Nixon acting the part of the petulant president at the end of his patience with North Vietnam while Kissinger acted as the reasonable diplomat anxious to improve relations with the Soviet Union, saying to Dobrynin in May 1969 that Nixon would "escalate the war" if the Soviet Union "didn't produce a settlement" in Vietnam.[76] At another meeting in 1969, Kissinger warned Dobrynin that "the train has just left the station and is now headed down the track", saying the Soviet Union better start pressuring North Vietnam now before Nixon did something truly reckless and dangerous.[75] The attempt at "linkage" failed as the Soviet Union did not pressure North Vietnam and instead Dobrynin told Kissinger that the Soviets wanted better relations with the United States regardless of the Vietnam war.[75] After the failure of the "linkage" attempt, Nixon became more open to the alternative strategy suggested by the Defense Secretary Melvin Laird who argued that the burden of the war should be shifted to the South Vietnamese, which was initially called "de-Americanization" and which Laird renamed Vietnamization because it sounded better.[77]

On 4 August 1969, Kissinger met secretly with Xuân Thủy at the Paris apartment of Jean Sainteny to discuss peace.[78] Kissinger repeated the American offer of "mutual withdrawal" of U.S and North Vietnamese forces from South Vietnam which Thủy rejected while Thủy demanded a new government in Saigon which Kissinger rejected.[78] Kissinger had a low opinion of North Vietnam, saying "I can't believe that a fourth-rate power like North Vietnam doesn't have a breaking point".[35] Kissinger was opposed to the strategy of Vietnamization, expressing some doubt about the ability of the ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam-i.e. the South Vietnamese Army) to hold the field, causing much tension with Defense Secretary Laird who was deeply committed to Vietnamization.[35] In September 1969, Kissinger in a memo advised Nixon against "de-escalation", saying that keeping U.S troops fighting in Vietnam "remains one of our few bargaining weapons".[35] In the same memo, Kissinger stated he was "deeply disturbed" that Nixon had started pulling out U.S. troops, saying that withdrawing the troops was like "salted peanuts" to the American people, "the more U.S troops come home, the more will be demanded", giving the advantage to the enemy who merely had to "wait us out".[35] Instead, he recommenced that the United States resume bombing North Vietnam and mine the coast.[35] Later in September 1969, Kissinger proposed a plan for what he called a "savage, punishing" blow against North Vietnam code-named Duck Hook to Nixon, arguing that this was the best way to force North Vietnam to agree to peace on American terms.[35] Laird was strongly opposed to Duck Hook, warning Nixon that the use of nuclear weapons to kill a massive number of North Vietnamese civilians would alienate American public opinion from the administration and persuaded Nixon to reject it.[35] Reflecting his background as a Harvard professor of political science who belonged to the Primat der Aussenpolitik school which saw foreign policy as belonging only to a small elite, Kissinger was less sensitive to public opinion than Laird, a former Republican congressman who constantly advised Nixon to keep American public opinion in mind.[35]

Kissinger played a key role in bombing Cambodia to disrupt PAVN and Viet Cong units launching raids into South Vietnam from within Cambodia's borders and resupplying their forces by using the Ho Chi Minh trail and other routes, as well as the 1970 Cambodian Incursion and subsequent widespread bombing of Khmer Rouge targets in Cambodia. The Paris peace talks had become stalemated by late 1969 owing to the obstructionism of the South Vietnamese delegation who wanted the talks to fail.[79] The South Vietnamese President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu did not want the United States to withdraw from Vietnam, and out of frustration with him, Kissinger decided to begin secret peace talks in Paris parallel to the official talks that the South Vietnamese were unaware of.[80] On 21 February 1970, Kissinger secretly met in a modest house in a Paris suburb Lê Đức Thọ, the North Vietnamese diplomat who was to become his most tenacious adversary.[80] In 1981, Kissinger told the journalist Stanley Karnow: "I don't look back on our meetings with any great joy, yet he was a person of substance and discipline who defended the position he represented with dedication".[80] Not until February 1971 were Rogers and Laird first informed of the parallel peace talks in Paris.[80] Kissinger was to meet Tho three times between February-April 1970, and the North Vietnamese first sensed a softening of the American position during these talks as Kissinger slightly altered the "mutual withdrawal formula" that the Americans had previously held to.[81] Nixon was gravely disappointed that the secret talks in Paris did not have the prompt results he wanted.[82] Kissinger wrote in his memoirs that "historians rarely do justice to the psychological stress on a policy-maker", noting that by early 1970 Nixon was feeling very much besieged and inclined to lash out against a world he was believed was plotting his downfall.[83] Nixon had become obsessed with the film Patton, seeing how the film presented Patton as a solitary and misunderstood genius whom the world did not appreciate a parallel to himself and kept watching the film over and over again.[82]

On 18 March 1970, the Prime Minister of Cambodia, Lon Nol carried out a coup against King Sihanouk and ultimately declared Cambodia a republic.[84] Out of fury with Lon Nol, the king went to Beijing where he allied himself to his former enemies, the Khmer Rouge, calling upon the Khmer people to "liberate our motherland".[83] As the most of the Khmer peasantry regarded the king as a god-like figure, the royal endorsement of the Khmer Rouge had immediate results. Cambodia had descended into chaos by late March 1970 as Lon Nol regime to prove its nationalist credibility organized pogroms against the Vietnamese minority, leading the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong to attack and defeat Cambodia's weak army.[83] Nixon believed in the situation in Cambodia offered the chance for him to be like Patton by doing something bold and risky.[85] Kissinger was initially ambivalent about Nixon's plans to invade Cambodia, but as he saw the president was committed, he became more and more supportive.[86] On 23 April 1970, Nixon in a memo to Kissinger declared "we need a bold move in Cambodia to show that we stand with Lon Nol".[86]

