Belt and Road Initiative

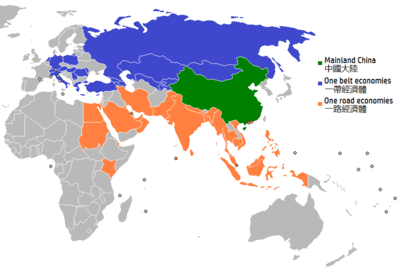

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI, or B&R[1]) is a global development strategy adopted by the Chinese government in 2013 involving infrastructure development and investments in nearly 70 countries and international organizations in Asia, Europe, and Africa.[2][3]

| Formation | 2013 2017 (Forum) |

|---|---|

| Purpose | "to construct a unified large market and make full use of both international and domestic markets, through cultural exchange and integration, to enhance mutual understanding and trust of member nations, ending up in an innovative pattern with capital inflows, talent pool, and technology database" |

| Location | |

Region served | Asia Africa Europe Middle East Americas |

Leader |

| The Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 丝绸之路经济带和21世纪海上丝绸之路 | ||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 絲綢之路經濟帶和21世紀海上絲綢之路 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| One Belt, One Road (OBOR) | |||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 一带一路 | ||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 一帶一路 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

.svg.png) |

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of China |

|

Leadership

|

|

|

United Front

|

|

Ideology

|

|

|

Legislative

|

|

|

Executive

|

|

Military

|

|

Supervision

|

|

|

Publicity

|

|

|

Cross-Strait relations

|

|

Foreign relations

|

|

Related topics

|

|

The leader of the People's Republic of China, Xi Jinping, originally announced the strategy during official visits to Indonesia and Kazakhstan in 2013. "Belt" refers to the overland routes for road and rail transportation, called "the Silk Road Economic Belt"; whereas "road" refers to the sea routes, or the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.[4]

Formerly known as One Belt One Road (OBOR) (Chinese: 一带一路, short for the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road (丝绸之路经济带和21世纪海上丝绸之路)[5]), it has been referred to as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) since 2016 when the Chinese government considered the emphasis on the word "one" was prone to misinterpretation.[6] However, "One Belt One Road" (一带一路) is still used in Chinese-language media.[7]

The Chinese government calls the initiative "a bid to enhance regional connectivity and embrace a brighter future".[8] Some observers see it as a push for Chinese dominance in global affairs with a China-centered trading network.[9][10] The project has a targeted completion date of 2049,[11] which coincides with the 100th anniversary of the People's Republic of China.

History

The initiative was unveiled by Chinese paramount leader Xi Jinping in September and October 2013 during visits to Kazakhstan and Indonesia,[12] and was thereafter promoted by Premier Li Keqiang during state visits to Asia and Europe. The initiative was given intensive coverage by Chinese state media, and by 2016 often being featured in the People's Daily.[13]

Initially, the initiative was termed One Belt One Road Strategy, but officials decided that the term "strategy" would create suspicions so they opted for the more inclusive term "initiative" in its translation.[14]

Initial objectives

The stated objectives are "to construct a unified large market and make full use of both international and domestic markets, through cultural exchange and integration, to enhance mutual understanding and trust of member nations, ending up in an innovative pattern with capital inflows, talent pool, and technology database."[15] The initial focus has been infrastructure investment, education, construction materials, railway and highway, automobile, real estate, power grid, and iron and steel.[16] Already, some estimates list the Belt and Road Initiative as one of the largest infrastructure and investment projects in history, covering more than 68 countries, including 65% of the world's population and 40% of the global gross domestic product as of 2017.[17][18]

The Belt and Road Initiative addresses an "infrastructure gap" and thus has potential to accelerate economic growth across the Asia Pacific area, Africa and Central and Eastern Europe: a report from the World Pensions Council (WPC) estimates that Asia, excluding China, requires up to US$900 billion of infrastructure investments per year over the next decade, mostly in debt instruments, 50% above current infrastructure spending rates.[19] The gaping need for long term capital explains why many Asian and Eastern European heads of state "gladly expressed their interest to join this new international financial institution focusing solely on 'real assets' and infrastructure-driven economic growth".[20]

Political control

The Leading Group for advancing the Development of One Belt One Road was formed sometime in late 2014, and its leadership line-up publicized on 1 February 2015. This steering committee reports directly into the State Council of the People's Republic of China and is composed of several political heavyweights, evidence of the importance of the program to the government. Then Vice-Premier Zhang Gaoli, who was also a member of the 7-man Politburo Standing Committee then, was named leader of the group, with Wang Huning, Wang Yang, Yang Jing, and Yang Jiechi being named deputy leaders.[21]

In March 2014, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang called for accelerating the Belt and Road Initiative along with the Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar Economic Corridor[22] and the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor in his government work report presented to the annual meeting of the country's legislature.

On 28 March 2015, China's State Council outlined the principles, framework, key areas of cooperation and cooperation mechanisms with regard to the initiative.[23]

Infrastructure networks

The Belt and Road Initiative is about improving the physical infrastructure along land corridors that roughly equate to the old silk road. These are the belts in the title, and a maritime silk road.[24] Infrastructure corridors encompassing around 60 countries, primarily in Asia and Europe but also including Oceania and East Africa, will cost an estimated US$4–8 trillion.[25][26] The initiative has been contrasted with the two US-centric trading arrangements, the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership.[26] The projects receive financial support from the Silk Road Fund and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank while they are technically coordinated by the B&R Summit Forum. The land corridors include:[24]

- The New Eurasian Land Bridge, which runs from Western China to Western Russia through Kazakhstan, and includes the Silk Road Railway through China's Xinjiang Autonomous Region, Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Poland and Germany.

- The China–Mongolia–Russia Corridor, which will run from Northern China to the Russian Far East. The Russian government-established Russian Direct Investment Fund and China's China Investment Corporation, a Chinese government investment agency, partnered in 2012 to create the Sino-Russian Investment Fund, which concentrates on opportunities in bilateral integration.[27][28]

- The China–Central Asia–West Asia Corridor, which will run from Western China to Turkey.

- The China–Indochina Peninsula Corridor, which will run from Southern China to Singapore.

- The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) (Chinese: 中国-巴基斯坦经济走廊; Urdu: پاكستان-چین اقتصادی راہداری) which is also classified as "closely related to the Belt and Road Initiative",[29] a US$62 billion collection of infrastructure projects throughout Pakistan[30][31][32] which aims to rapidly modernize Pakistan's transportation networks, energy infrastructure, and economy.[31][32][33][34] On 13 November 2016, CPEC became partly operational when Chinese cargo was transported overland to Gwadar Port for onward maritime shipment to Africa and West Asia.[35]

Silk Road Economic Belt

Xi Jinping visited Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan, and Southeast Asia in September and October 2013, and proposed jointly building a new economic area, the Silk Road Economic Belt (Chinese: 丝绸之路经济带)[37] Essentially, the "belt" includes countries located on the original Silk Road through Central Asia, West Asia, the Middle East, and Europe.[38] The initiative would create a cohesive economic area by building both hard infrastructure such as rail and road links and soft infrastructure such as the trade agreements and a common commercial legal structure with a court system to police the agreements.[4] It would increase cultural exchanges and expand trade. Outside this zone, which is largely analogous to the historical Silk Road, is an extension to include South Asia and Southeast Asia.

