Gigantoraptor

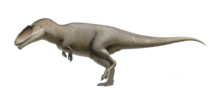

Gigantoraptor (meaning "giant seizer") is a genus of large oviraptorosaurian theropod dinosaur that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous period. It was a giant, ground-dwelling bipedal omnivore with a shearing bite as indicated by the preserved mandible.[1]

| Gigantoraptor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed Gigantoraptor skeleton with Oviraptor (below), in Japan | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Caenagnathidae |

| Genus: | †Gigantoraptor Xu et al., 2007 |

| Species: | †G. erlianensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Gigantoraptor erlianensis Xu et al., 2007 | |

Discovery and naming

In a quarry at Saihangaobi, Iren Dabasu Formation, Erlian basin, Sonid Left Banner (Inner Mongolia), numerous remains of the sauropod Sonidosaurus have been uncovered since 2001. Chinese paleontologist Xu Xing was asked to reenact the discovery of Sonidosaurus in April 2005 for a Japanese documentary. Xu obliged them by digging out a thighbone. As he wiped the bone clean, he suddenly realized it was not from a sauropod, but from an unidentified theropod in the size class of Albertosaurus. He then stopped the filming to secure the serendipitous find. This way, the discovery of the Gigantoraptor holotype fossil was documented on film.[1] That holotype, LH V0011, consists of the incomplete and disassociated remains of a single subadult individual, preserving a nearly complete mandible, a partial isolated cervical vertebra, dorsal vertebrae, caudal vertebrae, right scapula, right humerus, right radius and ulna, nearly complete right manus, partial ilium with a nearly complete pubis and hind limbs, including both femur, tibia and fibula with virtually complete pes.[1]

In 2007, the type species Gigantoraptor erlianensis was named and described by Xu, Tan Qingwei, Wang Jianmin, Zhao Xijin and Tan Lin. The generic name, Gigantoraptor, is derived from the Latin gigas, gigantis, meaning "giant" and raptor, meaning "seizer". The specific name, erlianensis, refers to the Erlian Basin.[1]

Description

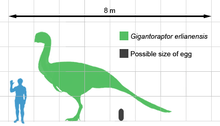

It was clear to Xu et al. that Gigantoraptor belonged to the Oviraptorosauria, a group named after Oviraptor, but compared to other known members, Gigantoraptor was much larger, approximately three times as long and 35 times more massive than the heaviest earlier discovered oviraptorosaurid Citipati. Xu et al. estimated its length at 8 m (26 ft), a height of 5 m (16 ft) and the weight at 1.4 t (1,400 kg), but Xu et al. infer that Gigantoraptor reached its young adult size within seven years and was still at relatively early young adult stage at the time of death, and estimate that a full-sized Gigantoraptor is considerably heavier than 1.4 t (1,400 kg).[1] In 2010, Gregory S. Paul even gave an estimate of 2 t (2,000 kg).[2] However, the paleontologist Thomas Holtz has estimated its size at 8.6 m (28 ft) with a weight between 0.9 to 3.6 t (900.0 to 3,600.0 kg) in 2012.[3]

The preserved mandible of Gigantoraptor is fused into a broad shovel-like shape, indicating that the unknown skull was over half a metre long and toothless also, probably equipped with a horny beak. The anterior caudal vertebrae have very long neural spines and are heavily pneumaticised with deep pleurocoels. The middle section of the relatively short tail is somewhat stiffened by long prezygapophyses. The caudal vertebrae are lightened by spongeous bone. The forelimbs are rather long because of an elongated slender manus. The humerus is bowed outwards to an exceptionally large extent and has a very rounded head. The first metacarpal is very short and carries a strongly diverging thumb. The hindlimbs are relatively elongated, a trait also mentioned by Holtz.[3] The femur is slender with a distinct head and neck, measuring 110 cm (43 in). The pes is robust with large and strongly curved pedal unguals.[1]

Distinguishing characteristics

According to Xu et al. 2007, Gigantoraptor can be recognised by the following traits:[1]

- Reduced mandible with 45% less length compared to the femur.

- Anterior caudal vertebrae with elongated neural spines and posteriorly located stocky, rod-like transverse processes.

- Dentary with elongated postero-ventral process reaching to the level of the glenoid.

- Reduced posteriorly tapered retro articular process much deeper than its wide.

- Anterior and middle caudal vertebrae with a large pneumatic opening on the ventral surface.

- Dentary with two fossa on the lateral surface and close to the external mandibular fenestra.

- Anterior caudal centrum with postero-ventral margin extending ventrally.

- Advanced laminal system of the anterior caudal vertebrae.

