Video games in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom is Europe's second largest video game market after Germany and the fifth largest in the world.[1] The UK video game market was worth £5.7 billion in 2018, a 10% increase over the previous year.[2] From this, £4.01 billion was from the sales of software (+10.3% increase over 2017), £1.57 billion from the sales of hardware (+10.7% increase), and £0.11 billion from the sales of other game related items.[3] In the software market, the data showed a significant increase in digital and online revenues, up +20.3% to a record £2.01bn.[4] £1.17 billion of software sales came from mobile games. In 2017, the number of players was estimated at 32.4 million people.[5]

In 2009, the profits of Britain's video game industry exceeded those from its film industry for the first time.[6] Many major video game franchises are developed in the UK, including Grand Theft Auto, Tomb Raider, Burnout, LittleBigPlanet, Wipeout and Dirt, making UK the third largest producer of video game series behind Japan and United States. The best-selling video game series made in the UK is Grand Theft Auto (primary developed by Rockstar North in Edinburgh, Scotland) which the series has sold over 150 million copies as of September 2013, the recent instalment Grand Theft Auto V became the fastest-selling video game of all time by making $815.7 million (£511.8 million) in sales worldwide during the first 24 hours of the game's sale. Grand Theft Auto V went on to break several other records such as Best-selling action-adventure video game in 24 hours, Fastest entertainment property to gross $1 billion, Fastest video game to gross $1 billion, Highest grossing video game in 24 hours, Highest revenue generated by an entertainment product in 24 hours and Most viewed trailer for an action-adventure video game.[7]

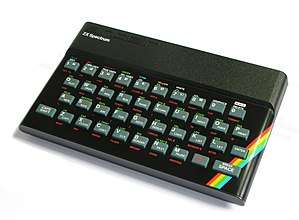

The organisations responsible for rating video games in the UK are the British Board of Film Classification and PEGI, the latter of which was elected to rate British games in 2009 and subsequently began doing so in July 2012.[8] The United Kingdom's video game industry is estimated to employ 20,000 people.[9] One of the United Kingdom's greatest contributions to the worldwide gaming industry was the 1982 release of the ZX Spectrum home computer.

The Video Games Tax Relief (VGTR) was established in 2014 to help support creativity in the UK games industry. According to TIGA,[10] prior to this, the UK Games industry was lagging behind other countries where game developers benefitted from substantial tax breaks and government grants: “Between 2008 and 2011, employment in the [games industry] fell by over 10 per cent and investment fell by £48 million”. Thus the UK VGTR aims to ensure the UK games industry’s competitiveness on the global stage, promotes investment and job creation and encourage the production of culturally British video games. The key benefit of the tax relief is that qualifying companies can claim up to 20% of their “core expenditure” back, provided that expenditure has been made in the European Economic Area.[11]

In recent years, Northern Ireland has made increasing contributions to the United Kingdom's video game industry.[12] In March 2012, Parliament instated certain tax reliefs for UK game developers.[13]

History

Early History (1950's)

Microcomputer popularity (1981–1984)

Whereas the North American and Japanese video game industry boomed with console games, the UK market for video games was grown out of home computers, specifically the BBC Micro by Acorn Computer in 1981, and the ZX Spectrum from Sinclair Research (alongside Sinclair's earlier ZX80 and ZX81 systems) and the Commodore 64 by Commodore International in 1982.[14][15] While some of the first generation of video game consoles like dedicated Pong consoles, had made their way to the UK, they did not gain much traction.[16] Additionally, there had been home computers available to the UK earlier than this, including the Commodore PET and Apple II (both released in 1977), but these were comparatively expensive.[17] Computer literacy had been seen as a key skill that Britian's children should possess to help improve the technology savvy of the nation in the future, and the BBC worked with Acorn to create the low-cost BBC Micro home computer alongside a set of broadcast programming to help teach fundamentals of computers for school-aged children. This was used in up to 80% of the schools in the UK at the time, and led to creation of the Spectrum and Commodore 64 to help meet growing demand for the systems.[18] Additionally, youth of the United Kingdom at that time were tinkerers, taking apart and repairing devices including electronics, and the nature of computer programming felt within this same scope.[19]

