Uyghurs

The Uyghurs (/ˈwiːɡʊərz/,[19] /uːiˈɡʊərz/; Uyghur: ئۇيغۇرلار , уйғурлар, IPA: [ujɣurˈlɑr]; simplified Chinese: 维吾尔; traditional Chinese: 維吾爾; pinyin: Wéiwú'ěr, [wěiǔàɚ]),[20][21] alternately Uygurs, Uighurs[22] or Uigurs, are a Turkic minority ethnic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the general region of Central and East Asia. The Uyghurs are recognized as native[note 1] to the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in Northwest China. They are considered to be one of China's 55 officially recognized ethnic minorities.[23] The Uyghurs are recognized by the Chinese government only as a regional minority within a multicultural nation. The Chinese government rejects the notion of the Uyghurs being an indigenous group.[24]

ئۇيغۇر Uyghur · Уйғур · 维吾尔 | |

|---|---|

Uyghur man, Kashgar | |

| Total population | |

| c. 12 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

(mainly in Xinjiang) | 11,303,355[2][3][4] |

| 223,100 (2009) (Uyghurs in Kazakhstan)[5][6] | |

| 55,220 (2008)[7][8] | |

| 48,543 (2009) (Uyghurs in Kyrgyzstan)[9] | |

| ~50,000 (2013) (Saudi Labor Ministry)[10] | |

| ~10,000 (2018)[11] | |

| 5,000–10,000[12] | |

| ~1,000 families (2010) (Uyghurs in Pakistan)[13] | |

| 3,696 (2010)[14] | |

| ~1,555 (2016)[15] | |

| 1,000+ (Uyghur Americans)[16] | |

| ~1,000 (2012)[17] | |

| 197 (2001)[18] | |

| Languages | |

| Predominantly Uyghur Also Russian (in Central Asia), Mandarin and Äynu (in China) | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Turkic peoples | |

The Uyghurs have traditionally inhabited a series of oases scattered across the Taklamakan Desert within the Tarim Basin, a territory that has historically been controlled by many civilizations including China, the Mongols, the Tibetans and various Turkic polities. The Uyghurs gradually started to become Islamized in the 10th century and most Uyghurs identified as Muslims by the 16th century. Islam has since played an important role in Uyghur culture and identity.

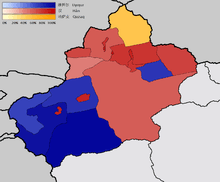

An estimated 80% of Xinjiang's Uyghurs still live in the Tarim Basin.[25] The rest of Xinjiang's Uyghurs mostly live in Ürümqi, the capital city of Xinjiang UAR, which is located in the historical region of Dzungaria. The largest community of Uyghurs living in another region of China are the Uyghurs living in Taoyuan County, in North-Central Hunan.[26] Significant diasporic communities of Uyghurs exist in the Central Asian countries of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.[27] Smaller communities live in Canada, Germany, Belgium, Norway, Sweden, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Afghanistan, Australia, the United States and the Netherlands.

Since 2015, it has been estimated that over a million Uyghurs (approximately 1 in 10[28]) have been detained in Xinjiang re-education camps.[29][30][31][32][33][34] The camps were established under General Secretary Xi Jinping’s administration with the main goal of ensuring adherence to national ideology.[35]

Name

In the Uyghur language, the ethnonym is written ئۇيغۇر in Arabic script, Уйгур in Russian, Уйғур in Uyghur Cyrillic and Uyghur or Uygur (as the standard romanisation in Chinese GB 3304-1991) in Latin;[36] they are all pronounced as [ʔʊjˈʁʊː].[37][38] In Chinese, this is transcribed into characters as 维吾尔 / 維吾爾, which is romanized in pinyin as Wéiwú'ěr.

In English, the name is officially spelled "Uyghur" by the Xinjiang government[39] but also appears as "Uighur",[19] "Uigur"[19] and "Uygur". (These reflect the various Cyrillic spellings Уиғур, Уигур and Уйгур.) The name is usually pronounced in English as /ˈwiːɡʊər/,[19] although some Uyghurs and Uyghur scholars advocate for using the closer pronunciation /uːiˈɡʊər/ instead.[20][21]

The original meaning of the term is unclear. Old Turkic inscriptions record a word uyɣur[40] (𐰺𐰍𐰖𐰆),[41] transcribed into Tang annals as 回纥 / 回紇 (Mandarin: Huíhé, but probably *[ɣuɒiɣət] in Middle Chinese).[42] It was used as the name of one of the Turkic polities formed in the interim between the First and Second Göktürk Khaganates (AD 630-684).[43] The Old History of the Five Dynasties records in 788 or 809, the Chinese acceded to a Uyghur request, and emended their transcription to 回鹘 / 回鶻 (Mandarin: Huíhú, but [ɣuɒiɣuət] in Middle Chinese).[44] Modern etymological explanations for the name "Uyghur" range from derivation from the verb "follow, accommodate oneself""[19] and adjective "non-rebellious" (i.e., from Turkic uy/uð-) to the verb meaning "wake, rouse, or stir" (i.e., from Turkic oðğur-). None of these is thought to be satisfactory because the sound shift of /ð/ and /ḏ/ to /j/ does not appear to be in place by this time.[44] The etymology therefore cannot be conclusively determined, and its referent is also difficult to fix. The "Huihe" and "Huihu" seem to be a political rather than a tribal designation,[45] or it be may be one group among several others collectively known as the Toquz Oghuz.[46] The name fell out of use in the 15th century, but was reintroduced in the early 20th century[37][38] by the Soviet Bolsheviks to replace the previous terms "Turk" and "Turki".[47][note 2] The name is presently used to refer to the settled Turkic urban dwellers and farmers of the Tarim Basin who follow traditional Central Asian sedentary practices, distinguishable from the nomadic Turkic populations in Central Asia.

The Uyghurs also appear in Chinese records under other names. The earliest record of a Uyghur tribe appears in accounts from the Northern Wei (4th–6th century A.D.). They are described as the 高车 / 高車 (lit. "High Carts"), read as Gāochē in Mandarin Chinese but originally with the reconstructed Middle Chinese pronunciation *[kɑutɕʰĭa]. This in turn has been connected to the Uyghur Qangqil (قاڭقىل or Қаңқил). They were later known as the Tiele (铁勒 / 鐵勒, Tiělè).[49]

Identity

Throughout its history, the term Uyghur has an increasingly expansive definition. Initially signifying only a small coalition of Tiele tribes in Northern China, Mongolia, and the Altai Mountains, it later denoted citizenship in the Uyghur Khaganate. Finally, it was expanded into an ethnicity whose ancestry originates with the fall of the Uyghur Khaganate in the year 842, causing Uyghur migration from Mongolia into the Tarim Basin.

This migration assimilated and replaced the various Indo-European speakers of the region to create a distinct identity because the language and culture of the Turkic migrants eventually supplanted the original Indo-European influences. This fluid definition of Uyghur and the diverse ancestry of modern Uyghurs create confusion as to what constitutes true Uyghur ethnography and ethnogenesis. Contemporary-scholars consider modern Uyghurs to be the descendants of a number of peoples, including the ancient Uyghurs of Mongolia migrating into the Tarim Basin after the fall of the Uyghur Khaganate, Iranic Saka tribes, and other Indo-European peoples inhabiting the Tarim Basin before the arrival of the Turkic Uyghurs.[50] 37% or 4.1 million Uyghurs in China have European ancestors.[51][52] They represent 0.31% of the total population of China.

DNA analyses indicate the peoples of central Asia such as the Uyghurs are all mixed "Caucasian" and East Asian.[23] Uyghur activists identify with the Tarim mummies, remains of an ancient people inhabiting the region, but research into the genetics of ancient Tarim mummies and their links with modern Uyghurs remains problematic, both to Chinese government officials concerned with ethnic separatism, and to Uyghur activists concerned the research could affect their indigenous claim.[53][54]

Origin of the modern ethnic concept

The Uighurs are the people whom old Russian travellers called Sart (a name which they used for sedentary, Turkish-speaking Central Asians in general), while Western travellers called them Turki, in recognition of their language. The Chinese used to call them Ch'an-t'ou ('Turbaned Heads') but this term has been dropped, being considered derogatory, and the Chinese, using their own pronunciation, now called them Weiwuerh. As a matter of fact there was for centuries no 'national' name for them; people identified themselves with the oasis they came from, like Kashgar or Turfan.

