Warfare in pre-colonial Philippines

Warfare in pre-colonial Philippines refers to the military history of the Philippines prior to Spanish colonization.

| Sandatahang Lakas Armed forces | |

|---|---|

Kampilan sword on display | |

| Active | c. 900 – 1576 |

| Country | Various (Philippine archipelago) |

| Branch | Palace guards Capital Defense Artillery Corps Cavalry Corps Infantry Regiments Navy |

| Type | Army, Navy |

| Role | Military force |

| Part of | Feudal |

| Garrison/HQ | Tondo Kuta Selurong Kalibo Singhapala Kota wato Kota Sug |

| Engagements | Expeditions Majapahit-Luzon conflict[1] Chinese piracy Bruneian Invasion[2] Burmese–Siamese War (1547–49) Battle of Mactan Spanish Conquest |

| Decorations | Batikan[3] |

| Battle honours | Gold Slaves[4] |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Various Datu's, Hari, Rajah's and Sultans |

Background

In the Pre-Colonial era, the Philippine people had their own forces, divided between the islands, each one with its own ruler. These forces were called Sandigs ("Guards"), Kawal ("Knights"), and Tanods. As well as military operations, the forces provided policing and coastal watching functions.

Tactics and Strategies

Participating in land and sea raids were an essential part of the duties of the timawa. These raids are usually regular annual expeditions undertaken by the community (similar to the Vikings) against enemies and enemies of their allies. Participation and conduct in raids and other battles were recorded permanently by the timawa and the tumao in the form of tattoos on their bodies, hence the Spanish name for them - pintados (literally "the painted ones"). Another strategy used throughout the islands were ambushes where they would lead large enemy troops into an ambush of surrounding men or attacking enemies from behind when their defenses are down. The Spanish conquistador Miguel de Loarca described the preparations and the undertaking of such raids in his book Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (1582).[5]

Scorched earth tactics

The Rajahnate of Cebu fought against the Moro pirates, known as magalos (literally "destroyers of peace"), from Mindanao.[6] The islands the rajahnate was in, were collectively known as Pulua Kang Dayang or Kangdaya (literally "[the islands] which belong to Daya").

Sri Lumay was noted for his strict policies in defending against Moro raiders and slavers from Mindanao. His use of scorched earth tactics to repel invaders gave rise to the name Kang Sri Lumayng Sugbo (literally "that of Sri Lumay's great fire") to the town, which was later shortened to Sugbo ("scorched earth").

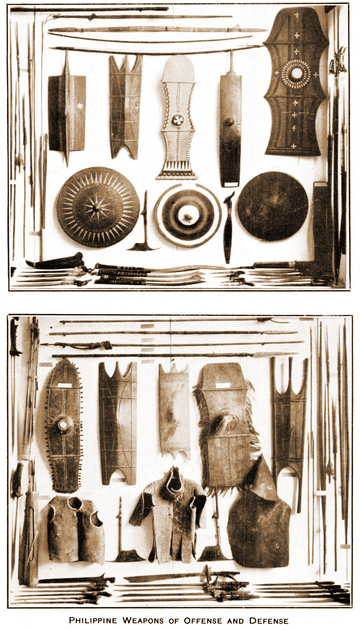

Military technology

Infantry

The making of swords involved elaborate rituals that were based mainly on the auspicious conjunctions of planets. The passage of the sword from the maker entailed a mystical ceremony that was coupled with beliefs. The lowlanders of Luzon no longer used the bararao, while the Moros and animists of the South still continue the tradition of making kampilan and kris.[7] Swords (kalis and kampilan) were either straight or wavy double-edged, with bronze or iron blades and hilts made of hardwoods, bone, antler, shell, or, for high ranking individuals, gold encrusted with precious stones. Firearms in the form of matchlock arquebuses were also locally manufactured and used by the natives.[8][9] The most fearsome among these native guns was the lantaka, which were portable handheld cannons.[10][7]

Artillery

Ancient peoples also used larger cannons made of iron and resembling culverins that provided heavier firepower. They were sometimes mounted on a boat or fortification that can be wheeled, allowing the gunner to quickly track a moving target.[7] The iron cannon at Rajah Sulayman's house was about 17 feet long and was made out of clay and wax moulds.[7]

Fortifications

Ancient Filipinos built strong fortresses called kota or moog to protect their communities. The Moros, in particular, had armor that covered the entire body from the top of the head to the toes. The Igorots built forts made of stone walls that averaged several meters in width and about two to three times the width in height around 2000 BC.[7] Spanish descriptions indicate that the typical fortifications consisted of raised earthworks with a wooden palisade along the top (called a "kuta" in Tagalog) surrounded by a ditch or water-filled moat. However, local variations on construction technique were specific to the local environment. In Bicol, bamboo towers called "bantara" were built behind the fortifications as a stand for archers armed with long bows. There are reports of well constructed wooden fortifications around the political centers of Manila, Tondo, Cebu, Mindoro and numerous other coastal towns.

