Women in the Australian military

Women currently make up 17.9% of the ADF workforce.[1] Women have served in Australian armed forces since 1899.[2] Until World War II women were restricted to the Australian Army Nursing Service. This role expanded in 1941–42 when the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), Australian Army and Royal Australian Air Force established female branches in which women took on a range of support roles. While these organisations were disbanded at the end of the war, they were reestablished in 1950 as part of the military's permanent structure. Women were integrated into the services during the late 1970s and early 1980s, but were not allowed to apply for combat roles until 2013. Women can now serve in all positions in the Australian Defence Force (ADF), including the special forces.

Current female participation rates

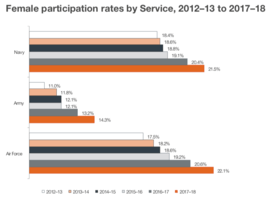

The ADF has an overall female participation rate of 17.9%. This has grown steadily since 2011, when Defence made increasing female participation a priority, with the intent of opening all previously gender restricted roles to women. Since 2012-13 defence has produced an annual ‘Women in the ADF’ report to assess their progress, as “increasing the participation of women in the ADF ensures that Defence secures the best possible talent available”.[3]

The percentage of women in each service as of the 2017-18 report is 21.5% in the Navy, 14.3% in the Army, and 22.1% in the Air Force.

History

Separate branches

Female service in the Australian military began in 1899 when the Australian Army Nursing Service was formed as part of the New South Wales colonial military forces. Army nurses formed part of the Australian contribution to the Boer War, and their success led to the formation of the Australian Army Nursing Reserve in 1902. The role of Australian women in World War I was focused mainly upon their involvement in the provision of nursing services. More than 2000 members of the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) served overseas during World War I as part of the Australian Imperial Force. At the end of the war the AANS returned to its pre-war reserve status.[4] In addition to the military nurses, a small group of civilian nurses dubbed the "Bluebirds" were recruited by the Australian Red Cross Society and served in French hospitals.[5]

Australian women during World War II

Australian women played a larger role in World War II. Many women wanted to play an active role, and hundreds of voluntary women's auxiliary and paramilitary organisations had been formed by 1940. These included the Women's Transport Corps, Women's Flying Club, Women's Emergency Signalling Corps and Women's Australian National Services.[6] In Brisbane alone there were six different organisations providing women with war-related training in July 1940, the largest of which was the Queensland-based Women's National Emergency Legion.[7] The Federal Government and military did not initially support women being trained to serve in the armed forces, however, and these organisations were not taken seriously by the general public.[6]

A shortage of male recruits forced the military to establish female branches in 1941 and 1942. The RAAF established the Women's Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF) in March 1941, the Army formed the Australian Women's Army Service (AWAS) in October 1941 and the Australian Army Medical Women's Service in December 1942 and the Women's Royal Australian Naval Service (WRANS) came into being in July 1942.[4] Dennis (2008)</ref> In 1944 almost 50,000 women were serving in the military and thousands more had joined the civilian Australian Women's Land Army (AWLA). Many of these women were trained to undertake skilled work in traditionally male occupations in order to free servicemen for operational service.[6] Women were also encouraged to work in industry and volunteer for air raid precautions duties or clubs for Australian and Allied servicemen.[8] The female branches of the military were disbanded after the war.[4]

Korean War

Manpower shortages during the Korean War led to the permanent establishment of female branches of the military. In 1951 the WRANS was reformed and the Army and Air Force established the Women's Australian Army Corps (WAAC) and Women's Royal Australian Air Force (WRAAF) respectively.[4] The proportion of women in the services was initially limited to four percent of their strength, though this was ignored by the RAAF.[9] The quota was lifted to 10 percent in the RAAF and RAN during the 1960s and 1970s while the Army recruited only on a replacement basis.[10]

Integration

The role of women in the Australian military began to change in the 1970s. In 1975, which was the International Year of Women, the service chiefs established a committee to explore opportunities for increased female participation in the military. This led to reforms which allowed women to deploy on active service in support roles, pregnancy no longer being grounds for automatic termination of employment and changes to leave provisions.[4][10] The WRAAF and WAAC were abolished in 1977 and 1979 respectively, with female soldiers being merged into the services. Equal pay was granted to servicewomen in 1979 and the WRANS was abolished in 1985.[4]

Despite being integrated into the military, there were still restrictions on female service. The ADF was granted an exemption from the Sexual Discrimination Act when it was introduced in 1984 so that it could maintain gender-based restrictions against women serving in combat or combat-related positions, which limited women to 40 percent of positions in the ADF.