The United Kingdom had already had a history with board games prior to this revolution, as well as laying claim to starting the fantasy literary genre through J.R.R. Tolkien's works, a major point of inspiration for the Dungeons & Dragons tabletop role-playing game.[20] Thus, with the ability to program their own games through these early home computers, UK developed an initial home computer game market, with games typically made by only one person with no formal experience in computer programming, known as "bedroom coders".[16][21] As there were few game stores in the UK at that time, most of these coders turned to mail order, sending out copies of their games on cassette tape for use in the computer's tape drives. A market developed for companies to help such programmer sell and distribute their games.[17] This industry took off after the release of the ZX Spectrum in 1983: by the end of that year, there were more than 450 companies selling video games on cassette compared to 95 the year before.[17] An estimated 10,000 to 50,000 youth, mostly male, were making games out of their homes at this time based on advertisements for games in popular magazines.[19] The growth of video games in the UK during this period was comparable to the punk subculture, fueled by young people making money from their games.[19]

One of the earliest such successful titles was Manic Miner, developed and released by Matthew Smith in 1983, sold by Bug-Byte, one of the first publishers in this market. While a loose clone of the United States-developed Miner 2049er, Manic Miner incorporated elements of British humour and other oddities.[17][22] Manic Miner is considered the quintessential "British game" for this reason, and since then, inspired similar games with the same type of British wit and humour through the present.[20][22][23]

Because video game consoles did not take hold in the UK during these formulative years, the video game crash of 1983 which struck the North America market has little impact on the video game industry in the UK. However, the video game industry in the UK during this period still had notable failures. The company Imagine Software, formed by former members of Bug-Byte, had become successful prior to 1982, and drew the attention of the BBC as part of a documentary series Commercial Breaks that had been examining successful businesses in new industries. During 1983 and 1984, Imagine had tried to expand its capabilities beyond game programming as well as push the idea of "megagames" that stretched a computer's hardware limits and would be sold at a higher cost, but these efforts backfired, costing Imagine staff and money. By the time the BBC began filming for this episode of Commercial Breaks, Imagine was in a downward spiral, which was notoriously documented by the BBC.[24]

Advances with the Amiga (1985–1995)

This computer game revolution was subsequently boosted by the release of the Commodore Amiga in 1985.[25] The Amiga had more powerful graphics capabilities compared to previous home computers and enabled game developers to experiment more.[25] Besides video games, the Amiga also helped to expand the demoscene in the UK, which in turn brought in more developers to stretch the capabilities of the computer.[26]

Out of this period rose a number of influential British companies on the global video game industry today:

- Psygnosis was formed in 1984 after the closure of Imagine Software, and sought to bring the brightest programmers of the day to produce games that they would then publish, along with other in-house developed titles. Psygnosis' catalog has a number of highly-praised titles such as Shadow of the Beast and Obliterator. The publisher was eventually acquired by Sony Interactive Entertainment to develop the Wipeout series among other titles, and while the studio was shuttered in 2012, most of its activities had been adsorbed into the Sony structure.[25]

- DMA Design, which among their first titles was the best-selling Lemmings in 1991 and established the recognition of the firm. DMA Design, after several more titles, would go on to produce Grand Theft Auto in 1997, and would lead them to ultimately be acquired by Take Two Interactive and rebranded as Rockstar Games, with the original studio renamed as Rockstar North.[25]

- Bullfrog Productions was founded by Peter Molyneux and Les Edgar, with one of their first titles being Populous, the title that established the god game genre. Bullfrog developed several other influential titles, including the Dungeon Keeper series, the Syndicate series, and Theme-related titles including Theme Park and Theme Hospital. Though Bullfrog was ultimately acquired and shuttered by Electronic Arts, the Bullfrog team went on to establish other influential UK studios, including Molyneux's Lionhead Studios, Media Molecule, Hello Games, and Two Point Studios.[25]

- Team17 was initially born out of the demoscene, but produced a number of success Amiga games, finding success in the Worms series in 1995. Today, Team17 also now serves as a video game publishers for many independent studios.[25]

During this period, video game consoles from the fourth generation, such as the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, began to gain interest in the UK.[16] Such interest lead to more corporate structure around video game development to support the costs and hardware needed to develop games on these platforms, and caused a decline of the popularity of the bedroom coder by 1995.[16][19] However, the bedroom coders had seeded the necessary elements as to gain interest from United States companies looking for talent around this time, leading to various acquisitions and partnerships between US and UK game companies around this time.[16]

The combined era of 1980s microcomputer and early 90s Amiga game development in Britain is known as "Britsoft".[27]

Console systems (1995–2009)

The Amiga's legacy helped to transition video games from the 8-bit second generation to the 32-bit fifth generation, with systems like the Sony's PlayStation and Nintendo 64.[25] With these consoles having caught up to the power that the home computers had, UK developers began to target these platforms.[20]

Indie gaming (2010–2013)