- Vertical prezygapophyseal articular facets located proximal to the distal end of the process in the middle caudal vertebrae.

- Scapula with prominent convexity ventral to the acromion process on the lateral surface.

- Reduced calcaneum obscured from anteriorview by the expanded astragalus.

- Distal tarsal IV with proximal projection on the lateral margin.

- Anterior caudal vertebrae composed of opisthocoelous, amphicoelous and procoelous.

- Pleurocoels present on most caudal vertebrae

- Anterior caudal vertebrae centrum with a pair of vertically arranged pneumatic openings on the lateral surface.

- Bowed humerus with a prominent, spherical top and a curved delto-pectoral crest.

- Proximal section of the humerus with a centrally constricted thick ridge running along the posterior margin.

- Sub-circular, concave proximal articular surface present in the straight ulna.

- Metatarsal III with ginglymoid distal end.

- Constricted proximal articular surface and two lateral splines present in the pedal unguals.

- Radius featuring a sub-spherical distal end.

- Convex medial margin of the proximal end and a medial condyle three times elongated and extending further more distally than the lateral one on the distal end of the Metacarpal I.

- Prominent dorso-lateral process on the proximal end and a longitudinal spline on the ventral margin of the proximal third of the end in the Metacarpal II.

- Narrow spline-medial to the trochanteric head extending down to the posterior margin of the femoral end, and a patellar spline present on the anterior surface of the distal end.

- Manual unguals with triangular lateral splines.

- Pubis laterally compressed.

- Femur with straight end.

- Neck tightened between the postero-medially oriented spherical femoral top and the anteroposteriorly expanded trochanteric crest that is more stocky and higher anteriorly than posteriorly.

No direct evidence of feathers was preserved with the skeleton, but Xu et al. discussed their likely presence on Gigantoraptor. They admitted that despite Gigantoraptor being a member of the Oviraptorosauria, a group that includes the feathered species Caudipteryx and Protarchaeopteryx, it might have been "naked" because it is three hundred times as massive as these species, and very large animals may rely more on mass for temperature regulation, losing the insulating coverings found on their smaller relatives. However, they suggested that at least arm feathers were probably still present on Gigantoraptor, since their primary functions, such as display and covering the eggs while brooding, are not related to the regulation of body heat.[1]

Classification

In 2007, Xu et al. assigned Gigantoraptor to the Oviraptoridae, in a basal position. The anatomy of Gigantoraptor includes the diagnostic features of the Oviraptorosaurs. However, it also includes several features found in more derived eumaniraptoran dinosaurs, such as a forelimb/hindlimb ratio of 60%, a lack of expansion of the distal scapula and the lack of a fourth trochanter on the femur. Despite its size, Gigantoraptor would thus have been more bird-like than its smaller oviraptorosaurian relatives.[1]

In 2010, a second analysis of Gigantoraptor relationships found it to be a member of the Caenagnathidae rather than an oviraptorid.[4] Phylogenetic analysis conducted by Lamanna et al. (2014), supported that Gigantoraptor was a basal caenagnathid.[5]

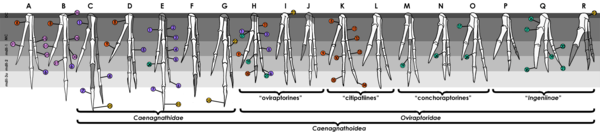

The cladogram below follows the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Funston & Currie in 2016, which found Gigantoraptor to be a Caenagnathid.[6]

| Caenagnathidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

The diet of Gigantoraptor is uncertain. Although some oviraptorosaurs, such as Caudipteryx and Incisivosaurus, are thought to have been mostly herbivorous, because Gigantoraptor has a small head and long neck like many herbivores. Gigantoraptor had long hind legs with proportions that allowed for fast movement (it was probably more nimble than the heavier and less agile Tarbosaurus), and large claws, a combination that is not usually found in herbivores of this size.[1] Paul suggested that Gigantoraptor was also a herbivore and used its speed to escape predators.[2] The preserved jaw for Gigantoraptor also indicates that the theropod had a shearing bite, possibly for cutting through plants (and potentially meat). This is comparable to other caenagnathids and contrasting with the jaws of oviraptorids, whose jaws seem better suited for crushing food.[7]

The specimen has advanced ossification and growth rings in the fibula that indicate it was likely 11 years old when it died. It appears to have reached an early young adult stage at age seven, and probably would have grown much larger when it reached the adult stage. This indicates a growth rate that is faster than in most large non-avian theropods.[1]

