White Colombians

White Colombians are the Colombian descendants of European and Middle Eastern people. According to the 2005 Census 85% of Colombians do not identify with any ethnic group, thus being either White or Mestizo, which are not categorized separately. It is nevertheless estimated that 37% of the Colombian population can be categorized as white, forming the second largest racial group after Mestizo Colombians (49%).[2][3][4]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| approx. 9,470,000 to 17,519,500 (37% of the population[1]) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Throughout the nation, especially in the Andean Region, Caribbean Region and the major cities. | |

| Languages | |

| Predominantly Colombian Spanish (German · English · French · Italian and some other languages are spoken by minorities) | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity (Roman Catholic, Protestant, other Christians), Irreligion, Islam, and Judaism |

Numbers and distribution

The various racial groups exist in differing concentrations throughout the nation, in a pattern that to some extent goes back to colonial origins. Whites tend to live all throughout the country, mainly in the urban centers and the burgeoning highland and coastal cities.[5] The Paisa Region and Bogotá, the country's capital and largest city metropolitan region, have a large percentage of White Colombians.

History

Colonial period

The presence of Whites in Colombia began in 1510 with the colonization of San Sebastián de Urabá. In 1525, settlers founded Santa Marta, the oldest Spanish city still in existence in Colombia. Many Spaniards came searching for gold, while others established themselves as leaders of the social organizations teaching the Christian faith and the ways of their civilization. Christian priests would provide education to American Indians. Within 100 years after the first Spanish settlement, nearly 95 percent of all Native Americans in Colombia had died. The majority of the deaths were due to diseases from Europe, such as measles and smallpox. Some Amerindians were also killed in armed conflicts with their new neighbours.

Immigration from Europe

Basque priests introduced handball into Colombia.[6] Besides business, Basque immigrants in Colombia were devoted to teaching and public administration.[6] In the first years of the Andean multinational company, Basque sailors navigated as captains and pilots on the majority of the ships until the country was able to train its own crews.[6]. In Bogota, there is a small colony of thirty to forty families who emigrated as a consequence of the Spanish Civil War.[7][7]

The first German immigrants arrived in the 16th century contracted by the Spanish Crown, and included explorers such as Ambrosio Alfinger. There was another small wave of German immigrants at the end of the 19th and beginning of 20th century including Leo Siegfried Kopp, the founder of the famous Bavaria Brewery. SCADTA, a Colombian-German air transport corporation which was established by German expatriates in 1919, was the first commercial airline in the western hemisphere.[8]

In December 1941 the United States government estimated that there were at least 4,000 Germans living in Colombia.[9] There were some Nazi agitators in Colombia, such as Barranquilla businessman Emil Prufurt,[9] but the majority was apolitical. Colombia asked Germans who were on the U.S. blacklist to leave and allowed Jewish and German refugees in the country illegally to stay.[9]

Immigration from the Middle East

Colombia was one of early focus of Sephardi immigration.[10] Jewish converts to Christianity and some crypto-Jews also sailed with the early explorers. It has been suggested that the present day culture of business entrepreneurship in the region of Antioquia and Valle del Cauca is attributable to Sephardi immigration.[11]

The largest wave of Middle Eastern immigration began around 1880, and remained during the first two decades of the 20th century. They were mainly Maronite Christians from Lebanon, Syria and Ottoman Palestine, fleeing financial hardships and the repression of the Turkish Ottoman Empire. When they were first processed in the ports of Colombia, they were classified as Turks.

During the early part of the 20th century, numerous Jewish immigrants came from Greece, Turkey, North Africa and Syria. Shortly after, Jewish immigrants began to arrive from Germany and Eastern Europe.[9] Armenians, Lebanese, Syrians,[12] Palestinians and some Israelis[13] continue since then to settle in Colombia.[12]

More than 700,000 Colombians have partial Middle Eastern descent.[14] Due to poor existing information it's impossible to know the exact number of people that immigrated to Colombia. A figure of 50,000-100,000 from 1880 to 1930 may be reliable.[12] Whatever the figure, Lebanese are perhaps the biggest immigrant group next to the Spanish since independence.[12] Cartagena, Cali, and Bogota were among the cities with the largest number of Arabic-speaking representatives in Colombia in 1945.[12]

Ethnic breakdown

White Colombians are mainly of Spanish descent, who arrived in the beginning of the 16th century when Colombia was part of the Spanish Empire. During the 19th and 20th centuries, other European and Middle Eastern peoples migrated to Colombia, notably Lebanese as well as Germans, Italians, Lithuanians, French, and British among others.