On 26 April 1970, Nixon decided to "go for broke" by invading Cambodia with U.S troops.[86] When Nixon's speech-writer William Safire pointed out that the use of U.S. troops violated the Nixon Doctrine that America's Asian allies should do the fighting, Kissinger snapped at him: "We wrote the goddamn doctrine, we can change it!"[87] Kissinger was under immense strain as several of his aides were planning to resign to protest the invasion of Cambodia, his liberal friends from Harvard were pressuring him to resign as well while Nixon was all for more belligerence.[87] Kissinger received a phone call from Nixon and his best friend, Charles "Bebe" Rebozo, who both sounded very drunk; Nixon began the call and then handed the phone to Rebozo who said: "The President wants you to know if this doesn't work, Henry, it's your ass".[87] On 30 April 1970, the United States invaded Cambodia which Nixon announced in a television address that Kissinger contemptuously called "vintage Nixon" because of his overblown rhetoric.[87] At the time, Nixon was seen as recklessly escalating the war and in early May 1970 the largest protests ever against the Vietnam war took place.[88] Four of Kissinger's aides resigned in protest while the Cambodian "incursion" ended several of Kissinger's friendships with colleagues from Harvard when he chose not to resign.[88] Nixon in his memoirs claimed that Kissinger "took a particularly hard line" with regards to the "Cambodian incursion".[88] Roger Morris, one of Kissinger's aides later recalled that he was frightened by the huge anti-war demonstrations, comparing the antiwar movement to Nazis.[88] Kissinger was haunted by memories of his youth in Germany, and had a deep distrust of mass movements of either the left or the right, favoring the Primat der Aussenpolitik school of foreign-policy making by an elite with the masses excluded. In his interview with Karnow, Kissinger maintained he felt torn about where he stood and blamed Nixon for his failure to find "the language of respect and compassion that might have created a bridge at least to the more reasonable elements of the antiwar movement".[88]

The Cambodian "incursion" saw American and South Vietnamese take the areas of eastern Cambodia that American commanders called the Fish Hook and Parrot's Beak and captured an impressive haul of arms originating from China and the Soviet Union.[89] But the majority of Vietnamese Communist forces had withdrawn deeper into Cambodia before the invasion with only a small number left behind to wage a fighting retreat to avoid charges of cowardice.[89] In June 1970, the Americans pulled out of Cambodia and the Vietnamese Communists returned, through the loss of weapons greatly hindered their operations in the Saigon area for the rest of 1970.[90] Having committed itself to supporting Lon Nol, the United States now had two allies instead of one to support in Southeast Asia.[91]

The bombing campaign in Cambodia contributed to the chaos of the Cambodian Civil War, which saw the forces of leader Lon Nol unable to retain foreign support to combat the growing Khmer Rouge insurgency that would overthrow him in 1975.[92][93] Documents uncovered from the Soviet archives after 1991 reveal that the North Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in 1970 was launched at the explicit request of the Khmer Rouge and negotiated by Pol Pot's then second in command, Nuon Chea.[94] The American bombing of Cambodia resulted in 40,000[95]–150,000[96] deaths from 1969 to 1973, including at least 5,000 civilians.[97] Pol Pot biographer David P. Chandler argues that the bombing "had the effect the Americans wanted—it broke the Communist encirclement of Phnom Penh."[98] However, Ben Kiernan and Taylor Owen suggest that "the bombs drove ordinary Cambodians into the arms of the Khmer Rouge, a group that seemed initially to have slim prospects of revolutionary success."[99] Kissinger himself defers to others on the subject of casualty estimates. "...since I am in no position to make an accurate estimate of my own, I consulted the OSD Historian, who gave me an estimate of 50,000 based on the tonnage of bombs delivered over the period of four and a half years."[100][101]

The Cambodian invasion further polarized an already deeply divided nation and the President's Commission on Campus Unrest headed by William Scranton in its report of September 1970 wrote the divisions in American society were "as deep as any since the Civil War".[102] A number of Republican politicians complained to Nixon that his stance on Vietnam was hurting their chances for congressional elections in November 1970, leading the president to say to Kissinger it was natural that liberals like Senator George McGovern and Senator Mark Hatfield wanted to "bug out...But when the Right starts wanting to get out, for whatever reason, that's our problem".[102] In an attempt to change Nixon's image, Kissinger and Nixon devised the notion of a "standstill cease-fire" where both sides would occupy whatever areas of South Vietnam they were holding at the time of the ceasefire, an offer that Nixon publicly made in a television address on 7 October 1970.[103] In his speech, Nixon apparently moved way from the "mutual withdrawal formula" the North Vietnamese kept rejecting by not mentioning it, winning much acclaim, even from his opponents like McGovern and Hatfield (through he also said the withdraw of U.S. forces would be "based on principles" he had "previously" discussed, i.e. the "mutual withdrawal formula").[104] Kissinger and Nixon both disliked the idea of a "standstill ceasefire" as weakening South Vietnam, but fearing if Nixon continued on his present course, he would not be reelected in 1972, the offer was seen as worth the risk, especially since the North Vietnamese rejected it.[105] In private, Kissinger called the "standstill ceasefire" offer as the means that "at a minimum...would give us from temporary relief from public pressures".[106] Subsequently, Kissinger has maintained Nixon's offer of 7 October was sincere and the North Vietnamese made a major error in rejecting it.[106]