The existence of giant oviraptorosaurians, such as Gigantoraptor, explains several earlier Asian finds of very large, up to 53 centimetres long, oviraptorosaurian eggs, assigned to the oospecies Macroelongatoolithus carlylensis. These were laid in enormous rings with a diameter of three metres.[2] The presence of Macroelongatoolithus in North America indicates that gigantic oviraptorosaurs were present there as well, though no fossil skeletal remains have been found.[8]

Paleoecology

Gigantoraptor was unearthed from the Iren Dabasu Formation, with a existence between 95 million to 80 million years ago.[3] During the times of the Late Cretaceous, in this area existed a large braided river valley with floodplain and fluvial environments. These environments had extensive vegetation, evidenced in the palaeosol development and the numerous herbivorous dinosaurs remains that were found in both the river channel and the floodplain sediments.[9] Here, it lived alongside other Theropods: Alectrosaurus, Archaeornithomimus, Avimimus, Caenagnathasia, Erliansaurus, Mononykus, Neimongosaurus, Saurornithoides and Velociraptor; the sauropod Sonidosaurus, and hadrosaurids: Bactrosaurus and Gilmoreosaurus.[10][11][9][12][13]

See also

| Wikispecies has information related to Gigantoraptor |

- Timeline of oviraptorosaur research

- 2007 in paleontology

- Xu Xing

- Iren Dabasu Formation

- Oviraptorosauria

References

- Xing, X.; Tan, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Tan, L. (2007). "A gigantic bird-like dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of China". Nature. 447 (7146): 844–847. doi:10.1038/nature05849. PMID 17565365. Supplementary Information

- Paul, Gregory S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. p. 153.

- Holtz, T. R.; Rey, L. V. (2007). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. Random House. Genus List for Holtz 2012 Weight Information

- Longrich, N. R.; Currie, P. J.; Zhi-Ming, D. (2010). "A new oviraptorid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Bayan Mandahu, Inner Mongolia". Palaeontology. 53 (5): 945–960. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00968.x.

- Lamanna, M. C.; Sues, H. D.; Schachner, E. R.; Lyson, T. R. (2014). "A New Large-Bodied Oviraptorosaurian Theropod Dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Western North America". PLoS ONE. 10 (4): e0125843. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092022.

- Funston, G.; Currie, P. J. (2016). "A new caenagnathid (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, Canada, and a reevaluation of the relationships of Caenagnathidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (4): e1160910. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1160910.

- Ma, W.; Wang, J.; Pittman, M.; Tan, Q.; Tan., L.; Guo, B.; Xu, X. (2017). "Functional anatomy of a giant toothless mandible from a bird-like dinosaur: Gigantoraptor and the evolution of the oviraptorosaurian jaw". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 16247. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-15709-7. PMC 5701234. PMID 29176627.

- Simon, D. J. (2014). "Giant Dinosaur (Theropod) eggs of the Oogenus Macroelongatoolithus (Elongaroolithidae) from Southeastern Idaho: Taxonimic, Paleobiogeographic, and Reproductive implications" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Van Itterbeeck, J.; Horne, D. J.; Bultynck, P.; Vandenberghe, N. (2005). "Stratigraphy and palaeoenvironment of the dinosaur-bearing Upper Cretaceous Iren Dabasu Formation, Inner Mongolia, People's Republic of China". Cretaceous Research. 26 (4): 699–725. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2005.03.004.

- Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmolska, H. (2007). "Dinosaur Distribution". The Dinosauria, Second Edition. University of California Press. p. 598.

- Xi, Y.; Xiao-Li, W.; Sullivan, C.; Shuo, W.; Stidham, T.; Xing, X. (2015). "Caenagnathasia sp. (Theropoda: Oviraptorosauria) from the Iren Dabasu Formation (Upper Cretaceous: Campanian) of Erenhot, Nei Mongol, China" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 53 (4): 291 298.

- Xing, X.; Xiaohong, Z.; Qingei, T.; Xijin, Z.; Lin, T. (2006). "A New Titanosaurian Sauropod from Late Cretaceous of Nei Mongol, China" (PDF). Acta Geologica Sinica. 80 (1): 20–26. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2006.tb00790.x.

- Averianov, A.; Sues, H. (2012). "Correlation of Late Cretaceous continental vertebrate assemblages in Middle and Central Asia" (PDF). Journal of Stratigraphy. 36 (2): 462–485.

External links

- news@nature.com: "Giant bird-like dinosaur found".

- Wired Science Scientists Discover 3,000-Pound Gigantoraptor Dinosaur in Mongolia

- Fleshed-out restoration of a Gigantoraptor erlianensis. Credit: Julius T. Csotonyi

- Yahoo! News: China finds new species of big, bird-like dinosaur

- Description: Factsheet with picture English/German at Dinosaurier-Web

.jpg)

.png)