Video game crash of 1983

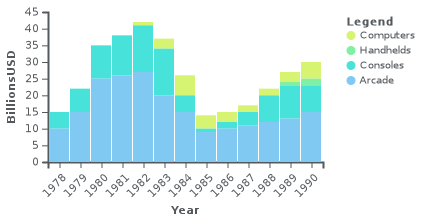

The video game crash of 1983 (known as the Atari shock in Japan) was a large-scale recession in the video game industry that occurred from 1983 to 1985, primarily in the United States. The crash was attributed to several factors, including market saturation in the number of game consoles and available games, and waning interest in console games in favor of personal computers. Revenues peaked at around $3.2 billion in 1983, then fell to around $100 million by 1985 (a drop of almost 97 percent). The crash abruptly ended what is retrospectively considered the second generation of console video gaming in North America.

| Part of a series on the |

| History of video games |

|---|

Lasting about two years, the crash shook the then-booming industry, and led to the bankruptcy of several companies producing home computers and video game consoles in the region. Analysts of the time expressed doubts about the long-term viability of video game consoles and software.

The North American video game console industry eventually recovered a few years later, mostly due to the widespread success of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in 1986; Nintendo designed the NES as the Western branding for its Famicom console originally released in 1983 in order to avoid the missteps which caused the 1983 crash and avoid the stigma which video games had at that time.

Causes and factors

Flooded console market

The Atari Video Computer System (renamed the Atari 2600 in late 1982) was not the first home system with swappable game cartridges, but by the early 1980s was the most popular second generation console by a wide margin. The Atari VCS was launched in 1977 with modest sales for its first few years. In 1980, Atari's licensed version of Space Invaders from Taito became the console's killer application; sales of the VCS quadrupled, and the game was the first title to sell more than a million copies.[1][2] Spurred by the success of the Atari VCS, other consoles were introduced, both from Atari and other companies: Odyssey², Intellivision, ColecoVision, Atari 5200, and Vectrex. Coleco sold an add-on allowing Atari 2600 games to be played on its ColecoVision.

Each of the new consoles had its own library of games produced by the console maker, and the Atari 2600 had a large library of games produced by third-party developers. In 1982, analysts noticed trends of saturation, mentioning that the amount of new software coming in will only allow a few big hits, that retailers had too much floor space for systems, and that price drops for home computers could result in an industry shakeup.[3]

In addition, the rapid growth of the video game industry led to an increased demand for video games, but which the manufacturers over-projected. An analyst for Goldman Sachs stated in 1983 that the demand for video games was up 100% from 1982, but the manufacturing output increased by 175%, creating a surplus in the market. Raymond Kassar, the CEO of Atari, recognized in 1982 that there would become a point of saturation for the industry, but did not expect this to occur until about half of American households had a video game console; the crash occurred when about 15 million machines had been sold, below this expected point.[4]

Loss of publishing control

Prior to 1979, there were no third-party developers; console manufacturers like Atari made their own games for their own systems. This changed with the formation of Activision in 1979.[5] Activision was founded by four Atari programmers who left the company because Atari did not allow credits to appear on their games and did not pay employees a royalty based on sales. At the time, Atari was owned by Warner Communications, and the developers felt that they should receive the same recognition that musicians, directors, and actors got from Warner's other divisions. The four programmers, having knowledge of the Atari VCS system already, were able to build on that to develop their own games and cartridge manufacturing processes. After Activision went into business, Atari quickly sued to block sales of Activision's products, but failed to secure a restraining order and ultimately settled the case in 1982, with Activision agreeing to pay royalties to Atari but otherwise legitimizing the third-party model.[6] Activision games were as popular as Atari's, with Pitfall! in 1982 drawing over four million units sold.[7]

A small number of third-party developers came in the footsteps of Activision prior to 1982, including Imagic, Games by Apollo, Coleco, Parker Brothers, CBS Video Games, and Mattel for the Atari VCS. By 1982, Activision's success led numerous companies to try to follow in Activision's wake. However, Activision's founder David Crane observed that several of these companies were led from venture capitalists with a number of fresh computer programmers lacking experience, attempting to capture the same success as Activision, not only for the Atari VCS but on other consoles. Without the experience that Crane and his team had, many of these games were of poor quality,[7] with Crane describing them as "the worst games you can imagine".[8] Companies lured away each other's programmers or used reverse engineering to learn how to make games for proprietary systems. Atari even hired several programmers from Mattel's Intellivision development studio, prompting a lawsuit by Mattel against Atari that included charges of industrial espionage.