While large British studios continued to develop high-profile games for consoles and computers, a new hobbyist interest arose around 2010 in independent game development. The indie game model of development started to become popular in the late 2000s, with games like World of Goo, Super Meat Boy, and Fez showing the success of the small indie team model and the means to distribute these via digital channels rather than retail. This in turn rekindled the hobbyist programmer mindset in the United Kingdom, starting a new wave of individual and small team British developers.[27]

Media

In 2000, Channel 4 produced a documentary, Thumb Candy, on the history of video games.[28] It includes footage from old Nintendo commercials.[29]

Video game conventions in the United Kingdom

Game ratings and government oversight

Prior to 2012, video games in the UK would be rated through the Video Standards Council (VSC), which had been established in 1989 under the government's Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). The VSC worked initially with the UK video game trade group known as the Entertainment Leisure Software Publishers Association (ELSPA) at the time but later renamed to the UK Interactive Entertainment Association (UKIE). The VSC and ELPSA developed a set of ratings in 1993, and used a combination of voluntary suggestions from publishers and their own reviews to establish a game's rating.[30] With the introduction of the Pan European Game Information (PEGI) system in 2003, the VSC standardized its ratings on PEGI's classification system. The VSC system was voluntary at this point, though most UK retailers would respect the ratings marked on boxes to avoid selling mature games to children.[30] The only facet of the UK ratings system for video games set in law were for titles deemed to have excessive violent or pornographic content; such titles were required to be reviewed by the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC), a non-government body designed in law to review film and television content, if such a designation was determined by the VSC. Legal penalties existed for publishers and retailers that attempted to sell such games without the BBFC's review. The BBFC had the authority to outright ban sale of a video game if deemed so, though such bans could be challenged.[30] Up to 2012, only two such games had been temporarily banned by the BBFC due to rating: Manhunt 2 and Carmageddon, both which were later cleared after changed had been made by their publishers.[31]

The Byron Review, released in March 2008 under a 2007 order from Prime Minister Gordon Brown to the Department for Children, Schools and Families, made numerous suggestions for how the government could take steps to protect children in the digital environment like the Internet.[31] Among the suggestions were related to video game ratings, which the report found that parents often mistook as difficulty ratings, and instead urged that the BBFC become involved. By May 2008, the BBFC had proposed a new voluntary ratings system for digital video games, paralleling their existing rating systems for film and television.[32] The VSC and other groups felt the BBFC's system for video games was too forgiving and was based on a system designed around linean content rather that non-linear content such as video games,[33][34] and urged the government to adopt a system based on an enhanced PEGI categorization system they were working on.[35] Reports had found that the PEGI system tended to rate games more conservatively - issuing the game a stricter age rating - compared to what the BBFC would issue for the same title; the VSC stated that 50% of the games they had rated "18+" on the PEGI since 2003 had received a more lenient rating from the BBFC.[36]

The DCMS issued a following report in June 2009 to address several points of the Byron Review, among which included the intent to standardized video game ratings on the PEGI system.[31] The Video Recordings (Labelling) Regulations act was passed in May 2012 and came into force on 30 July 2012.[37] With it, it eliminated the BBFC's oversight of video games with limited exceptions on excessively pornographic titles, as well as for games with limited interactivity (such as interactive DVD games) and for any direct video content on the game disc.[38] Instead, all published video games in retail marketplaces were required to be rated under the PEGI system by the special Games Ratings Authority (GRA) within the VSC. Retailers were bound to prevent sales of mature games (PEGI ratings of 12, 16, or 18) to younger children under this law, with both fines and prison time should they be found guilty of such sales.[39][31] The VSC also became the only body that could ban sale of a game in the UK.[38] UKIE continues to work alongside the VSC to help UK developers and publishers prepare for the VSC process and prepare educational and advocacy material to make the UK public aware of the ratings system.[38]

The VSC ratings only apply to retail titles; digitally distributed titles are not regulated under UK law, through the VSC urges developers, publishers, and storefronts as a best-practice to use the low-cost self-ratings services of the International Age Rating Coalition to assign their game an appropriate PEGI rating for the digital service.[40]

Legacy

The Royal Mail issued a limited postal stamp series in 2020 featuring several games that formed the basis of the United Kingdom's early video game industry. The series featured Elite (1984), the Dizzy series (1987–1992), WipeOut (1995), the Worms series (1995–present), Lemmings (1991), Micro Machines (1991), Populus (1989), and the Tomb Raider series (1996–present).[41]

References

- . NewZoo (2014-06-23). Retrieved on 2016-04-06.