Many of the countries that are part of this belt are also members of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Three belts are proposed. The North belt would go through Central Asia and Russia to Europe. The Central belt passes through Central Asia and West Asia to the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean. The South belt runs from China to Southeast Asia, South Asia, to the Indian Ocean through Pakistan. The strategy will integrate China with Central Asia through Kazakhstan's Nurly Zhol infrastructure program.[39]

21st Century Maritime Silk Road

The "21st Century Maritime Silk Road" (Chinese: 21世纪海上丝绸之路), or just the Maritime Silk Road, is the sea route 'corridor.'[4] It is a complementary initiative aimed at investing and fostering collaboration in Southeast Asia, Oceania and Africa through several contiguous bodies of water: the South China Sea, the South Pacific Ocean, and the wider Indian Ocean area.[40][41][42] It was first proposed in October 2013 by Xi Jinping in a speech to the Indonesian Parliament.[43] Like the Silk Road Economic Belt initiative, most countries have joined the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Ice Silk Road

In addition to the Maritime Silk Road, Russia and China are reported to have agreed jointly to build an 'Ice Silk Road' along the Northern Sea Route in the Arctic, along a maritime route which Russia considers to be part of its internal waters.[44][45]

China COSCO Shipping Corp. has completed several trial trips on Arctic shipping routes, and Chinese and Russian companies are seeking cooperation on oil and gas exploration in the area and to advance comprehensive collaboration on infrastructure construction, tourism and scientific expeditions.[45]

Russia together with China approached the practical discussion of the global infrastructure project Ice Silk Road. This was stated by representatives of VnesheconomBank at the International conference Development of the shelf of Russia[46] and the CIS — 2019 (Petroleum Offshore of Russia), held in Moscow.

The delegates of the conference were representatives of the leadership of Russian and corporations (Gazprom, Lukoil, RosAtom, Rosgeologiya, VnesheconomBank, Morneftegazproekt, Murmanshelf, Russian Helicopters, etc.), as well as foreign auditors (Deloitte, member of the world Big Four) and consulting centers (Norwegian Rystad Energy and others.).[47]

Super grid

The super grid project aims to develop six ultra high voltage electricity grids across China, north-east Asia, Southeast Asia, south Asia, central Asia and west Asia. The wind power resources of central Asia would form one component of this grid.[48][49]

Former

The Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar (BCIM) Economic Corridor, which runs from southern China to Myanmar and was initially officially classified as "closely related to the Belt and Road Initiative".[29] Since the 2nd Belt and Road Forum in 2019, BCIM has been dropped from the list of covered projects due to India's refusal to participate in the Belt and Road Initiative.[50]

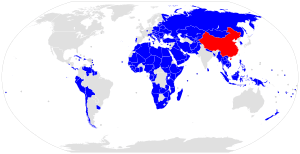

Project achievement

China has signed cooperational document on the belt and road initiative with 138 countries and 30 international organisations.[51] In terms of infrastructure construction, China and the countries along the Belt and Road have carried out effective cooperation in ports, railways, highways, power stations, aviation and telecommunications.[52]

BRI by Country, $ billion 2014-2018

Construction — Investment

1. Pakistan 31.9 — Singapore 24.3

2. Nigeria 23.2 — Malaysia 14.1

3. Bangladesh 17.5 — Russian Federation 10.4

4. Indonesia 16.8 — Indonesia 9.4

5. Malaysia 15.8 — South Korea 8.1

6. Egypt 15.3 — Israel 7.9

7. UAE 14.7 — Pakistan 7.6

Source [53]

Africa

Djibouti

Djibouti's Doraleh Multi-purpose Port and the Hassan Gouled Aptidon international airport.[54][55] Djibouti, a remote country at the Horn of Africa, is at the heart of China's multibillion-dollar "Belt and Road Initiative", supporting Beijing's juggling of commercial and military objectives amid Western suspicions about its motives.

Egypt

Egypt's New Administrative Capital is a landmark for the Belt and Road Initiative.[56]

Ethiopia

Ethiopia's Eastern Industrial Zone is a manufacturing hub outside Addis Ababa that was built by China and occupied by factories of Chinese manufacturers.[57] According to Chinese media and the vice director of the industrial zone, there were 83 companies resident within the zone, of which 56 had started production.[58] However, a study in Geoforum noted that the EIZ has yet to serve as a catalyst for Ethiopia's overall economic development due to many factors including poor infrastructure outside the zone. Discrepancies between the two countries' industries also mean that Ethiopia cannot benefit from direct technological transfer and innovation.[59]

From October 2011 to February 2012, Chinese companies were contracted to supersede the century-old Ethio-Djibouti Railways by constructing a new electric standard gauge Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway. The new railway line, stretching more than 750 kilometres (470 mi) and travelling at 120 km/h (75 mph), shortens the journey time between Addis Ababa and Dijbouti from three days to about 12 hours.[60] The first freight service began in November 2015 and passenger service followed in October 2016.[61] On China–Ethiopia cooperation on international affairs, China's Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that China and Ethiopia are both developing countries, and both countries are faced with a complicated international environment. He stated that the partnership will be a model at the forefront of developing China–Africa relations.[62]

Kenya

In May 2014, Premier Li Keqiang signed a cooperation agreement with the Kenyan government to build the Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway connecting Mombasa to Nairobi. The railway cost US$3.2bn and was Kenya's biggest infrastructure project since independence. The railway was claimed to cut the journey time from Mombasa to Nairobi from 9 hours by bus or 12 hours on the previous railway to 4.5 hours. In May 2017, Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta called the 470 km railway a new chapter that "would begin to reshape the story of Kenya for the next 100 years".[63] According to Kenya Railways Corporation, the railway carried 1.3 million Kenyans with a 96.7% seat occupancy and 600,000 tons of cargo in its first year of operation. Chinese media claim that the railway line boosted the country's GDP by 1.5% and created 46,000 jobs for locals and trained 1,600 railway professionals.[64]

Nigeria

On 12 January 2019, Nigeria's first standard gauge railway, which has been successfully operated for 900 days, had no major accidents since its inception. With the successful completion of the railway construction by China Civil Engineering Construction Company (CCECC), the Abuja Kaduna train service began commercial operation on 27 July 2016. The Abuja-Kaduna Railway Line is one of the first standard railroad railway modernization projects (SGRMP) in Nigeria. This is the first part of the Lagos-Kano standard metrics project, which will connect the business centres of Nigeria with the economic activity centres of the northwestern part of the country.[65]

In a resolution of the Johannesburg Summit of the China-Africa Cooperation Forum in 2015, the Chinese government promised to provide satellite television to 10,000 African villages. It is reported that each of the 1,000 selected villages in Nigeria, the most populous country in Africa, will receive two sets of solar projection television systems and a set of solar 32-inch digital TV integrated terminal systems. A total of 20,000 Nigerian rural families will benefit from the project. Kpaduma, an underdeveloped rural community on the edge of the Nigerian capital of Abuja, is familiar with analog TV and has no chance to see the satellite TV channels enjoyed by people in Nigerian towns. The implementation of the project will create more jobs, 1,000 Nigerians in selected villages have received training on how to install, recharge and operate satellite TV systems.[66]

Sudan

In Sudan, China has helped the country establish its oil industry and provided agricultural assistance for the cotton industry.