In late 1970, Nixon and Kissinger became concerned that the North Vietnamese would launch a major offensive in 1972 to coincide with presidential election, making it imperative to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail in 1971 to prevent the Communists from building up their forces.[107] As the Cooper–Church Amendment had forbidden U.S. troops from fighting in Laos, the plans that was conceived called for South Vietnamese troops with American air support to invade Laos to sever the Ho Chi Minh Trail in operation code-named Lam Son 719.[107] Kissinger wrote about Lam Son "the operation, conceived in doubt and assailed by skepticism, proceeded in confusion".[107] In the first major test of Vietnamization, the ARVN failed miserably. The ARVN invaded Laos on 8 February 1971 and were stopped decisively by the North Vietnamese.[108] In March, Kissinger sent his deputy Haig to inspect the situation personally, leading him to report that the ARVN officers lacked courage and did not want to fight, making retreat the only option.[109] The retreat when it began turned into a rout.[109] Kissinger wrote Lam Son had fallen "far short of our expectations", which he blamed on bad American planning, poor South Vietnamese tactics and Nixon's leadership style, leading Karnow to write he blamed "everyone, characteristically, except himself".[110]

In late May 1971, Kissinger returned to Paris to fruitlessly meet again with Tho.[111] The North Vietnamese demand that Thiệu step down proved to the main obstacle.[111] Kissinger did not want a repeat of the prolonged bout of political instability that characterized South Vietnam from 1963 to 1967 and believed Thiệu was a force for order.[111] Tho suggested to Kissinger that Americans "stop supporting" Thiệu who was running for the reelection in a ballot scheduled for 3 October 1971.[111] Tho claimed that Thiệu's opponents, Air Marshal Nguyễn Cao Kỳ and General Dương Văn Minh aka "Big Minh", were both open to a coalition government with the Viet Cong and had if either men were elected president, the war would be over by late 1971.[111] Thiệu used a legal technicality to disqualify Kỳ while Minh dropped out when it was clear the election was rigged.[111] In the 1971 election, the CIA donated money for Thiệu's reelection campaign while the Americans did not pressure Thiệu to stop rigging the election.[112] Through Kissinger did not regard South Vietnam as important in its own right, he believed it was necessary to support South Vietnam to maintain the United States as a global power, believing that none of America's allies would trust the United States if South Vietnam were abandoned too quickly.[111] Kissinger also believed that if South Vietnam were to collapse, it "leave deep scars on our society, feeling impulses for recrimination".[111] As a Jew who had grown up in Nazi Germany, Kissinger was haunted by how the Dolchstoßlegende had used by the German right to delegitimatize the Weimar Republic, and believed that something similar would happen in the United States should it lose the Vietnam War, fueling the rise of right-wing extremism.[111]

In June 1971, Kissinger supported Nixon's effort to ban the Pentagon Papers saying the "hemorrhage of state secrets" to the media was making diplomacy impossible.[113] Daniel Ellsberg, the man who leaked the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times had been consulted by Kissinger for ideas about Vietnam in late 1968-early 1969, but when he leaked the papers, Kissinger told Nixon that he was a left-wing "fanatic" and a "drug abuser".[113] Kissinger depicted Ellsberg to Nixon as a drug-crazed degenerate of questionable mental stability out to ruin his administration. Reflecting his increasingly frustration with the war, Nixon often talked to Kissinger in a bloodthirsty manner about a "fantasy holocaust" in which he would have U.S. forces kill every living thing in North Vietnam and then pull out, leading the latter appalled by his own account.[111]

By early 1972, Nixon boosted that he had pulled out 400, 000 U.S soldiers from Vietnam since July 1969, and battle deaths had fallen from an average of 200 per week in 1969 down to an average of 10 per week in 1972.[112] The policy of Vietnamization had, as Laird predicted it would, tamed the antiwar movement as most Americans objected not to war in Vietnam per se, only to Americans dying in it.[112] With the antiwar movement in decline by 1972, Nixon believed his chances of reelection were good, but Kissinger kept complaining that he was losing "negotiating assets" in his talks with Tho every time a withdrawal of American forces was announced.[112] Likewise, Kissinger noted that the major reason why Congress despite the antiwar feelings of many of its members kept voting to fund the war was because the argument it was patriotic to support "our boys in the field"; as more Americans were pulled out, Congress was less inclined to vote to fund keeping South Vietnamese "boys in the field".[112] However, the imperatives of being re-elected was far more important to Nixon than with giving Kissinger "negotiating assets".[112] In early 1972, Nixon publicly revealed that Kissinger had secretly negotiating with Tho since 1970 to prove that he was really was committed to peace in Vietnam despite what the antiwar movement had been saying about him for the last three years.[112] Reflecting Kissinger's weakening hand in his talks with Tho, Nixon had increasingly come by 1971–72 to believe that "linkage" concept of improving relations with the Soviet Union and China in exchange for those nations cutting off the supply of weapons to North Vietnam offered his best chance of a favorable peace deal.[112]

