History of personal computers

The history of the personal computer as a mass-market consumer electronic device began with the microcomputer revolution of the 1970s. A personal computer is one intended for interactive individual use, as opposed to a mainframe computer where the end user's requests are filtered through operating staff, or a time-sharing system in which one large processor is shared by many individuals. After the development of the microprocessor, individual personal computers were low enough in cost that they eventually became affordable consumer goods. Early personal computers – generally called microcomputers – were sold often in electronic kit form and in limited numbers, and were of interest mostly to hobbyists and technicians.

| History of computing |

|---|

| Hardware |

| Software |

| Computer science |

| Modern concepts |

| By country |

| Timeline of computing |

|

| Glossary of computer science |

|

Etymology

An early use of the term "personal computer" appeared in a 3 November 1962, New York Times article reporting John W. Mauchly's vision of future computing as detailed at a recent meeting of the Institute of Industrial Engineers. Mauchly stated, "There is no reason to suppose the average boy or girl cannot be master of a personal computer".[1]

In 1968, a manufacturer took the risk of referring to their product this way, when Hewlett-Packard advertised their "Powerful Computing Genie" as "The New Hewlett-Packard 9100A personal computer".[2] This advertisement was deemed too extreme for the target audience and replaced with a much drier ad for the HP 9100A programmable calculator.[3][4]

Over the next seven years, the phrase had gained enough recognition that Byte magazine referred to its readers in its first edition as "[in] the personal computing field",[5] and Creative Computing defined the personal computer as a "non-(time)shared system containing sufficient processing power and storage capabilities to satisfy the needs of an individual user."[6] In 1977, three new pre-assembled small computers hit the markets which Byte would refer to as the "1977 Trinity" of personal computing.[7] The Apple II and the PET 2001 were advertised as personal computers,[8][9] while the TRS-80 was described as a microcomputer used for household tasks including "personal financial management". By 1979, over half a million microcomputers were sold and the youth of the day had a new concept of the personal computer.[10]

Overview

The history of the personal computer as mass-market consumer electronic devices effectively began in 1977 with the introduction of microcomputers, although some mainframe and minicomputers had been applied as single-user systems much earlier. A personal computer is one intended for interactive individual use, as opposed to a mainframe computer where the end user's requests are filtered through operating staff, or a time sharing system in which one large processor is shared by many individuals. After the development of the microprocessor, individual personal computers were low enough in cost that they eventually became affordable consumer goods. Early personal computers – generally called microcomputers– were sold often in electronic kit form and in limited numbers, and were of interest mostly to hobbyists and technicians.

Mainframes, minicomputers, and microcomputers

Computer terminals were used for time sharing access to central computers. Before the introduction of the microprocessor in the early 1970s, computers were generally large, costly systems owned by large corporations, universities, government agencies, and similar-sized institutions. End users generally did not directly interact with the machine, but instead would prepare tasks for the computer on off-line equipment, such as card punches. A number of assignments for the computer would be gathered up and processed in batch mode. After the job had completed, users could collect the results. In some cases, it could take hours or days between submitting a job to the computing center and receiving the output.

A more interactive form of computer use developed commercially by the middle 1960s. In a time-sharing system, multiple computer terminals let many people share the use of one mainframe computer processor. This was common in business applications and in science and engineering.

A different model of computer use was foreshadowed by the way in which early, pre-commercial, experimental computers were used, where one user had exclusive use of a processor.[11] In places such as Carnegie Mellon University and MIT, students with access to some of the first computers experimented with applications that would today be typical of a personal computer; for example, computer aided drafting was foreshadowed by T-square, a program written in 1961, and an ancestor of today's computer games was found in Spacewar! in 1962. Some of the first computers that might be called "personal" were early minicomputers such as the LINC and PDP-8, and later on VAX and larger minicomputers from Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), Data General, Prime Computer, and others. By today's standards, they were very large (about the size of a refrigerator) and cost prohibitive (typically tens of thousands of US dollars). However, they were much smaller, less expensive, and generally simpler to operate than many of the mainframe computers of the time. Therefore, they were accessible for individual laboratories and research projects. Minicomputers largely freed these organizations from the batch processing and bureaucracy of a commercial or university computing center.

In addition, minicomputers were relatively interactive and soon had their own operating systems. The minicomputer Xerox Alto (1973) was a landmark step in the development of personal computers because of its graphical user interface, bit-mapped high resolution screen, large internal and external memory storage, mouse, and special software.[12]

In 1945, Vannevar Bush published an essay called "As We May Think" in which he outlined a possible solution to the growing problem of information storage and retrieval. In 1968, SRI researcher Douglas Engelbart gave what was later called The Mother of All Demos, in which he offered a preview of things that have become the staples of daily working life in the 21st century: e-mail, hypertext, word processing, video conferencing, and the mouse. The demo was the culmination of research in Engelbart's Augmentation Research Center laboratory, which concentrated on applying computer technology to facilitate creative human thought.

