Carnotaurus

Carnotaurus /ˌkɑːrnoʊˈtɔːrəs/ is a genus of large theropod dinosaur that lived in South America during the Late Cretaceous period, between about 72 and 69.9 million years ago. The only species is Carnotaurus sastrei. Known from a single well-preserved skeleton, it is one of the best-understood theropods from the Southern Hemisphere. The skeleton, found in 1984, was uncovered in the Chubut Province of Argentina from rocks of the La Colonia Formation. Carnotaurus is a derived member of the Abelisauridae, a group of large theropods that occupied the large predatorial niche in the southern landmasses of Gondwana during the late Cretaceous. The phylogenetic relations of Carnotaurus are uncertain; it might have been closer to either Majungasaurus or Aucasaurus.

| Carnotaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeletal cast at Chlupáč Museum in Prague | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Abelisauridae |

| Clade: | †Furileusauria |

| Tribe: | †Carnotaurini |

| Genus: | †Carnotaurus Bonaparte, 1985 |

| Species: | †C. sastrei |

| Binomial name | |

| †Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte, 1985 | |

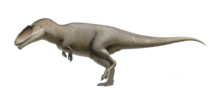

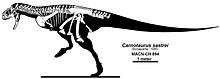

Carnotaurus was a lightly built, bipedal predator, measuring 7.5 to 9 m (24.6 to 29.5 ft) in length and weighing at least 1.35 metric tons (1.33 long tons; 1.49 short tons). As a theropod, Carnotaurus was highly specialized and distinctive. It had thick horns above the eyes, a feature unseen in all other carnivorous dinosaurs, and a very deep skull sitting on a muscular neck. Carnotaurus was further characterized by small, vestigial forelimbs and long, slender hindlimbs. The skeleton is preserved with extensive skin impressions, showing a mosaic of small, non-overlapping scales approximately 5 mm in diameter. The mosaic was interrupted by large bumps that lined the sides of the animal, and there are no hints of feathers.

The distinctive horns and the muscular neck may have been used in fighting conspecifics. According to separate studies, rivaling individuals may have combated each other with quick head blows, by slow pushes with the upper sides of their skulls, or by ramming each other head-on, using their horns as shock absorbers. The feeding habits of Carnotaurus remain unclear: some studies suggest the animal was able to hunt down very large prey such as sauropods, while other studies find it preyed mainly on relatively small animals. Carnotaurus was well adapted for running and was possibly one of the fastest large theropods.

Description

Carnotaurus was a large but lightly built predator.[1] The only known individual was about 7.5–9 m (24.6–29.5 ft) in length,[upper-alpha 1][upper-alpha 2][4] making Carnotaurus one of the largest abelisaurids.[upper-alpha 3][upper-alpha 4][4] While Ekrixinatosaurus and possibly Abelisaurus, highly incomplete, would have been similar or larger in size,[upper-alpha 5][upper-alpha 6][upper-alpha 7] a 2016 study found that only Pycnonemosaurus, at 8.9 m (29.2 ft), was longer than Carnotaurus, which was estimated at 7.8 m (25.6 ft).[7] Its mass is estimated to have been 1,350 kg (1.33 long tons; 1.49 short tons)[upper-alpha 8] 1,500 kg (1.5 long tons; 1.7 short tons)[upper-alpha 9] 2,000 kg (2.0 long tons; 2.2 short tons)[4] and 2,100 kg (2.1 long tons; 2.3 short tons)[upper-alpha 10] in separate studies that used different estimation methods. Carnotaurus was a highly specialized theropod, as seen especially in characteristics of the skull, the vertebrae and the forelimbs.[upper-alpha 11] The pelvis and hindlimbs, on the other hand, remained relatively conservative, resembling those of the more basal Ceratosaurus. Both the pelvis and hindlimb bones were long and slender. The left thigh bone of the individual measures 103 cm in length, but shows an average diameter of only 11 cm.[upper-alpha 12]