The rapid growth of the third-party game industry was evident by the number of vendors present at the semi-annual Consumer Electronics Show (CES). Crane recalled that during the six months between two consecutive CES events, the number of third-party developers jumped from 3 to 30.[8] At the Summer 1982 CES there were 17 companies, including MCA Inc., and Fox Video Games announced 90 new Atari games.[9] By 1983, an estimated 100 companies were vying to get a foothold in the video game market via the CES.[4] In the second half of 1982 the number of cartridges grew from 100 in June to more than 400 in December.[5]

Experts predicted a glut in 1983, with 10% of games producing 75% of sales.[5] BYTE stated in December that "in 1982 few games broke new ground in either design or format ... If the public really likes an idea, it is milked for all it's worth, and numerous clones of a different color soon crowd the shelves. That is, until the public stops buying or something better comes along. Companies who believe that microcomputer games are the hula hoop of the 1980s only want to play Quick Profit."[10] Bill Kunkel said in January 1983 that companies had "licensed everything that moves, walks, crawls, or tunnels beneath the earth. You have to wonder how tenuous the connection will be between the game and the movie Marathon Man. What are you going to do, present a video game root canal?"[11] By September 1983 the Phoenix stated that 2600 cartridges "is no longer a growth industry".[12] Activision, Atari, and Mattel all had experienced programmers, but many of the new companies rushing to join the market did not have the expertise or talent to create quality games. Titles such as Ralston Purina's dog food-themed Chase the Chuckwagon, the Kaboom!-like Lost Luggage, rock band tie-in Journey Escape, and plate-spinning game Dishaster, were examples of games made in the hopes of taking advantage of the video-game boom, but later proved unsuccessful with retailers and potential customers.

Competition from home computers

In 1979, Atari unveiled the Atari 400 and 800 computers, built around a chipset originally meant for use in a game console, and which retailed for the same price as their respective names. In 1981, IBM introduced the IBM 5150 PC with a $1,565 base price[13] (equivalent to $4,401 in 2019), while Sinclair Research introduced its low-end ZX81 microcomputer for £70 (equivalent to £270 in 2019). By 1982, new desktop computer designs were commonly providing better color graphics and sound than game consoles and personal computer sales were booming. The TI 99/4A and the Atari 400 were both at $349 (equivalent to $925 in 2019), the Tandy Color Computer sold at $379 (equivalent to $1,004 in 2019), and Commodore International had just reduced the price of the VIC-20 to $199 (equivalent to $527 in 2019) and the C64 to $499 (equivalent to $1,322 in 2019).[14][15]

Because computers generally had more memory and faster processors than a console, they permitted more sophisticated games. A 1984 compendium of reviews of Atari 8-bit software used 198 pages for games compared to 167 for all other software types.[16] Home computers could also be used for tasks such as word processing and home accounting. Games were easier to distribute, since they could be sold on floppy disks or Compact Cassettes instead of ROM cartridges. This opened the field to a cottage industry of third-party software developers. Writeable storage media allowed players to save games in progress, a useful feature for increasingly complex games which was not available on the consoles of the era.

In 1982, a price war that began between Commodore and Texas Instruments led to home computers becoming as inexpensive as video-game consoles;[17] after Commodore cut the retail price of the 64 to $300 in June 1983, some stores began selling it for as little as $199.[12] Dan Gutman, founder in 1982 of Video Games Player magazine, recalled in 1987 that "People asked themselves, 'Why should I buy a video game system when I can buy a computer that will play games and do so much more?'"[18] The Boston Phoenix stated in September 1983 about the cancellation of the Intellivision III, "Who was going to pay $200-plus for a machine that could only play games?"[12] Commodore explicitly targeted video game players. Spokesman William Shatner asked in VIC-20 commercials "Why buy just a video game from Atari or Intellivision?", stating that "unlike games, it has a real computer keyboard" yet "plays great games too".[19] Commodore's ownership of chip fabricator MOS Technology allowed manufacture of integrated circuits in-house, so the VIC-20 and C64 sold for much lower prices than competing home computers.