Future plans include developing railways, roads, ports, a nuclear power station, solar power farms and more dams for irrigation and electricity generation.[67]

Europe

Freight train services between China and Europe were initiated in March 2011.[68] The service's first freight route linked China to Tehran. The China–Britain route was launched in January 2017[69] As of 2018, the network had expanded to cover 48 Chinese cities and 42 European destinations, delivering goods between China and Europe. The 10,000th trip was completed on 26 August 2018 with the arrival of freight train X8044 in Wuhan, China from Hamburg, Germany.[70] The network was further extended southward to Vietnam in March 2018.[71]

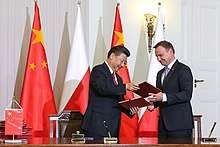

Poland

Poland was one of the first European countries to sign a Memorandum of Understanding with China about the BRI in 2015.[72] Poland's President Duda said that he hopes Poland will become a gateway to Europe for China.[73]

Greece

The foreign ministers of China and Greece signed a Memorandum of Understanding related to further cooperation under the Belt and Road initiative on 29 August 2018. COSCO revitalized and currently runs the Port of Piraeus.[74][38][75] Both China and Greece see each other as natural allies in developing the Belt & Road", President Xi said at the start of a state visit aimed at deepening cooperation with Greece across the board, adding his desire to "keep the momentum going" and "reinforce" bilateral relations

Portugal

During president Xi's visit to Lisbon in December 2018, the Southern European nation signed a Memorandum of Understanding with China.[76]

Italy

In March 2019, Italy became the first G7 Nation to join China's Belt and Road Initiative.[77][78]

Austria

During a visit of Chancellor Kurz to China in April 2019, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed on Austria's cooperation in the BRI project. According to Kurz, Austria "support[s] the One Belt One Road initiative and [is] trying to forge a close economic cooperation [with China]. Austria has know-how and expertise to offer in many areas where China is looking for the same".[79]

Luxembourg

On 27 March 2019, Luxembourg signed an agreement with China to cooperate on Belt and Road Initiative.[80]

Switzerland

On 29 April 2019, during his visit to Beijing, Swiss President Ueli Maurer signed a Memorandum of Understanding with China under the Belt and Road Initiative.[81]

Caucasus

Armenia

On 4 April 2019, the President of Armenia Armen Sarkissian received a delegation led by Shen Yueyue, Vice-Chairwoman of the National People's Congress Standing Committee of China in Yerevan, Armenia. President Sarkissian stated that Armenia and China are ancient countries with centuries-old tradition of cooperation since the existence of the Silk Road. The President noted the development of cooperation in the 21st century in the sidelines of the One Belt One Road program initiated by the top leadership of China and stated that "It’s time for Armenia to become part of the new Silk Road".[82]

Azerbaijan

On 25-27 April 2019, the Second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation was held in Beijing, China. A delegation led by President of the Republic of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev attended the Forum. The event brought together heads of governments from 37 countries, including Azerbaijan, Russia, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Austria, Belarus, the Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Serbia, Singapore, the UAE, and others, as well as heads of international organizations. In his speech, the President Ilham Aliyev stated that, “From the very beginning Azerbaijan supported the Belt and Road initiative put forward by President Xi Jinping. This initiative not only provides transportation of productivity, it strengthens ties between different countries, serve the course of dialogue and cooperation, creates new opportunities for international trade.”

The creation of modern infrastructure is one of the priorities for Azerbaijan and will foster the flow of international trade by building bridges between Europe and Asia. Among these notable infrastructure projects are Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway and the Baku International Sea Trade Port (the Port of Baku) that play an important role in transportation in Eurasia. Currently, the Port of Baku has the capacity to handle 15 million tons of cargo, including 100000 TEU, which will grow to 25 million tons of cargo and 500000 TEU in the future. By investing in modern transportation and logistics infrastructure Azerbaijan not only transforms itself into an important transportation hub but also contributes to the cooperation with countries involved in East-West and North-South Corridors.

Georgia

On 25 April 2019, the Minister of Infrastructure and Regional Development of Georgia Maya Tskitishvili stated that, "One Belt-One Road initiative is important for Georgia and the country is actively involved in its development." She also noted that Georgia was among the first countries who signed the memorandum for developing the 'One Belt-One Road' initiative in March 2015.[83]

Russia and EEU

On 26 April 2019, the leaders of Russia and China called their countries "good friends" and vowed to work together in pursuing greater economic integration of Eurasia. On the sidelines of the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, Chinese President Xi Jinping and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin pledged to further strengthen economic and trade cooperation between the two sides. Vladimir Putin further stated that, "countries gathering under the Belt and Road Initiative and the Eurasian Economic Union share long-term strategic interests of peace and growth".[84]

On June 2019, Xi and Putin stated they were committed to the concept of building the "Great Eurasian Partnership". That took the form of Xi stating that he had agreed with Putin to link the Eurasian Economic Union with China's Belt & Road Initiative.[85][86]

The China–Belarus Industrial Park is a 91.5 km2 (35.3 sq mi) special economic zone established in Smolevichy, Minsk in 2013. According to the park's chief administrator, 36 international companies have settled in the park as of August 2018.[87] Chinese media said the park will create 6,000 jobs and become a real city with 10,000 residents by 2020.[88]

Asia

Central Asia

The five countries of Central Asia – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan – are an important part of the land route of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).[89] The Central Asia Data-Gathering and Analysis Team has identified 261 BRI projects within Central Asian nations with a minimum investment totaling more than 136 million USD. [90]

As of April 2019, Kazakhstan invested about $30 billion on infrastructure development, transport and logistics assets and competence as part of the Belt and Road Initiative. Due to Kazakhstan's infrastructure modernization, The Western Europe – Western China intercontinental highway now connects Europe and China through Russia and Kazakhstan.[91] Kazakhstan stands to receive a potential $5 billion annually in transit fees from goods moving through it to other markets.[92]

In Kyrgyzstan, 2011-2017 BRI projects total committed funds is equal to 4.1 billion USD. Employment created from established companies is not significant, making up only 0.1-0.3% of total employment in the country, just several thousand jobs. The weight of debt repayment for BRI projects will not be felt until the 2020s, because of the grace periods on most loans ranging from 5-11 years. Kyrgyzstan has the potential to benefit greatly from BRI; If tax legislation is handled well, particularly in manufacturing and transit projects, then revenue will be high.[93]

“From the perspective of Uzbekistan, the BRI could help open the corridor to the Persian Gulf, enabling expansion of commercial and trade routes for the country.” Exporting Uzbek goods to more regions is a highly attractive incentive for Uzbekistan. At the First Belt and Road Forum held in Beijing May, 2017 both presidents, Mirziyoyev of Uzbekistan and Xi Jinping of China, spoke positively of future collaboration in BRI advancement. During those meetings, the “two countries signed 115 deals worth more $23 billion on enhancing their cooperation in electrical power, oil production, chemicals, architecture, textiles, pharmaceutical engineering, transportation, infrastructure and agriculture.” [94] In 2019 Uzbekistan established a new government group in charge of aligning their own country’s development plan with China’s BRI ambitions. China is Uzbekistan’s largest trade partner (both in imports and exports) and has more than 1500 Chinese businesses within its territory. In 2018, “China-Uzbekistan trade surged 48.4 percent year-on-year, reaching 6.26 billion U.S. dollars.”[95]

“BRI projects in Tajikistan range from roads and railways to pipelines and power plants, even including traffic cameras.”[96] In 2018, “Tajikistan paid a Chinese company building a power plant with a gold mine; a few years earlier it swapped Beijing some land for debt.”[97]

Turkmenistan in most regards has been closed off to the world. However, Turkmenistan, because of a desire to see infrastructure and energy projects move ahead, is increasingly opening itself to the world. Turkmenistan doesn’t have the capabilities of seeing many of its projects come to fruition on its own. In June 2016, Gurbanguly, Turkmenistan’s president, approached Xi Jinping to discuss his desire to become more involved in BRI and seeing previously planned projects completed and or expanded. These projects include the Turkmenistan’s and China gas pipeline (with four lines, the fourth forthcoming), The International North-South transportation corridor (which provides railway connections between Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Iran, with another line connecting China to Iran via Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan), The Lapis Lazuli international transit corridor (rail connecting Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey), and the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan- Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline project. [98]

Hong Kong

During his 2016 policy address, Hong Kong chief executive Leung Chun-ying's announced his intention of setting up a Maritime Authority aimed at strengthening Hong Kong's maritime logistics in line with Beijing's economic policy.[99] Leung mentioned "One Belt, One Road" no fewer than 48 times during the policy address,[100] but details were scant.[101][102]

Indonesia

In 2016, China Railway International won a bid to build Indonesia's first high-speed rail, the 140 km (87 mi) Jakarta–Bandung High Speed Rail. It will shorten the journey time between Jakarta and Bandung from over three hours to forty minutes[103] The project, initially scheduled for completion in 2019, was delayed by land clearance issues.[104] 2000 locals are working on the project.