— Owen Lattimore, "Return to China's Northern Frontier." The Geographical Journal, Vol. 139, No. 2, June 1973[55]

The term "Uyghur" was not used to refer to a specific existing-ethnicity in the 19th century; it referred to 'ancient people'. A late 19th-century encyclopedia titled The cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia said "the Uigur are the most ancient of Turkish tribes, and formerly inhabited a part of Chinese Tartary (Xinjiang), now occupied by a mixed population of Turk, Mongol, and Kalmuck".[56] Before 1921/1934, Western writers called the Turkic-speaking Muslims of the oases "Turki", and the Turkic Muslims who had migrated from the Tarim Basin to Ili, Ürümqi and Dzungaria in the northern portion of Xinjiang during the Qing dynasty were known as "Taranchi" meaning "farmer". The Russians and other foreigners referred to them as "Sart",[57] "Turk", or "Turki".[58][note 2] In the early 20th century, they identified by different names to different peoples and in response to different inquiries: they called themselves Sarts in front of Kyrgyz and Kazakhs, while they called themselves "Chantou" if asked about their identity after first identifying as a Muslim.[59][60] The term "Chantou" (纏頭; Ch'an-t'ou, meaning "Rag head" or "Turban Head") was used to refer to the Turkic Muslims of Xinjiang,[61][62] including by Hui (Tungan) people.[63] These groups of peoples often identify themselves by their originating oasis instead of an ethnicity;[64] for example those from Kashgar may refer to themselves as Kashgarliq or Kashgari, while those from Hotan identity themselves as "Hotani".[60][65] Other Central Asians once called all the inhabitants of Xinjiang's Southern oases Kashgari,[66] a term still used in some Pakistan regions.[67] The Turkic people also used "Musulman", which means "Muslim", to describe themselves.[65][68][69]

Rian Thum explored the concepts of identity among the ancestors of the modern Uyghurs in Altishahr (the native Uyghur name for eastern Turkestan or southern Xinjiang) before the adoption of the name "Uyghur" in the 1930s, referring to them by the name "Altishahri" in his article Modular History: Identity Maintenance before Uyghur Nationalism. Thum indicated that Altishahri Turkis did have a sense that they were a distinctive group separate from the Turkic Andijanis to their west, the nomadic Turkic Kirghiz, the nomadic Mongol Qalmaq, and the Han Chinese Khitay before they became known as Uyghurs. There was no single name used for their identity; various native names Altishahris used for identify were Altishahrlik (Altishahr person), yerlik (local), Turki, and Musulmān (Muslim); the term Musulmān in this situation did not signify religious connotations, because the Altishahris exclude other Muslim peoples like the Kirghiz while identifying themselves as Musulmān.[70][71] Dr. Laura J Newby says the sedentary Altishahri Turkic people considered themselves separate from other Turkic Muslims since at least the 19th century.[72]

The name "Uyghur" reappeared after the Soviet Union took the 9th-century ethnonym from the Uyghur Khaganate, then reapplied it to all non-nomadic Turkic Muslims of Xinjiang.[73] It followed western European orientalists like Julius Klaproth in the 19th century who revived the name and spread the use of the term to local Turkic intellectuals,[74] and a 19th-century proposal from Russian historians that modern-day Uyghurs were descended from the Kingdom of Qocho and Kara-Khanid Khanate formed after the dissolution of the Uyghur Khaganate.[75] Historians generally agree that the adoption of the term "Uyghur" is based on a decision from a 1921 conference in Tashkent, attended by Turkic Muslims from the Tarim Basin (Xinjiang).[73][76][77][78] There, "Uyghur" was chosen by them as the name of their ethnicity, although delegates noted the modern groups referred to as "Uyghur" are distinct from the old Uyghur Khaganate.[57][79] According to Linda Benson, the Soviets and their client Sheng Shicai intended to foster a Uyghur nationality to divide the Muslim population of Xinjiang, whereas the various Turkic Muslim peoples preferred to identify themselves as "Turki", "East Turkestani", or "Muslim".[57]

On the other hand, the ruling regime of China at that time, the Kuomintang, grouped all Muslims, including the Turkic-speaking people of Xinjiang, into the "Hui nationality".[80][81] The Qing dynasty and the Kuomintang generally referred to the sedentary oasis-dwelling Turkic Muslims of Xinjiang as "turban-headed Hui" to differentiate them from other predominantly Muslim ethnicities in China.[57][82][note 3] Foreigners traveling in Xinjiang in the 1930s, like George W. Hunter, Peter Fleming, Ella Maillart, and Sven Hedin, referred to the Turkic Muslims of the region as "Turki" in their books. Use of the term Uyghur was unknown in Xinjiang until 1934. The area governor, Sheng Shicai, came to power, adopting the Soviet ethnographic classification instead of the Kuomintang's, and became the first to promulgate the official use of the term "Uyghur" to describe the Turkic Muslims of Xinjiang.[57][75][84] "Uyghur" replaced "rag-head".[85]

Sheng Shicai's introduction of the "Uighur" name for the Turkic people of Xinjiang was criticized and rejected by Turki intellectuals such as Pan-Turkist Jadids and East Turkestan independence activists Muhammad Amin Bughra (Mehmet Emin) and Masud Sabri. They demanded the names "Türk" or "Türki" be used instead as the ethnonyms for their people. Masud Sabri viewed the Hui people as Muslim Han Chinese and separate from his people,[86] while Bughrain criticized Sheng for his designation of Turkic Muslims into different ethnicities which could sow disunion among Turkic Muslims.[87][88] After the Communist victory, the Communist Party of China under Mao Zedong continued the Soviet classification, using the term "Uyghur" to describe the modern ethnicity.[57]

In current usage, Uyghur refers to settled Turkic speaking urban dwellers and farmers of the Tarim Basin and Ili who follow traditional Central Asian sedentary practices, as distinguished from nomadic Turkic populations in Central Asia. However, the Chinese government agents designate as "Uyghur" certain peoples with significantly divergent histories and ancestries from the main group. These include the Lopliks of Ruoqiang County and the Dolan people, thought to be closer to the Oirat Mongols and the Kyrgyz.[89][90] The use of the term Uyghur led to anachronisms when describing the history of the people.[91] In one of his books, the term Uyghur was deliberately not used by James Millward.[92]

Another ethnicity, the Western Yugur of Gansu, identify themselves as the "Yellow Uyghur" (Sarïq Uyghur).[93] Some scholars say the Yugur's culture, language, and religion are closer to the original-culture of the original Uyghur Karakorum state than is the culture of the modern Uyghur people of Xinjiang.[94] Linguist and ethnographer S. Robert Ramsey argues for inclusion of both the Eastern and Western Yugur and the Salar as sub-groups of the Uyghur based on similar historical roots for the Yugur and on perceived linguistic similarities for the Salar.[95]

"Turkistani" is used as an alternate ethnonym by some Uyghurs.[96] For example, the Uyghur diaspora in Arabia, adopted the identity "Turkistani". Some Uyghurs in Saudi Arabia adopted the Arabic nisba of their home city, such as "Al-Kashgari" from Kashgar. Saudi born Uyghur Hamza Kashgari's family originated from Kashgar.[97][98]

History

The history of the Uyghur people, as with the ethnic origin of the people, is a matter of contention between Uyghur nationalists and the Chinese authority.[99] Uyghur historians viewed the Uyghurs as the original inhabitants of Xinjiang with a long history. Uyghur politician and historian Muhemmed Imin Bughra wrote in his book A History of East Turkestan, stressing the Turkic aspects of his people, that the Turks have a 9000-year history, while historian Turghun Almas incorporated discoveries of Tarim mummies to conclude that Uyghurs have over 6400 years of history,[100] and the World Uyghur Congress claimed a 4,000-year history in East Turkestan.[101] However, the official Chinese view asserts that the Uyghurs in Xinjiang originated from the Tiele tribes and only became the main social and political force in Xinjiang during the ninth century when they migrated to Xinjiang from Mongolia after the collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate, replacing the Han Chinese they claimed were there since the Han Dynasty.[100] Many contemporary Western scholars, however, do not consider the modern Uyghurs to be of direct linear descent from the old Uyghur Khaganate of Mongolia. Rather, they consider them to be descendants of a number of peoples, one of them the ancient Uyghurs.[50][102][103][104]

Early history

Discovery of well-preserved Tarim mummies of a people European in appearance indicates the migration of an Indo-European people into the Tarim area at the beginning of the Bronze Age around 1800 BCE. These people, likely to be of Tocharian origin, were suggested by some to be the Yuezhi mentioned in ancient Chinese texts.[105][106] However, Uyghur activists claimed these mummies to be of Uyghur origin, based partly on a word, which they argued to be Uyghur, found in written scripts associated with these mummies, although other linguists suggest it to be a Sogdian word later absorbed into Uyghur.[107] Later migrations brought peoples from the west and north-west to the Xinjiang region, probably speakers of various Iranian languages such as the Saka tribes. Other people in the region mentioned in ancient Chinese texts include the Dingling as well as the Xiongnu who fought for supremacy in the region against the Chinese for several hundred years. Some Uyghur nationalists also claimed descent from the Xiongnu (according to the Chinese historical text the Book of Wei, the founder of the Uyghurs was descended from a Xiongnu ruler),[44] but the view is contested by modern Chinese scholars.[100]

The Yuezhi were driven away by the Xiongnu, but founded the Kushan Empire, which exerted some influence in the Tarim Basin where Kharosthi texts have been found in Loulan, Niya and Khotan. Loulan and Khotan were some of the many city states that existed in the Xinjiang region during the Han Dynasty, others include Kucha, Turfan, Karasahr and Kashgar. These kingdoms in the Tarim Basin came under the intermittent control of China during the Han and Tang dynasties. During the Tang dynasty, they were conquered and placed under the control of the Protectorate General to Pacify the West, and the Indo-European cultures of these kingdoms never recovered from Tang rule after thousands of their inhabitants were killed during the conquest.[108] The settled population of these cities later merged with incoming Turkic people including the Uyghurs of Uyghur Khaganate to form the modern Uyghurs.

