Mining in Australia

Mining in Australia has long been a significant primary industry and contributor to the Australian economy by providing export income, royalty payments and employment. Historically, mining booms have also encouraged population growth via immigration to Australia, particularly the gold rushes of the 1850s. Many different ores, gems and minerals have been mined in the past and a wide variety are still mined throughout the country.

History

Mining was an important early source of export income in Australian colonies and helped to pay for the imports needed for the growing colonial economies. Silver and later copper were discovered in South Australia in the 1840s, leading to the export of ore and the immigration of skilled miners and smelters. The first economic minerals in Australia were silver and lead in February 1841 at Glen Osmond, now a suburb of Adelaide in South Australia. Mines including Wheal Gawler and Wheal Watkins opened soon after.[1] The value of these mines was soon overshadowed by the discovery of copper at Kapunda (1842),[2] Burra (1845)[3] and in the Copper Triangle (Moonta, Kadina and Wallaroo) area at the top of Yorke Peninsula (1861).[4]

Gold rushes

In 1851, gold was found near Ophir, New South Wales. Weeks later, gold was found in the newly established colony of Victoria. Australian gold rushes, in particular the Victorian gold rush, had a major lasting impact on Victoria, and on Australia as a whole. The influx of wealth that gold brought soon made Victoria Australia's richest colony by far, and Melbourne the island's largest city. By the middle of the 1850s, 40% of the world's gold was produced in Australia.[5]

Australia's population changed dramatically as a result of the gold rushes: in 1851 the population was 437,655 and a decade later it was 1,151,957; the rapid growth was predominantly a result of the "new chums" (recent immigrants from the United Kingdom and other colonies of the Empire) who contributed the 'rush'.[6] Although most Victorian goldfields were exhausted by the end of the 19th century, and although much of the profit was sent back to the UK, sufficient wealth remained to fund substantial development of industry and infrastructure.

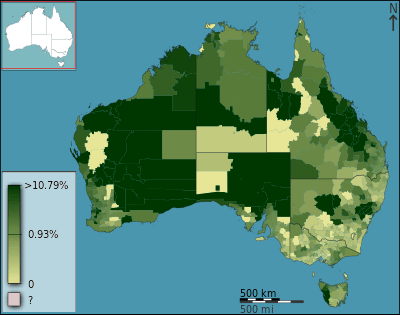

Location

Australia has mining activity in all of its states and territories. The Minerals Council of Australia estimates that 0.02% of Australia's land surface is directly impacted by mining.[7]

Particularly significant areas today include the Goldfields, Peel and Pilbara regions of Western Australia, the Hunter Region in New South Wales, the Bowen Basin in Queensland and Latrobe Valley in Victoria and various parts of the outback. Places such as Kalgoorlie, Mount Isa, Mount Morgan, Broken Hill and Coober Pedy are known as mining towns.

Major active mines in Australia include:

- Olympic Dam in South Australia, a copper, silver and uranium mine believed to have the world's largest uranium resource, and in 2018 producing 6% of world production

- Super Pit gold mine, which has replaced a number of underground mines at Boulder, Western Australia

- For a more comprehensive list of mines in Australia, see Mines in Australia

Minerals and resources

Large quantities of minerals and resources :

- Iron ore – Australia was the world's largest producer in 2019, supplying 580 million tonnes, 37% of the world's output (39% of the world's contained metal production).[8]

- Nickel – Australia was the world's fifth largest producer in 2019, producing 6.7% of world output.[9]

- Aluminium – Australia was the world's largest producer of bauxite in 2019 (27% of world production), and the second largest producer of alumina (15%), after China.[10]

- Copper – Australia was the world's 6th largest producer in 2019 (5% of world's production).[11]

- Gold – Australia was the second largest producer after China in 2019, producing 330 tonnes (11,000,000 ozt), 10% of the world's output.[12]

- Silver – In 2019 Australia was the sixth largest producer, producing 1,400 tonnes (45,000,000 ozt), 5% of the world's output.[13]

- Uranium – Australia is responsible for 12% of the world's production and was the world's third largest producer in 2018, after Kazakhstan and Canada.[14]

- Diamond – Australia has the third largest commercially viable deposits after Russia and Botswana. Australia also boasts the richest diamantiferous pipe with production reaching peak levels of 42 metric tons (41 LT/46 ST) per year in the 1990s.