Laos

In Laos, construction of the 414 km (257 mi) Vientiane–Boten Railway began on 25 December 2016 and is scheduled to be completed in 2021. It is China's first overseas railway project that will connect to China's railway network.[105] Once operational, the Laos–China Railway will be Laos' longest and connect with Thailand to become part of the proposed Kunming–Singapore railway, extending from the Chinese city of Kunming and running through Thailand and Laos to terminate at Singapore.[106][107] It is estimated to cost US$5.95 billion with 70% of the railway owned by China, while Laos's remaining 30% stake will be mostly financed by loans from China.[108] However, it faces opposition within Laos due to the high cost of the project.[109]

Maldives

Maldives undertook a number of China funded projects under the Presidency of Abdullah Yameen (2013–18), including the China Maldives Friendship Bridge, The Velana International Airport and the artificial island of Hulhulmale. Many of these investments were made without adequate disclosures to the public on their cost and other terms. Under President Yameen, Maldives also amended its constitution to allow foreigners to own land in the archipelago - following which the island of Feydhoo Finholu was taken up on a long term lease by a Chinese company.[110]

Malaysia

Under the Premiership of Najib Razak, Malaysia signed multiple investment deals with China, including a US$27 billion East Coast Rail Link project, pipeline projects worth more than $3.1 billion, as well as a $100 billion Forest City in Johor.[111] During the 2018 Malaysian general election, then-opposition leader Mahathir Mohamad expressed disapproval of Chinese investment in Malaysia, comparing it to selling off the country to foreigners.[112] Upon election as Prime Minister of Malaysia, Mahathir labelled the China-funded projects as "unfair" deals authorized by former prime minister Najib Razak and would leave Malaysia "indebted" to China.[113] As was argued by Kit Wei Zheng of Citibank, he believed that the projects were likely to have been driven more by China's geopolitical interests than by the profit motive, such that China would have access to the Straits of Malacca.[114][115]

In August 2018, at the end of an official visit to China, Mahathir cancelled the East Coast Rail Link project and two other pipeline projects that had been awarded to the China Petroleum Pipeline Bureau. These had been linked to corruption at state fund 1Malaysia Development Berhad,[113] citing a need to reduce debt incurred by the previous government.[116][117][118][119]

It will be deferred until such time we can afford, and maybe we can reduce the cost also if we do it differently.

In addition, Mahathir also threatened to deny foreign buyers a long-stay visa, prompting a clarification by Housing Minister Zuraida Kamaruddin and the Prime Minister's Office.[120]

The project undergo negotiations for several months[121] and close to be cancelled off.[122] After rounds of negotiation and diplomatic mission, the ECRL project is resumed after Malaysia and China agreed to continue the project with reduced cost of RM 44 billion (US$10.68 billion) from the original of RM 65.5 billion.[123]

Pakistan

The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor is a major Belt and Road Initiative project encompassing investments in transport, energy and maritime infrastructure.

Sri Lanka

China's main investment in Sri Lanka was the Magampura Mahinda Rajapaksa Port, mostly funded by the Chinese government and built by two Chinese companies. It claims to be the largest port in Sri Lanka after the Port of Colombo and the "biggest port constructed on land to date in the country". It was initially intended to be owned by the Government of Sri Lanka and operated by the Sri Lanka Ports Authority, however it incurred heavy operational losses and the Sri Lankan government was unable to service the debt to China. In a debt restructuring plan on 9 December 2017, 70% of the port was leased and port operations were handed over to China for 99 years,[38] The deal gave the Sri Lankan government $1.4 billion, that they will be using to pay off the debt to China.[124][125][126] This led to accusations that China was practicing debt-trap diplomacy.[127]

The port's strategic location and subsequent ownership spurred concern over China's growing economic footprint in the Indian Ocean and speculation that it could be used as a naval base. The Sri Lankan government promised that it was intended "purely for civilian use".[128]

Colombo International Financial City built on land reclaimed from the Indian Ocean and funded with $1.4bn in Chinese investment is a special financial zone and another major Chinese investment in Sri Lanka.[129]

Thailand

In Thailand in 2005, the Chinese pharmaceutical company, Holley Group, and the Thai industrial estate developer, Amata Group, signed an agreement to develop the Thai–Chinese Rayong Industrial Zone. Since 2012, Chinese companies have also opened solar, rubber, and industrial manufacturing plants in the zone, and the zone expects the number to increase to 500 by 2021.[130] Chinese media have attributed this to Thailand's zero tax incentives on land use and export products as well as favorable labor costs, and claimed that the zone had created more than 3000 local jobs.[131]

In December 2017, China and Thailand began the construction of a high-speed railway that links the cities of Bangkok and Nakhon Ratchasima, which will be extended to Nong Khai to connect with Laos, as part of the planned Kunming–Singapore railway.[132] The first high-speed rail rail station in Thailand should be complete in 2021, with lines to enter service in 2024.[133]

Turkey

President Erdogan in his visit to China signed a Memorandum of Understanding with China under the Belt and Road Initiative and asked to increase trade volume, Referring to the fact that the volume of trade between the two countries reached $50 billion in the first phase, and in the second phase $100 billion in other goals. Thanks to the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway being integrated with Edirne-Kars high-speed train, projects with China will be able to transport their goods to Europe much sooner.[134]

North and South America

Panama was the first to sign BRI agreements, followed by Bolivia, Antigua and Barbuda, Trinidad and Tobago, and Guyana.[135]

Argentina

The Argentine-China Joint Hydropower Project will build two dams on the Santa Cruz River in southern Argentina: Condor Cliff and La Barrancosa. The China Gezhouba Group Corporation (CGGC) will be responsible for the project, which is expected to provide 5,000 direct and 15,000 indirect jobs in the country. It will generate 4,950 MWh of electricity, reducing the dependence on fossil fuels.[136]

Jamaica

On 11 April 2019, Jamaica and China signed a memorandum of understanding for Jamaica to join the BRI.[137]

Financial and research institutions

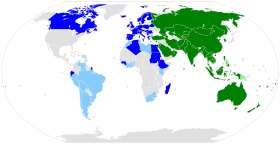

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB)

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

Prospective members (regional)

Members (regional)

Prospective members (non-regional)

Members (non-regional) |

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, first proposed in October 2013, is a development bank dedicated to lending for infrastructure projects. As of 2015, China announced that over one trillion yuan (US$160 billion) of infrastructure related projects were in planning or construction.[138]

The primary goals of AIIB are to address the expanding infrastructure needs across Asia, enhance regional integration, promote economic development and improve public access to social services.[139]

The Articles of Agreement of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) (the legal framework) were signed in Beijing on 29 June 2015. The proposed bank has an authorized capital of $100 billion, 75% of which will come from Asia and Oceania. China will be the single largest stakeholder, holding 26.63% of voting rights. The board of governors is AIIB's highest decision-making body.[140] The bank began operation on 16 January 2016, and approved its first four loans in June.[141]

Silk Road Fund

In November 2014, Xi Jinping announced a US$40 billion development fund, which would be separate from the banks and not part of the CPEC investment. The Silk Road Fund would invest in businesses rather than lend money to the projects. The Karot Hydropower Project, 50 km (31 mi) from Islamabad, Pakistan is the first project.[142] The Chinese government has promised to provide Pakistan with at least US$350 million by 2030 to finance this station. The Sanxia Construction Corporation commenced work in January 2016.