Microprocessor and cost reduction

The minicomputer ancestors of the modern personal computer used early integrated circuit (microchip) technology, which reduced size and cost, but they contained no microprocessor. This meant that they were still large and difficult to manufacture just like their mainframe predecessors. After the "computer-on-a-chip" was commercialized, the cost to manufacture a computer system dropped dramatically. The arithmetic, logic, and control functions that previously occupied several costly circuit boards were now available in one integrated circuit, making it possible to produce them in high volume. Concurrently, advances in the development of solid state memory eliminated the bulky, costly, and power-hungry magnetic core memory used in prior generations of computers.

The basic building block of every microprocessor and memory chip is the metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET, or MOS transistor),[13] which was originally invented by Mohamed Atalla and Dawon Kahng at Bell Labs in 1959.[14][15] The MOSFET made it possible to build high-density integrated circuits,[16][17] which led to the development of the first microprocessors.[18] The single-chip microprocessor was made possible by an improvement in MOS technology, the silicon-gate MOS chip, developed in 1968 by Federico Faggin, who later used silicon-gate MOS technology to develop the first single-chip microprocessor, the Intel 4004, in 1971.[18]

A few researchers at places such as SRI and Xerox PARC were working on computers that a single person could use and that could be connected by fast, versatile networks: not home computers, but personal ones.

After the 1972 introduction of the Intel 4004, microprocessor costs declined rapidly. In 1974 the American electronics magazine Radio-Electronics described the Mark-8 computer kit, based on the Intel 8008 processor. In January of the following year, Popular Electronics magazine published an article describing a kit based on the Intel 8080, a somewhat more powerful and easier to use processor. The Altair 8800 sold remarkably well even though initial memory size was limited to a few hundred bytes and there was no software available. However, the Altair kit was much less costly than an Intel development system of the time and so was purchased by companies interested in developing microprocessor control for their own products. Expansion memory boards and peripherals were soon listed by the original manufacturer, and later by plug compatible manufacturers. The very first Microsoft product was a 4 kilobyte paper tape BASIC interpreter, which allowed users to develop programs in a higher-level language. The alternative was to hand-assemble machine code that could be directly loaded into the microcomputer's memory using a front panel of toggle switches, pushbuttons and LED displays. While the hardware front panel emulated those used by early mainframe and minicomputers, after a very short time I/O through a terminal was the preferred human/machine interface, and front panels became extinct.

The beginnings of the personal computer industry

The “brain” [computer] may one day come down to our level [of the common people] and help with our income-tax and book-keeping calculations. But this is speculation and there is no sign of it so far.

IBM 610

The IBM 610 was designed between 1948 and 1957 by John Lentz at the Watson Lab at Columbia University as the Personal Automatic Computer (PAC) and announced by IBM as the 610 Auto-Point in 1957. Although it was faulted for its speed, the IBM 610 handled floating-point arithmetic naturally. With a price tag of $55,000, only 180 units were produced.[20]

Simon

Simon [21] was a project developed by Edmund Berkeley and presented in a thirteen articles series issued in Radio-Electronics magazine, from October 1950. Although there were far more advanced machines at the time of its construction, the Simon represented the first experience of building an automatic simple digital computer, for educational purposes. In fact, its ALU had only 2 bits, and the total memory was 12 bits (2bits x6). In 1950, it was sold for US$600.

Elea Olivetti

The Elea 9003 is one of a series of mainframe computers Olivetti developed starting in the late 1950s. The first prototype was created in 1957. The system, made entirely with transistors for high performance, was conceived, designed and developed by a small group of researchers led by Mario Tchou (1924–1961). It was the first solid-state computer designed (it was fully manufactured in Italy). The knowledge obtained was applied a few years later in the development of the successful Programma 101 electronic calculator.

LINC

Designed in 1962, the LINC was an early laboratory computer especially designed for interactive use with laboratory instruments. Some of the early LINC computers were assembled from kits of parts by the end users.[22]

Olivetti Programma 101

First produced in 1965, the Programma 101 was one of the first printing programmable calculators.[23][24][25][26][27] It was designed and produced by the Italian company Olivetti with Pier Giorgio Perotto being the lead developer. The Olivetti Programma 101 was presented at the 1965 New York World's Fair after 2 years work (1962- 1964). Over 44,000 units were sold worldwide; in the US its cost at launch was $3,200. It was targeted to offices and scientific entities for their daily work because of its high computing capabilities in small space and cost; also the NASA was amongst the first owners. Built without integrated circuits or microprocessors, it used only transistors, resistors and condensers for its processing,[28] the Programma 101 had features found in modern personal computers, such as memory, keyboard, printing unit, magnetic card reader/recorder, control and arithmetic unit.[29] HP later copied the Programma 101 architecture for its HP9100 series.[30][31]