Uyghur Khaganate (8th–9th centuries)

The Uyghurs of the Uyghur Khaganate were part of a Turkic confederation called the Tiele,[109] who lived in the valleys south of Lake Baikal and around the Yenisei River. They overthrew the Turkic Khaganate and established the Uyghur Khaganate.

The Uyghur Khaganate stretched from the Caspian Sea to Manchuria and lasted from 744 to 840.[50] It was administered from the imperial capital Ordu-Baliq, one of the biggest ancient cities built in Mongolia. In 840, following a famine and civil war, the Uyghur Khaganate was overrun by the Yenisei Kirghiz, another Turkic people. As a result, the majority of tribal groups formerly under Uyghur control dispersed and moved out of Mongolia.

Uyghur kingdoms (9th–11th centuries)

According to the New Book of Tang, the Uyghurs who founded the Uyghur Khaganate dispersed after the fall of the Khaganate, to live among the Karluks and to places such as Gansu.[note 4] These Uyghurs soon founded two kingdoms and the easternmost state was the Ganzhou Kingdom (870–1036), with its capital near present-day Zhangye, Gansu, China. The modern Yugurs are believed to be descendants of these Uyghurs. Ganzhou was absorbed by the Western Xia in 1036.

The second Uyghur kingdom, the Kingdom of Qocho, also known as Uyghuristan in its later period, was founded in the Turpan area with its capital in Qocho (modern Gaochang) and Beshbalik. The Kingdom of Qocho lasted from the ninth to the fourteenth century and proved to be longer-lasting than any power in the region, before or since.[50] The Uyghurs were originally Manichaean, but converted to Buddhism during this period. Qocho accepted the Qara Khitai as its overlord in the 1130s, and in 1209 submitted voluntarily to the rising Mongol Empire. The Uyghurs of Kingdom of Qocho were allowed significant autonomy and played an important role as civil servants to the Mongol Empire, but was finally destroyed by the Chagatai Khanate by the end of the 14th century.[50][111]

Islamization

| Part of a series on Islam in China | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

|

History of Islam in China

|

||||||

|

Major figures

|

||||||

|

Culture

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

| ||||||

In the tenth century, the Karluks, Yagmas, Chigils and other Turkic tribes founded the Kara-Khanid Khanate in Semirechye, Western Tian Shan, and Kashgaria, and later conquered Transoxiana. The Karakhanid rulers were likely to be Yaghmas who were associated with the Toquz Oghuz, and some historians therefore see this as a link between the Karakhanid and the Uyghurs of the Uyghur Khaganate, although this connection is disputed by others.[112]

The Karakhanids converted to Islam in the tenth century beginning with Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan, the first Turkic dynasty to do so.[113] Modern Uyghurs see the Muslim Karakhanids as an important part of their history; however, Islamization of the people of the Tarim Basin was a gradual process. The Indo-Iranian Saka Buddhist Kingdom of Khotan was conquered by the Turkic Muslim Karakhanids from Kashgar in the early 11th century, but Uyghur Qocho remained mainly Buddhist until the 15th century, and the conversion of the Uyghur people to Islam was not completed until the 17th century.

.png)

The 12th and 13th century saw the domination by non-Muslim powers: first the Kara-Khitans in the 12th century, followed by the Mongols in the 13th century. After the death of Genghis Khan in 1227, Transoxiana and Kashgar became the domain of his second son, Chagatai Khan. The Chagatai Khanate split into two in the 1340s, and the area of the Chagatai Khanate where the modern Uyghurs live became part of Moghulistan, which meant "land of the Mongols". In the 14th century, a Chagatayid khan Tughluq Temür converted to Islam, Genghisid Mongol nobilities also followed him to convert to Islam.[114] His son Khizr Khoja conquered Qocho and Turfan (the core of Uyghuristan) in the 1390s, and the Uyghurs there became largely Muslim by the beginning of the 16th century.[115] After being converted to Islam, the descendants of the previously Buddhist Uyghurs in Turfan failed to retain memory of their ancestral legacy and falsely believed that the "infidel Kalmuks" (Dzungars) were the ones who built Buddhist structures in their area.[116]

From the late 14th through 17th centuries the Xinjiang region became further subdivided into Moghulistan in the north, Altishahr (Kashgar and the Tarim Basin), and the Turfan area, each often ruled separately by competing Chagatayid descendants, the Dughlats, and later the Khojas.[112]

Islam was also spread by the Sufis, and branches of its Naqshbandi order were the Khojas who seized control of political and military affairs in the Tarim Basin and Turfan in the 17th century. The Khojas however split into two rival factions, the Aqtaghlik Khojas (also called the Afaqiyya) and the Qarataghlik Khojas (the Ishaqiyya). The legacy of the Khojas lasted until the 19th century. The Qarataghlik Khojas seized power in Yarkand where the Chagatai Khans ruled in the Yarkent Khanate, forcing the Aqtaghlik Afaqi Khoja into exile.

Qing rule

In the 17th century, the Buddhist Dzungar Khanate grew in power in Dzungaria. The Dzungar conquest of Altishahr ended the last independent Chagatai Khanate, the Yarkent Khanate, after the Aqtaghlik Afaq Khoja attempt to gain aid from the 5th Dalai Lama and his Dzungar Buddhist followers to help him in his struggle against the Qarataghlik Khojas. The Aqtaghlik Khojas in the Tarim Basin then became vassals to the Dzungars.

The expansion of the Dzungars into Khalkha Mongol territory in Mongolia brought them into direct conflict with Qing China in the late 17th century, and in the process also brought Chinese presence back into the region a thousand years after Tang China lost control of the Western Regions.[117]

The Dzungar–Qing War lasted a decade. During the Dzungar conflict, two Aqtaghlik brothers, the so-called "Younger Khoja" (Chinese: 霍集占), also known as Khwāja-i Jahān, and his sibling, the Elder Khoja (Chinese: 波羅尼都), also known as Burhān al-Dīn, after being appointed as vassals in the Tarim Basin by the Dzungars, first joined the Qing and rebelled against Dzungar rule until the final Qing victory over the Dzungars, then they rebelled against the Qing, an action which prompted the invasion and conquest of the Tarim Basin by the Qing in 1759. The Uyghurs of Turfan and Hami such as Emin Khoja were allies of the Qing in this conflict, and these Uyghurs also helped the Qing rule the Altishahr Uyghurs in the Tarim Basin.[118][119]

The final campaign against the Dzungars in the 1750s ended with the Dzungar genocide. The Qing "final solution" of genocide to solve the problem of the Dzungar Mongols created a land devoid of Dzungars, which was followed by the Qing sponsored settlement of millions of other people in Dzungaria.[120][121] In northern Xinjiang, the Qing brought in Han, Hui, Uyghur, Xibe, Daurs, Solons, Turkic Muslim Taranchis and Kazakh colonists, with one third of Xinjiang's total population consisting of Hui and Han in the northern area, while around two thirds were Uyghurs in southern Xinjiang's Tarim Basin.[122] In Dzungaria, the Qing established new cities like Ürümqi and Yining.[123] The Dzungarian basin itself is now inhabited by many Kazakhs.[124] The Qing therefore unified Xinjiang and changed its demographic composition as well.[125]:71 The crushing of the Buddhist Dzungars by the Qing led to the empowerment of the Muslim Begs in southern Xinjiang, migration of Muslim Taranchis to northern Xinjiang, and increasing Turkic Muslim power, with Turkic Muslim culture and identity was tolerated or even promoted by the Qing.[125]:76 It was therefore argued by Henry Schwarz that "the Qing victory was, in a certain sense, a victory for Islam".[125]:72

In Beijing, a community of Uyghurs was clustered around the mosque near the Forbidden City, having moved to Beijing in the 18th century.[126]

The Ush rebellion in 1765 by Uyghurs against the Manchus occurred after several incidences of misrule and abuse that had caused considerable anger and resentment.[127][128][129] The Manchu Emperor ordered that the Uyghur rebel town be massacred, and the men were executed and the women and children enslaved.[130]

During the Dungan Revolt (1862–77), Andijani Uzbeks from the Khanate of Kokand under Buzurg Khan and Yaqub Beg expelled Qing officials from parts of southern Xinjiang and founded an independent Kashgarian kingdom called Yettishar "Country of Seven Cities". Under the leadership of Yaqub Beg, it included Kashgar, Yarkand, Khotan, Aksu, Kucha, Korla, and Turpan.