Combat-related roles

As a result of personnel shortages in the late 1980s the restriction against women in combat-related positions was dropped in 1990, and women were for the first time allowed to serve in warships, RAAF combat squadrons and many positions in the Army. Women were banned from positions involving physical combat, however, and were unable to serve in infantry, armoured, artillery and engineering units in the Army and clearance diving and ground defence positions in the RAN and RAAF respectively.[10]

The ADF was not sufficiently prepared for integrating women into all units. Integration was hindered by entrenched discriminatory attitudes, sexual harassment and a perception that less demanding standards were applied to women.[4] This led to a number of scandals, including allegations of sexual harassment on board HMAS Swan, and the RAN's mishandling of these complaints.[10] These scandals did great harm to the ADF's reputation at the time when it most needed servicewomen.[4] The Defence Equality Organisation was established in 1997 in response to these problems, and it developed frameworks to facilitate the acceptance of women throughout the ADF.[11]

Deployments

Women have formed part of ADF deployments around the world since the early 1990s. Female sailors were sent into a combat zone for the first time on board HMAS Westralia in 1991, female medical personnel were deployed to Iraq, Western Sahara and Rwanda during the early 1990s and 440 of the 5,500 Australians deployed to East Timor in November 1999 were women.[12] Women also began to be promoted to command units in the late 1990s, and Air Commodore Julie Hammer became the first woman to reach one-star rank in 2000.[13]

In 2015, 335 women were participating in overseas operations in frontline support positions, including in Afghanistan.[14]

Women in Combat roles

On 27 September 2011, Defence Minister Stephen Smith announced that women will be allowed to serve in frontline combat roles by 2016.[15] Women became able to apply for all positions other than special forces roles in the Army on 1 January 2013; this remaining restriction removed in 2014 once the physical standards required for service in these units were determined. Women have been directly recruited into all frontline combat positions since late 2016.[16]

Women pilots and fighter pilots

Women have been eligible for flying roles in the RAAF since 1987, with the RAAF’s first women pilots awarded their ‘Wings’ in 1988. In 1995, the majority of restrictions were lifted allowing women to train as fast jet pilots. In 2016, 42 women in the RAAF had graduated the pilot's course and gained their "wings", flying planes such as C-17 Globemasters, C-130 Hercules and Wedgetail airborne early warning and control planes. Women have also qualified as fast jet aircrew, with the first F-111 navigators graduating in 2000. In December 2017, the first two female RAAF fighter pilots graduated, having completed 'High Sierra'- the three week intensive exercise that marks the culmination of 2OCU’s six-month long ‘opcon’ operational conversion course on the F/A-18 Hornet. [17] [18] [19]. A 2016 Australian Human Rights Commission report found that "the absence of female fast jet pilots is remarkable" given that the air forces of many comparable countries have had female fighter pilots since the 1990s. The report judged that there was no single factor responsible for this, rather, there are a series of structural and cultural factors that have prevented the progress of both female and male pilots in the Air Force.[20] The majority of the recommendations from this report were accepted and as of February 2019, women make up 38 of 752 pilots in the trained permanent Air Force (around 5.05%), and 126 of 498 Officer Aviation Cadets under training (25.3%).

Women in the Special forces

Women had been recorded as having passed the physical selection tests for the Army's elite Commando Regiment over 20 years before the announcement of allowing women in combat roles. These women were barred from joining due to their gender, including notable Lieutenant Colonel Fleur Froggatt. In January 2012, Senior Defence sources said that while several women had recently passed physical entry tests for special forces, they had prevented further advancement due to 'injury concerns'. In refusing to provide the numbers of women who had passed entry tests for the SAS or commandos, or when they passed, Defence cited security concerns.[21]

Growing numbers of Women in the ADF

Since the expansion in the number of positions available to women, there has been slow but steady growth in the percentage of female permanent defence personnel. In the 1989–1990 financial year women filled 11.4% of permanent ADF positions. In the 2005–2006 financial year women occupied 13.3% of permanent positions and 15.6% of reserve positions. During the same period the proportion of civilian positions filled by women in the Australian Defence Organisation increased from 30.8% to 40.3%.[22] The percentage of female members of the Australian labour force increased from approximately 41% to 45% between June 1989 and June 2006.[23]

In 2008 defence minister, Joel Fitzgibbon instructed the ADF to place a greater emphasis on recruiting women and addressing barriers to women being promoted to senior roles.[24][25]

In 2017-18, women made up 17.9% of The ADF workforce, and increase of 3.5 percentage points from 2013 (14.4%). There are still proportionally fewer women than men in senior leadership roles.[3]

Completion of Basic Training

A common misconception is that women are not as able to complete the physically and mentally demanding initial-entry training, and this may lead to their smaller overall employment rate. This is demonstrably incorrect. The 2016-17 Women in the ADF report states completion rates for women and men in initial training have been comparable since 2011.[26]

In fact, initial-entry training completion for females in 2017-18 were slightly higher than the males, with general entry (other ranks/ non-officer) 91.9 per cent for women; 90.2 per cent for men. Similarly, the 2017-18 officer trainee completion rate in the Navy and Airforce were at 87.8 per cent for women; 81.9 per cent for men, and the Army officer trainees at 66.7 per cent for women; 65.8 per cent for men.[3]

Recruitment goals and strategies

Each of the Services has set female participation targets to be achieved by 2023. These are 25 per cent for the Navy, 15 per cent for the Army and 25 per cent for the Air Force.