"I've been in retailing 30 years and I have never seen any category of goods get on a self-destruct pattern like this", a Service Merchandise executive told The New York Times in June 1983.[17] The price war was so severe that in September Coleco CEO Arnold Greenberg welcomed rumors of an IBM 'Peanut' home computer because although IBM was a competitor, it "is a company that knows how to make money". "I look back a year or two in the videogame field, or the home-computer field", Greenberg added, "how much better everyone was, when most people were making money, rather than very few".[20] Companies reduced production in the middle of the year because of weak demand even as prices remained low, causing shortages as sales suddenly rose during the Christmas season;[21] only the Commodore 64 was widely available, with an estimated more than 500,000 computers sold during Christmas.[22] The 99/4A was such a disaster for TI, that the company's stock immediately rose by 25% after the company discontinued it and exited the home-computer market in late 1983.[23] JC Penney announced in December 1983 that it would soon no longer sell home computers, because of the combination of low supply and low prices.[24]

By that year, Gutman wrote, "Video games were officially dead and computers were hot". He renamed his magazine Computer Games in October 1983, but "I noticed that the word games became a dirty word in the press. We started replacing it with simulations as often as possible". Soon "The computer slump began ... Suddenly, everyone was saying that the home computer was a fad, just another hula hoop". Computer Games published its last issue in late 1984.[18] In 1988, Computer Gaming World founder Russell Sipe noted that "the arcade game crash of 1984 took down the majority of the computer game magazines with it." He stated that, by "the winter of 1984, only a few computer game magazines remained," and by the summer of 1985, Computer Gaming World "was the only 4-color computer game magazine left."[25]

Inflation

The U.S. game industry lobbied in Washington, D.C. for a smaller $1 coin, closer to the size of a quarter, arguing that inflation (which had reduced the quarter's spending power by a third in the early 1980s) was making it difficult to prosper.[26] During the 1970s, the dollar coin in use was the Eisenhower dollar, a large coin impractical for vending machines. The Susan B. Anthony dollar was introduced in 1979, and its size fit the video game manufacturers' demands, but it was a failure with the general public. Ironically, the new coin's similarity to the quarter was one of the most common complaints.

Arcade machines in Japan had standardized the use of ¥100 coins, worth roughly $1, which industry veteran Mark Cerny proposed as a reason for the stability of the game industry in Japan.[26]

Result

Immediate effects

The release of so many new games in 1982 flooded the market. Most stores had insufficient space to carry new games and consoles. As stores tried to return the surplus games to the new publishers, the publishers had neither new products nor cash to issue refunds to the retailers. Many publishers, including Games by Apollo[27] and US Games,[28] quickly folded. Unable to return the unsold games to defunct publishers, stores marked down the titles and placed them in discount bins and sale tables. Recently released games which initially sold for US$35 (equivalent to $92 in 2018) were in bins for $5 ($13 in 2018).[28][29]

The presence of third-party sales drew the market share that the console manufacturers had. Atari's share of the cartridge-game market fell from 75% in 1981 to less than 40% in 1982, which negatively affected their finances.[30] The bargain sales of poor-quality titles further drew sales away from the more successful third-party companies like Activision due to uneducated consumers being drawn by price to purchase the bargain titles rather than quality. By June 1983, the market for the more expensive games had shrunk dramatically and was replaced by a new market of rushed-to-market, low-budget games.[7] Crane said that "those awful games flooded the market at huge discounts, and ruined the video game business".[8]

A massive industry shakeout resulted. Magnavox abandoned the video game business entirely. Imagic withdrew its IPO the day before its stock was to go public; the company later collapsed. Activision, to stay competitive and maintain financial security, began development of games for the personal computer. Within a few years, Activision no longer produced cartridge-based games and focused solely on personal computer games.[7]

.jpg)