Large Qing dynasty forces under Chinese General Zuo Zongtang attacked Yettishar in 1876. After this invasion, the two regions of Dzungaria, which had been known as the Dzungar region or the Northern marches of the Tian Shan,[131][132] and the Tarim Basin, which had been known as "Muslim land" or southern marches of the Tian Shan,[133] were reorganized into a province named Xinjiang meaning "New Territory".[134][135]

Modern era

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1990 | 7,214,431 | — |

| 2000 | 8,405,416 | +1.54% |

| 2010 | 10,069,346 | +1.82% |

| Figures from Chinese Census | ||

In 1912, the Qing Dynasty was replaced by the Republic of China. By 1920, Pan-Turkic Jadidists had become a challenge to Chinese warlord Yang Zengxin who controlled Xinjiang. Uyghurs staged several uprisings against Chinese rule. Twice, in 1933 and 1944, the Uyghurs successfully gained their independence (backed by the Soviet Communist leader Joseph Stalin): the First East Turkestan Republic was a short-lived attempt at independence around Kashghar, and it was destroyed during the Kumul Rebellion by Chinese Muslim army under General Ma Zhancang and Ma Fuyuan at the Battle of Kashgar (1934). The Second East Turkestan Republic was a Soviet puppet Communist state that existed from 1944 to 1949 in the three districts of what is now Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture during the Ili Rebellion while the majority of Xinjiang was under the control of the Republic of China. Religious Uyghur separatists from the First East Turkestan Republic like Isa Yusuf Alptekin and Muhammad Amin Bughra opposed the Soviet Communist backed Uyghur separatists of the Second East Turkestan Republic under Ehmetjan Qasim and they supported the Republic of China during the Ili Rebellion.

Mao declared the founding of the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949. He turned the Second East Turkistan Republic into the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, and appointed Saifuddin Azizi as the region's first Communist Party governor. Many Republican loyalists fled into exile in Turkey and Western countries. The name Xinjiang was changed to Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, where Uyghurs are the largest ethnicity, mostly concentrated in the south-western Xinjiang.[136] The Xinjiang conflict is an ongoing separatist conflict in China's far-west province of Xinjiang, whose northern region is known as Dzungaria and whose southern region (the Tarim Basin) is known as East Turkestan. Uyghur separatists and independence movements claim that the region is not a part of China, but that the Second East Turkestan Republic was illegally incorporated by the PRC in 1949 and has since been under Chinese occupation. Uyghur identity remains fragmented, as some support a Pan-Islamic vision, exemplified by the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, while others support a Pan-Turkic vision, such as the East Turkestan Liberation Organization. A third group would like a "Uyghurstan" state, such as the East Turkestan independence movement. As a result, "[n]o Uyghur or East Turkestan group speaks for all Uyghurs, although it might claim to", and Uyghurs in each of these camps have committed violence against other Uyghurs who they think are too assimilated to Chinese or Russian society or are not religious enough.[137] Mindful not to take sides, Uyghur "leaders" such as Rebiya Kadeer mainly tried to garner international support for the "rights and interests of the Uyghurs", including the right to demonstrate, although the Chinese government has accused her of orchestrating the deadly July 2009 Ürümqi riots.[138]

Eric Enno Tamm's 2011 book states that, "Authorities have censored Uyghur writers and 'lavished funds' on official histories that depict Chinese territorial expansion into ethnic borderlands as 'unifications (tongyi), never as conquests (zhengfu) or annexations (tunbing)' "[139]

Persecution of Uyghurs in Xinjiang

Since 2014, Uyghurs in Xinjiang have been affected by extensive controls and restrictions upon their religious, cultural and social life.[140][141][142][143] In Xinjiang, the Chinese government has expanded police surveillance to watch for signs of "religious extremism" that include owning books about Uyghurs, growing a beard, having a prayer rug, or quitting smoking or drinking. The government had also installed cameras in the homes of private citizens.[144][145]

Further, at least 120,000 (and possibly over 1 million)[146] Uyghurs are detained in mass detention camps,[147] termed "re-education camps", aimed at changing the political thinking of detainees, their identities, and their religious beliefs.[148] Some of these facilities keep prisoners detained around the clock, while others release their inmates at night to return home. According to Chinese government operating procedures, the main feature of the camps is to ensure adherence to Chinese Communist Party ideology. Inmates are continuously held captive in the camps for a minimum of 12 months depending on their performance in Chinese ideology tests.[149] The New York Times has reported inmates are required to "sing hymns praising the Chinese Communist Party and write 'self-criticism' essays," and that prisoners are also subjected to physical and verbal abuse by prison guards.[144] Chinese officials are sometimes assigned to monitor the families of current inmates, and women have been detained due to actions by their sons or husbands.[144]

In 2017, Human Rights Watch released a report saying "The Chinese government agents should immediately free people held in unlawful 'political education' centers in Xinjiang, and shut them down."[150]

The government denied the existence of the camps initially, but have changed their stance since to claiming that the camps serve to combat terrorism and give vocational training to the Uyghur people.[151] Activists have called for the camps to be opened to visitors to prove their function. Media groups have reported that many in the camps were forcibly detained there in rough unhygienic conditions while undergoing political indoctrination.[152] The lengthy isolation periods between Uyghur men and women has been interpreted by some analysts as an attempt to inhibit Uyghur procreation in order to change the ethnic demographics of the country.[153]

An October 2018 exposé by the BBC News claimed, based on analysis of satellite imagery collected over time, that hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs must be interned in rapidly expanding camps.[154] It was also reported in 2019 that "hundreds" of writers, artists, and academics had been imprisoned, in what the magazine qualified as an attempt to "punish any form of religious or cultural expression" among Uyghurs.[155]

Parallel to the forceful detainment of millions of adults, in 2017 alone at least half a million children were also forcefully separated from their families, and placed in pre-school camps with prison-style surveillance systems and 10,000 volt electric fences.[156]

In 2019, a New York Times article reported that human rights groups and Uyghur activists said that the Chinese government was using technology from US companies and researchers to collect DNA from Uyghurs. They said China was building a comprehensive DNA database to be able to track down Uyghurs who were resisting the re-education campaign.[157]

Despite the ongoing repression of the Uyghurs as portrayed by Western media, there have been very few protests from Islamic countries against the internment and re-education of the ethnicity by the Chinese Communist Party. In December 2018, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) initially acknowledged the disturbing reports from the region but the statement was later retracted and replaced by the comment that the OIC "commends the efforts of the People's Republic of China in providing care to its Muslim citizens; and looks forward to further cooperation between the OIC and the People's Republic of China." Even Saudi Arabia, which host significant numbers of ethnic Uyghurs, have refrained from any official criticism of the Chinese government, possibly due to economic and political liaisons between China and many Islamic nations.[158][159] While the Turkish Foreign Ministry spokesperson denounced China for "violating the fundamental human rights of Uyghur Turks and other Muslim communities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region" in February 2019,[160][161] Turkish President Erdogan later said “It is a fact that the people of all ethnicities in Xinjiang are leading a happy life amid China's development and prosperity” while visiting China.[162] Erdogan also said that some people were seeking to "abuse" the Xinjiang crisis to jeopardize Turkey and China's economic relationship.[163][164][165]

The CPC is accused of cultural genocide for detaining 1 million Uyghurs in detention camps to change their political thinking, their identities, and their religious beliefs.[166] Satellite evidence suggests China destroyed more than two dozen Uyghur Muslim religious sites between 2016 and 2018.[167]

In July 2019, 22 countries, including Australia, United Kingdom, Canada, France, Germany and Japan, raised concerns about “large-scale places of detention, as well as widespread surveillance and restrictions, particularly targeting Uyghurs and other minorities in Xinjiang”.[168] The 22 ambassadors urged China to end arbitrary detention and allow “freedom of movement of Uyghurs and other Muslim and minority communities in Xinjiang”.[169] However, none of these countries were predominantly Islamic countries.[170]

On July 12, 2019, ambassadors from 37 countries issued a joint letter to the President of the UN Human Rights Council and the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights showing their support for China, despite condemnation by several states over the detention of as many as two million Uyghur Muslims. These countries included many African countries, Saudi Arabia, Russia, North Korea, Venezuela, Bolivia, Cuba, Belarus, Myanmar, the Philippines, Syria, Pakistan, Oman, Kuwait, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain.[171] On August 20, 2019, Qatar withdrew its signature from the letter, ending its support for China over its treatment of Muslims.[172]

In the late 2010s, the destruction of Uyghur cemeteries in Xinjiang raised concerns among activists.[173][174]