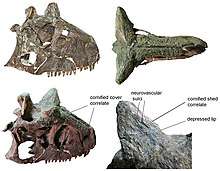

Skull

The skull, measuring 59.6 cm (23.5 in) in length, was proportionally shorter and deeper than in any other large carnivorous dinosaur.[upper-alpha 13][upper-alpha 14] The snout was moderately broad, not as tapering as seen in more basal theropods like Ceratosaurus, and the jaws were curved upwards.[11] As in other abelisaurids, the facial bones, especially the nasal bones, were sculptured with numerous small holes and spikes.[upper-alpha 15] In life, a wrinkled and possibly keratinous skin would have covered these bones.[upper-alpha 16] A prominent pair of horns protruded obliquely above the eyes. These horns, formed by the frontal bones,[upper-alpha 17] were thick and cone-shaped, but somewhat vertically flattened in cross-section, and measured 15 cm (5.9 in) in length.[12] In life, they would probably have formed the bony cores of much longer keratinous horns.[upper-alpha 18] The proportionally small eyes[13] were situated in the upper part of the keyhole shaped orbita (eye sockets).[upper-alpha 19] The upper part was slightly rotated forward, probably permitting some degree of binocular vision.[upper-alpha 20]

The teeth were long and slender,[13] as opposed to the usually very short teeth seen in other abelisaurids.[11] On each side of the upper jaws there were four premaxillary and twelve maxillary teeth,[upper-alpha 21] while the lower jaws were equipped with fifteen dentary teeth per side.[upper-alpha 22] In contrast to the robust-looking skull, the lower jaw was shallow and weakly constructed, with the dentary (the foremost jaw bone) connected to the hindmost jaw bones by only two contact points.[13][upper-alpha 23] The lower jaw was found with hyoid bones, in the position they would be in if the animal was alive. These slender bones, supporting the tongue musculature and several other muscles, are rarely found in dinosaurs because they are not connected to other bones and therefore get lost easily.[upper-alpha 24][14]

Vertebrae

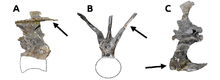

The vertebral column consisted of ten cervical (neck), twelve dorsal, six fused sacral[upper-alpha 25] and an unknown number of caudal (tail) vertebrae.[2] The neck was nearly straight, rather than having the S-curve seen in other theropods, and also unusually wide, especially towards its base.[15] The top of the neck's spinal column featured a double row of enlarged, upwardly directed bony processes called epipophyses, creating a smooth trough on the top of the neck vertebrae. These processes were the highest points of the spine, towering above the unusually low spinous processes.[2][14] The epipophyses probably provided attachment areas for a markedly strong neck musculature.[upper-alpha 26] A similar double row was also present in the tail, formed there by highly modified caudal ribs, in front view protruding upwards in a V-shape, their inner sides creating a smooth, flat, top surface of the front tail vertebrae. The end of each caudal rib was furnished with a forward projecting hook-shaped expansion that connected to the caudal rib of the preceding vertebra.[14][16]

Forelimbs

The forelimbs were proportionally shorter than in any other large carnivorous dinosaurs, including Tyrannosaurus.[upper-alpha 27] The forearm was only a quarter the size of the upper arm. There were no carpalia in the hand, so that the metacarpals articulated directly with the forearm.[17] The hand showed four basic digits,[2] though apparently only the middle two of these ended in finger bones, while the fourth consisted of a single splint-like metacarpal that may have represented an external 'spur'. The fingers themselves were fused and immobile, and may have lacked claws.[18] Carnotaurus differed from all other abelisaurids in having proportionally shorter and more robust forelimbs, and in having the fourth, splint-like metacarpal as the longest bone in the hand.[17] A 2009 study suggests that the arms were vestigial in abelisaurids, because nerve fibers responsible for stimulus transmission were reduced to an extent seen in today's emus and kiwis, which also have vestigial forelimbs.[19]

Skin

Carnotaurus was the first theropod dinosaur discovered with a significant number of fossil skin impressions.[20] These impressions, found beneath the skeleton's right side, come from different body parts, including the lower jaw,[20] the front of the neck, the shoulder girdle, and the rib cage.[upper-alpha 28] The largest patch of skin corresponds to the anterior part of the tail.[upper-alpha 29] Originally, the right side of the skull also was covered with large patches of skin—this was not recognized when the skull was prepared, and these patches were accidentally destroyed. Still, the surface texture of much of the right side of the skull is very different from that of the left side, and probably shows some features of the scalation pattern of the head.[20]