One of the more predominant effects of the 1983 crash was on Atari. In 1982, it had published large volumes of Atari 2600 games that it had expected to sell well, including a port of Pac-Man and game adaption of the film E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. However, due to the quality of these games and other market factors, much of Atari's production did not get sold. In September 1983, Atari discreetly buried much of this excess stock, as well as unsold stock of earlier games, in a landfill near Alamogordo, New Mexico, though Atari did not comment about their activity at the time. Misinformation related to sales of Pac-Man and E.T. led to an urban legend of the Atari video game burial that millions of unsold cartridges were buried there. Gaming historians received permission to dig up the landfill as part of a documentary in 2014, during which former Atari executives clarified that only about 700,000 cartridges had been buried in 1982, backed by estimates made during the excavation, and disproving the scale of the urban legend. Despite this, Atari's burial remains an iconic representation of the 1983 video game crash.[31][32][33]

As a result, while some stores sold new games and machines, most retailers stopped selling video game consoles or reduced their stock significantly, reserving floor or shelf space for other products. This was the most formidable barrier that confronted Nintendo, as it tried to market its Famicom system in the United States. Retailer opposition to video games was directly responsible for causing Nintendo to brand its product an "Entertainment System" rather than a "console", using terms such as "control deck" and "Game Pak", as well as producing a toy robot called R.O.B. to convince toy retailers to allow it in their stores. Furthermore, the design for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) used a front-loading cartridge slot to mimic how video cassette recorders, popular at that time, were loaded, further pulling the NES away from previous console designs.[34][35][36]

The crash also affected video game arcades. While the number of arcades in the United States had doubled to 10,000 from 1980 to 1982, the crash led to a closure of around 1,500 arcades, and revenues of those that remained open had fallen by 40%.[4]

The full effects of the industry crash would not be felt until 1985.[37] Despite Atari's claim of 1 million in sales of its 2600 game system that year,[38] recovery was slow. The sales of home video games had dropped from $3.2 billion in 1982[39] to $100 million in 1985.[40] Analysts doubted the long-term viability of the video game industry,[41] but following the release of the Nintendo Entertainment System, the industry began recovering, with annual sales exceeding $2.3 billion by 1988, with 70% of the market dominated by Nintendo.[42] In 1986, Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi noted that "Atari collapsed because they gave too much freedom to third-party developers and the market was swamped with rubbish games". In response, Nintendo limited the number of titles that third-party developers could release for their system each year, and promoted its "Seal of Quality", which it allowed to be used on games and peripherals by publishers that met Nintendo's quality standards.[43]

The end of the crash allowed Commodore to raise the price of the C64 for the first time upon the June 1986 introduction of the Commodore 64c—a Commodore 64 redesigned for lower cost of manufacture—which Compute! cited as the end of the home-computer price war,[44][45] one of the causes of the crash.[46]

Long-term effects

The crash in 1983 had a significant impact on all sectors of the global video game market worldwide, and took several years to recover. The estimated US$42 billion market in 1982, including consoles, arcade, and personal computer games, dropped to US$14 billion by 1985, with a significant shift away from arcades and consoles to personal computer software in the years that followed.[47]

Japanese dominance

The North American video game crash had two long-lasting results. The first result was that dominance in the home console market shifted from the United States to Japan. The crash did not directly affect the financial viability of the video game market in Japan, but it still came as a surprise there and created repercussions that changed that industry, and thus became known as the "Atari shock".[48]

As the crash was happening in the United States, Japan's game industry started to shift its attention from arcade games to home consoles. Within one month in 1983, three new home consoles were released in Japan: the Nintendo Famicom (two years later released in Western markets as Nintendo Entertainment System (NES)), Sega's SG-1000, and Microsoft Japan's MSX hybrid computer-console system, all heralding the third generation of home consoles.[49] These three consoles were extremely popular, buoyed by an economic bubble in Japan. The units readily outsold Atari and Mattel's existing systems, and with both Atari and Mattel focusing on recovering domestic sales, the Japanese consoles effectively went uncontested over the next few years.[49] By 1986, three years after its introduction, 6.5 million Japanese homes—19% of the population—owned a Famicom, and Nintendo began exporting it to the U.S., where the home console industry was only just recovering from the crash.[43] By 1987 the Nintendo Entertainment System was very popular in North America.[50]