- Opal – Australia is the world's largest producer of opal, being responsible for 95% of production.[15]

- Zinc – Australia was third to China and Peru in zinc production in 2019, producing 1.3 million tonnes, 10% of world production.[16]

- Coal – Australia is the world's largest exporter of coal and fourth largest producer of coal behind China, USA and India.[17]

- Oil shale – Australia has the sixth largest defined oil shale resources.[18]

- Petroleum – In 2019 Australia was the thirty-third largest producer of petroleum.

- Natural gas – Australia is world's largest exporter of LNG with 77.5 million tonnes in 2019.[19]

- Rare earth elements – In 2019 Australia was the third largest producer after China and USA, with 10% of the world's output.[20]

Much of the raw material mined in Australia is exported overseas to countries such as China for processing into refined product. Energy and minerals constitute two-thirds of Australia's total exports to China, and more than half of Australia's iron ore exports are to China.[21]

Statistical chart of Australia's major mineral resources

Australia ranks among the top 4 in economic resources for 21 primary industrial minerals, more than any other nation. Statistics are for December 2016.[22]

Units of measurement: t = tonne; kt = kilotonne (1,000 t); Mt = million tonne (1,000,000 t); Mc = million carat (1,000,000 c)

| Mineral | Unit of Measurement | Demonstrated Economic Resources |

World Ranking of Resources |

% of World Resources |

Production (2016) | World Ranking of Production |

% of World Production |

Years of Resources at Current Production Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimony | kt content | 139 | 4 | 9 | 5.5 | 4 | 4 | 25 |

| Bauxite | Mt ore | 6,005 | 2 | 22 | 82.15 | 1 | 31 | 73 |

| Coal, Black | Mt | 64,045 | 4 | 10 | 566.3 | 4 | 7 | 113 |

| Coal, Brown (lignite) | Mt | 66,439 | 2 | 24 | 63.3 | 5 | 6 | 1,050 |

| Cobalt | kt content | 1164 | 2 | 14 | 5.47 | 5 | 4 | 213 |

| Copper | Mt content | 87.78 | 2 | 12 | .95 | 5 | 5 | 92 |

| Diamond (industrial) | Mc | 115.84 | 3 | 18 | 13.96 | 2 | 24 | 8 |

| Gold | t content | 9,800 | 1 | 17 | 288 | 2 | 9 | 34 |

| Iron ore | Mt ore | 49,588 | 1 | 29 | 858 | 1 | 38 | 58 |

| Lead | Mt content | 24.09 | 1 | 40 | .45 | 2 | 9 | 54 |

| Lithium | kt content | 2,730 | 3 | 18 | 14 | 1 | 41 | 195 |

| Manganese | Mt ore | 219 | 4 | 13 | 3.2 | 4 | 9 | 68 |

| Nickel | Mt content | 18.5 | 1 | 24 | .204 | 5 | 9 | 91 |

| Rare Earth Elements | Mt ore | 3.43 | 6 | 3 | .014 | 2 | 11 | 245 |

| Silver | kt content | 89.29 | 2 | 16 | 1.42 | 5 | 5 | 63 |

| Tin | kt content | 486 | 4 | 10 | 6.64 | 7 | 2 | 73 |

| Titanium | Mt ore | 276.1 | 2 | 17 | 1.7 | 2 | 10 | 162 |

| Tungsten | kt content | 391 | 2 | 12 | .11 | 12 | .40 | 1,151 |

| Uranium | kt content | 1,212 | 1 | 29 | 6.31 | 3 | 10 | 192 |

| Vanadium | kt content | 2,111 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Zinc | Mt content | 63.5 | 1 | 28 | .884 | 3 | 7 | 75 |