The Ivatan people of the northern islands of Batanes often built fortifications to protect themselves during times of war. They built their so-called idjangs on hills and elevated areas.[11] These fortifications were likened to European castles because of their purpose. Usually, the only entrance to the castles would be via a rope ladder that would only be lowered for the villagers and could be kept away when invaders arrived.

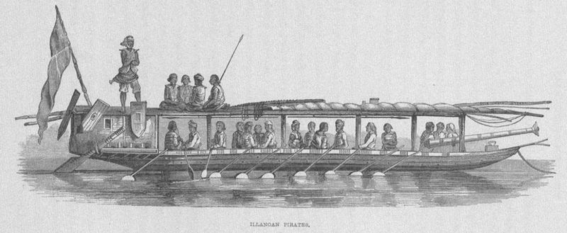

Naval technologies

The Karakowa

Philippine ships, such as the karakao or korkoa, were of excellent quality and some of them were used by the Spaniards in expeditions against rebellious tribes and Dutch and British forces. Some of the larger rowed vessels held up to a hundred rowers on each side besides a contingent of armed troops. Generally, the larger vessels held at least one lantaka at the front of the vessel or another one placed at the stern.[7] Philippine sailing ships called praos had double sails that seemed to rise well over a hundred feet from the surface of the water. Despite their large size, these ships had double outriggers. Some of the larger sailing ships, however, did not have outriggers.[12]

Uniforms/Clothing

Precolonial Filipinos made excellent armor for use on the battlefield, and swords were an important part of native weaponry. In some parts of the Philippines, armor was made from diverse materials such as cordage, bamboo, tree bark, sharkskin, and water buffalo hide to deflect piercing blows by cutlasses or spear points. Visayan chainmail and cuirasses were called barote: quilted or corded body armor. Spaniards called these "escaupiles", after the cotton-padded exemplars they found in the New World. The barote was woven of thick braided Abacá or bark cords, tight enough to be waterproof and knotted intricately so that cuts did not spread. Burlap was worn against the body under the barote; the body armor itself extended to the elbow and knee with an ankle-length variety with sleeves for manning defenses, although for greater agility confident warriors preferred to go without them. "Pakil" and "batung-batung" were breastplates and back plates made of bamboo bark, hardwood like ebony or in Mindanao, and caraboa horn or elephant hide from Jolo. Sharkskin was used effectively for helmets or "moriones". Shields were important defensive weapons in all lowland societies of the Philippines. Visayan shields, kalasag, were made of light, fibrous wood designed to enmesh any spear or dagger that penetrated its surface and to prevent their retrieval by the enemy. Shields were strengthened and decorated with an elaborate rattan binding on the front, which was also coated with a resin that turned rock-hard upon drying. These shields were generally 0.5 meters by 1.5 meters in size and, along with missile deflecting helmets, provided full body protection that was difficult to penetrate. Thus, it is not surprising that most of the raids that were successful in terms of taking captives and heads, were surprise ambushes that literally caught the enemy with his shields down.

Historical incidents

Between 1174 and 1190 CE, Chau Ju-Kua, a travelling Chinese government bureaucrat, reported a group of "ferocious raiders" near the coast of Fujian. Chau called them Pishoye and believed they were from the south of Taiwan (Formosa).[14]

In 1365 CE, the Battle of Manila took place between the a kingdom of Luzon and the Empire of Majapahit. According to the Nagarakretagama (1365), Majapahit conquered Saludong (the Majapahit term for Luzon and Manila).[15]

in the 1500s, the people of Luzon were called the Luções. They gained power in their region through effective trade and through military campaigns in Myanmar, Malacca and East Timor.[16][17]

where Lucoes were employed as traders and mercenaries.[18][18]

In 1547 CE, Luções warriors supported the Burmese king in his invasion of Siam. At the same time, Lusung warriors fought with the Siamese king against the elephant army of the Burmese king in the defence of the Siamese capital at Ayuthaya, where they were employed as traders and mercenaries.[19][20]

In 1521, the Visayan king of Mactan, Lapu-Lapu in Cebu organized the first recorded military action against the Spanish colonizers in the Battle of Mactan.[21]

The former sultan of Malacca decided to retake his city from the Portuguese with a fleet of ships from Lusung in 1525 AD.[16] Lucoes (warriors from Luzon) aided the Burmese king in his invasion of Siam in 1547 AD. At the same time, Lusung warriors fought alongside the Siamese king and faced the same elephant army of the Burmese king in the defence of the Siamese capital at Ayuthaya.[22]

See also

- History of the Philippines

- History of the Philippines (900–1521)

- Armed Forces of the Philippines

- Philippine Revolutionary Army

- Burmese–Siamese War

- Cultural achievements of pre-colonial Philippines

- Maharlika

- Timawa

- Juramentado

- List of wars involving the Philippines

- List of conflicts in the Philippines

- Battle of the Philippines

References

- Myron (1939). "The Study of The Artistic Antiquities of Dutch India". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. Harvard-Yenching Institute. 4 (1): 59–68. doi:10.2307/2717905. JSTOR 2717905.