The skin was built up of a mosaic of polygonal, non-overlapping scales measuring approximately 5 mm (0.20 in) in diameter. This mosaic was divided by thin, parallel grooves.[upper-alpha 30] Scalation was similar across different body parts with the exception of the head, which apparently showed a different, irregular pattern of scales.[upper-alpha 31][21] There is no evidence of feathers.[20] Uniquely for theropods, there were osteoderms (knob-like skin bones) running along the sides of the neck, back and tail in irregular rows. Each bump showed a low ridge and measured 4 to 5 cm (1.6 to 2.0 in) in diameter. They were set 8 to 10 cm (3.1 to 3.9 in) apart from each other and became larger towards the animal's top. The bumps probably represent clusters of condensed scutes, similar to those seen on the soft frill running along the body midline in hadrosaurid ("duck-billed") dinosaurs.[upper-alpha 32][20] Stephen Czerkas (1997) suggested that these structures may have protected the animal's sides while fighting members of the same species (conspecifics) and other theropods, arguing that similar structures can be found on the neck of the modern iguana where they provide limited protection in combat.[20]

Classification

Carnotaurus is one of the best-understood genera of the Abelisauridae, a family of large theropods restricted to the ancient southern supercontinent Gondwana. Abelisaurids were the dominant predators in the Late Cretaceous of Gondwana, replacing the carcharodontosaurids and occupying the ecological niche filled by the tyrannosaurids in the northern continents.[1] Several notable traits that evolved within this family, including shortening of the skull and arms as well as peculiarities in the cervical and caudal vertebrae, were more pronounced in Carnotaurus than in any other abelisaurid.[upper-alpha 33][upper-alpha 34][16]

Though relationships within the Abelisauridae are debated, Carnotaurus is consistently shown to be one of the most derived members of the family by cladistical analyses.[upper-alpha 35] Its nearest relative might have been either Aucasaurus[22][23][24] or Majungasaurus;[25][26][27] this ambiguity is largely due to the incompleteness of the Aucasaurus skull material.[upper-alpha 36][upper-alpha 37] A recent review suggests that Carnotaurus was not closely related to either Aucasaurus or Majungasaurus, and instead proposed Ilokelesia as its sister taxon.[upper-alpha 38]

Carnotaurus is eponymous for two subgroups of the Abelisauridae: the Carnotaurinae and the Carnotaurini. Paleontologists do not universally accept these groups. The Carnotaurinae was defined to include all derived abelisaurids with the exclusion of Abelisaurus, which is considered a basal member in most studies.[28] However, a 2008 review suggested that Abelisaurus was a derived abelisaurid instead.[upper-alpha 39] Carnotaurini was proposed to name the clade formed by Carnotaurus and Aucasaurus;[23] only those paleontologists who consider Aucasaurus as the nearest relative of Carnotaurus use this group.[29]

Below is a cladogram published by Canale and colleagues in 2009.[22]

| Carnotaurinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Discovery

The only skeleton (holotype MACN-CH 894) was unearthed in 1984 by an expedition led by Argentinian paleontologist José Bonaparte.[upper-alpha 40] This expedition also recovered the peculiar spiny sauropod Amargasaurus.[30] It was the eighth expedition within the project named "Jurassic and Cretaceous Terrestrial Vertebrates of South America", which started in 1976 and was sponsored by the National Geographic Society.[30][upper-alpha 41] The skeleton is well-preserved and articulated (still connected together), with only the posterior two thirds of the tail, much of the lower leg, and the hind feet being destroyed by weathering.[upper-alpha 42][31] During fossilization, the skull and especially the muzzle were crushed laterally, while the premaxilla were pushed upwards onto the nasal bones. As a result, the upward curvature of the upper jaw is artificially exaggerated in the holotype.[upper-alpha 43] The skeleton belonged to an adult individual, as indicated by the fused sutures in the braincase.[12] It was found lying on its right side, showing a typical death pose with the neck bent back over the torso.[20] Unusually, it is preserved with extensive skin impressions.[upper-alpha 44] In view of the significance of these impressions, a second expedition was started to reinvestigate the original excavation site, leading to the recovery of several additional skin patches.[20]