MIR

The Soviet MIR series of computers was developed from 1965 to 1969 in a group headed by Victor Glushkov. It was designed as a relatively small-scale computer for use in engineering and scientific applications and contained a hardware implementation of a high-level programming language. Another innovative feature for that time was the user interface combining a keyboard with a monitor and light pen for correcting texts and drawing on screen.[32]

K-202

K-202 was a Polish PC computer designed between 1969 and 1970 and made its debut in 1971 in Poznań at the Poznań International Fair. The MSRP was $5000 which was an extremely competitive price. At the time of its introduction K-202 was the fastest PC computer in the world capable of performing one million operations per second. K-202 was designed by Polish computer engineer Jacek Karpiński and featured multiprogramming, multiprocessing, 16bit word architecture, and was based on TTL/MSI integrated circuits. Only 30 units of K-202 were ever produced and the company was shut down by a decree of communist regime.[33]

Datapoint 2200

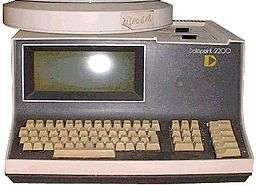

Released in June 1970, the programmable terminal called the Datapoint 2200 is among the earliest known devices that bears significant resemblance to the modern personal computer, with a CRT screen, keyboard, programmability, and program storage.[34] It was made by CTC (now known as Datapoint) and was a complete system in a case with the approximate footprint of an IBM Selectric typewriter.

The system's CPU was constructed from roughly a hundred (mostly) TTL logic components, which are groups of gates, latches, counters, etc. The company had commissioned Intel, and also Texas Instruments, to develop a single-chip CPU with that same functionality. TI designed a chip rather quickly, based on Intel's early drawings. But their attempt had several bugs and so did not work very well. Intel's version was delayed and both were a little too slow for CTC's needs. A deal was made that in return for not charging CTC for the development work, Intel could instead sell the processor as their own product, along with the supporting ICs they had developed. The first customer was Seiko, which approached Intel early on with this idea, based on what they had seen Busicom do with the 4004.

This became the Intel 8008. Although it demanded several additional ICs, it is generally known as the first 8-bit microprocessor.[35] The requirements of the Datapoint 2200 determined the 8008 architecture, which was later expanded into the 8080 and the Z80 upon which CP/M was designed. These CPUs in turn influenced the 8086, which defined the whole line of "x86" processors used in all IBM-compatible PCs to this day (2020).

Although the design of the Datapoint 2200's TTL based bit serial CPU and the Intel 8008 were technically very different, they were largely software-compatible. From a software perspective, the Datapoint 2200 therefore functioned as if it were using an 8008.

Kenbak-1

The Kenbak-1, released in early 1971, is considered by the Computer History Museum to be the world's first personal computer. It was designed and invented by John Blankenbaker of Kenbak Corporation in 1970, and was first sold in early 1971. Unlike a modern personal computer, the Kenbak-1 was built of small-scale integrated circuits, and did not use a microprocessor. The system first sold for US$750. Only around 40 machines were ever built and sold. In 1973, production of the Kenbak-1 stopped as Kenbak Corporation folded.

With only 256 bytes of memory, an 8-bit word size, and input and output restricted to lights and switches, and no apparent way to extend its power, the Kenbak-1 was most useful for learning the principles of programming but not capable of running application programs. Interestingly, 256 bytes of memory, 8 bit word size, and I/O limited to switches and lights on the front panel, are also the characteristics of the 1975 Altair 8800, whose faith was diametrically opposed to that of the Kenbak. The differentiating factor might have been the extensibility of the Altair, without which it was practically useless.

Micral N

The French company R2E was formed by two former engineers of the Intertechnique company to sell their Intel 8008-based microcomputer design. The system was developed at the Institut national de la recherche agronomique to automate hygrometric measurements. The system ran at 500 kHz and included 16 kB of memory, and sold for 8500 Francs, about $1300US.

A bus, called Pluribus, was introduced that allowed connection of up to 14 boards. Boards for digital I/O, analog I/O, memory, floppy disk were available from R2E. The Micral operating system was initially called Sysmic, and was later renamed Prologue.

R2E was absorbed by Groupe Bull in 1978. Although Groupe Bull continued the production of Micral computers, it was not interested in the personal computer market, and Micral computers were mostly confined to highway toll gates (where they remained in service until 1992) and similar niche markets.