- del Mundo, Clodualdo (September 20, 1999). "Ako'y Si Ragam (I am Ragam)". Diwang Kayumanggi. Archived from the original on October 25, 2009. Retrieved 2008-09-30.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- G. Nye Steiger, H. Otley Beyer, Conrado Benitez, A History of the Orient, Oxford: 1929, Ginn and Company, pp. 122-123.

- Blair, Emma Helen (August 25, 2004). The Philippine Islands. The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803, Volume II, 1521-1569, by Emma Helen Blair. p. 126, Volume II.

- Emma Helen Blair; James Alex; er Robertson, eds. (1903). "Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (1582) by Miguel de Loarca". The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803, Volume V., 1582-1583: Explorations By Early Navigators, Descriptions Of The Islands And Their Peoples, Their History And Records Of The Catholic Missions, As Related In Contemporaneous Books And Manuscripts, Showing The Political, Economic, Commercial And Religious Conditions Of Those Islands From Their Earliest Relations With European Nations To The Beginning Of The Nineteenth Century. The A.H. Clark Company (republished online by Project Gutenberg).

- Marivir Montebon, Retracing Our Roots – A Journey into Cebu’s Pre-Colonial Past, p.15

- Ancient and Pre-Spanis Era of the Philippines. Accessed September 04, 2008.

- "10 Reasons Why Life Was Better In Pre-Colonial Philippines". Filipiknow. October 7, 2018

- Barrows, David P., Ph.D. "THE FILIPINO PEOPLE BEFORE THE ARRIVAL OF THE SPANIARDS". Artes Delas Filipinas.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) October 7, 2018

- FILIPINO BLADE CULTURE AND THE ADVENT OF FIREARMS

- "15 Most Intense Archaeological Discoveries in Philippine History". FilipiKnow. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- It was integrated to the Spanish Empire through pacts and treaties (c.1569) by Miguel López de Legazpi and his grandson Juan de Salcedo. During the time of their hispanization, the principalities of the Confederation were already developed settlements with distinct social structure, culture, customs, and religion.

- Herbert W. Krieger (1899). The Collection of Primitive Weapons and Armor of the Philippine Islands in the United States National Museum. Smithsonian Institution - United States National Museum - Bulletin 137. Washington: Government Printing Office.

- Bersales J. "raiding China" Inquirer website 6 June 2013. Accessed 7 August 2017.

- Malkiel-Jirmounsky M. "The Study of the Artistic Antiquities of Dutch India" Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Harvard-Yenching Institute 1939 4:1 p. 59 – 68. doi:10.2307/2717905 JSTOR 2717905

- The former sultan of Malacca decided to retake his city from the Portuguese with a fleet of ships from Lusung in 1525 A.D., SOURCE: Barros, Joao de, Decada terciera de Asia de Ioano de Barros dos feitos que os Portugueses fezarao no descubrimiento dos mares e terras de Oriente [1628], Lisbon, 1777, courtesy of William Henry Scott, Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1994, page 194.

- Pigafetta, Antonio (1969) [1524]. "First voyage round the world". Translated by J.A. Robertson. Manila: Filipiniana Book Guild. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Reid, Anthony (1995). "Continuity and Change in the Austronesian Transition to Islam and Christianity". In Peter Bellwood; James J. Fox; Darrell Tryon (eds.). The Austronesians: Historical and comparative perspectives. Canberra: Department of Anthropology, The Australian National University.

- Pires, Tomé (1944). Armando Cortesao (translator) (ed.). A suma oriental de Tomé Pires e o livro de Francisco Rodriguez: Leitura e notas de Armando Cortesão [1512 - 1515] (in Portuguese). Cambridge: Hakluyt Society.

- Lach, Donald Frederick (1994). "Chapter 8: The Philippine Islands". Asia in the Making of Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-46732-5.

- "The Death of Magellan, 1521" Eyewitness to History website Accessed 3 August 2017

- Lucoes warriors aided the Burmese king in his invasion of Siam in 1547 AD. At the same time, Lusung warriors fought alongside the Siamese king and faced the same elephant army of the Burmese king in the defence of the Siamese capital at Ayuthaya.

_01.jpg)