The skeleton was collected on a farm named "Pocho Sastre" near Bajada Moreno in the Telsen Department of Chubut Province, Argentina.[31] Because it was embedded in a large hematite concretion, a very hard kind of rock, preparation was complicated and progressed slowly.[13][31] In 1985, Bonaparte published a note presenting Carnotaurus sastrei as a new genus and species and briefly describing the skull and lower jaw.[31] The generic name Carnotaurus means "meat-eating bull", an allusion to the animal's bull-like horns.[32] The specific name sastrei honors Angel Sastre, the owner of the ranch where the skeleton was found.[33] A comprehensive description of the whole skeleton followed in 1990.[2] After Abelisaurus, Carnotaurus was the second member of the family Abelisauridae that was discovered.[34] For years, it was by far the best-understood member of its family, and also the best-understood theropod from the Southern Hemisphere.[35][36] It was not until the 21st century that similar well-preserved abelisaurids were described, including Aucasaurus, Majungasaurus and Skorpiovenator, allowing scientists to re-evaluate certain aspects of the anatomy of Carnotaurus.[upper-alpha 45] The holotype skeleton is displayed in the Argentine Museum of Natural Sciences, Bernardino Rivadavia;[upper-alpha 46] replicas can be seen in this and other museums around the world.[21] Sculptors Stephen and Sylvia Czerkas manufactured a life-sized sculpture of Carnotaurus that was previously on display at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. This sculpture, ordered by the museum during the mid-1980s, is probably the first life restoration of a theropod showing accurate skin.[20][37]

Age and paleoecology

Originally, the rocks in which Carnotaurus was found were assigned to the upper part of the Gorro Frigio Formation, which was considered to be approximately 100 million years old (Albian or Cenomanian stage).[31][upper-alpha 47] Later, they were realized to pertain to the much younger La Colonia Formation,[35] dating 72 to 69.9 million years ago (Late Cretaceous, Lower Maastrichtian stage).[upper-alpha 48] Thus, Carnotaurus was the latest South American abelisaurid known.[16] By the Late Cretaceous, South America was already isolated from both Africa and North America.[38]

The La Colonia Formation is exposed over the southern slope of the North Patagonian Massif.[39] Most vertebrate fossils, including Carnotaurus, come from the formation's middle section (called the middle facies association).[39] This part likely represents the deposits of an environment of estuaries, tidal flats or coastal plains.[39] The climate would have been seasonal with both dry and humid periods.[39] The most common vertebrates collected include ceratodontid lungfish, turtles, crocodiles, plesiosaurs, dinosaurs, lizards, snakes and mammals.[40] Some of the snakes that have been found belong to the families Boidae and Madtsoidae, such as Alamitophis argentinus.[41] Turtles are represented by at least five taxa, four from Chelidae (Pleurodira) and one from Meiolaniidae (Cryptodira).[42] Among the marine reptiles is the plesiosaur Sulcusuchus erraini of the family Polycotylidae.[42] Mammals are represented by Reigitherium bunodontum, which was considered the first record of a South American docodont,[39] and Argentodites coloniensis, possibly of Multituberculata.[43] In 2011, the discovery of a new enantiornithine bird from the La Colonia Formation was announced.[44]

Paleobiology

Function of the horns

Carnotaurus is the only known carnivorous bipedal animal with a pair of horns on the frontal bone.[45] The use of these horns is not entirely clear; several interpretations have revolved around use in fighting conspecifics, in display, or in killing prey.

Greg Paul (1988) proposed that the horns were butting weapons and that the small orbita would have minimized the possibility of hurting the eyes while fighting.[13] Gerardo Mazzetta and colleagues (1998) suggested that Carnotaurus used its horns in a way similar to rams. They calculated that the neck musculature was strong enough to absorb the force of two individuals colliding with their heads frontally at a speed of 5.7 m/s each.[8] Fernando Novas (2009) interpreted several skeletal features as adaptations for delivering blows with the head.[upper-alpha 49] He suggested that the shortness of the skull might have made head movements quicker by reducing the moment of inertia, while the muscular neck would have allowed strong head blows. He also noted an enhanced rigidity and strength of the spinal column that may have evolved to withstand shocks conducted by the head and neck.[upper-alpha 50]

