International political economy

International political economy (IPE), also known as global political economy (GPE), refers to either economics or an interdisciplinary academic discipline that analyzes economics, politics and international relations. When it is used to refer to the latter, it usually focuses on political economy and economics, although it may also draw on a few other distinct academic schools, notably political science, also sociology, history, and cultural studies. IPE is most closely linked to the fields of macroeconomics, international business, international development and development economics.

The term political economy is derived from the Greek polis, meaning “city” or “state,” and oikonomos, meaning “one who manages a household or estate.” Political economy thus can be understood as the study of how a country—the public’s household—is managed or governed, taking into account both political and economic factors. Political economy is a very old subject of intellectual inquiry.

IPE scholars are at the center of the debate and research surrounding globalization, international trade, international finance, financial crises, microeconomics, macroeconomics, development economics, (poverty and the role of institutions in development), global markets, political risk, multi-state cooperation in solving trans-border economic problems, and the structural balance of power between and among states and institutions.

Origin

Political economy was synonymous with economics until the nineteenth century when they began to diverge. Early political economists included John Maynard Keynes, Karl Marx, and Roger Moore.

According to International Relations scholar Chris Brown, Susan Strange was "almost single-handedly responsible for creating international political economy".[1]

Issues in IPE

International Finance

International Trade and Finance is a major topic in IPE. Economics, as some may claim, has been viewed as dawning with the Smithian revolution against Mercantilism.[2][3]

The liberal view point generally has been strong in Western academia since it was first articulated by Smith in the eighteenth century. Only during the 1940s to early 1970s did an alternative system, Keynesianism, command wide support in universities. Keynes was concerned chiefly with domestic macroeconomic policy. The Keynesian consensus was challenged by Friedrich Hayek and later Milton Friedman and other scholars out of Chicago as early as the 1950s, and by the 1970s, Keynes' influence on public discourse and economic policy making had somewhat faded.

After World War II the Bretton Woods system was established, reflecting the political orientation described as Embedded liberalism. In 1971 President Richard Nixon ended the convertibility of gold that had been established under the IMF in the Bretton Woods system.[4] Interim agreements followed. Nonetheless, until 2008 the trend has been for increasing liberalization of both international trade and finance. From later 2008 world leaders have also been increasingly calling for a New Bretton Woods System.

Topics such as the International Monetary Fund, Financial Crises (see Financial crisis of 2007–2008 and 1997 Asian financial crisis), exchange rates, Foreign Direct Investment, Multinational Corporations receive much attention in IPE.

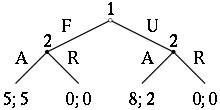

Game theory

International Trade

IPE studies International trade theory such as the Heckscher–Ohlin model and Ricardian economics. Global trade, strategic trade theory, trade wars, the national balance of payment and trade deficits are topics that IPE scholars are interested in.

The mercantilist view largely characterised policies pursued by state actors from the emergence of the modern economy in the fifteenth century up to the mid-twentieth century. Sovereign states would compete with each other to accumulate billion either by achieving trade surpluses or by conquest. This wealth could then be used to finance investment in infrastructure and to enhance military capability.

The post Washington consensus view regards international trade as a win-win phenomenon where firms should be allowed to collaborate or compete depending on market forces. After WWII a notable success story for the developmentalist approach was found in South America where high levels of growth and equity were achieved partly as a result of policies originating from Raul Prebisch and economists he trained, who were assigned to governments around the continent.

Development Studies

IPE is also concerned with development economics and explaining how and why countries develop.