Uyghurs of Taoyuan, Hunan

Around 5,000 Uyghurs live around Taoyuan County and other parts of Changde in Hunan province.[175][176] They are descended from Hala Bashi, a Uyghur leader from Turpan (Kingdom of Qocho), and his Uyghur soldiers sent to Hunan by the Ming Emperor in the 14th century to crush the Miao rebels during the Miao Rebellions in the Ming Dynasty.[26][177] The 1982 census records 4,000 Uyghurs in Hunan.[178] They have genealogies which survive 600 years later to the present day. Genealogy keeping is a Han Chinese custom which the Hunan Uyghurs adopted. These Uyghurs were given the surname Jian by the Emperor.[179] There is some confusion as to whether they practice Islam or not. Some say that they have assimilated with the Han and do not practice Islam anymore and only their genealogies indicate their Uyghur ancestry.[180] Chinese news sources report that they are Muslim.[26]

The Uyghur troops led by Hala were ordered by the Ming Emperor to crush Miao rebellions and were given titles by him. Jian is the predominant surname among the Uyghur in Changde, Hunan. Another group of Uyghur have the surname Sai. Hui and Uyghur have intermarried in the Hunan area. The Hui are descendants of Arabs and Han Chinese who intermarried and they share the Islamic religion with the Uyghur in Hunan. It is reported that they now number around 10,000 people. The Uyghurs in Changde are not very religious and eat pork. Older Uyghurs disapprove of this, especially elders at the mosques in Changde and they seek to draw them back to Islamic customs.[181]

In addition to eating pork, the Uyghurs of Changde Hunan practice other Han Chinese customs, like ancestor worship at graves. Some Uyghurs from Xinjiang visit the Hunan Uyghurs out of curiosity or interest. Also, the Uyghurs of Hunan do not speak the Uyghur language, instead, they speak Chinese as their native language and Arabic for religious reasons at the mosque.[181]

Genetics

One study by Xu et al. (2008), using samples from Hetian (Hotan) only, found Uyghurs have about 60% European or South-West Asian ancestry and about 40% East Asian or Siberian ancestry.[182] Further study by the same team showed slightly greater European/West Asian component (52%) in the Uyghur population in southern Xinjiang, but only 47% in the northern Uyghur population.[183] A different study by Li et al. (2009) used a larger sample of individuals from a wider area, and found a higher East Asian component with about 70% with much more similarity to "Western East" Eurasians than East Asian populations, while European/West Asian component was about 30%.[184]

A study (2013) about the autosomal DNA shows that average Uyghurs are closest to other Turkic people in Central Asia and China. The analysis of the diversity of cytochrome B further suggests Uyghurs are closer to Chinese and Siberian populations than to various "Caucasoid" groups in West Asia or Europe.[185] A study on mitochondrial DNA (2013) (therefore the matrilineal genetic contribution) found the frequency of western Eurasian-specific haplogroup in Uyghurs to be 42.6%, and East Asian haplogroup to be 57.4%.[186]

A study on paternal DNA (2005) shows West Eurasian haplogroups in Uyghurs make up around 65% to 70%, and East Asian haplogroups around 30% to 35%.[187]

A 2017 genetic analysis of 951 samples of Uyghurs from 14 geographical subpopulations in Xinjiang observes a southwest and northeast differentiation in the population caused by the Tianshan Mountains that form a natural barrier, with gene flow from the east and west into these separated groups of people. The study identifies four major ancestral components that may have arisen from two earlier admixed groups: one from the West with European (25–37%) and South Asian ancestries (12–20%); another from the East with Siberian (15–17%) and East Asian ancestries (29–47%). It identifies an ancient wave of settlers that arrived around 3,750 years ago, dating that corresponds with the Tarim mummies of 4,000–2,000 years ago of a people with European features, and a more recent wave that occurred around 750 years ago. The analysis suggests the Uyghurs are most closely related to Central Asian populations such as the Hazaras of Afghanistan and the Uzbeks, followed by the East Asian and West Eurasian populations. While the Uyghur populations showed significant diversity, the differences between them are smaller than those between Uyghurs and non-Uyghurs.[188]

Culture

Religion

The ancient Uyghurs practiced Shamanism and Tengrism, then Manichaeism, Buddhism and Church of the East.[189][190] People in the Western Tarim Basin region began their conversion to Islam early in the Kara-Khanid Khanate period.[113] There had been Christian conversions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but were suppressed by the First East Turkestan Republic government agents.[191][192][193] Modern Uyghurs are primarily Muslim and they are the second-largest predominantly Muslim ethnicity in China after the Hui.[194]

The majority of modern Uyghurs are Sunnis, although additional conflicts exist between Sufi and non-Sufi religious orders.[194] While modern Uyghurs consider Islam to be part of their identity, religious observance varies between different regions. In general, Muslims in the southern region, Kashgar in particular, are more conservative. For example, women wearing the veil (brown cloth covering the head completely) are more common in Kashgar, but may not be found in some other cities.[195] There is also a general split between the Uyghurs and the Hui Muslims in Xinjiang and they normally worship in different mosques.[196] The Chinese government discourages religious worship among the Uyghurs and there is evidence of Uyghur mosques including historic ones being destroyed.[167]

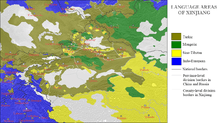

Language

The ancient people of the Tarim Basin originally spoke different languages such as Saka (Khotanese), Tocharian and Gandhari. The Turkic people who moved into region in the 9th century brought with them their languages which slowly supplanted the original tongues of the local inhabitants. By the 11th century, it was noted by Mahmud al-Kashgari that the Uyghurs (of Qocho) spoke a pure Turkic language, but they also still spoke another language among themselves and have two different scripts. He also noted that the people of Khotan did not know Turkic well and have their own language and script (Khotanese).[197] Writers of the Karakhanid period, al-Kashgari and Yusuf Balasagun, referred to their Turkic language as Khāqāniyya (meaning royal) or the "language of Kashgar" or simply Turkic.[198][199]

The modern Uyghur language is classified under the Karluk branch of the Turkic language family. It is closely related to Äynu, Lop, Ili Turki and Chagatay (the East Karluk languages) and slightly less closely to Uzbek (which is West Karluk). The Uyghur language is an agglutinative language and has a subject-object-verb word order. It has vowel harmony like other Turkic languages and has noun and verb cases, but lacks distinction of gender forms.[200]

Modern Uyghurs have adopted a number of scripts for their language. The Arabic script, known as the Chagatay alphabet, was adopted along with Islam. This alphabet is known as Kona Yëziq (old script). Political changes in the 20th century led to numerous reforms of the writing scripts, for example the Cyrillic-based Uyghur Cyrillic alphabet, a Latin Uyghur New Script and later a reformed Uyghur Arabic alphabet which represents all vowels unlike Kona Yëziq. A new Latin version, the Uyghur Latin alphabet, was also devised in the 21st century.

In the 1990s, many Uyghurs in parts of Xinjiang could not speak Mandarin Chinese.[201]

Literature

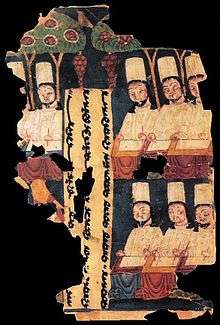

The literary works of the ancient Uyghurs were mostly translations of Buddhist and Manichaean religious texts,[202] but there were also narrative, poetic and epic works apparently original to the Uyghurs. However, it is the literature of Kara-Khanid period that is considered by modern Uyghurs to be the important part of their literary traditions. Amongst these are Islamic religious texts and histories of Turkic peoples and important works surviving from that era are Kutadgu Bilig, "Wisdom of Royal Glory" by Yusuf Khass Hajib (1069–70), Mahmud al-Kashgari's Dīwānu l-Luġat al-Turk, "A Dictionary of Turkic Dialects" (1072) and Ehmed Yükneki's Etebetulheqayiq. Modern Uyghur religious literature includes the Taẕkirah, biographies of Islamic religious figures and saints.[203][204][205] The Turki language Tadhkirah i Khwajagan was written by M. Sadiq Kashghari.[206] Between the 1600s and 1900s many Turki language tazkirah manuscripts devoted to stories of local sultans, martyrs and saints were written.[207] Perhaps the most famous and best-loved pieces of modern Uyghur literature are Abdurehim Ötkür's Iz, Oyghanghan Zimin, Zordun Sabir's Anayurt and Ziya Samedi's novels Mayimkhan and Mystery of the years.

Music

Muqam is the classical musical style. The 12 Muqams are the national oral epic of the Uyghurs. The muqam system was developed among the Uyghur in North-West China and Central Asia over approximately the last 1500 years from the Arabic maqamat modal system that has led to many musical genres among peoples of Eurasia and North Africa. Uyghurs have local muqam systems named after the oasis towns of Xinjiang, such as Dolan, Ili, Kumul and Turpan. The most fully developed at this point is the Western Tarim region's 12 muqams, which are now a large canon of music and songs recorded by the traditional performers Turdi Akhun and Omar Akhun among others in the 1950s and edited into a more systematic system. Although the folk performers probably improvised their songs as in Turkish taksim performances, the present institutional canon is performed as fixed compositions by ensembles.