Other studies suggest that rivaling Carnotaurus did not deliver rapid head blows, but pushed slowly against each other with the upper sides of their skulls.[45][46] Thus, the horns may have been a device for the distribution of compression forces without damage to the brain.[45] This is supported by the flattened upper sides of the horns, the strongly fused bones of the top of the skull, and the inability of the skull to survive rapid head blows.[45]

Gerardo Mazzetta and colleagues (1998) propose that the horns might also have been used to injure or kill small prey. Though horn cores are blunt, they may have had a similar form to modern bovid horns if there was a keratinous covering. However, this would be the only reported example of horns being used as hunting weapons in animals.[8]

Jaw function and diet

Analysis of the jaw structure of Carnotaurus by Mazzetta and colleagues (1998, 2004, 2009) suggests that the animal was capable of quick bites, but not strong ones.[8][9][45] Quick bites are more important than strong bites when capturing small prey, as shown by studies of modern-day crocodiles.[45] These researchers also noted a high degree of flexibility (kinesis) within the skull and especially the lower jaw, somewhat similar to modern snakes. Elasticity of the jaw would have allowed Carnotaurus to swallow small prey items whole. In addition, the front part of the lower jaw was hinged, and thus able to move up and down. When pressed downwards, the teeth would have projected forward, allowing Carnotaurus to spike small prey items; when the teeth were curved upwards, the now backward projecting teeth would have hindered the caught prey from escaping.[8] Mazzetta and colleagues also found that the skull was able to withstand forces that appear when tugging on large prey items.[45] Carnotaurus may therefore have fed mainly on relatively small prey, but also was able to hunt large dinosaurs.[45]

This interpretation was questioned by François Therrien and colleagues (2005), who found that the biting force of Carnotaurus was twice that of the American alligator, which may have the strongest bite of any living tetrapod. These researchers also noted analogies with modern Komodo dragons: the flexural strength of the lower jaw decreases towards the tip linearly, indicating that the jaws were not suited for high precision catching of small prey but for delivering slashing wounds to weaken big prey. As a consequence, according to this study, Carnotaurus must have mainly preyed upon large animals, possibly by ambush.[47]

Robert Bakker (1998) found that Carnotaurus mainly fed upon very large prey, especially sauropods. As he noted, several adaptations of the skull—the short snout, the relatively small teeth and the strong back of the skull (occiput)—had independently evolved in Allosaurus. These features suggest that the upper jaw was used like a serrated club to inflict wounds; big sauropods would have been weakened by repeated attacks.[48]

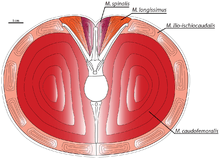

Locomotion

Mazzetta and colleagues (1998, 1999) presumed that Carnotaurus was a swift runner, arguing that the thigh bone was adapted to withstand high bending moments while running. The ability of an animal's leg to withstand those forces limits its top speed. The running adaptations of Carnotaurus would have been better than those of a human, although not nearly as good as those of an ostrich.[upper-alpha 51][49] Scientists calculate that Carnotaurus had a top speed of up to 48–56 km (30–35 mi) per hour.[50]

In dinosaurs, the most important locomotor muscle was located in the tail. This muscle, called the caudofemoralis, attaches to the fourth trochanter, a prominent ridge on the thigh bone, and pulls the thigh bone backwards when contracted. Scott Persons and Phil Currie (2011) note that in the tail vertebrae of Carnotaurus, the caudal ribs did not protrude horizontally ("T-shaped"), but were angled against the vertical axis of the vertebrae, forming a "V". This would have provided additional space for a caudofemoralis muscle larger than in any other theropod—the muscle mass was calculated at 111 to 137 kilograms (245 to 302 lb) per leg. Therefore, Carnotaurus could have been one of the fastest large theropods.[16] While the caudofemoralis muscle was enlarged, the epaxial muscles situated above the caudal ribs would have been proportionally smaller. These muscles, called the longissimus and spinalis muscle, were responsible for tail movement and stability. To maintain tail stability in spite of reduction of these muscles, the caudal ribs bear forward projecting processes interlocking the vertebrae with each other and with the pelvis, stiffening the tail. As a consequence, the ability to make tight turns would have been diminished, because the hip and tail had to be turned simultaneously, unlike in other theropods.[16]