On 21 February 1972 was in Nixon's words "the week that changed the world" as he landed in Beijing to meet Mao Zedong.[114] Kissinger who accompanied Nixon to China spent much time talking to the suave Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai about Vietnam, pressing him to end the supply of arms to North Vietnam.[114] The talks went nowhere as Zhou told Kissinger that the North Vietnamese played off China against the Soviet Union, and to cut off North Vietnam would allow it to fall into the Soviet sphere of influence.[114] As the Chinese People's Liberation Army had badly bloodied by the Red Army in a border war in 1969, Zhou stated that to face a two-front war with Chinese forces facing North Vietnam in the south and the Soviet Union in the north was not acceptable to his government.[114] Zhou offered Kissinger only the vague message that China supported efforts to find peace in Vietnam while refusing to make any promises, though Kissinger also noted that Zhou declined to endorse North Vietnam's demands.[114] Despite Nixon's coming visit, in late 1971 the Chinese drastically increased their military aid to North Vietnam and continued to send a massive amount of weapons south even as Nixon and Kissinger exchanged pleasantries with Mao and Zhou in Beijing.[115] As usual, when the Chinese increased their supply of arms to North Vietnam, the Soviet Union did likewise as both Communist states competed with one another for influence in Hanoi by tying to be the biggest supplier of weapons.[115] On 30 March 1972, the PAVN launched the Easter Offensive that overran several provinces in South Vietnam while pushing the ARVN to the brink of collapse.[116]

At the time of the Easter Offensive, Kissinger was deeply involved in planning for Nixon's visit to Moscow in May 1972. The offensive brought to the fore the differences between Nixon and Kissinger. Nixon threatened to cancel his summit with Leonid Brezhnev in Moscow if the Soviet Union did not force North Vietnam to end the Easter Offensive at once, saying: "Whatever else happens, we cannot lose this war. The summit isn't worth a damn if the price for it is losing in Vietnam".[117] Nixon in his instructions to Kissinger stated that he viewed the relations with the Soviet Union through the prism of the Vietnam war and if the Soviets were not prepared to help, Kissinger "should just pack up and come home"..[117] Kissinger for his part believed that Nixon was massively exaggerating Soviet influence in North Vietnam and not longer believed if he ever did in Nixon's "linkage" concept.[117] Kissinger feared that Nixon was obsessed with Vietnam and damaging relations with the Soviet Union over Vietnam would destabilize the international power balance by increasing American-Soviet tensions.[117] On 20 April 1972, Kissinger arrived in Moscow without informing the U.S. ambassador Jacob D. Beam, and then went to have tea with Brezhnev in the Kremlin.[117] Nixon as usual when under stress departed for a marathon drinking session with Rebozo at Camp David, and via Haig kept sending messages to Kissinger to be tough with Brezhnev.[117] As no American president had ever visited Moscow before, Kissinger got the impression that Brezhnev wanted the planned summit to happen "at almost any cost".[117] Kissinger's implemented Nixon's emphasis on building an amicable personal relationship with Brezhnev.[118] Upon his return to Washington, Kissinger reported that Brezhnev would not cancel the summit and was keen to sign the SALT I Treaty.[119] Kissinger went to Paris on 3 May to meet Tho with orders from Nixon that North Vietnam must "Settle or else!"[119] Nixon complained that Kissinger was "obsessed" with the need for a peace treaty while he charged that he now wished he followed his instincts to bomb North Vietnam in 1970, saying if he had done so, the war would have been over by now.[119] On 2 May 1972, the PAVN had captured Quangtri, an important provincial city in South Vietnam, and as a result of this victory, Tho was in no mood for a compromise.[119] Through Kissinger in general shared Nixon's determination to be tough, he was afraid that the president would overreact and destroy the budding détente with the Soviet Union and China by striking too hard at North Vietnam.[119] Moreover, after the rupture caused by the Cambodian incursion, Kissigner was trying hard to rebuilt his relations with the liberal American intelligentsia, saying he did want to become "this administration's Walt Rostow".[119] Kissinger's predecessor, Rostow had once being a professor at Harvard, Oxford the MIT, and Cambridge, but serving as the National Security Adviser had shunned by the Ivy League universities and ended up at the lowly University of Texas, a fate that Kissinger was determined to avoid.[119] On 5 May 1972, Nixon ordered the U.S. Air Force to start bombing Hanoi and Haiphong and on 8 May ordered the U.S Navy to mine the coast of North Vietnam.[119] As the bombings and mining of North Vietnam, Nixon and even more so Kissinger waited anxiously for the Soviet reaction, and much to their relief received only the standard statement decrying the American action and a diplomatic note complaining that American aircraft had bombed a Soviet freighter in Haiphong harbor.[120] The Moscow summit was not canceled.[120]

On 24 July 1972, Congress passed an act calling for the total withdraw of all American forces from Vietnam once all of the American POWs in North Vietnam were released, causing Kissinger to say the North Vietnamese only had to wait until "Congress voted us of the war".[120] However, the sight of Nixon and Kissinger posing for photographs with Brezhnev and Mao deeply worried the North Vietnamese who were afraid of being "sold out" by either China and/or the Soviet Union, causing some flexibility in their negotiating tactics.[120] The Eastern Offensive had not caused the collapse of the South Vietnamese government, but it increased the amount of territory under Communist control.[121] The North Vietnamese were moving towards taking up the "standstill ceasefire" offer and ordered the Viet Cong to seize as much territory as possible in preparation for a "leopard's spot" ceasefire (so called because the patchwork of territories controlled by the Viet Cong and the Saigon government resembled the spots on a leopard's fur).[121] On 1 August 1972, Kissinger met Tho again in Paris, and for first time, he seemed willing to compromise, saying that political and military terms of an armistice could be treated separately and hinted that his government was no longer willing to make the overthrow of Thiệu a precondition.[121]