The Uyghur Muqam of Xinjiang has been designated by U.N.E.S.C.O. as part of the Intangible Heritage of Humanity.[208]

Amannisa Khan, sometimes called Amanni Shahan (1526–1560), is credited with collecting and thereby preserving the Twelve Muqam.[209] Russian scholar Pantusov writes that the Uyghurs manufactured their own musical instruments; they had 62 different kinds of musical instruments and in every Uyghur home there used to be an instrument called a "duttar".

Dance

Sanam is a popular folk dance among the Uyghur people.[210] It is commonly danced by people at weddings, festive occasions, and parties.[211] The dance may be performed with singing and musical accompaniment. Sama is a form of group dance for Newruz (New Year) and other festivals.[211] Other dances include the Dolan dances, Shadiyane, and Nazirkom.[212] Some dances may alternate between singing and dancing, and Uyghur hand-drums called dap are commonly used as accompaniment for Uyghur dances.

Art

During the late-19th and early-20th centuries, scientific and archaeological expeditions to the region of Xinjiang's Silk Road discovered numerous cave temples, monastery ruins, and wall paintings, as well as miniatures, books, and documents. There are 77 rock-cut caves at the site. Most have rectangular spaces with rounded arch ceilings often divided into four sections, each with a mural of Buddha. The effect is of an entire ceiling covered with hundreds of Buddha murals. Some ceilings are painted with a large Buddha surrounded by other figures, including Indians, Persians and Europeans. The quality of the murals vary with some being artistically naïve while others are masterpieces of religious art.[213]

Education

Historically, the education level of Old Uyghur people was higher than the other ethnicities around them. The Buddhist Uyghurs of Qocho became the civil servants of Mongol Empire and Old Uyghur Buddhists enjoyed a high status in the Mongol empire. In the Islamic era, education may be provided by the mosques and madrassas. During the Qing era, Chinese Confucian schools were also set up in Xinjiang[214] and in the late 19th century Christian missionary schools.[215]

In the late nineteenth and early 20th century, school were often located in mosques and madrassah. Mosques ran informal schools, known as mektep or maktab, attached to the mosques,[216] The maktab provided most of the education and its curriculum was primarily religious and oral.[217] Boys and girls may be taught in separate schools, some of which may also offer modern secular subjects in the early 20th century.[214][215][218] In Madrasas, poetry, logic, Arabic grammar and Islamic law were taught.[219] In the early 20th century, the Jadidists Turkic Muslims from Russia spread new ideas on education[220][221][222][223][224] and popularized the identity of "Turkestani".[225]

In more recent times, religious education is highly restricted in Xinjiang and the Chinese authority had sought to eradicate any religious school they considered illegal.[226][227] Although Islamic private schools (Sino-Arabic schools (中阿學校)) have been supported and permitted by the Chinese government among Hui Muslim areas since the 1980s, this policy does not extend to schools in Xinjiang due to fear of separatism.[228][229][230]

Beginning in the early 20th century, secular education became more widespread. Early in the PRC era, Uyghurs had a choice of two separate secular school systems, one conducted in their own language and one offering instructions only in Chinese.[231] Many Uyghurs linked the preservation of their cultural and religious identity with the language of instruction in schools and therefore preferred the Uyghur language school.[215][232] However, from the mid-1980s onward, the Chinese government began to reduce teaching in Uyghur and starting mid-1990s also began to merge some schools from the two systems. By 2002, Xinjiang University, originally a bilingual institution, had ceased offering courses in the Uyghur language. From 2004 onward, the government policy is that classes should be conducted in Chinese as much as possible and in some selected regions, instruction in Chinese began in the first grade.[233] The level of education attainment among Uyghurs is generally lower than that of the Han Chinese; this may be due to the cost of education, the lack of proficiency in the Chinese language (now the main medium of instruction) among many Uyghurs and a poorer employment prospect for Uyghur graduates.[234] Uyghurs in China, unlike the Hui and Salar who are also mostly Muslim, generally do not oppose coeducation.[235] Girls however may be withdrawn from school earlier than boys.[215]

Traditional medicine

Uyghur traditional medicine is Unani (طب یونانی) medicine as used in the Mughal Empire.[236] Sir Percy Sykes described the medicine as "based on the ancient Greek theory" and mentioned how ailments and sicknesses were treated in Through Deserts and Oases of Central Asia.[237] Today, traditional medicine can still be found at street stands. Similar to other traditional medicine, diagnosis is usually made through checking the pulse, symptoms and disease history and then the pharmacist pounds up different dried herbs, making personalized medicines according to the prescription. Modern Uyghur medical hospitals adopted modern medical science and medicine and applied evidence-based pharmaceutical technology to traditional medicines. Historically, Uyghur medical knowledge has contributed to Chinese medicine in terms of medical treatments, medicinal materials and ingredients and symptom detection.[238]

Cuisine

Uyghur food shows both Central Asian and Chinese elements. A typical Uyghur dish is polu (or pilaf), a dish found throughout Central Asia. In a common version of the Uyghur polu, carrots and mutton (or chicken) are first fried in oil with onions, then rice and water are added and the whole dish is steamed. Raisins and dried apricots may also be added. Kawaplar (Uyghur: Каваплар ) or chuanr (i.e., kebabs or grilled meat) are also found here. Another common Uyghur dish is leghmen (لەغمەن, ләғмән), a noodle dish with a stir-fried topping (säy, from Chinese cai, 菜) usually made from mutton and vegetables, such as tomatoes, onions, green bell peppers, chili peppers and cabbage. This dish is likely to have originated from the Chinese lamian, but its flavor and preparation method are distinctively Uyghur.[239]

Uyghur food (Uyghur Yemekliri, Уйғур Йәмәклири) is characterized by mutton, beef, camel (solely bactrian), chicken, goose, carrots, tomatoes, onions, peppers, eggplant, celery, various dairy foods and fruits.

A Uyghur-style breakfast consists of tea with home-baked bread, hardened yogurt, olives, honey, raisins and almonds. Uyghurs like to treat guests with tea, naan and fruit before the main dishes are ready.

Sangza (ساڭزا, Саңза) are crispy fried wheat flour dough twists, a holiday specialty. Samsa (سامسا, Самса) are lamb pies baked in a special brick oven. Youtazi is steamed multi-layer bread. Göshnan (گۆشنان, Гөшнан) are pan-grilled lamb pies. Pamirdin (Памирдин) are baked pies stuffed with lamb, carrots and onions. Shorpa is lamb soup (شۇرپا, Шорпа). Other dishes include Toghach (Тоғач) (a type of tandoor bread) and Tunurkawab (Тунуркаваб). Girde (Гирде) is also a very popular bagel-like bread with a hard and crispy crust that is soft inside.

A cake sold by Uyghurs is the traditional Uyghur nut cake.[240][241][242]

Clothing and accoutrements

Chapan, a coat and Doppa, a headgear for men, is commonly worn by Uyghurs. Another headwear, Salwa telpek (salwa tälpäk, салва тәлпәк) is also worn by Uyghurs.[243]

In the early 20th century, face covering veils with velvet caps trimmed with otter fur were worn in the streets by Turki women in public in Xinjiang as witnessed by the adventurer Ahmad Kamal in the 1930s.[244] Travelers of the period Sir Percy Sykes and Ella Sykes wrote that in Kashghar women went into the bazar "transacting business with their veils thrown back" but mullahs tried to enforce veil wearing and were "in the habit of beating those who show their face in the Great Bazar".[245] In that period, belonging to different social statuses meant a difference in how rigorously the veil was worn.[246]

Muslim Turkestani men traditionally cut all the hair off their head.[247] Sir Aurel Stein observed that the Turki Muhammadan, accustomed to shelter this shaven head under a substantial fur-cap when the temperature is so low as it was just then.[248] No hair cutting for men took place on the ajuz ayyam, days of the year that were considered inauspicious.[249]

Yengisar is famous for manufacturing Uyghur handcrafted knives.[250][251][252] The Uyghur word for knife is pichaq (پىچاق, пичақ) and the word for knives is pichaqchiliq (پىچاقچىلىقى, пичақчилиқ).[253] Uyghur artisan craftsmen in Yengisar are known for their knife manufacture. Uyghur men carry such knives as part of their culture to demonstrate the masculinity of the wearer,[254] but it has also led to ethnic tension.[255][256] Limitations were placed on knife vending due to concerns over terrorism and violent assaults.[257]

Livelihood

Most Uyghurs are agriculturists. Cultivating crops in an arid region has made the Uyghurs excel in irrigation techniques. This includes the construction and maintenance of underground channels called karez that brings water from the mountains to their fields. A few of the well-known agricultural goods include apples (especially from Ghulja), sweet melons (from Hami), and grapes from Turpan. However, many Uyghurs are also employed in the mining, manufacturing, cotton, and petrochemical industries. Local handicrafts like rug-weaving and jade-carving are also important to the cottage industry of the Uyghurs.[258]

Historically, Uyghurs have received jobs through Chinese government affirmative action programs. [259] Uyghurs may also have difficulty receiving non-interest loans (per Islamic beliefs). [260] The general lack of Uyghur proficiency in Mandarin Chinese also creates a barrier to access private and public sector jobs. [261]

Names

Since the arrival of Islam, most Uyghurs use "Arabic names", but traditional Uyghur names and names of other origin are still used by some.[262] After the establishment of the Soviet Union, many Uyghurs who studied in Soviet Central Asia added Russian suffixes to Russify their surnames and make them look Russian.[263] Names from Russia and Europe are used in Qaramay and Ürümqi by part of the population of city-dwelling Uyghurs. Others use names with hard to understand etymologies, with the majority dating from the Islamic era and being of Arabic or Persian derivation.[264] Some pre-Islamic Uyghur names are preserved in Turpan and Qumul.[262]

See also

- History of the Uyghur people

- Kushan

- List of Uyghurs

- Meshrep

- Tocharians

- Uyghur Act

- Uyghurs in Beijing

- Uyghur Khaganate

- Uyghur timeline

- Xinjiang conflict

- Eretnids

Notes

- Native, here, is not synonymous with the term indigenous, but rather means "member/s of a nation".