By the time the U.S. video game market recovered in the late 1980s, the NES was by far the dominant console in the United States, leaving only a fraction of the market to a resurgent Atari. By 1989, home video game sales in the United States had reached $5 billion, surpassing the 1982 peak of $3 billion during the previous generation. A large majority of the market was controlled by Nintendo; it sold more than 35 million units in the United States, exceeding the sales of other consoles and personal computers by a considerable margin.[51] Other Japanese companies also rivaled Nintendo's success in the United States, with Sega's Mega Drive/Genesis in 1989 and NEC's PC Engine/TurboGrafx 16 released the same year.

Impact on third-party software development

A second, highly visible result of the crash was the advancement of measures to control third-party development of software. Using secrecy to combat industrial espionage had failed to stop rival companies from reverse engineering the Mattel and Atari systems and hiring away their trained game programmers. While Mattel and Coleco implemented lockout measures to control third-party development (the ColecoVision BIOS checked for a copyright string on power-up), the Atari 2600 was completely unprotected and once information on its hardware became available, little prevented anyone from making games for the system. Nintendo thus instituted a strict licensing policy for the NES that included equipping the cartridge and console with lockout chips, which were region-specific, and had to match in order for a game to work. In addition to preventing the use of unlicensed games, it also was designed to combat software piracy, rarely a problem in the United States or Western Europe, but rampant in East Asia.

Accolade achieved a technical victory in one court case against Sega, challenging this control, even though it ultimately yielded and signed the Sega licensing agreement. Several publishers, notably Tengen (Atari), Color Dreams, and Camerica, challenged Nintendo's control system during the 8-bit era by producing unlicensed NES games. The concepts of such a control system remain in use on every major video game console produced today, even with fewer "cartridge-based" consoles on the market than in the 8/16-bit era. Replacing the security chips in most modern consoles are specially encoded optical discs that cannot be copied by most users and can only be read by a particular console under normal circumstances.

Nintendo limited most third-party publishers to only five games per year on its systems (some companies tried to get around this by creating additional company labels like Konami's Ultra Games label); Nintendo would ultimately drop this rule by 1993 with the release of the Super Nintendo Entertainment System.[52] It also required all cartridges to be manufactured by Nintendo, and to be paid for in full before they were manufactured. Cartridges could not be returned to Nintendo, so publishers assumed all the financial risk of selling all units ordered. As a result, some publishers lost more money due to distress sales of remaining inventory at the end of the NES era than they ever earned in profits from sales of the games.

Nintendo portrayed these measures as intended to protect the public against poor-quality games, and placed a golden seal of approval on all licensed games released for the system. Further, Nintendo implemented its proprietary 10NES, a lockout chip which was designed to prevent cartridges made without the chip from being played on the NES. The 10NES lockout was not perfect, as later in the NES's lifecycle methods were found to bypass it, but it did sufficiently allow Nintendo to strengthen its publishing control to avoid the mistakes Atari had made.[53] These strict licensing measures backfired somewhat after Nintendo was accused of antitrust behavior.[54] In the long run, this pushed many western third-party publishers such as Electronic Arts away from Nintendo consoles, and would actively support competing consoles such as the Sega Genesis or Sony PlayStation. Most of the Nintendo platform-control measures were adopted by later console manufacturers such as Sega, Sony, and Microsoft, although not as stringently.

Computer game growth

With waning console interests in the United States, the computer game market was able to gain a strong foothold in 1983 and beyond.[49] Developers that had been primarily in the console games space, like Activision, turned their attention to developing computer game titles to stay viable.[49] Newer companies also were founded to capture the growing interest in the computer games space with novel elements that borrowed from console games, as well as taking advantage of low-cost dial-up modems that allowed for multiplayer capabilities.[49]

References

- Kent, Steven (2001). Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. p. 190. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- Weiss, Brett (2007). Classic home video games, 1972–1984: a complete reference guide. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7864-3226-4.