On the evening of 8 October 1972 at a secret meeting of Kissinger and Tho in a house in the Paris suburb of Gif-sur-Yvette once owned by the painter Fernard Léger came the decisive breakthrough in the talks.[122] Tho believed that Kissinger was as he later it put "in a rush" for a peace deal before the presidential election, and began with he called "a very realistic and very simple proposal" for a ceasefire that would see the Americans pull all their forces out of Vietnam in exchange for the release of all the POWs in North Vietnam.[123] As for the ultimate fate of South Vietnam, Tho proposed the creation of a "council of national reconciliation" that would govern the nation, but in the meantime Thiệu could stay in power until the council was formed while a "leopard's spot" ceasefire would come into effect with the Viet Cong and the Saigon government controlling whatever territories they were had at the time of the ceasefire.[123] The "mutual withdrawal formula" was to be disregarded with PAVN forces to stay in South Vietnam with Tho giving Kissinger a vague promise that no more supplies would be sent down the Ho Chi Minh Trail.[123] Kissinger accepted Tho's offer as the most best deal possible, saying that the "mutual withdrawal formula" had to be abandoned as it been "unobtainable through ten years of war...We could not make it a condition for a final settlement. We had long passed that threshold".[123] Several of Kissinger's own staff, most notably John Negroponte, were strongly opposed to him accepting this offer, saying Kissinger had given away more than he had obtained.[123] In response to Negronponte's objections, Kissinger exploded in rage, accusing him of "nit-picking" and screamed at the top of his voice: "You don't understand. I want to meet their terms. I want to reach an agreement. I want to end this war before the election. It can be done and it will be done...What do you want us to do? Stay there forever?".[123]

Reflecting the "leopard's spot" ceasefire, Kissinger sent Thiệu a message saying he should "seize as much territory as possible" before the ceasefire came into effect while the United States launched Operation Enhance Plus to give South Vietnam as many weapons as possible.[124] Over the course of six weeks in the fall of 1972, South Vietnam ended up with the world's fourth largest air force as the Americans provided as war planes as possibly could.[125] However, neither Kissinger nor Nixon appreciated that for Thiệu any sort of peace deal calling for withdrawal of American forces was unacceptable and he saw the draft peace agreement that Kissinger signed in Paris on 18 October 1972 as a betrayal.[126] On 21 October Kissinger together with the American ambassador Ellsworth Bunker arrived at the Gia Long Palace in Saigon to show Thiệu the peace agreement.[126] The meeting went extremely badly with Thiệu engaged that Kissinger did not take the time to translate the draft peace treaty into Vietnamese, bringing with him only an English language copy.[126] The meeting went from bad to worse with Thiệu having a meltdown as he broke down in tears and hysterically accused Kissinger of plotting with the Soviet Union and China to betray him, saying he could never accept this peace agreement.[126] Thiệu refused to sign the peace agreement and demanded very extensive amendments that Kissinger reported to Nixon "verge on insanity".[126] Nixon ordered Kissinger to "push Thiệu as far as possible", but Thiệu refused to sign the peace agreement.[126] As Kissinger returned to Washington, one of his aides recalled "In twenty-four hours, the bottom fell out".[123]

Through Nixon had initially supported Kissinger against Thiệu, but two of his most influential advisers, namely his Chief of Staff, H.R. Haldeman and the Domestic Affairs Adviser John Ehrlichman urged him to reconsider, arguing that Kissinger had given away too much and Thiệu's objections had merit.[127] As Thiệu sensed Nixon's changing mood, on 24 October 1972 he called a press conference to denounce the draft agreement as a betrayal and stated the Viet Cong "must be wiped out quickly and mercilessly".[127] On October 26, North Vietnam published the draft agreement and accused the United States of tying to "sabotage" it by backing Thiệu.[127] On the same day, Kissinger who until then had never spoken to the media called a press conference at the White House to say: "We believe peace is at hand. We believe an agreement is within sight".[127] Kissinger later admitted that this statement was a major mistake as it inflated hopes for peace while enraging Nixon who saw it as weakness.[127] Nixon came very close to disavowed Kissinger as he declared the draft peace agreement had "differences that must be resolved".[127] Taking up Thiệu's cause as his own, Nixon wanted 69 amendments to the draft peace agreement included in the final treaty and ordered Kissinger back to Paris to force Tho to accept them.[127] Kissinger regarded Nixons' 69 amendments as "preposterous" as he knew Tho would never accept them.[127] By this point, Kissinger's relations with Nixon were tense while Nixon's "German shepherds" Haldeman and Ehrlichman intrigued against him.[127]

As expected, Tho refused to consider any of the 69 amendments and on 13 December 1972 left Paris for Hanoi after he accused the Americans of negotiating in bad faith.[128] Kissinger by this stage was worked up into a state of fury after Tho walked out of the Paris talks and told Nixon: "They're just a bunch of shits. Tawdry, filthy shits".[128] The National Security Adviser now advised Nixon to bomb North Vietnam to make them "talk seriously".[128] On 14 December 1972, Nixon sent an ultimatum demanding that Tho return to Paris to negotiate seriously" within the 72 hours or else he would bomb North Vietnam without limit.[128] Kissinger told the media that the peace agreement was "99 percent completed" but "we will not be blackmailed into an agreement. We will not be stampeded into an agreement and, if I may say so, we will not be charmed into an agreement until its conditions are right".[128] At the same time, Nixon ordered Admiral Thomas Hinman Moorer, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: "I don't want any more of this crap about the fact that we couldn't hit this target or that one. This is your chance to use military power to win this war, and if you don't, I'll hold you responsible".[128] Following the rejection of Nixon's ultimatum, on 18 December, Operation Linebacker II was launched, the so-called Christmas Bombings that lasted until 29 December 1972.[129] During these 11 days that consisted of the heaviest bombing of the entire war, B-52 bombers flew 3, 000 sorties and dropped 40, 000 tons of bombs on Hanoi and Haiphong.[130]