- https://ukie.org.uk/news/2019/04/uk-consumer-spend-games-grows-10-record-%c2%a357bn-2018

- "UK gaming market worth record £5.7bn". BBC. 2019-04-02. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- Luke, Hebblethwaite (2019-04-02). "UK consumer spend on games grows 10% to a record £5.7bn in 2018". UK Interactive Entertainment Association. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- https://www.ign.com/articles/2019/04/19/top-10-best-selling-video-games-of-all-time

- Rosenberg, Dave. (2009-12-31) Video games outsell movies in U.K. | Software, Interrupted - CNET News. News.cnet.com. Retrieved on 2011-05-07.

- "Grand Theft Auto 5 breaks 6 sales world records". Guinness World Records.

- "PEGI ratings become UK's single video game age rating system". The Association For UK Interactive Entertainment. 2012-07-30. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- "Creative Industries Economic Estimates: Focus on..." Department for Culture, Media and Sport. 2016-06-09. Retrieved 2016-09-09.

- http://www.tiga.org/repository/documents/editorfiles/reports/june_2014___guide_to_video_games_tax_relief.pdf

- http://insights.pollen.vc/funding/why-havent-you-applied-for-the-uk-video-games-tax-relief

- "BBC News - The changing face of NI's video gaming industry". BBC. 2010-05-25. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- Henderson, Rik (2012-03-21). "UK tax relief break". Retrieved 2012-03-31.

- Stewart, Keith (24 February 2017). "10 most influential games consoles – in pictures". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- "Commodore 64 turns 30: What do today's kids make of it?". BBC News. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

- Izushi, Hiro; Aoyama, Yuko (2006). "Industry evolution and cross-sectoral skill transfers: a comparative analysis of the video game industry in Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom". Environment and Planning A. 38: 1843–1861. doi:10.1068/a37205.

- Baker, Chris (6 August 2010). "Sinclair ZX80 and the Dawn of 'Surreal' U.K. Game Industry". Wired. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Hormby, Thomas (8 February 2007). "Acorn and the BBC Micro: From education to obscurity". Low End Mac. Archived from the original on 3 March 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2007.

- Mardsen, Rhordi (25 January 2015). "Geeks Who Rocked The World: Documentary Looks Back At Origins Of The Computer-games Industry". The Independent. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- "How British video games became a billion pound industry". BBC. December 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- "Death of the bedroom coder". The Guardian. 24 January 2004. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Donlan, Christian (26 July 2012). "Manic Miner 360: Revisiting a Classic". Eurogamer. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Orr, Lucy (7 July 2011). "Bug-Byte Manic Miner". The Register. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Kean, Roger (December 1984). "The Biggest Commercial Break Of Them All". Crash. Newsfield Publications Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- Stuart, Keith (23 July 2015). "Commodore Amiga at 30 – the computer that made the UK games industry". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Reunanen, Markku; Silvast, Antti (2009). Demoscene Platforms: A Case Study on the Adoption of Home Computers. History of Nordic Computing. pp. 289–301. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-03757-3_30.

- Stuart, Keith (27 January 2010). "Back to the bedroom: how indie gaming is reviving the Britsoft spirit". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- Thumb Candy. Thumb Candy - The history of computer games 2000. YouTube. Published by QLvsJAGUAR. Published on 12 February 2011. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- Gaming Life UK. IGN. Published 24 June 2002. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- "Rated and Willing: Where Game Rating Boards Differ". Gamasutra. 15 December 2005. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "BBC News: UK enforces PEGI video game ratings system". BBC. 30 July 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "BBFC ratings go online". The Guardian. 21 May 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Hartley, Adam (23 June 2009). "Interview: ELSPA boss explains PEGI age ratings". TechRadar. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- Waters, Darren (8 July 2009). "Divide on games industry ratings". BBC. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- "Games ratings row gets colourful". BBC. 28 October 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Sassoon Coby, Alex (18 June 2009). "Spot On: British game-ratings changes broken down". GameSpot. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "Video Standards Council to take over games age ratings". BBC. 10 May 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Minkley, Johnny (26 June 2012). "VSC: "PEGI is stricter than the BBFC. We're not ashamed of that"". GamesIndustry.biz. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "MCV: PEGI ratings come into force today". MCVUK. 30 July 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Robertson, Andy (14 March 2019). "Digital Minister calls on all video game providers to use age ratings online - and parents agree". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Phillips, Tom (7 January 2020). "Royal Mail is putting Dizzy, Lemmings, and Elite on stamps". Eurogamer. Retrieved 7 January 2020.