| Zircon | Mt ore | 72.1 | 1 | 67 | .60 | 1 | 31 | 120 |

Coal mining

Coal is mined in every state of Australia except South Australia. It is used to generate electricity and is exported. 54% of the coal mined in Australia is exported, mostly to eastern Asia. In 2000/01, 258.5 million tonnes of coal was mined, and 193.6 million tonnes exported, rising to 261 million tonnes of exports in 2008–09.[17] Coal also provides about 85% of Australia's electricity production.[23] Australia is the world's leading coal exporter.[24]

Uranium mining

Uranium mining in Australia began in the early 20th century in South Australia. At 2016 Australia contained 29% of the world's defined uranium resources. The three largest uranium mines in the country are Olympic Dam, Ranger Uranium Mine and Beverley Uranium Mine. Future production is expected from Honeymoon Uranium Mine and the planned Four Mile Uranium Mine.

Entrepreneurs and magnates

At various stages in the history of the mining industry in Australia, individual mining managers, directors and investors have gained significant wealth and the subsequent publicity. In most cases the individuals are designated Mining Magnates or Australian mining entrepreneurs.

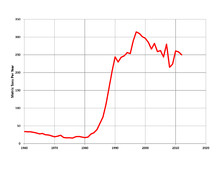

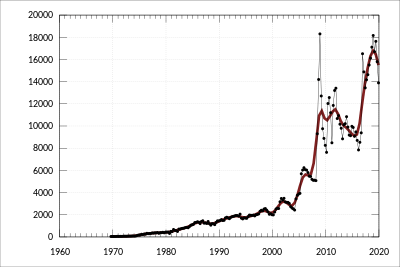

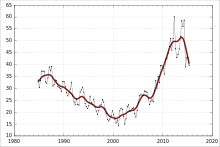

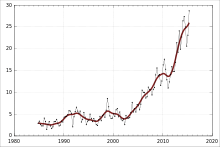

Economics

A number of large multinational mining companies including BHP Billiton, Newcrest, Rio Tinto, Alcoa, Chalco, Shenhua (a Chinese mining company), Alcan and Xstrata operate in Australia. There are also a lot of small mining and mineral exploration companies listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX). Overall, the resources sector represents almost 20% of the ASX market by capitalisation, and almost one third of the companies listed.[26]

Mining contributes about 5.6% of Australia's Gross Domestic Product. This is up from only 2.6% in 1950, but down from over 10% at the time of federation in 1901.[27] In contrast, mineral exports contribute around 35% of Australia's exports. Australia is the world's largest exporter of coal (35% of international trade), iron ore, lead, diamonds, rutile, zinc and zirconium, second largest of gold and uranium, and third largest of aluminium.[28] Japan was the major purchaser of Australian mineral exports in the mid-1990s.[5]

Of the developed countries, perhaps only Canada and Norway have mining as such a significant part of the economy; for comparison, in Canada mining represents about 3.6% of the Canadian economy and 32% of exports,[29] and in Norway mining, dominated by petroleum, represents about 19% of GDP and 46% of exports.[30] By comparison, in the United States mining represents only about 1.6% of GDP.[31]

The mining sector employs a relatively small number of people, about 2.0% of the total labour force.[32]

Technology and services

Australia's mining services, equipment, and technology exports are over $2 billion annually.[33]

Environment and politics

Australia is the world’s third largest exporter of fossil fuel carbon dioxide-emissions potential.[34] “Australia mines about 57 tonnes of CO2 potential per person each year, about 10 times the global average”.[34]

Mining has had a substantial environmental impact in some areas of Australia. Historically, the Victorian gold rush was the start of the economic growth of the country, leading to major increases in population. However, it also resulted in deforestation, consequent erosion, and pollution in the areas that were mined.[35] The effects on the landscape near Bendigo and Ballarat can still be seen today. Queenstown, Tasmania's mountains were also completely denuded through a combination of logging and pollution from a mine smelter, and remain bare today. It is estimated that 10 million hectares of land have been affected throughout the history of mining in Australia.[7] Because Australia's mines are distributed across varying climates the knowledge gained from one mine's restoration does not easily extrapolate to other sites.[7]