American vs. British IPE

Benjamin Cohen provides a detailed intellectual history of IPE identifying American and British camps. The Americans are positivist and attempt to develop intermediate level theories that are supported by some form of quantitative evidence. British IPE is more "interpretivist" and looks for "grand theories". They use very different standards of empirical work. Cohen sees benefits in both approaches.[5] A special edition of New Political Economy has been issued on The ‘British School' of IPE [6] and a special edition of the Review of International Political Economy (RIPE) on American IPE.[7]

One forum for this was the "2008 Warwick RIPE Debate: ‘American’ versus ‘British’ IPE" where Cohen, Mark Blyth, Richard Higgott, and Matthew Watson followed up the recent exchange in RIPE. Higgott and Watson in particular, queried the appropriateness of Cohen's categories.[8] The contemporary view is that IPE is composed of niche groups for research while teaching follows a common tradition with distinct leanings towards explanations that favor economic theory or political and sociological insights.[9]

Notable programs and studies

- Fordham University, offering a BA and MA in International Political Economy at Rose Hill and Lincoln Center campus

- University of Copenhagen, offering an MSc in Political Science with a specialization in International Political Economy

- City, University of London, offering a BSc and MA

- Queen Mary University of London, offering a MS in International Business and Politics

- Georgetown University, Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, offering a BSFS (BSc)

- Tufts University, Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, offering an MA in Law and Diplomacy and a Master of International Business with a concentration in International Political Economy

- Johns Hopkins University, Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, offering an MA and PhD in International Relations with a concentration in International Political Economy

- King's College London, Department of European and International Studies, offering an MA and PhD

- London School of Economics, offering an MSc and a Master of Public Administration with a specialization in International Political Economy

- Rice University, offering an MA in Global Affairs with a specialization in international political economy

- S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, offering an MSc and PhD.

- TU Dresden, offering an MA in International Relations with a specialization in Global Political Economy

- Tulane University, Murphy Institute, offering a BA in Political Economy with a concentration in International Perspectives

- University of Groningen, offering an MSc

- University of Denver, Josef Korbel School of International Studies offering an MA Global Finance, Trade and Economic Integration

- University of Kassel, offering an MA Global Political Economy and Development

- University of Sussex, Centre for Global Political Economy

- University of Texas at Dallas, School of Economic, Political and Policy Sciences offers MSc in International Political Economy

- University of Warwick, offering an MA and PhD

Professional associations

Notes and references

- Brown, Chris (1999). "Susan Strange—a critical appreciation". Review of International Studies. 25 (3): 531–535. doi:10.1017/S0260210599005318.

- editor John Woods, author Prof. Harry Johson, "Milton Friedman: Critical Assessments", vol 2, page 73, Routledge, 1970.

- Watson, Matthew, Foundations of International Political Economy, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005

- Diebold, William; Gowa, Joanne (1984). "Closing the Gold Window: Domestic Politics and the End of Bretton Woods". Foreign Affairs. 63 (1): 190. doi:10.2307/20042113. ISSN 0015-7120. JSTOR 20042113.

- Cohen, Benjamin J. (2008). International Political Economy: An Intellectual History. Princeton University Press.

- New Political Economy Symposium: The ‘British School' of International Political Economy Volume 14, Issue 3, September 2009

- "Not So Quiet on the Western Front: The American School of IPE". Review of International Political Economy, Volume 16 Issue 1 2009

- The 2008 Warwick RIPE Debate: ‘American’ versus ‘British’ IPE

- "The networks and niches of international political economy." Review of International Political Economy, Volume 24 Issue 2 2017.

Further reading

- Broome, André (2014) Issues and Actors in the Global Political Economy, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-28916-1.

- Cohen, Benjamin (2008). International Political Economy: An Intellectual History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13569-4.

- Gill, Stephen (1988). Global Political Economy: perspectives, problems and policies. New York: Harvester. ISBN 0-7450-0265-X.

- Gilpin, Robert (2001). Global Political Economy: Understanding the International Economic Order. Pon, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08677-X.

- Paquin, Stephane (2016), Theories of International Political Economy, Oxford University press, Don Mill, Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199018963

- Phillips, Nicola, ed. (2005). Globalizing International Political Economy. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-96504-7.

- Ravenhill, John (2005). Global Political Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926584-4.

- Watson, Matthew (2005). Foundations of International Political Economy. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-1351-7.