On 26 December, in a press statement Hanoi indicated a willingness to resume the Paris peace talks provided that the bombing stopped.[130] On 8 January 1973, Kissinger and Tho met again in Paris and the next day reached an agreement, which in main points was essentially the same as the one Nixon had rejected in October with only cosmetic concessions to the Americans.[130] Thiệu once again rejected the peace agreement, only to receive an ultimatum from Nixon: "You must decide now whether you desire to continue our alliance or whether you want me to seek a settlement with the enemy which serves U.S. interests alone".[131] Nixon's threat served its purpose and Thiệu reluctantly accepted the peace agreement.[131] On 27 January 1973, Kissinger and Tho signed a peace agreement in Paris that called for the complete withdrawal of all U.S forces from Vietnam by March in exchange for North Vietnam freeing all the U.S POWs.[131] On 29 March 1973, the withdrawal of the Americans from Vietnam was complete and on 1 April 1973, the last POWs were freed.[132] The peace agreement put into effect the "leopard's spot" ceasefire with the Viet Cong being allowed to rule whatever parts of South Vietnam they held at the time of the ceasefire and all of the North Vietnamese troops in South Vietnam were allowed to stay, putting the Communists in a strong position to eventually take over South Vietnam.[131]

On 15 March 1973, Nixon had implied during a speech that the United States might go back into Vietnam should the Communists violate the ceasefire, and as a result Congress began debating a bill to limit American funding for military operations in Southeast Asia.[133] In April, the CIA estimated the total number of PAVN troops in South Vietnam at 150, 000 (about the same as in 1972) whereas Kissinger accused North Vietnam of moving more troops down the Ho Chi Minh Trail.[134] That month, Kissinger met with Tho in Paris to reaffirm their commitment to the Paris peace agreement and to pressure him to stop the Khmer Rouge from overrunning Cambodia.[134] Tho told Kissinger that the Khmer Rouge's leader, Pol Pot, was a Vietnamphobe and North Vietnam had very limited influence over him.[134] At the same time, Kissinger reported to Nixon that "only a miracle" could save South Vietnam now as Thiệu showed no signs of making the necessary reforms to allow the ARVN to fight.[134] His assessment of Cambodia was even more bleaker as the Lon Nol regime had lost control of much of the countryside by the spring of 1973 and only American air strikes prevented the Khmer Rouge from taking Phnom Penh.[134] On 4 June 1973, the Senate passed a bill that already cleared the House of Representatives to block funding for any American military operations in Indochina and Kissinger spent much of the summer of 1973 lobbying Congress to extent the deadline to 15 August in order to keep bombing Cambodia.[134] The Lon Nol regime was saved in 1973 due to heavy American bombing, but the cutoff in funding ended the possibility of an American return to Southeast Asia.[134]

The PAVN had taken heavy losses in the Easter Offensive, but North Vietnamese were rebuilding their strength for a new offensive.[135] By the spring of 1973, Nixon was caught up in the Watergate scandal and was losing interest in foreign affairs.[133] Thiệu's government was still receiving massive amounts of military aid, and his regime controlled 75% of South Vietnam's territory and 85% of the population at the time of the ceasefire.[134] But Thiệu's unwillingness to crackdown on corruption and end the system under which ARVN officers were promoted for political loyalty instead of military merit were structural weaknesses that spelled long term problems for his regime.[135] South Vietnam's economy's had heavily dependent upon the hundreds of millions brought in by spending by the U.S. military and the withdraw of American forces threw the economy into recession. Even more damaging was the Arab oil shock of 1973–74 which destabilized South Vietnam's economy and by the summer of 1974 90% of the ARVN's soldiers were not receiving enough pay to support themselves and their families.[136]

Along with North Vietnamese Politburo Member Le Duc Tho, Kissinger was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize on December 10, 1973, for their work in negotiating the ceasefires contained in the Paris Peace Accords on "Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam", signed the previous January.[41] According to Irwin Abrams, this prize was the most controversial to date. For the first time in the history of the Peace Prize, two members left the Nobel Committee in protest.[3][137] Tho rejected the award, telling Kissinger that peace had not been restored in South Vietnam.[138] Kissinger wrote to the Nobel Committee that he accepted the award "with humility,"[139][140] and "donated the entire proceeds to the children of American servicemembers killed or missing in action in Indochina."[141] After the Fall of Saigon in 1975, Kissinger attempted to return the award.[141][142]

As the South Vietnamese economy to collapse under the weight of inflation caused by the Arab oil shock and rampant corruption, by the summer of 1974, the U.S. embassy reported that morale in the ARVN had fallen to dangerously low levels and it was uncertain how much more longer South Vietnam would last.[136] Widespread protests against corruption that broke out in the summer of 1974 with the protesters accusing Thiệu and his family of corruption indicated that the South Vietnamese regime had lost popular support.[143] In August 1974, Congress passed a bill limiting American aid to South Vietnam to $700 million annually.[144] By November 1974, fearing the worse for South Vietnam as the ARVN continued to lose, Kissinger during the Vladivostok summit lobbied Brezhnev to end Soviet military aid to North Vietnam.[145] The same month, he also lobbied Mao and Zhou to end Chinese military aid to North Vietnam during a visit to Beijing.[145] On 1 March 1975 the PAVN began an offensive that saw them overrun the Central Highlands and by 25 March Hue had fallen.[146] Thiệu was slow to withdraw his armies and by 30 March when Danang fell, the ARVN's best divisions were lost.[147] With the road to Saigon wide open, it became imperative for the North Vietnamese to take the capital before the monsoons began in May, leading to a rapid march on Saigon.[148] On 15 April 1975, Kissinger testified before the Senate Appropriations Committee, urging Congress to increase the military aid budget to South Vietnam by another $700 million to save the ARVN as the PAVN was rapidly advancing on Saigon, which was refused.[148] Kissinger maintained at the time, and still maintains that if only Congress had approved of his request for another $700 South Vietnam would have been saved.[149] In opposition, Karnow argued that by this point, South Vietnam was so far gone with the morale in the ARVN having collapsed it is very doubtful that anything short of sending in U.S. troops again could have saved South Vietnam.[149] On 17 April 1975, the Lon Nol regime collapsed and the Khmer Rouge took Phnom Penh. On 29 April 1975, Option IV, the largest helicopter evacuation began as 70 Marine helicopters flew 8, 000 people from the American embassy in Saigon to the fleet offshore.[150] On 30 April 1975, Saigon fell to the PAVN and the war in Vietnam finally ended.[151]