See also

- Timeline of ceratosaur research

Notes

- p. 38 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 162 in Juárez Valieri et al. (2010)[3]

- p. 191 in Carrano and Sampson (2008)[5]

- p. 162 in Juárez Valieri et al. (2010)[3]

- p. 163 in Juárez Valieri et al. (2010)[3]

- p. 556 in Calvo et al. (2004)[6]

- p. 191 in Carrano and Sampson (2008)[5]

- p. 30 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 187 in Mazzetta et al. (1998)[8]

- p. 79 in Mazzetta et al. (2004)[9]

- p. 276 in Novas (2009)[10]

- p. 28–32 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 8 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 191 in Carrano and Sampson (2008)[5]

- p. 3 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 3 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 4–5 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 5 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 3 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 191 in Mazzetta et al. (1998)[8]

- p. 255 in Novas (2009)[10]

- p. 6 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 6 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 6 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 191 in Carrano and Sampson (2008)[5]

- pp. 257 in Novas (2009)[10]

- p. 1276 in Ruiz et al. (2011)[17]

- p. 32 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 32 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- pp. 264–299 in Novas (2009)[10]

- pp. 264–299 in Novas (2009)[10]

- p. 32 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 276–277 in Novas (2009)[10]

- pp. 256–261 in Novas (2009)[10]

- pp. 188–189 and 202 in Carrano and Sampson (2008)[5]

- p. 279 in Novas (2009)[10]

- p. 202 in Carrano and Sampson (2008)[5]

- p. 202 in Carrano and Sampson (2008)[5]

- p. 202 in Carrano and Sampson (2008)[5]

- p. 276 in Novas (2009)[10]

- p. 2 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 2 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 191 in Carrano and Sampson (2008)[5]

- p. 2 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 191 in Carrano and Sampson (2008)[5]

- p. 3 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 3 in Bonaparte (1990)[2]

- p. 276 in Novas (2009)[10]

- pp. 259–261 in Novas (2009)[10]

- pp. 260–261 in Novas (2009)[10]

- p. 186 and 190 in Mazzetta et al. (1998)[8]

References

- Candeiro, Carlos Roberto dos Anjos; Martinelli, Agustín Guillermo. "Abelisauroidea and carchardontosauridae (theropoda, dinosauria) in the cretaceous of south america. Paleogeographical and geocronological implications". Uberlândia. 17 (33): 5–19.

- Bonaparte, José F.; Novas, Fernando E.; Coria, Rodolfo A. (1990). "Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte, the horned, lightly built carnosaur from the Middle Cretaceous of Patagonia" (PDF). Contributions in Science. 416: 1–41.

- Juárez Valieri, Rubén D.; Porfiri, Juan D.; Calvo, Jorge O. (2010). "New information on Ekrixinatosaurus novasi Calvo et al. 2004, a giant and massively-constructed Abelisauroid from the "Middle Cretaceous" of Patagonia". Paleontologıa y Dinosaurios en América Latina: 161–169.

- Paul, Gregory S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691137209.

- Carrano, Matthew T.; Sampson, Scott D. (January 2008). "The Phylogeny of Ceratosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (2): 183–236. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002246.

- Calvo, Jorge O.; Rubilar-Rogers, David; Moreno, Karen (2004). "A new Abelisauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from northwest Patagonia" (PDF). Ameghiniana. 41 (4): 555–563. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-09.

- Grillo, O.N.; Delcourt, R. (2016). "Allometry and body length of abelisauroid theropods: Pycnonemosaurus nevesi is the new king". Cretaceous Research. 69: 71–89. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.09.001.

- Mazzetta, Gerardo V.; Fariña, Richard A.; Vizcaíno, Sergio F. (1998). "On the palaeobiology of the South American horned theropod Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte" (PDF). Gaia. 15: 185–192.

- Mazzetta, Gerardo V.; Christiansen, Per; Fariña, Richard A. (2004). "Giants and Bizarres: Body size of some southern South American Cretaceous dinosaurs" (PDF). Historical Biology. 16 (2): 71–83. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.1650. doi:10.1080/08912960410001715132.

- Novas, Fernando E. (2009). The age of dinosaurs in South America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35289-7.