Religion

The most predominant religion is Christianity, particularly Roman Catholicism. Under 1% practice Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism. Despite strong numbers of Christian adherents, 35.9% of Colombians reported that they did not practice their faith actively.[15]

Notable Colombians

Politics

- Francisco de Paula Santander - first President of Colombia (1832-1837), known as "the man of the laws".

- Juan Manuel Santos - President of Colombia (2010-2018) and Nobel prize winner

- Antanas Mockus - former Bogota mayor (Lithuanian ancestry).

Singers

- Juanes - musician (Basque ancestry).[16]

- Andrés Mercado - singer.

- Shakira - singer (Lebanese, Spanish and Italian ancestry).

- Sebastián Yatra - singer.

Arts and entertainment

- Manolo Cardona - actor

- María Helena Doering - actress (German ancestry)

- Juan Pablo Gamboa - actor (British American ancestry)

- Aura Cristina Geithner - actress and model (German ancestry)

- Diana Golden - telenovela actress

- Miguel Gómez - photographer (Spanish and French ancestry)

- Mauricio Henao - actor

- Natasha Klauss - actress (German ancestry)

- Kristina Lilley - American-born, Colombian-raised actress (European-American and Norwegian ancestry)

- Maritza Rodríguez - actress

- Victor Mallarino - actor

- Isabella Santo Domingo - actress

- Silvia Tcherassi - fashion designer (Italian ancestry)

- Geraldine Zivic - Argentine-born, Colombian-raised actress (Serbian ancestry)

Writers

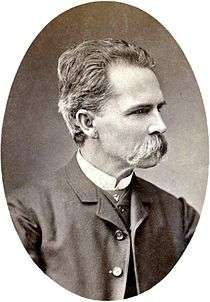

- Rufino José Cuervo - writer.

- Jorge Isaacs - writer and politician.

- Nicolás Gómez Dávila - writer (Spanish roots).

- Rafael Pombo - writer.

- José Asunción Silva - poet.

- Sergio Esteban Vélez - journalist (Spanish ancestry).

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez - writer and Nobel prize winner

Others

- Rodolfo Llinás - neuroscientist.

See also

References

- "Contador de Poblacion". Dane.gov.co. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- Bushnell, David; Hudson, Rex A. (2010). "The Society and Its Environment" (PDF). In Rex A. Hudson (ed.). Colombia: a country study. Washington, D.C: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 87, 92. ISBN 978-0-8444-9502-6.

- Schwartzman, Simon. "Etnia, condiciones de vida y discrimacion" (PDF). Schwartzman.org.br. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- Lizcano Fernández, Francisco (2005). "Composición Étnica de las Tres Áreas Culturales del Continente Americano al Comienzo del Siglo XXI" [Ethnic Composition of Three Cultural Areas of the Americas at Beginning of the XXI Century] (PDF). Convergencia (in Spanish). 38 (May–August): 185–232. ISSN 1405-1435. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2008: see table on page 218

- Bushnell & Hudson, p. 87-88.

- Possible paradises: Basque emigration to Latin America by José Manuel Azcona Pastor, P.203

- Amerikanuak: Basques in the New World by William A. Douglass, Jon Bilbao, P.167

- Jim Watson. "SCADTA Joins the Fight". Stampnotes.com. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- Latin America during World War II by Thomas M. Leonard, John F. Bratzel, P.117

- "'Lost Jews' Of Colombia Say They've Found Their Roots". npr.org. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- Wasko, Dennis (13 June 2011). "The Jewish Palate: The Jews of Colombia - Arts & Culture - Jerusalem Post". Jpost.com. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- de Posada, Louise Fawcett; Eduardo Posada-Carbó (1992). "En la tierra de las oportunidades: los sirio-libaneses en Colombia" [In the land of opportunity: the Syrian-Lebanese in Colombia]. Boletín Cultural y Bibliográfico (in Spanish). XXIX (29). Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- Fawcett, Louise; Posada‐Carbo, Eduardo (21 June 2010). "Arabs and Jews in the development of the Colombian Caribbean 1850–1950". Immigrants & Minorities. 16 (1–2): 57–79. doi:10.1080/02619288.1997.9974903.

- "Agência de Notícias Brasil-Árabe". .anba.com.br. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- Beltrán Cely, William Mauricio. "Descripción cuantitativa de la pluralización religiosa en Colombia" (PDF). Bdigital.unal.edu.co.

- Mingo, Enrique (24 October 2012). "Juanes encuentra sus raíces" [Juanes finds his roots] (in Spanish). Diariovasco.com. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

Works cited

- Bushnell, David and Rex A. Hudson. "Racial distinctions". In Colombia: A Country Study (Rex A. Hudson, ed.). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (2010).

.jpg)