Bangladesh War

Nixon supported Pakistan's strongman, General Yahya Khan, in the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. Kissinger sneered at people who "bleed" for "the dying Bengalis" and ignored the first telegram from the United States consul general in East Pakistan, Archer K. Blood, and 20 members of his staff, which informed the US that their allies West Pakistan were undertaking, in Blood's words, "a selective genocide" targeting the Bengali intelligentsia, supporters of independence for East Pakistan, and the Hindu minority.[152] In the second, more famous, Blood Telegram the word genocide was again used to describe the events, and further that with its continuing support for West Pakistan the US government had "evidenced [...] moral bankruptcy".[153] As a direct response to the dissent against US policy Kissinger and Nixon ended Archer Blood's tenure as United States consul general in East Pakistan and put him to work in the State Department's Personnel Office.[154][155] Christopher Clary argues that Nixon and Kissinger were unconsciously biased, leading them to overestimate the likelihood of Pakistani victory against Bengali rebels.[156]

Kissinger was particularly concerned about the expansion of Soviet influence in the Indian Subcontinent as a result of a treaty of friendship recently signed by India and the USSR, and sought to demonstrate to the People's Republic of China (Pakistan's ally and an enemy of both India and the USSR) the value of a tacit alliance with the United States.[157][158][159]

Kissinger had also come under fire for private comments he made to Nixon during the Bangladesh–Pakistan War in which he described Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi as a "bitch" and a "witch". He also said "The Indians are bastards", shortly before the war.[160] Kissinger has since expressed his regret over the comments.[161]

Europe

As National Security Adviser under Nixon, Kissinger pioneered the policy of détente with the Soviet Union, seeking a relaxation in tensions between the two superpowers. As a part of this strategy, he negotiated the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (culminating in the SALT I treaty) and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty with Leonid Brezhnev, General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party. Negotiations about strategic disarmament were originally supposed to start under the Johnson Administration but were postponed in protest upon the invasion by Warsaw Pact troops of Czechoslovakia in August 1968.

Nixon felt his administration had neglected relations with the Western European states in his first term and in September 1972 decided that if he was reelected that 1973 would be the "Year of Europe" as the United States would focus on relations with the states of the European Economic Community (EEC) which had emerged as a serious economic rival by 1970.[162] Applying his favorite "linkage" concept, Nixon intended henceforward economic relations with Europe would not be severed from security relations, and if the EEC states wanted changes in American tariff and monetary policies, the price would be defense spending on their part.[163] Kissinger in particular as part of the "Year of Europe" wanted to "revitalize" NATO, which he called a "decaying" alliance as he believed that there was nothing at present to stop the Red Army from overrunning Western Europe in a conventional forces conflict.[164] The "linkage" concept more applied to the question of security as Kissinger noted that the United States was going to sacrifice NATO for the sake of "citrus fruits".[165]

Israeli policy and Soviet Jewry

According to notes taken by H.R. Haldeman, Nixon "ordered his aides to exclude all Jewish-Americans from policy-making on Israel", including Kissinger.[166] One note quotes Nixon as saying "get K. [Kissinger] out of the play—Haig handle it".[166]

In 1973, Kissinger did not feel that pressing the Soviet Union concerning the plight of Jews being persecuted there was in the interest of U.S. foreign policy. In conversation with Nixon shortly after a meeting with Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir on March 1, 1973, Kissinger stated, "The emigration of Jews from the Soviet Union is not an objective of American foreign policy, and if they put Jews into gas chambers in the Soviet Union, it is not an American concern. Maybe a humanitarian concern."[167] Kissinger argued, however:

That emigration existed at all was due to the actions of "realists" in the White House. Jewish emigration rose from 700 a year in 1969 to near 40,000 in 1972. The total in Nixon's first term was more than 100,000. To maintain this flow by quiet diplomacy, we never used these figures for political purposes. ... The issue became public because of the success of our Middle East policy when Egypt evicted Soviet advisers. To restore its relations with Cairo, the Soviet Union put a tax on Jewish emigration. There was no Jackson–Vanik Amendment until there was a successful emigration effort. Sen. Henry Jackson, for whom I had, and continue to have, high regard, sought to remove the tax with his amendment. We thought the continuation of our previous approach of quiet diplomacy was the wiser course. ... Events proved our judgment correct. Jewish emigration fell to about a third of its previous high.[168]