University Alliance of the Silk Road

A university alliance centered at Xi'an Jiaotong University aims to support the Belt and Road initiative with research and engineering, and to foster understanding and academic exchange.[143][144] The network extends beyond the economic zone, and includes a law school alliance to "serve the Belt and Road development with legal spirit and legal culture".[145]

Criticism

Background: Infrastructure-based development

China is a world leader in infrastructure investment.[146] In contrast with the general underinvestment in transportation infrastructure in the industrialized world after 1980 and the pursuit of export-oriented development policies in most Asian and Eastern European countries,[147][148] China has pursued an infrastructure-based development strategy, which has resulted in engineering and construction expertise and a wide range of modern reference projects from which to draw, including roads, bridges, tunnels, and high-speed rail projects.[149] Collectively, many of China's projects are called "mega-infrastructure".

Members of the World Pensions Council (WPC), a non-profit policy research organization, have argued the Belt and Road initiative constitutes a natural extension of the infrastructure-driven economic development framework that has sustained the rapid economic growth of China since the adoption of the Chinese economic reform under chairman Deng Xiaoping,[150] which could eventually reshape the Eurasian economic continuum, and, more generally, the international economic order.[151][152]

Between 2014 and 2016, China's total trade volume in the countries along the Belt and Road exceeded $3 trillion, created $1.1 billion revenues and 180,000 jobs for the countries involved.[153] However, partnering countries worry whether the large debt burden on China to promote the Initiative will make China's pledges declaratory.[154]

Accusations of neocolonialism

There has been concern over the project being a form of neocolonialism. Some Western governments have accused the Belt and Road Initiative of being neocolonial due to what they allege as China practice of debt trap diplomacy to fund the initiative's infrastructure projects.[155]

Swaine (2019) describes such accusations as concerns grossly inflated and oversold, attributing repayment problems in individual cases to reckless and inexperienced practices as opposed to premeditation on the part of Chinese investment.[156] The Chinese government characterizes claims of neocolonialism or debt-trap diplomacy as manipulations to sow mistrust about China's intentions.[157] China contends that the initiative has provided markets for commodities, improved prices of resources and thereby reduced inequalities in exchange, improved infrastructure, created employment, stimulated industrialization, and expanded technology transfer, thereby benefiting host countries.[158] Blanchard (2018) argues that the potential scope of the benefits may not be fully recognized and the negatives exaggerated, noting that critics are concerned with disparaging Chinese investments and suggesting that they should shift their focus to empowering host countries instead.[158] Poghosyan (2018) states that some Chinese experts claim that such Western perceptions of the Belt and Road Initiative are misconstrued due to Western conceptions of development as seen through their own lens of exploitation of others for resources—as exemplified by western European colonialism—instead of through Chinese conceptions of development.[159] Set to differentiate from the coercive nature as was characterized by Western colonialism, as stated by Xing (2017), China's strategic paradigm for the Belt and Road Initiative involves the active participation and cooperation of partner countries.[160]

In 2018, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad cancelled China-funded projects and warns "there is a new version of Colonialism happening",[113] which he later clarified as not being about China and its Belt and Road Initiative in an interview with the BBC HARDtalk.[161][162] Government officials in India have repeatedly objected to China's Belt and Road Initiative, specifically because they believe the "China–Pakistan Economic Corridor" (CPEC) project ignores New Delhi's essential concerns on sovereignty and territorial integrity.[163]

Ecological Issues

The Swiss group Zoï has identified six areas that need to be given careful attention as BRI projects continue to expand in order to prevent long-term ecological damage. They are: Mining practices to be effectively monitored, efforts to move energy production away from coal to renewable alternatives, infrastructure projects to consider and plan in ways to reduce contributions to climate change (I.e. promoting sustainable land use, shortening travel times and distances, and greater fuel efficiency), protecting the biodiversity of project areas, infrastructure projects to calculate ecological affects into the plans, and care needs to be taken not disrupt traditional lifestyles, “local ethnic and indigenous groups.”[164]

The ecological concerns are problematic for many BRI opponents. Many examples are available. “Chinese-backed hydropower projects along the Mekong River – which spans Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam – have seen dams cause river flow changes and block fish migration, leading to a loss of livelihood for communities there which live-off the river.” [165]

Deforestation in areas such as the Pan Borneo Highway – which spans Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei – also causes landslides, floods and other disaster mitigation concerns.[165] Coal-fired power stations, such as Emba Hunutlu power station in Turkey, are being built; thus increasing greenhouse gas emissions and global warming.[166] Glacier melting as a result of excess greenhouse gas emissions, endangered species preservation, desertification and soil erosion as a result of overgrazing and over farming, mining practices, water use management, air and water pollution as a result of poorly planned infrastructure projects are some of the ongoing concerns as they relate to Central Asian nations. [164]

Motivation

Practically, developing infrastructural ties with its neighboring countries will reduce physical and regulatory barriers to trade by aligning standards.[167] China is also using the Belt and Road Initiative to address excess capacity in its industrial sectors, in the hopes that whole production facilities may eventually be migrated out of China into BRI countries.[168]

A report from Fitch Ratings suggests that China's plan to build ports, roads, railways, and other forms of infrastructure in under-developed Eurasia and Africa is out of political motivation rather than real demand for infrastructure. The Fitch report also doubts Chinese banks' ability to control risks, as they do not have a good record of allocating resources efficiently at home, which may lead to new asset-quality problems for Chinese banks that most of funding is likely to come from.[169]

The Belt and Road Initiative is believed by some analysts to be a way to extend Chinese influence at the expense of the US, in order to fight for regional leadership in Asia.[170][171] Some geopolitical analysts have couched the Belt and Road Initiative in the context of Halford Mackinder's heartland theory.[172][173][174] Scholars have noted that official PRC media attempts to mask any strategic dimensions of the Belt and Road Initiative as a motivation.[175] China has already invested billions of dollars in several South Asian countries like Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan to improve their basic infrastructure, with implications for China's trade regime as well as its military influence. China has emerged as one of the fastest-growing sources of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into India – it was the 17th largest in 2016, up from the 28th rank in 2014 and 35th in 2011, according to India's official ranking of FDI inflows.

An analysis by the Jamestown Foundation suggests that the BRI also serves Xi Jinping's intention to bring about "top-level design" of economic development, whereby several infrastructure-focused state-controlled firms are provided with profitable business opportunities in order to maintain high GDP growth.[176] Through the requirement that provincial-level companies have to apply for loans provided by the Party-state to participate in regional BRI projects, Beijing has also been able to take more effective control over China's regions and reduce "centrifugal forces".[176] Others have suggested that the BRI is also an attempt to escape the middle income trap.[177]

Another aspect of Beijing's motivations for BRI is the initiative's internal state-building and stabilisation benefits for its vast inland western regions such as Xinjiang and Yunnan. Academic Hong Yu argues that Beijing's motivations also lie in developing these less developed regions, with increased flows of international trade facilitating closer economic integration with China's inland core.[178] Beijing may also be motivated by BRI's potential to subdue China's Uyghur population. Harry Roberts suggests that the Communist Party is effectively attempting to assimilate China's Uyghur community by using economic opportunities to increase integration between Han settlers and the native population.[179]

Reactions over the world

Supporters of the project

Russia

Moscow has been an early partner of China in the New Silk Roads project. President Putin and President Xi have met several times in the last decade and have already agreed on developments which will be of mutual benefit. In March 2015, Russia's First Deputy Prime Minister Shuvalov asserted that "Russia should not view the Silk Road Economic Belt as a threat to its traditional, regional sphere of influence […] but as an opportunity for the Eurasian Economic Union”. Russia and China now have altogether 150 common projects for Eurasian Union and China. These projects, some under the "Polar Silk Road"[180] plan, include gas transmission system, gas refinery plants, manufacturing of vehicles, heavy industries, and new types of services. Not only that, China Development Bank loaned Russia the equivalent of more than 9.6 billion U.S. dollars.[181] An additional proof both countries are growing into a strong partnership is that in official report titled "The Belt and Road Initiative: Progress, Contributions, and Prospects" Russia was mentioned 18 times, the most out of all countries except China.[182]

Countries in Northern and Central Eurasia, including its largest economies, Russia and Kazakhstan, were among early believers[183] in the value of the Belt and Road Initiative. These countries increasingly embraced various aspects of the BRI, most importantly additional investment and rising volumes of trans-Eurasian сontainer transit from 1,300 in 2010 to 340,000 TEU in 2018[184].