- Sampson, Scott D.; Witmer, Lawrence M. (2007). "Craniofacial Anatomy of Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) From the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (sp8): 95–96. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[32:CAOMCT]2.0.CO;2.

- Paulina Carabajal, Ariana (2011). "The braincase anatomy of Carnotaurus sastrei (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (2): 378–386. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.550354.

- Paul, Gregory S. (1988). Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. pp. 284–285. ISBN 978-0-671-61946-6.

- Hartman, Scott (2012). "Carnotaurus – delving into self-parody?". Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- Méndez, Ariel (2014). "The cervical vertebrae of the Late Cretaceous abelisaurid dinosaur Carnotaurus sastrei" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 59 (1): 99–107. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0129. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-04-03. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- Persons, W.S.; Currie, P.J. (2011). Farke, Andrew Allen (ed.). "Dinosaur Speed Demon: The caudal musculature of Carnotaurus sastrei and implications for the evolution of South American abelisaurids". PLoS ONE. 6 (10): e25763. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625763P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025763. PMC 3197156. PMID 22043292.

- Ruiz, Javier; Torices, Angélica; Serrano, Humberto; López, Valle (2011). "The hand structure of Carnotaurus sastrei (Theropoda, Abelisauridae): implications for hand diversity and evolution in abelisaurids" (PDF). Palaeontology. 54 (6): 1271–1277. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01091.x.

- Agnolin, Federico L.; Chiarelli, Pablo (June 2010). "The position of the claws in Noasauridae (Dinosauria: Abelisauroidea) and its implications for abelisauroid manus evolution". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 84 (2): 293–300. doi:10.1007/s12542-009-0044-2.

- Senter, P. (2010). "Vestigial skeletal structures in dinosaurs". Journal of Zoology. 280 (4): 60–71. Bibcode:2010JZoo..281..263G. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00640.x.

- Czerkas, Stephen A.; Czerkas, Sylvia J. (1997). "The Integument and Life Restoration of Carnotaurus". In Wolberg, D. I.; Stump, E.; Rosenberg, G. D. (eds.). Dinofest International. Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia. pp. 155–158.

- Glut, Donald F. (2003). "Carnotaurus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. 3rd Supplement. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 274–276. ISBN 978-0-7864-1166-5.

- Canale, Juan I.; Scanferla, Carlos A.; Agnolin, Federico; Novas, Fernando E. (2009). "New carnivorous dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of NW Patagonia and the evolution of abelisaurid theropods". Naturwissenschaften. 96 (3): 409–14. Bibcode:2009NW.....96..409C. doi:10.1007/s00114-008-0487-4. hdl:11336/52024. PMID 19057888.

- Coria, Rodolfo A.; Chiappe, Luis M.; Dingus, Lowell (2002). "A new close relative of Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte 1985 (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (2): 460. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0460:ANCROC]2.0.CO;2.

- Ezcurra, Martín D.; Agnolin, Federico L.; Novas, Fernando E. (2010). "An abelisauroid dinosaur with a non-atrophied manus from the Late Cretaceous Pari Aike Formation of southern Patagonia" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2450: 14. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2450.1.1.

- Sereno, Paul C.; Wilson, Jeffrey A.; Conrad, Jack L. (7 July 2004). "New dinosaurs link southern landmasses in the Mid-Cretaceous". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1546): 1325–1330. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2692. PMC 1691741. PMID 15306329.

- Tykoski, Ronald B.; Rowe, Timothy (2004). "Ceratosauria". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (Second ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- Wilson, Jeffrey A.; Sereno, Paul C.; Srivastava, Suresh; Bhatt, Devendra K.; Khosla, Ashu; Sahni, Ashok (2003). "A new abelisaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Lameta Formation (Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) of India". Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology. 31 (1): 25. hdl:2027.42/48667.

- Sereno, Paul (2005). "Carnotaurinae". Taxon Search. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Sereno, Paul (2005). "Carnotaurini". Taxon Search. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Salgado, Leonardo; Bonaparte, José F. (1991). "Un nuevo sauropodo Dicraeosauridae, Amargasaurus cazaui gen. et sp. nov., de la Formacion La Amarga, Neocomiano de la Provincia del Neuquén, Argentina". Ameghiniana (in Spanish). 28 (3–4): 334.