The Arab-Israeli dispute

In 1970, President Nasser of Egypt died and was succeeded by Anwar Sadat, a man whom even more than Kissinger believed in the diplomacy of surprise, in engaging in sudden moves to upset the diplomatic equilibrium. Sadat's liked to say that his favorite game was backgammon, a game where skill and persistence was rewarded, but was best won by sudden gambles, making an analogy between how he played backgammon and conducted his diplomacy. Under Nasser, Egypt and Saudi Arabia had engaged what was known as the Arab Cold War, but Sadat got along very well with King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, forming an alliance between the most populous Arab state and the most wealthiest Arab state. Kissinger later admitted that he was engrossed with the Paris peace talks to end Vietnam war that he and others in Washington missed the significance of the Egyptian-Saudi alliance. At the same that Sadat moved closer to Saudi Arabia, he also wanted a rapprochement with the United States and to move Egypt away from its alliance with the Soviet Union. In July 1972, Sadat expelled all 16, 000 of the Soviet military personnel in Egypt in a signal that he wanted better relations with the United States. Kissinger was taken completely by surprise by Sadat's move, saying: "Why has he done me this favor? Why didn't he demand all sorts of concessions first?"[169]

Sadat expected as a reward that the United States would respond by pressuring Israel to return the Sinai to Egypt, but after his anti-Soviet move prompted no response from the United States, by November 1972 Sadat moved again closer to the Soviet Union, buying a massive amount of Soviet arms for a war he planned to launch against Israel in 1973. For Sadat, cost was no object as the money to buy Soviet arms came from Saudi Arabia. At the same time, Faisal promised Sadat that if it should come to war, Saudi Arabia would embargo oil to the West. In April 1973, the Saudi Oil Minister Ahmed Zaki Yamani visited Washington to meet Kissinger and told him that King Faisal was becoming more and more unhappy with the United States, saying he wanted America to pressure Israel to return all the lands captured in the Six Day War of 1967. In a later interview, Yamani accused Kissinger of not taking his warning seriously, saying all he did was to ask him not to speak anymore of this threat. Angry at Kissinger, Yamani in an interview with the Washington Post on 19 April 1973 warned that King Faisal was considering an oil embargo.[170] At the time, the general feeling in Washington was the Saudis were bluffing and nothing would come of their threat to impose an oil embargo. The fact that Faisal's ineffectual half brother King Saud had imposed a cripplingly oil embargo on Britain and France during the Suez War of 1956 was not considered an important precedent. The CEOs of four of America's oil companies had after speaking to Faisal arrived in Washington in May 1973 with the warning that Faisal was considerably more tougher, intelligent and ruthless than his half-brother Saud whom he had deposed in 1964, and his threats were serious. Kissinger declined to meet the four CEOs.[171]

In 1970, American oil production peaked and the United States began to import more and more oil as oil imports rose by 52% between 1969–1972. Of American oil imports, by 1972 83% were coming from the Middle East. Throughout the 1960s, the price for a barrel of oil remained at $1.80, meaning that with the effects of inflation considered the price of oil in real terms got progressively lower and lower throughout the decade with Americans paying less for oil in 1969 than they had in 1959. Even after a price for a barrel of oil rose to $2.00 in 1971, adjusted for inflation, people in the Western nations were paying less for oil in 1971 than they had in 1958. The extremely low price of oil served as the basis for the "long summer" of prosperity and mass affluence that began in 1945.[172]

In an assessment done by Kissinger and his staff about the Middle East in the summer of 1973, the repeated statements by Sadat about waging jihad against Israel were dismissed as empty talk while the warnings from King Faisal were likewise regarded as inconsequential.[173] In September 1973, Nixon fired Rogers as Secretary of State and replaced him with Kissinger. Kissinger was later to state he had not given been enough time to know the Middle East as he settled into the State Department's office at Foggy Bottom as Egypt and Syria attacked Israel on 6 October 1973.[173]

Documents show that Kissinger delayed telling President Richard Nixon about the start of the Yom Kippur War in 1973 to keep him from interfering. On October 6, 1973, the Israelis informed Kissinger about the attack at 6 am; Kissinger waited nearly 3 and a half hours before he informed Nixon.[174]

According to Kissinger, in an interview in November 2013, he was notified at 6:30 a.m. (12:30 pm. Israel time) that war was imminent, and his urgent calls to the Soviets and Egyptians were ineffective. He says Golda Meir's decision not to preempt was wise and reasonable, balancing the risk of Israel looking like the aggressor and Israel's actual ability to strike within such a brief span of time.[175] More importantly, Israel had built along the banks of the Suez Canal the Bar Lev Line that was considered to be impregnable. The war began on October 6, 1973, when Egypt and Syria attacked Israel. The Egyptians broke through the gigantic sand banks of the Bar Lev Line through the simple device of water cannons, and within two hours were Egyptians soldiers were in the Sinai for the first time since 1967. Kissinger published lengthy telephone transcripts from this period in the 2002 book Crisis. On October 12, under Nixon's direction, and against Kissinger's initial advice,[176] while Kissinger was on his way to Moscow to discuss conditions for a cease-fire, Nixon sent a message to Brezhnev giving Kissinger full negotiating authority.[175] Kissinger wanted to stall a ceasefire to gain more time for Israel to push across the Suez Canal to the African side, and wanted to be perceived as a mere presidential emissary whom to consult the White House all the time as a stalling tactic.[175]

King Hussein of Jordan believed in making peace with Israel, but knowing that the majority of his subjects were Palestinian refugees felt compelled to send a Jordanian armored brigade to fight with the Syrians in the Golan Heights after receiving Israeli permission.[177] Knowing that King Hussein was a moderate who a voice for peace and fearing that he might be overthrown by his subjects if Jordan did not fight, Meir gave her permission for the king to send his troops to fight against her nation. Kissinger commented: "Only in the Middle East is it conceivable that a belligerent would ask its adversary's approval for engaging in an act of war against it".[177]