Asia

One of China's claimed official priority is to benefit its neighbors before everyone else. During the second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation which was held in May 2019, Xi Jinping reaffirmed his will to promote regional trade whether it was with President Vorachith of Laos[185] or Prime Minister Lee of Singapore[186] and that, for the benefit of all the parties. This goes in line with the joint effort decided in November 2015 to move Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)-China relations to a higher level of economic cooperation in areas such as Agriculture, IT, Transport, Communications, etc.[187]

Singapore is already a rich, fully developed economy with global interests, and does not need massive external financing or technical assistance for domestic infrastructure building. Nevertheless it has repeatedly endorsed the Belt-and-Road Initiative and cooperated in related projects. The motivation is a quest for global relevance, and the strengthening of economic ties with BRI recipients. Furthermore there is a strategic defensive factor: making sure the China is not the single dominant factor in Asian economics.[188]

Although the Philippines historically has been closely tied to the United States, China has sought its support for the BRI in terms of the quest for dominance in the South China Sea. The Chinese strategy has largely been successful, as the Philippines has adjusted its policy and in favor of Chinese maritime expansion in the South China Sea. Philippines President Rodrigo Roa Duterte has reversed his predecessor's policy of resisting Chinese expansion. He calculates that this will be the economically more beneficial route, expecting a sort of revival of old maritime silk route, and will support his plans for massive infrastructure expansion.[189]

Arab countries

In April 2019 and during the second Arab Forum on Reform and Development, China engaged in an array of partnerships called "Build the Belt and Road, Share Development and Prosperity" with 18 Arab countries. The amount of trade between the two entities has grown almost ten-fold over the last 10 years. That is because China does not see the Middle East as their 'petrol station' anymore. Many further areas of commerce are being involved nowadays; ports in Oman, factories in Algeria, skyscrapers in Egypt's new capital, etc. China is interested in providing financial security to those countries, who after many Arab wars and American interventions, live off the U.S support. On the one hand, Arab countries gain independence and on the other, China opens the door of a colossal market. As the president of Lebanon Michel Aoun stated, "We regard China as a good friend and are willing to further consolidate the relationship with China. We would like to draw the experience from China’s reform and development so as to benefit our people and seek our opportunities for development".[190] An additional advantage on China's part is that it plays a neutral role on the level of diplomacy. China is not interested in intervening between Saudi Arabia and Iran's conflict for instance. Therefore, it succeeds in trading with countries which are enemies.[191]

Africa

Attending the second Belt and Road Forum, former president of the world bank and current president of the UNECA Vera Songwe said: "This (BRI) is probably one of the biggest growths and development initiatives that we have in the world". The statement well sums up the general stand of African countries. Just like Arab countries, they see the BRI as a tremendous opportunity for independence from the foreign aid and influence. More than half the continent has already signed partnerships with the Middle Kingdom. Lu Kang, spokesman for China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs recently declared: "We will advance bilateral cooperation in areas including industries, infrastructure, trade and investment, improve the living standards of African people, bring more development dividends to African countries, and deliver more benefits to people in China and Africa". Not only that, he continued saying: "The two sides have already launched many important cooperation projects and achieved early harvests".[192]

Europe

Greece, Croatia and 14 other eastern Europe countries are already dealing with China within the frame of the BRI. While most of them still suffer the aftereffect of the 2008 economic crisis, proponents argue that China's approach creates a new range of opportunities. In March 2019, Italy was the first member of the Group of Seven nations to join the Chinese Initiative. The new partners signed a 2.5 billion euros “Memorandum of Understanding” across an array of sectors such as transport, logistics and port infrastructure to strengthen financial cooperation.[193] The Italian PM immediately affirmed his trust toward China declaring: "Cooperation is bigger than competition between China and Europe". Italian PM Giuseppe Conte's decision was followed soon thereafter by neighboring countries Luxembourg and Switzerland. A few weeks later, China won another victory by consolidating billions of dollars' worth of infrastructure deals with the 16+1 Nations, which changed its name to the 17+1 group, as it saw Greece join the alliance as well. Poland's President Andrzej Duda stated that "Polish companies will benefit hugely" from China's Belt and Road Initiative.[194] Duda and Xi signed a declaration on strategic partnership in which they reiterated that Poland and China viewed each other as long-term strategic partners.[195]

Opponents to the project

Australia, Japan, India and the US 'Indo-Pacific Vision'

Japan, India and Australia joined forces to create an alternative to the Belt and Road creating the “Blue Dot Network”. In reality, very few details are known about the project although it was initiated in 2016. By and large, the cooperation highlighted two topics: securing the Pacific Ocean and guaranteeing free trade in the region.

By 2019, the United States joined the initiative thus renaming the alliance into the "Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy" (FOIP). President Donald Trump has begun translating the U.S. Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy (FOIP) into more concrete initiatives across what officials have articulated as three pillars – security, economics, and governance. This can be seen as a direct counterattack against China which expands its military and whose communist roots are viewed by some as antagonistic to the idea of free trade.[196]

World Pensions Council director M. Nicolas J. Firzli has argued that the United States and its allies will strive to court large private sector asset owners such as pension funds, inviting them to play an increasingly important geo-economic part across the Asia Pacific area, alongside US and other state actors:

Even the self-absorbed, thrifty 'America first' policy makers in the White House eventually realized they couldn’t ignore these fateful geo-economic developments. In November 2018, vice-president Mike Pence travelled to Asia to promote President Trump's 'Indo-Pacific Vision', an ambitious plan backed by tens of billions of dollars in new loans and credit-enhancement mechanisms to encourage "private investment in regional infrastructure assets", insisting that "business, not bureaucrats will facilitate our efforts". The new great game has just started, and pension investors will be courted assiduously by both Washington and Beijing in the coming years – not a bad position to be in in the 'age of geoeconomics'.[197]

At the beginning of June 2019, there has been a redefinition of the general definitions of "free" and "open" into four specific principles – respect for sovereignty and independence; peaceful resolution of disputes; free, fair, and reciprocal trade; and adherence to international rules and norms.[198] Leaders committed that the United States and India should intensify their economic cooperation to "make their nations stronger and their citizens more prosperous".