- Bonaparte, José F. (1985). "A horned Cretaceous carnosaur from Patagonia". National Geographic Research. 1 (1): 149–151.

- Yong, Ed (October 18, 2011). "Butch tail made Carnotaurus a champion dinosaur sprinter". National Geographic. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- Headden, Jaime A. (19 September 2006). "Re: Carnotaurus sastrei etymology". Dinosaur Mailing List.

- Bonaparte, José F. (1991). "The gondwanian theropod families Abelisauridae and Noasauridae". Historical Biology. 5: 1. doi:10.1080/10292389109380385.

- Bonaparte, José F. (1996). "Cretaceous tetrapods of Argentina". Münchener Geowissenschaftliche Abhandlung. A (30): 89.

- Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Carnotaurus". Dinosaurs, the encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers. pp. 256–259. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

- Glut, Donald F. (2000). "Carnotaurus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. 1st Supplement. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 165–167. ISBN 978-0-7864-0591-6.

- Le Loeuff, Jean (1997). "Biogeography". In Padian, Kevin; Currie, Philip J. (eds.). Encyclopedia of dinosaurs. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 51–56. ISBN 978-0-12-226810-6.

- Pascual, Rosendo; Goin, Francisco J.; González, Pablo; Ardolino, Alberto; Puerta, Pablo F. (2000). "A highly derived docodont from the Patagonian Late Cretaceous: evolutionary implications for Gondwanan mammals". Geodiversitas. 22 (3): 395–414.

- Sterli, Juliana; De la Fuente, Marcelo S. (2011). "A new turtle from the La Colonia Formation (Campanian–Maastrichtian), Patagonia, Argentina, with remarks on the evolution of the vertebral column in turtles". Palaeontology. 54 (1): 65. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.01002.x.

- Albino, Adriana M. (2000). "New record of snakes from the Cretaceous of Patagonia (Argentina)". Geodiversitas. 22 (2): 247–253.

- Gasparini, Zulma; De la Fuente, Marcelo (2000). "Tortugas y Plesiosaurios de la Formación La Colonia (Cretácico Superior) de Patagonia, Argentina". Revista Española de Paleontología (in Spanish). 15 (1): 23.

- Kielan−Jaworowska, Zofia; Ortiz−Jaureguizar, Edgardo; Vieytes, Carolina; Pascual, Rosendo; Goin, Francisco J. (2007). "First ?cimolodontan multi−tuberculate mammal from South America" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 52 (2): 257–262.

- Lawver, Daniel R.; Debee, Aj M.; Clarke, Julia A.; Rougier, Guillermo W. (1 January 2011). "A New Enantiornithine Bird from the Upper Cretaceous La Colonia Formation of Patagonia, Argentina". Annals of Carnegie Museum. 80 (1): 35–42. doi:10.2992/007.080.0104.

- Mazzetta, Gerardo V.; Cisilino, Adrián P.; Blanco, R. Ernesto; Calvo, Néstor (2009). "Cranial mechanics and functional interpretation of the horned carnivorous dinosaur Carnotaurus sastrei". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (3): 822–830. doi:10.1671/039.029.0313.

- Chure, Daniel J. (1998). "On the orbit of theropod dinosaurs". Gaia. 15: 233–240.

- Therrien, François; Henderson, Donald; Ruff, Christopher (2005). "Bite Me – Biomechanical Models of Theropod Mandibles and Implications for Feeding Behavior". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The carnivorous dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 179–198, 228. ISBN 978-0-253-34539-4.

- Bakker, Robert T. (1998). "Brontosaur killers: Late Jurassic allosaurids as sabre-tooth cat analogues" (PDF). Gaia. 15: 145–158.

- Mazzetta, Gerardo V.; Farina, Richard A. (1999). "Estimacion de la capacidad atlética de Amargasaurus cazaui Salgado y Bonaparte, 1991, y Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte, 1985 (Saurischia, Sauropoda-Theropoda)". XIV Jornadas Argentinas de Paleontologia de Vertebrados, Ameghiniana (in Spanish). 36 (1): 105–106.

- "Predatory dinosaur was fearsomely fast". CBC News. October 21, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carnotaurus. |

- The bite of Carnotaurus at Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata. (in Spanish)

- Skeletal reconstruction by Scott Hartman

.jpg)

.png)