- The term Turk was a generic label used by members of many ethnicities in Soviet Central Asia. Often the deciding factor for classifying individuals belonging to Turkic nationalities in the Soviet censuses was less what the people called themselves by nationality than what language they claimed as their native tongue. Thus, people who called themselves "Turk" but spoke Uzbek were classified in Soviet censuses as Uzbek by nationality.[48]

- This contrasts to the Hui people, called Huihui or "Hui" (Muslim) by the Chinese, and the Salar people, called "Sala Hui" (Salar Muslims) by the Chinese. Use of the term "Chan Tou Hui" was considered a demeaning slur.[83]

- "Soon the great chief Julumohe and the Kirghiz gathered a hundred thousand riders to attack the Uyghur city; they killed the Kaghan, executed Jueluowu, and burnt the royal camp. All the tribes were scattered – its ministers Sazhi and Pang Tele with fifteen clans fled to the Karluks, the remaining multitude went to Tibet and Anxi." (Chinese: 俄而渠長句錄莫賀與黠戛斯合騎十萬攻回鶻城,殺可汗,誅掘羅勿,焚其牙,諸部潰其相馺職與厖特勒十五部奔葛邏祿,殘眾入吐蕃、安西。)[110]

References

Citations

- "Uyghur in China". joshuaproject.net.

- 3-7 各地、州、市、县(市)分民族人口数 (in Chinese). Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2017-09-03.

- "'The entire Uyghur population is seemingly being treated as suspect': China's persecution of its Muslim minority". lse.ac.uk. LSE. Archived from the original on 22 September 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- Uyghur (in Russian). Historyland. Archived from the original on 2019-02-12. Retrieved 2018-05-03.

- "Ethnic groups of Kazakhstan in 2009". www.almaty-kazakhstan.net. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2009.

- Агентство Республики Каписью на 26,1% и составила 10098,6 тыс. человек. Увеличилась численность узбеков на 23,3%, составив 457,2 тыс. человек, уйгур - на 6%, составив 223,1 тыс. человек. Снизилась численность русских на 15,3%, составив 3797,0 тыс. человек; немцев - на 49,6%, составив 178,2 тыс. человек; украинцев – на 39,1%, составив 333,2 тыс. человек; татар – на 18,4%, составив 203,3 тыс. человек; других этносов – на 5,8%, составив 714,2 тыс. человек.

- "Домен cjes.ru продается". library.cjes.ru. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2019-02-10.

- "Уйгуры Узбекистана — Письма о Ташкенте". mytashkent.uz. Archived from the original on 2019-02-12. Retrieved 2019-02-10.

- Национальный статистический комитет Кыргызской Республики : Перепись населения и жилищного фонда Кыргызской Республики 2009 года в цифрах и фактах - Архив Публикаций - КНИГА II (часть I в таблицах) : 3.1. Численность постоянного населения по национальностям Archived 2012-03-08 at the Wayback Machine

- "Nitaqat rules for Palestinians and Turkistanis eased". arabnews.com. Saudi Labor Ministry. 2013-03-06. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- "China has turned Xinjiang into a police state like no other". The Economist. 31 May 2018.

- "Uighur abuse: Australia urged to impose sanctions on China". www.sbs.com.au. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- Shohret Hoshur; Shemshidin, Zubeyra (2010-04-06), "Pakistan Uyghurs in Hiding: Brothers blame raids and arrests on pressure from China", Radio Free Asia, archived from the original on 2010-05-13, retrieved 2010-05-11

- "Перепись населения России 2010 года". Archived from the original on 2012-02-01. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics (2017-02-08). "Census Profile, 2016 Census - Canada [Country] and Canada [Country]". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 2018-04-28.

- "Is their crossroads cuisine 'the next big thing'? Uyghurs hope so". Washington Post. 3 March 2017. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Hoshur, Shohret; Vandenbrink, Rachel (24 March 2012). "Japan Backs Uyghur Rights". Radio Free Asia. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- State statistics committee of Ukraine - National composition of population, 2001 census Archived 2014-10-08 at the Wayback Machine (Ukrainian)

- "Uighur, n. and adj.", Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Hahn 2006, p. 4.

- Drompp 2005, p. 7.

- "Uighur | History, Language, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2018-12-17. Retrieved 2018-12-17.

- "The mystery of China's celtic mummies". The Independent. London. August 28, 2006. Archived from the original on April 3, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- "Full Text of White Paper on History and Development of Xinjiang". en.people.cn. Archived from the original on 2019-06-25. Retrieved 2019-06-15.

- Dillon 2004, p. 24.

- "Ethnic Uygurs in Hunan Live in Harmony with Han Chinese". People's Daily. 29 December 2000. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007.

- "Ethno-Diplomacy: The Uyghur Hitch in Sino-Turkish Relations" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- George Friedman (19 November 2019). "The Pressure on China". Geopolitical Futures. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

1 in every 10 Uighurs are being detained in "re-education" camps

- Lipes, Joshua (November 24, 2019). "Expert Says 1.8 Million Uyghurs, Muslim Minorities Held in Xinjiang's Internment Camps". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- "China Uighurs: One million held in political camps, UN told". www.bbc.com. 2018-08-10. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "U.N. says it has credible reports China holds million Uighurs in secret camps". www.reuters.com. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "Former inmates of China's Muslim 're-education' camps tell of brainwashing, torture". www.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "Islamic Leaders Have Nothing to Say About China's Internment Camps for Muslims". foreignpolicy.com. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- "Inside the re-education camps China is using to brainwash muslims". Business Insider. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- Ramzy, Austin; Buckley, Chris (2019-11-16). "'Absolutely No Mercy': Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-11-16.

- Mair, Victor (13 July 2009). "A Little Primer of Xinjiang Proper Nouns". Language Log. Archived from the original on 18 July 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- Fairbank 1968, p. 364.

- Özoğlu 2004, p. 16.

- The Terminology Normalization Committee for Ethnic Languages of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (11 October 2006). "Recommendation for English transcription of the word 'ئۇيغۇر'/《维吾尔》". Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- Russell-Smith 2005, p. 33.

- "TURK BITIG". Archived from the original on 2014-10-06.

- Mackerras 1968, p. 224.

- Güzel 2002.

- Golden 1992, p. 155.

- Hakan Özoğlu, p. 16.

- Russell-Smith 2005, p. 32.

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1987), The Languages of China, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 185–6.

- Silver, Brian D. (1986), "The Ethnic and Language Dimensions in Russian and Soviet Censuses", in Ralph S. Clem (ed.), Research Guide to the Russian and Soviet Censuses, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 70–97.

- Mair 2006, pp. 137–8.

- James A. Millward & Peter C. Perdue (2004). "Chapter 2: Political and Cultural History of the Xinjiang Region through the Late Nineteenth Century". In S. Frederick Starr (ed.). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. M. E. Sharpe. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-7656-1318-9. Archived from the original on 2016-01-01. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article/34/10/2572/3864506

- "Uyghurs are hybrids".

- "Genetic testing reveals awkward-truth about Xinjiang's famous mummies". Khaleejtimes.com. 2005-04-19. Archived from the original on 2011-12-03. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- Wong, Edward (2008-11-19). "The Dead Tell a Tale China Doesn't Care to Listen To". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2016-11-21.

- Lattimore (1973), p. 237.