Uranium mining has been controversial, partly for its alleged environmental impact but more so because of its end uses in nuclear power and nuclear weapons. The Australian Labor Party, one of Australia's two major parties, maintains a policy of "no new uranium mines". As of 2006, the increased world demand for uranium has seen some pressure, both internally and externally on the ALP, for a policy change.[36] Australia is a participant in international anti-proliferation efforts designed to ensure that no exported uranium is used in nuclear weapons.[37]

Mining disasters

New Australian Gold Mine

Creswick in the Victorian goldfields was the site of The New Australasian No.2 Deep Lead Gold Mine. At 4:45 am, Tuesday 12 December 1882, 29 miners became trapped underground by flood waters that came from the flooded parallel-sunk No.1 mine shaft, only five men survived and made it to the surface. Despite two days of frantic pumping the waters filled the mine shaft. The trapped men scrawled last notes to their loved ones on billy cans before they drowned. Some of these have been kept and still bear the messages. The men that perished left 17 widows and 75 dependent children.[38]

Mount Kembla

In 1883 a coal mine was opened near Mount Kembla in the Illawarra District of New South Wales. In 1902 there was an explosion in the mine and 96 men and boys lost their lives, either while at work or in the course of trying to save the lives of others. Every family in the village lost a relative. A service of commemoration is held annually on 31 July at the Mount Kembla Soldiers' and Miners' Memorial Church. This is the worst mining disaster in Australia's history.[39]

Balmain Colliery

Balmain Colliery was located in Birchgrove, New South Wales and produced coal from 1897 until 1931 and natural gas until 1945. During this period, 10 miners lost their lives in three separate incidents:

1900 On 17 March 1900, six miners were being lowered down the Birthday shaft. At 1,424 feet the bucket they were travelling in caught on a projection, tipped over and five of the six men fell to their death in the shaft. As a result of this accident, the Mining Act was amended to provide guide rails in shafts to prevent bucket swinging or overturning.[40]

1932 In 1932, a year after the mine closed, a six-inch bore was sunk below the Birthday shaft to pipe Natural Gas to the surface. During the sinking of the bore, two men were killed when the gas ignited and exploded.[40]

1945 During the sealing of the Birthday shaft on 20 April 1945, a rudimentary test was being undertaken which ignited escaping gas and caused an explosion below the seal. The company manager and two men were killed in the accident and another two men injured.[40]

North Mount Lyell

On 12 October 1912, the North Mount Lyell Fire caused the death of 42 miners, and required breathing apparatus to be transported from Victorian mines at great speed, to rescue trapped miners. The subsequent royal commission was inconclusive as to the cause.

Mount Mulligan

The 1921 Mount Mulligan mine disaster occurred in Far North Queensland. The coal dust explosion killed seventy-five men.

Moura

Four serious accidents have occurred at mines in the Central Queensland town of Moura. The first accident took the lives of 13 men in September 1975. In July 1986 there was an explosion at Moura Number 4 Mine. 12 coal miners lost their lives in this disaster that sparked controversy after experts claimed the accident was avoidable. Another explosion killed two men in January 1994 and just eight months later another explosion deep underground took the lives of 11 men.[41]

Bronzewing

On 26 June 2000, at the Bronzewing Gold Mine in Western Australia (400 kilometres from Kalgoorlie), 18,000 cubic metres of sand-slurry, sludge, mud and rock broke through a storage wall. Two men (Timothy Lee Bell, 21, Shane Hamill, 45) were killed and eight escaped the 'accident'. It took over a month to retrieve the men from the site.

Bulli

1887 At 2.30 pm on 23 March 1887, an explosion at the mine in Bulli in New South Wales killed 81 people.[42] A special commission was set up to investigate the explosion and concluded:

..that the explosion was caused by marsh gas or carbonic hydrate that had accumulated at the face. That the immediate cause was probably the flame from an overcharged shot fired by a miner in the coal in No. 2 Heading.