- Jones, Robert S. (Dec 12, 1982). "Home Video Games Are Coming Under a Strong Attack". Gainesville Sun. Retrieved from https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1320&dat=19821212&id=L2tWAAAAIBAJ&sjid=q-kDAAAAIBAJ&pg=1609,4274079&hl=en

- Kleinfield, N.R. (October 17, 1983). "Video Games Industry Comes Down To Earth". The New York Times. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- "Stream of video games is endless". Milwaukee Journal. December 26, 1982. pp. Business 1. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- Beller, Peter C. (February 2, 2009). "Activision's Unlikely Hero". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017.

- Flemming, Jeffrey. "The History Of Activision". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- Adrian (May 9, 2016). "INTERVIEW – DAVID CRANE (ATARI/ACTIVISION/SKYWORKS)". Arcade Attack. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- Goodman, Danny (Spring 1983). "Home Video Games: Video Games Update". Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games. p. 32. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017.

- Clark, Pamela (December 1982). "The Play's the Thing". BYTE. p. 6. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- Harmetz, Aljean (January 15, 1983). "New Faces, More Profits For Video Games". Times-Union. p. 18. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- Mitchell, Peter W. (September 6, 1983). "A summer-CES report". Boston Phoenix. p. 4. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- "IBM Archives: The birth of the IBM PC". January 23, 2003. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014.

- Ahl, David H. (1984 November). The first decade of personal computing Archived December 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Creative Computing, vol. 10, no. 11: p. 30.

- "The Inflation Calculator". Archived from the original on March 26, 2018.

- Stanton, Jeffrey; Wells, Robert P.; Rochowansky, Sandra; Mellin, Michael. The Addison-Wesley Book of Atari Software 1984. Addison-Wesley. pp. TOC. ISBN 020116454X.

- Pollack, Andrew (June 19, 1983). "The Coming Crisis in Home Computers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 20, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- Gutman, Dan (December 1987). "The Fall And Rise of Computer Games". Compute!'s Apple Applications. p. 64. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- Commodore VIC-20 ad with William Shatner. June 9, 2010. Archived from the original on April 6, 2017.

- Coleco Presents The Adam Computer System. YouTube. May 3, 2016 [1983-09-28]. Event occurs at 1:06:55. Archived from the original on January 3, 2017.

IBM is just not another strong company making a positive statement about the home-computer field's future. IBM is a company that knows how to make money. IBM is a company that knows how to make money in hardware, and makes more money in software. What IBM can bring to the home-computer field is something that the field collectively needs, particularly now: A respect for profitability. A capability to earn money. That is precisely what the field needs ... I look back a year or two in the videogame field, or the home-computer field, how much better everyone was, when most people were making money, rather than very few were making money.

- Rosenberg, Ronald (December 8, 1983). "Home Computer? Maybe Next Year". The Boston Globe.

- "Under 1983 Christmas Tree, Expect the Home Computer". The New York Times. December 10, 1983. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- "IBM's Peanut Begins New Computer Phase". The Boston Globe. Associated Press. November 1, 1983.

- "Penney Shelves its Computers". The Boston Globe. December 17, 1983.

- http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/issues/cgw_50.pdf#page=7 Archived April 18, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Mark Cerny. "The Long View". Game Developers Conference. Archived from the original on July 21, 2013.

- Seitz, Lee K., CVG Nexus: Timeline - 1980s, archived from the original (– Scholar search) on October 13, 2007, retrieved November 16, 2007

- Prince, Suzan (September 1983). "Faded Glory: The Decline, Fall and Possible Salvation of Home Video". Video Games. Pumpkin Press. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- Daglow, Don L. (August 1988). "The Changing Role of Computer Game Designers". Computer Gaming World. p. 18.

- Rosenberg, Ron (December 11, 1982). "Competitors Claim Role in Warner Setback". The Boston Globe. p. 1. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- Dvorak, John C (August 12, 1985). "Is the PCJr Doomed To Be Landfill?". InfoWorld. 7 (32): 64. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- Jary, Simon (August 19, 2011). "HP TouchPads to be dumped in landfill?". PC Advisor. Archived from the original on November 8, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- Kennedy, James (August 20, 2011). "Book Review: Super Mario". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- "NES". Icons. Season 4. Episode 5010. December 1, 2005. G4. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012.