- Edward Balfour (1885). The cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia: commercial, industrial and scientific, products of the mineral, vegetable, and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures (3 ed.). LONDON: B. Quaritch. p. 952. Archived from the original on 2016-03-26. Retrieved 2010-06-28.(Original from Harvard University)

- Linda Benson (1990). The Ili Rebellion: the Moslem challenge to Chinese authority in Xinjiang, 1944–1949. M.E. Sharpe. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-87332-509-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2008). Community matters in Xinjiang, 1880–1949: towards a historical anthropology of the Uyghur (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 50. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Ondřej Klimeš (8 January 2015). Struggle by the Pen: The Uyghur Discourse of Nation and National Interest, c.1900-1949. BRILL. pp. 93–. ISBN 978-90-04-28809-6. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- Brophy, David (2005). "Taranchis, Kashgaris, and the 'uyghur Question' in Soviet Central Asia". Inner Asia. BRILL. 7 (2): 170. doi:10.1163/146481705793646892. JSTOR 23615693.

- Ondřej Klimeš (8 January 2015). Struggle by the Pen: The Uyghur Discourse of Nation and National Interest, c.1900-1949. BRILL. pp. 83–. ISBN 978-90-04-28809-6. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- Ondřej Klimeš (8 January 2015). Struggle by the Pen: The Uyghur Discourse of Nation and National Interest, c.1900-1949. BRILL. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-90-04-28809-6. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- Andrew D. W. Forbes (9 October 1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. CUP Archive. pp. 307–. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- Justin Jon Rudelson (1997). Oasis identities: Uyghur nationalism along China's Silk Road (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10787-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Ho-dong Kim (2004). Holy war in China: the Muslim rebellion and state in Chinese Central Asia, 1864–1877 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-8047-4884-1. Archived from the original on 2013-06-15. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Brophy, David (2005). "Taranchis, Kashgaris, and the 'uyghur Question' in Soviet Central Asia". Inner Asia. BRILL. 7 (2): 166. doi:10.1163/146481705793646892. JSTOR 23615693.

- Mir, Shabbir (May 21, 2015). "Displaced dreams: Uighur families have no place to call home in G-B". The Express Tribune. GILGIT. Archived from the original on May 22, 2015.

- Ho-dong Kim (2004). war in China: the Muslim rebellion and state in Chinese Central Asia, 1864–1877 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8047-4884-1. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0231139243. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Thum, Rian (6 August 2012). "Modular History: Identity Maintenance before Uyghur Nationalism". The Journal of Asian Studies. The Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 2012. 71 (3): 627–653. doi:10.1017/S0021911812000629. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- Rian Thum (13 October 2014). The Sacred Routes of Uyghur History. Harvard University Press. pp. 149–. ISBN 978-0-674-96702-1. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- Newby, L. J. (2005). The Empire And the Khanate: A Political History of Qing Relations With Khoqand c.1760-1860. Brill's Inner Asian Library. 16 (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 2. ISBN 978-9004145504. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2007). Situating the Uyghurs between China and Central Asia. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7546-7041-4. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- BROPHY, DAVID (2005). "Taranchis, Kashgaris, and the 'uyghur Question' in Soviet Central Asia (Inner Asia 7 (2))". Inner Asia. BRILL: 163–84. 7 (2): 169–170. doi:10.1163/146481705793646892. JSTOR 23615693.

- James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian crossroads: a history of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Arienne M. Dwyer; East-West Center Washington (2005). The Xinjiang conflict: Uyghur identity, language policy, and political discourse (PDF) (illustrated ed.). East-West Center Washington. p. 75, note 26. ISBN 978-1-932728-28-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-05-24. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Edward Allworth (1990). The modern Uzbeks: from the fourteenth century to the present : a cultural history (illustrated ed.). Hoover Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-8179-8732-9. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Akiner (28 October 2013). Cultural Change & Continuity In. Routledge. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-1-136-15034-0. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- Linda Benson (1990). The Ili Rebellion: The Moslem Challenge to Chinese Authority in Xinjiang, 1944-1949. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-0-87332-509-7. Archived from the original on 2016-01-01. Retrieved 2015-11-13.

- Suisheng Zhao (2004). A nation-state by construction: dynamics of modern Chinese nationalism (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-8047-5001-1. Retrieved 2011-06-12.

- Murray A. Rubinstein (1994). The Other Taiwan: 1945 to the present. M.E. Sharpe. p. 416. ISBN 978-1-56324-193-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- American Asiatic Association (1940). Asia: journal of the American Asiatic Association, Volume 40. Asia Pub. Co. p. 660. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- Garnaut, Anthony (2008), "From Yunnan to Xinjiang:Governor Yang Zengxin and his Dungan Generals" (PDF), Pacific and Asian History, Australian National University, p. 95, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-09.

- Simon Shen (2007). China and antiterrorism. Nova Publishers. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-60021-344-1. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Ondřej Klimeš (8 January 2015). Struggle by the Pen: The Uyghur Discourse of Nation and National Interest, c.1900-1949. BRILL. pp. 154–. ISBN 978-90-04-28809-6. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- Wei, C. X. George; Liu, Xiaoyuan (June 29, 2002). Exploring Nationalisms of China: Themes and Conflicts. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313315121. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2015 – via Google Books.

- Millward, James A. (June 29, 2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231139243. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2015 – via Google Books.

- Linda Benson (1990). The Ili Rebellion: The Moslem Challenge to Chinese Authority in Xinjiang, 1944-1949. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-0-87332-509-7. Archived from the original on 2016-01-01. Retrieved 2015-11-13.

- Gladney, Dru (2004). Dislocating China: Reflections on Muslims, Minorities, and Other Subaltern Subjects. C. Hurst. p. 195.

- Harris, Rachel (2004). Singing the Village: Music, Memory, and Ritual Among the Sibe of Xinjiang. Oxford University Press. pp. 53, 216.

- J. Todd Reed; Diana Raschke (2010). The ETIM: China's Islamic Militants and the Global Terrorist Threat. ABC-CLIO. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-0-313-36540-9.

- Benjamin S. Levey (2006). Education in Xinjiang, 1884-1928. Indiana University. p. 12. Archived from the original on 2017-01-09. Retrieved 2015-09-22.

- Justin Ben-Adam Rudelson; Justin Jon Rudelson (1997). Oasis identities: Uyghur nationalism along China's Silk Road. Columbia University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-231-10786-0. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- Dru C. Gladney (2005). Pál Nyíri; Joana Breidenbach (eds.). China inside out: contemporary Chinese nationalism and transnationalism (illustrated ed.). Central European University Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-963-7326-14-1. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1987). The Languages of China. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 185–6.

- Joscelyn, Thomas (April 21, 2009). "The Uighurs, in their words". The Long War Journal. Archived from the original on October 22, 2015.

- Balci, Bayram (1 January 2007). "Central Asian refugees in Saudi Arabia: religious evolution and contributing to the reislamization of their motherland". Refugee Survey Quarterly. 26 (2): 12–21. doi:10.1093/rsq/hdi0223.

- Balci, Bayram (Winter 2004). "The Role of the Pilgrimage in Relations between Uzbekistan and the Uzbek Community of Saudi Arabia" (PDF). Central Eurasian Studies Review. 3 (1): 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- Gardner Bovingdon (2010). "Chapter 1 - Using the Past to Serve the Present". The Uyghurs - strangers in their own land. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14758-3.

- Nabijan Tursun. "The Formation of Modern Uyghur Historiography and Competing Perspectives toward Uyghur History". The China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly. 6 (3): 87–100. Archived from the original on 2013-05-24.

- "Brief History of East Turkestan". World Uyghur Congress. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016.

- Susan J. Henders (2006). Susan J. Henders (ed.). Democratization and Identity: Regimes and Ethnicity in East and Southeast Asia. Lexington Books. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-7391-0767-6. Retrieved 2011-09-09.

- Reed, J. Todd; Raschke, Diana (2010). The ETIM: China's Islamic Militants and the Global Terrorist Threat. ABC-CLIO. p. 7. ISBN 978-0313365409. Archived from the original on 2016-01-01. Retrieved 2015-09-22.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0231139243. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press, New York. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- A. K Narain (March 1990). "Chapter 6 - Indo-Europeans in Inner Asia". In Denis Sinor (ed.). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9.

- Gardner Bovingdon. "Chapter 14 - Contested histories". In S. Frederick Starr (ed.). Xinjiang, China's Muslim Borderland. pp. 357–358. ISBN 978-0-7656-1318-9.

- Wechsler, Howard J. (1979). "T'ai-tsung (reign 624–49) the consolidator". In Twitchett, Denis (ed.). Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part 1. The Cambridge History of China. 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Golden 1992, p. 157.

- 新唐書/卷217下 - 维基文库,自由的图书馆. zh.wikisource.org (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2013-05-12.

- Dust in the Wind: Retracing Dharma Master Xuanzang's Western Pilgrimage. Rhythms Monthly. 2006. p. 480. ISBN 9789868141988.

- Millward 2007, p. 69.

- Golden, Peter. B. (1990), "The Karakhanids and Early Islam", in Sinor, Denis (ed.), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 357, ISBN 0-521-2-4304-1

- "Uyghur-History-in-Britanica". www.scribd.com. Retrieved 20 February 2013.