This gas explosion propagated a coal dust explosion and travelled towards the fresh air at the surface. The commission was also of the opinion that the Deputy, Overman and to a lesser extent the Manager, were all guilty of contributing negligence.[43]

1965 On 9 November 1965, a pocket of gas ignited in a panel several hundred yards from the main shaft and killed four miners. Ten mining rescue teams and the Southern Mines Rescue Station worked all night to extinguish the fire.[44]

Box Flat Mine

At the Box Flat Mine in Swanbank, South East Queensland, 17 miners were lost after an underground gas explosion occurred on 31 July 1972.[45] Another man died later from injuries sustained in the explosion. The mine tunnel mouths were sealed and the mine closed shortly after.[45]

Australian mining in literature, art and film

- Henry Lawson, His Father's Mate from While The Billy Boils, 1896 (short story)

- Nickel Queen, based on the Western Australian nickel boom of the late 1960s

- Colin Thiele, The Fire in the Stone (book which became a film)

- Wendy Richardson, Windy Gully 1989 Currency Press (play)

- Conal Fitzpatrick, Kembla- The Book of Voices 2002 Kemblawarra Press (poetry) ISBN 0-9581287-0-7

- Henry Handel Richardson, The Fortunes of Richard Mahony: Australia Felix Takes place in the chaos of the early Ballarat goldrush.

- Richard Lowenstein, Strikebound (1984 film).

- Tim Burstall, The Last of the Knucklemen (1979 film, based on the play by John Power, who also wrote a novelisation of the film).

- Kriv Stenders, Red Dog (2011 film, based on the true story)

See also

- Economy of Australia

- Mining in the Northern Territory

- Mining in Western Australia

- NSW Minerals Council

- Uranium mining controversy in Kakadu National Park

References

- "The Glen Osmond Mines". South Australian History. Flinders Ranges Research. Retrieved 5 June 2006.

- "Kapunda". South Australian History. Flinders Ranges Research. Retrieved 6 June 2006.

- "Burra". South Australian History. Flinders Ranges Research. Retrieved 6 June 2006.

- "The Moonta Mine". South Australian History. Flinders Ranges Research. Retrieved 6 June 2006.

- Sharieff, Afzal; Masood Ali Khan; A Balakishan (2007). Encyclopedia of World Geography: Volume 23, Australia and its Geography. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. pp. 13–14. ISBN 81-7625-773-7.

- Caldwell, J. C. (1987). "Chapter 2: Population". In Wray Vamplew (ed.). Australians: Historical Statistics. Broadway, New South Wales, Australia: Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates. pp. 23 and 26. ISBN 0-949288-29-2.