Vietnam historically has been at odds with China for a thousand years, and generally opposes the South China Sea expansion. It in recent decades has been on close terms with the United States and Japan. However, China is so big and so close, that Vietnam has been indecisive about support or opposition to BR.[199]

The response of South Korea has been to evade Chinese overtures and instead try to develop the "Eurasia Initiative" (EAI) as its own vision for an East-West connection. In calling for a revival of the ancient Silk Road, the main goal of President Park Geun-hye was to encourage a flow of economic, political, and social interaction from Europe though the Korean Peninsula. Her successor, President Moon Jae-in announced his own foreign policy initiative, the |New Southern Policy" (NSP), which seeks to strengthen relations with Southeast Asia. Both EAI and NSP were proposed to strengthen the long-term goal of peace with North Korea. These policies are the product of the South Korean vulnerability to great power competition. It is trying to build economic ties with smaller powers so as to increase Seoul's foreign policy leverage as a middle power.[200]

European Union

Recently, Italy and Greece have been the first major powers to join the Belt and Road Initiative, stressing the urgency for the EU to clarify its positions towards China international policies. Indeed, whereas Italy's Deputy Prime Minister Luigi Di Maio told that the accord was "nothing to worry about", French and German leaders are less optimistic. President Macron even said in Brussels that "the time of European naïveté is ended". "For many years", he added, "we had an uncoordinated approach and China took advantage of our divisions."[201]

At the end of March 2019, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker joined for talks with Xi in Paris in company of President Macron. There, Macron exhorted China to "respect the unity of the European Union and the values it carries in the world". Juncker on his end stressed that European companies should find "the same degree of openness in the China market as Chinese ones find in Europe." In the same vein, Merkel declared that the BRI "must lead to a certain reciprocity, and we are still wrangling over that bit." In January 2019 Macron said: "the ancient Silk Roads were never just Chinese … New roads cannot go just one way."[193]

In late December 2018 Germany tightened its policies around foreign trade, increasing their ability to restrict certain direct or indirect acquisitions of shares in German companies on based on national security.[202]

As a consequence to the growing criticism of the Belt and Road Initiative and the lacking transparency, European Commission Chief Jean-Claude Juncker and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe signed an infrastructure agreement in Brussels on the 27th of September 2019. This pact between Europe and Japan is intended to counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative and link Europe and Asia to coordinate infrastructure, transport and digital projects.[203][204]

Furthermore, the EU is one of the biggest development donors in the world and many African economies, which are being observed as a backdoor for EU investments and partnerships, have been neglected in recent decades and therefore, the EU fears being outflanked by China and its major investments in the infrastructure in the African region.[205]

With regard to the already declining cohesion within the EU, EU diplomats are fearing a further destabilization of the region due to varying China attitudes and policies among the countries and the increasing geopolitical power of China, especially in the South-Eastern countries that are running into big debt.[206]

European economists and ambassadors are also rising serious concerns about the impacts of the New Silk Road on the balance of power in International Trade and fear a shift towards China in favor of its highly subsidized and state-owned companies.[207] Moreover, the Chinese rise regarding economic success and digitalization and the major comparative advantages the Chinese companies could establish in this field in recent decades are going to challenge European companies in particular and require reforms within the EU in order to ensure the competitiveness of European companies.[208]

Even though China stated that its massive infrastructural project is going to benefit every country that is being affected, there is apprehension across European countries that the Initiative is going to undermine European environmental and social standards and counter the EU’s agenda for liberalizing trade.[209]

Think tank

A French think tank, focused on the study of the New Silk Roads, was launched in 2018. It is described as pro–Belt and Road Initiative and pro-China.[210]

See also

- Asian Highway Network

- Eurasian Land Bridge

- Foreign policy of China

- Indo-Pacific

- List of the largest trading partners of China

- Trans-Asian Railway

- International North–South Transport Corridor

- Asia-Africa Growth Corridor

References

- "我委等有关部门规范"一带一路"倡议英文译法". www.ndrc.gov.cn (in Chinese). National Development and Reform Commission. 11 May 2019. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- "Belt and Road Initiative". World Bank. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Overview – Belt and Road Initiative Forum 2019". Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Kuo, Lily; Kommenda, Niko. "What is China's Belt and Road Initiative?". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- "Wayback Machine" (PDF). 13 July 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "BRI Instead of OBOR – China Edits the English Name of its Most Ambitious International Project". liia.lv. 28 July 2016. Archived from the original on 6 February 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- 王毅:着力打造西部陆海新通道 推动高质量共建"一带一路"-新华网. www.xinhuanet.com (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "China unveils action plan on Belt and Road Initiative". Gov.cn. Xinhua. 28 March 2015. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

-

Compare:

Chohan, Usman W. (7 July 2017). "What Is One Belt One Road? A Surplus Recycling Mechanism Approach". SSRN 2997650.

It has been lauded as a visionary project among key participants such as China and Pakistan, but has received a critical reaction, arguably a poorly thought out one, in nonparticipant countries such as the United States and India (see various discussions in Ferdinand 2016, Kennedy and Parker 2015, Godement and Kratz, 2015, Li 2015, Rolland 2015, Swaine 2015).

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) -

Compare: "Getting lost in 'One Belt, One Road'". Hong Kong Economic Journal. 12 April 2016. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

Simply put, China is trying to buy friendship and political influence by investing massive amounts of money on infrastructure in countries along the 'One Belt, One Road'.

- "CrowdReviews Partnered with Strategic Marketing & Exhibitions to Announce: One Belt, One Road Forum". PR.com. 25 March 2019. Archived from the original on 30 April 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- "Chronology of China's Belt and Road Initiative". China's State Council. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- Qian, Gang (钱钢) (23 February 2017). 钱钢语象报告:党媒关键词温度测试 (in Chinese). WeChat.Archived 27 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Rolland, Nadège (5 March 2019). "The Geo-Economic Challenge of China's Belt and Road Initiative". War on the Rocks. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- "News—Zhejiang Uniview Technologies Co., Ltd". en.uniview.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- General Office of Leading Group of Advancing the Building of the Belt and Road Initiative (2016). "Belt and Road in Big Data 2016". Beijing: the Commercial Press.

- "What to Know About China's Belt and Road Initiative Summit". Time. Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Griffiths, James. "Just what is this One Belt, One Road thing anyway?". CNN. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- 3=World Pensions Council (WPC) Firzli, Nicolas (February 2017). "World Pensions Council: Pension Investment in Infrastructure Debt: A New Source of Capital". World Bank blog. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- 3=World Pensions Council (WPC) Firzli, M. Nicolas J. (October 2015). "China's Asian Infrastructure Bank and the 'New Great Game'". Analyse Financière. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- 一带一路领导班子"一正四副"名单首曝光. Ifeng (in Chinese). 5 April 2015. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015.

- Joshi, Prateek (2016). "The Chinese Silk Road in South & Southeast Asia: Enter "Counter Geopolitics"". IndraStra Global (Data Set) (3): 4. doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.3084253.

- "Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road". National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), People's Republic of China. 28 March 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- Ramasamy, Bala; Yeung, Matthew; Utoktham, Chorthip; Duval, Yann (November 2017). "Trade and trade facilitation along the Belt and Road Initiative corridors" (PDF). ARTNeT Working Paper Series, Bangkok, ESCAP (172). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- "Getting lost in 'One Belt, One Road'". 12 April 2016. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- Our bulldozers, our rules Archived 23 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Economist, 2 July 2016

- "China to step up Russian debt financing". China Daily. 9 May 2015. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- "Silk Road Economic Belt_China.org.cn". china.org.cn. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- "Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Belt and Road". Xinhua. 29 March 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- "CPEC investment pushed from $55b to $62b – The Express Tribune". 12 April 2017. Archived from the original on 15 May 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- Hussain, Tom (19 April 2015). "China's Xi in Pakistan to cement huge infrastructure projects, submarine sales". McClatchy News. Islamabad: mcclatchydc. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- Kiani, Khaleeq (30 September 2016). "With a new Chinese loan, CPEC is now worth $57bn". Dawn. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- "CPEC: The devil is not in the details". 23 November 2016. Archived from the original on 14 May 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- "Economic corridor: Chinese official sets record straight". The Express Tribune. 2 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- Ramachandran, Sudha (16 November 2016). "CPEC takes a step forward as violence surges in Balochistan". www.atimes.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- Based on 《一帶一路規劃藍圖》 in Nanfang Daily

- "Xi Jinping Calls For Regional Cooperation Via New Silk Road". The Astana Times. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- Henderson, Isaiah M. (4 February 2019). "The Chinese Empire Rises: BRI Emerges as Tool of Conquest and Challenge to the U.S. Order". The California Review. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Integrating #Kazakhstan Nurly Zhol, China's Silk Road economic belt will benefit all, officials say". EUReporter. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- "Sri Lanka Supports China's Initiative of a 21st Century Maritime Silk Route". Archived from the original on 11 May 2015.