- "25 Smartest Moments in Gaming". GameSpy. July 21–25, 2003. p. 22. Archived from the original on September 2, 2012.

- O'Kane, Sean (October 18, 2015). "7 things I learned from the designer of the NES". The Verge. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- Katz, Arnie (January 1985). "1984: The Year That Shook Electronic Gaming". Electronic Games. 3 (35): 30–31 [30]. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- Halfhill, Tom R. "A Turning Point for Atari? Report from the Winter Consumer Electronics Show". Archived from the original on April 9, 2016.

- Liedholm, Marcus and Mattias. "The Famicom rules the world! – (1983–89)". Nintendo Land. Archived from the original on January 1, 2010. Retrieved February 14, 2006.

- Dvorchak, Robert (July 30, 1989). "NEC out to dazzle Nintendo fans". The Times-News. p. 1D. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- "Gainesville Sun - Google News Archive Search".

- "Toy Trends", Orange Coast, Emmis Communications, 14 (12), p. 88, December 1988, ISSN 0279-0483, retrieved April 26, 2011

- Takiff, Jonathan (June 20, 1986). "Video Games Gain in Japan, Are Due For Assault on U.S." The Vindicator. p. 2. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- Lock, Robert; Halfhill, Tom R. (July 1986). "Editor's Notes". Compute!. p. 6. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- Leemon, Sheldon (February 1987). "Microfocus". Compute!. p. 24. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- "Ten Facts about the Great Video Game Crash of '83". Archived from the original on May 10, 2015.

Around the time home consoles started falling out of favor, home computers like the Commodore Vic-20, the Commodore 64, and the Apple ][ became affordable for the average family. Needless to say, the computer manufacturers of the age seized on the opportunity to ask parents, "Hey, why are you spending money on a game console when a computer can let you play games and prepare you for a job?"

- Naramura, Yuki (January 23, 2019). "Peak Video Game? Top Analyst Sees Industry Slumping in 2019". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- "Down Many Times, but Still Playing the Game: Creative Destruction and Industry Crashes in the Early Video Game Industry 1971-1986" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 1, 2014.

- Parish, Jermey (August 28, 2014). "Greatest Years in Gaming History: 1983". USGamer. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- Consalvo, Mia (2006). "Console video games and global corporations: Creating a hybrid culture". New Media & Society. 8 (1): 117–137. doi:10.1177/1461444806059921.

- Kinder, Marsha (1993), Playing with Power in Movies, television, and Video Games: From Muppet Babies to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, University of California Press, p. 90, ISBN 0-520-07776-8, retrieved April 26, 2011

- Plunkett, Luke (July 21, 2012). "Konami's Cheat to Get Around a Silly Nintendo Rule". Kotaku. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- Cunningham, Andrew (July 15, 2013). "The NES turns 30: How it began, worked, and saved an industry". Ars Technica. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- U.S. Court of Appeals; Federal Circuit (1992). "Atari Games Corp. v. Nintendo of America Inc". Digital Law Online. Archived from the original on August 8, 2011. Retrieved March 30, 2005.

Further reading

- DeMaria, Rusel & Wilson, Johnny L. (2003). High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill/Osborne. ISBN 0-07-222428-2.

- Gallagher, Scott & Park, Seung Ho (2002). "Innovation and Competition in Standard-Based Industries: A Historical Analysis of the U.S. Home Video Game Market". IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, vol. 49, no. 1, February 2002, pp. 67–82. doi: 10.1109/17.985749

External links

- The Dot Eaters.com: "Chronicle of the Great Videogame Crash"

- Twin Galaxies Official Video Game & Pinball Book of World Records: "The Golden Age of Video Game Arcades" — story within the 1998 book.

- Intellivisionlives.com: Official Intellivision History — by the original programmers.

- The History of Computer Games: The Atari Years — by Chris Crawford, a game designer at Atari during the crash.

- Pctimeline.info: Chronology of the Commodore 64 Computer — Events & Game release dates (1982–1990).