- Grant, Carl (2013). "State-and-Transition Models for Mining Restoration in Australia". In Suding, Katharine N.; Hobbs, Richard J. (eds.). New Models for Ecosystem Dynamics and Restoration. Peter Society for Ecological Restoration International. p. 280. ISBN 9781610911382. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- Tuck, Christopher A. (20 January 2020). "Iron ore". Mineral commodity summaries 2020 (PDF). Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-1-4113-4362-7. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- McRae, Michele E. (20 January 2020). "Nickel". Mineral commodity summaries 2020 (PDF). Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-1-4113-4362-7. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- Bray, E. Lee (20 January 2020). "Bauxite and alumina". Mineral commodity summaries 2020 (PDF). Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-1-4113-4362-7. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- Flanagan, Daniel M. (20 January 2020). "Copper". Mineral commodity summaries 2020 (PDF). Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-1-4113-4362-7. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- Sheaffer, Kristin N. (20 January 2020). "Gold". Mineral commodity summaries 2020 (PDF). Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-1-4113-4362-7. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- George, Micheal W. (20 January 2020). "Silver". Mineral commodity summaries 2020 (PDF). Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-1-4113-4362-7. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- "World Uranium Mining". London: World Nuclear Association. August 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Minerals: Opal". Primary Industries and Resources South Australia. 20 August 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- Tolcin, Amy C. (20 January 2020). "Zinc". Mineral commodity summaries 2020 (PDF). Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 190–191. ISBN 978-1-4113-4362-7. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- "The Australian Coal Industry – Coal Exports". Australian Coal Association. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Oil shale in the world". Enefit. Amman, Jordan. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- "Australia becomes the largest liquefied natural gas exporter in the world". The Canberra Times. 7 January 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Gambogi, Joseph (20 January 2020). "Rare earths". Mineral commodity summaries 2020 (PDF). Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-4113-4362-7. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- The Hon De-Anne Kelly MP, Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Trade (3 May 2006). "Speech at the Australia China Business Council, Queensland Branch Business Dinner". Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- Britt, A., Summerfield, D., Senior, A., Kay, P., Huston, D., Hitchman, A., Hughes, A., Champion, D., Simpson, R., Sexton, M. and Schofield, A. (2017). "Australia's Identified Mineral Resources 2017" (pdf). Canberra: Geoscience Australia: 10. ISSN 1327-1466. Retrieved 19 March 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "The Importance of Coal in the Modern World – Australia". Gladstone Centre for Clean Coal. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- International Energy Agency. (31 August 2008) Coal Information 2008. Organization for Economic Cooperation & Development. ISBN 92-64-04241-5

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "ASX and Australian mining". Australian Stock Exchange. Archived from the original on 22 April 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- "1301.0 – Year Book Australia, 2005". 21 January 2005. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- The Hon Peter Costello, MP, Treasurer of Australia (5 June 2002). "Address to the Minerals Council of Australia, 2002 Minerals Industry Dinner". speech. Government of Australia. Archived from the original on 20 August 2006. Retrieved 18 June 2006.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Natural Resources Canada. "Canadian Minerals Yearbook, 2004". government of Canada. Archived from the original on 16 June 2006. Retrieved 19 June 2006.

- Statistics Norway. "Statistical Yearbook 2005". Government of Norway. Retrieved 19 June 2006..

- Bureau of Economic Analysis. "Gross-Domestic-Product-by-Industry Accounts". United States government. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2006.

- "Table 01:Employed people by industry—Feb 2018 and Feb 2019 (quarterly, trend), Original". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 10 April 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- "Mining Capability Overview". Austrade. Archived from the original on 14 February 2006. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- Kilvert, Nick (18 August 2019). "Australia is the world's third-largest exporter of CO2 in fossil fuels, report finds". ABC News. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- "Deforestation – Gold". Special Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 19 June 2006.

- Patrick Walters & Joseph Kerr (4 April 2006). "PM threatens ALP on China uranium deal". The Australian. Archived from the original on 28 July 2007. Retrieved 19 June 2006.

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (2005). "Weapons of Mass Destruction: Australia's Role in Fighting Proliferation". Government of Australia. Archived from the original on 26 May 2006. Retrieved 19 June 2006.

- Gold-Net Australia Online – May 1999

- Stuart Piggin and Henry Lee, The Mount Kembla Disaster, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1992

- Peter Reynolds, Balmain Places 2 – The Coal Mine Under The Harbour , Architectural History Research Unit, University of New South Wales, 1996, ISBN 0-908502-54-0

- Barwick, John (1999). Australia's worst disasters: mining disasters. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Heinemann Library. pp. 24–25. ISBN 1-86391-886-8.

- Wollongong City Library, Bulli – History Archived 19 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2/11/06.

- Illawarra Coal, Bulli Colliery Gas Explosion- 1887. Retrieved 2/11/06.

- Illawarra Coal, Bulli Colliery Underground Fire – 1965. Retrieved 2/11/06.

- Craig Wallace (4 June 2009). "Q150 bridge naming kicks off with Box Flat Bridge". Ministerial Media Statement. Department of the Premier and Cabinet. Retrieved 25 October 2010.