In August 2016 the Chief of Army Lieutenant General Angus Campbell AO, DSC, in an address to the Defence Force Recruiting Conference stated that his “number one priority.. with respect to recruitment is increasing our diversity; with a focus on women and Indigenous Australians”, and that “My aim is that women will make up 25% of the Army – based on analysis of best practice across like work environments globally (military and appropriately related industries). I want and need the Army to benefit from the full talent of the other half of our citizens.” [27] Since the Chief of Army has changed as of the 2nd of July 2018 to Lieutenant General Rick Burr AO, DSC, MVO, it is unknown whether he will strive to achieve the larger 25% target as his predecessor did.

Specialised media campaigns aimed at women and reduced initial minimum period of service (IMPS) contracts (eg. 2 years instead of 4 years for certain roles) has reportedly attracted more women in each branch.

The ‘Gap year’ program, aimed at younger women with only 1 year IMPS existing across each branch of ADF excels in female recruitment. Although small in number, 2018 recruitment rates of women were at 55% (Navy), 47% (Air force), and 34% (Army).[3]

See also

Notes

- Cabinet, Prime Minister and (2018-10-24). "Landmark moment for women in the ADF". www.pmc.gov.au. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- "A Short History of Australia's Servicewomen". Veterans SA. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2019). "Women in the ADF Report 2017-18: A Supplement To The Defence Annual Report 201718". Department of Defence. Retrieved 2019-05-17.

- Dennis et al. (2008), p. 605.

- Hetherington, Les (January 2009). "The Bluebirds in France". Wartime. 45: 58–60.

- Darian-Smith (1996), p. 62.

- "Women's War Effort". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 1 July 1940. p. 4. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- Darian-Smith (1996), pp. 62–63.

- Horner (2001), pp. 321–324.

- Horner (2001), p. 324.

- Horner (2001), p. 325.

- Horner (2001), p. 326.

- Horner (2001), pp. 325–326.

- "Path open for women to join special forces". SBS News. 25 February 2015.

- "Women cleared to serve in combat". ABC News. 27 September 2011.

- "Lifting of gender restrictions in the Australian Defence Force". Media release. Department of Defence. 1 February 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- "Australia's first female fighter pilots graduate". Australian Aviation. 17 December 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- Wroe, David (5 February 2016). "Women poised to start flying RAAF fighter jets". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "Breaking the fast jet ceiling". Australian Aviation. 8 March 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- Australian Human Rights Commission. "Improving Opportunities for Women to Become Fast Jet Pilots in Australia" (PDF). Freedom of information. Department of Defence. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- Dodd, Mark (24 January 2012). "SAS and commandos out of reach for elite women soldiers". The Australian.

- Khosa (2004). Page 52 and Australian Department of Defence (2006). 2005–06 Defence Annual Report. Page 281.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics Labour Force, Australia.

- Allard, Tom (2008-03-24). "Women, your armed forces need you". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- "Plan to put women in combat roles". News.com.au. 2008-03-02. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2018). "Women in the ADF Report 2016-17: A Supplement To The Defence Annual Report 2016-17" (PDF). Department of Defence. Retrieved 2019-05-17.

- Angus Campbell (4 August 2016). Chief of Army address to the Defence Force Recruiting conference (Speech). Retrieved 2019-05-20 – via www.army.gov.au.

References

- Adam-Smith, Patsy (1984). Australian Women at War. Melbourne: Thomas Nelson Australia. ISBN 0-17-006408-5.

- Darian-Smith, Kate (1996). "War and Australian Society". In Beaumont, Joan (ed.). Australia's War, 1939–1945. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-039-4.

- Dennis, Peter; et al. (2008). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (Second ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press Australia & New Zealand. ISBN 978-0-19-551784-2.

- Horner, David (2001). Making the Australian Defence Force. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554117-0.

- Khosa, Raspal (2004). Australian Defence Almanac 2004–05. Canberra: Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

- Parliamentary Library Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Group (2000). "Women in the armed forces: the role of women in the Australian Defence Force". Parliament of Australia Parliamentary Library. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2019). "Women in the ADF Report 2017-18: A Supplement To The Defence Annual Report 2017-18". Department of Defence. Retrieved 2019-05-17.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2018). "Women in the ADF Report 2016-17: A Supplement To The Defence Annual Report 2016-17" (PDF). Department of Defence. Retrieved 2019-05-17.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2019). "Department of Defence Annual Report 2017-18" (PDF). Department of Defence. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Women in the Australian military. |

- "Australian Women in War". National Foundation for Australian Women.