- Shannon Tiezzi, The Diplomat. "China Pushes 'Maritime Silk Road' in South, Southeast Asia". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- "Reflections on Maritime Partnership: Building the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road". Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- "Xi in call for building of new 'maritime silk road'". China Daily. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- Suokas, J., China, Russia to build ‘Ice Silk Road’ along Northern Sea Route Archived 18 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine, GB Times, published 6 July 2017, accessed 10 March 2019

- Henderson, Isaiah M. (18 July 2019). "Cold Ambition: The New Geopolitical Faultline". The California Review. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "The XVI International conference "Development of a Shelf Russian Federation and CIS-2019" will open on May 17, 2019 in Moscow". news.myseldon.com. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- Pattinson, Victor (22 May 2019). "Russia and China started global infrastructure project Ice Silk Road". Medium. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Fairley, Peter (21 February 2019). "China's Ambitious Plan to Build the World's Biggest Supergrid". IEEE Spectrum: Technology, Engineering, and Science News. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- "China drops BCIM from BRI projects' list". Business Standard India. 28 April 2019 – via Business Standard.

- 已同中國簽訂共建一帶一路合作文件的國家一覽. BRI Official Website. 12 April 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- "B&R interconnection witnesses great breakthroughs in 5-year development-Belt and Road Portal". eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- China Global Investment Tracker The BRI's Future in Derek Scissors, "The Belt and Road is Overhyped, Commercially." AEI Paper & Studies (American Enterprise Institute, 2019) online

- "Belt and Road Initiative strikes again… Djibouti risks Chinese takeover with massive loans – US warns". Kaieteur News. 2 September 2018. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- "How tiny African Nation of Djibouti became Linchpin in Belt & Road". 29 April 2019. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "Feature: Chinese construction projects in Egypt's new capital city model for BRI-based cooperation". 18 March 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- "Chinese Company Investing in Ethiopia's Eastern Industrial Zone". CGTN. 15 May 2017. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- "Ethiopia's First Industry Zone to Start Phase-2 Construction Soon". Xinhua Net. 11 June 2018. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Philip Giannecchini, Ian Taylor (2018). "The eastern industrial zone in Ethiopia: Catalyst for development?". Geoforum. 88: 28–35. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.11.003. hdl:10023/18971.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Ethiopia-Djibouti electric railway line opens". BBC News. 5 October 2016. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "Ethiopia-Djibouti Railway Line Modernization". Railway Technology. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "Chinese FM prioritises three areas in development of China – Ethiopia relations". 5 January 2019.

- "Kenya Opens Nairobi-Monbasa Madaraka Express Railway". BBC News. 31 May 2017. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "One Year On: China-built Railway Revitalizes Regional Trade in Kenya". Xinhua Net. 1 June 2018. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "Nigeria's first standard gauge railway marks 900 days of safe operation-Belt and Road Portal". eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- "China launches digital TV project for 1,000 Nigerian villages-Belt and Road Portal". eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- "Spotlight: Sudan expects to play bigger role in Belt and Road Initiative -- analysts - Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- "All aboard the China-to-London freight train". BBC News. 18 January 2017. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "The New Silk Road: China Launches Beijing-London Freight Train Route". Jonathan Webb. 3 January 2017. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "China–European Freight Trains Make 10,000 Trips". Xinhua Net. 27 August 2018. Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "China–Europe Freight Train Service Extended Southwards to Vietnam". Xinhua Net. 18 March 2018. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- Dong, Zhicheng (董志成). "Poland looking to bolster trade with China under BRI - Chinadaily.com.cn". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 4 November 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- "Poland and China sign universal strategic partnership pact". Radio Poland. 20 June 2016.

- Xinhua. "Greece to strengthen cooperation with China under Belt and Road". gbtimes.com. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- "China and Greece are "natural partners" in Belt & Road Initiative - Belt & Road News". 12 November 2019.

- "Portugal signs agreement with China on Belt and Road Initiative". South China Morning Post. 5 December 2018. Archived from the original on 6 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- Cristiani, Dario (24 April 2019). "Italy Joins the Belt and Road Initiative: Context, Interests, and Drivers". Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "Italy becomes first G7 nation to join China's 'Belt & Road Initiative". theindependent.in. 24 March 2019. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ""What Does the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Mean for Austria and the Region of Central East and Southeast Europe (CESEE)?" (Part 2)". imfino.com. Archived from the original on 4 November 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- "Are you a robot?". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 10 June 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- Stephens, Thomas. "Swiss president strengthens economic ties with China - SWI". Swissinfo.ch. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- "It's time for Armenia to become part of new Silk Road – Armenian President meets with Chinese delegation". armenpress.am. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- "Georgian Infrastructure Minister participating at Belt and Road Forum in China". Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- "China and Russia forge stronger Eurasian economic ties as Vladimir Putin gets behind Xi Jinping's belt and road plan in face of US hostility | South China Morning Post". Scmp.com. 26 April 2019. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- "China's leader: One Belt One Road and EAEU synergy to boost region's developmentl cooperation". TASS. 7 June 2019. Archived from the original on 10 June 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- 中华人民共和国和俄罗斯联邦关于发展新时代全面战略协作伙伴关系的联合声明(全文) (in Chinese). Xinhua. 6 June 2019. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "Interview: China–Belarus Industrial Park propels Belarusian economy". Xinhua Net. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- "China–Belarus Industrial Park makes breakthrough in attracting investors". China Daily. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- Vakulchuk, Roman and Indra Overland (2019) “China’s Belt and Road Initiative through the Lens of Central Asia”, in Fanny M. Cheung and Ying-yi Hong (eds) Regional Connection under the Belt and Road Initiative. The Prospects for Economic and Financial Cooperation. London: Routledge, pp. 115–133.

- "BRI in Central Asia: Overview of Chinese Projects" (PDF).

- "Kazakhstan has turned into 'competitive transit hub', Nazarbayev tells Belt and Road forum". astanatimes.com. 27 April 2019. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- "Belt and Road Initiative in Central Asia and the Caucasus". 11 March 2019.

- Mogilevskii, Roman (2019). "Kyrgyzstan and the Belt and Road Initiative" (PDF). University of Central Asia Working Papers. #50: 26.

- Qoraboyev, Ikboljon (April 2018). "The Belt and Road Initiative and Uzbekistan's New Strategy of Development: Sustainability of mutual relevance and positive dynamics". Research Gate.

- "BRI cooperation boosts China-Uzbekistan partnership". China.org.cn. 31 October 2019.

- Reynolds, Sam (23 August 2018). "For Tajikistan, the Belt and Road Is Paved with Good Intentions". The National Interest.

- Bhutia, Sam (2 October 2019). "Who wins in China's great Central Asia spending spree?". Eurasianet.

- Choganov, Kerven (16 December 2019). "Turkmenistan's strategic corridors". One Belt One Road Europe.

- "Lawmakers should stop CY Leung from expanding govt power". EJ Insight. 16 November 2015. Archived from the original on 23 February 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- "We get it, CY ... One Belt, One Road gets record-breaking 48 mentions in policy address". South China Morning Post. 13 January 2016.

- 【政情】被「洗版」特首辦官員調職瑞士 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 17 January 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- "2016 Policy Address: too macro while too micro". EJ Insight. 15 January 2016. Archived from the original on 16 January 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- "Construction of Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway in full swing in Indonesia". Xinhua Net. Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- "Jakarta-Bandung railway project won't meet target, Minister". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- "China–Laos railway completes first continuous beam block construction on Mekong River". Xinhua Net. 22 September 2018. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.