Xerox Alto and Star

The Xerox Alto, developed at Xerox PARC in 1973, was the first computer to use a mouse, the desktop metaphor, and a graphical user interface (GUI), concepts first introduced by Douglas Engelbart while at International. It was the first example of what would today be recognized as a complete personal computer.[36][37] The first machines were introduced on 1 March 1973.[38]

In 1981, Xerox Corporation introduced the Xerox Star workstation, officially known as the "8010 Star Information System". Drawing upon its predecessor, the Xerox Alto, it was the first commercial system to incorporate various technologies that today have become commonplace in personal computers, including a bit-mapped display, a windows-based graphical user interface, icons, folders, mouse, Ethernet networking, file servers, print servers and e-mail.

While its use was limited to the engineers at Xerox PARC, the Alto had features years ahead of its time. Both the Xerox Alto and the Xerox Star would inspire the Apple Lisa and the Apple Macintosh.

IBM SCAMP

In 1972-1973 a team led by Dr. Paul Friedl at the IBM Los Gatos Scientific Center developed a portable computer prototype called SCAMP (Special Computer APL Machine Portable) based on the IBM PALM processor with a Philips compact cassette drive, small CRT and full function keyboard. SCAMP emulated an IBM 1130 minicomputer in order to run APL\1130.[39] In 1973 APL was generally available only on mainframe computers, and most desktop sized microcomputers such as the Wang 2200 or HP 9800 offered only BASIC. Because it was the first to emulate APL\1130 performance on a portable, single-user computer, PC Magazine in 1983 designated SCAMP a "revolutionary concept" and "the world's first personal computer".[39][40] The prototype is in the Smithsonian Institution.

IBM 5100

IBM 5100 was a desktop computer introduced in September 1975, six years before the IBM PC. It was the evolution of SCAMP (Special Computer APL Machine Portable) that IBM demonstrated in 1973. In January 1978 IBM announced the IBM 5110, its larger cousin. The 5100 was withdrawn in March 1982.

When the PC was introduced in 1981, it was originally designated as the IBM 5150, putting it in the "5100" series, though its architecture wasn't directly descended from the IBM 5100.

Altair 8800

Development of the single-chip microprocessor was the gateway to the popularization of cheap, easy to use, and truly personal computers. It was only a matter of time before one such design was able to hit a sweet spot in terms of pricing and performance, and that machine is generally considered to be the Altair 8800, from MITS, a small company that produced electronics kits for hobbyists.

The Altair was introduced in a Popular Electronics magazine article in the January 1975 issue. In keeping with MITS's earlier projects, the Altair was sold in kit form, although a relatively complex one consisting of four circuit boards and many parts. Priced at only $400, the Altair tapped into pent-up demand and surprised its creators when it generated thousands of orders in the first month. Unable to keep up with demand, MITS sold the design after about 10,000 kits had shipped.

The introduction of the Altair spawned an entire industry based on the basic layout and internal design. New companies like Cromemco started up to supply add-on kits, while Microsoft was founded to supply a BASIC interpreter for the systems. Soon after a number of complete "clone" designs, typified by the IMSAI 8080, appeared on the market. This led to a wide variety of systems based on the S-100 bus introduced with the Altair, machines of generally improved performance, quality and ease-of-use.

The Altair, and early clones, were relatively difficult to use. The machines contained no operating system in ROM, so starting it up required a machine language program to be entered by hand via front-panel switches, one location at a time. The program was typically a small driver for an attached cassette tape reader, which would then be used to read in another "real" program. Later systems added bootstrapping code to improve this process, and the machines became almost universally associated with the CP/M operating system, loaded from floppy disk.

The Altair created a new industry of microcomputers and computer kits, with many others following, such as a wave of small business computers in the late 1970s based on the Intel 8080, Zilog Z80 and Intel 8085 microprocessor chips. Most ran the CP/M-80 operating system developed by Gary Kildall at Digital Research. CP/M-80 was the first popular microcomputer operating system to be used by many different hardware vendors, and many software packages were written for it, such as WordStar and dBase II.

Homebrew Computer Club

Although the Altair spawned an entire business, another side effect it had was to demonstrate that the microprocessor had so reduced the cost and complexity of building a microcomputer that anyone with an interest could build their own. Many such hobbyists met and traded notes at the meetings of the Homebrew Computer Club (HCC) in Silicon Valley. Although the HCC was relatively short-lived, its influence on the development of the modern PC was enormous.

Members of the group complained that microcomputers would never become commonplace if they still had to be built up, from parts like the original Altair, or even in terms of assembling the various add-ons that turned the machine into a useful system. What they felt was needed was an all-in-one system. Out of this desire came the Sol-20 computer, which placed an entire S-100 system – QWERTY keyboard, CPU, display card, memory and ports – into an attractive single box. The systems were packaged with a cassette tape interface for storage and a 12" monochrome monitor. Complete with a copy of BASIC, the system sold for US$2,100. About 10,000 Sol-20 systems were sold.

Although the Sol-20 was the first all-in-one system that we would recognize today, the basic concept was already rippling through other members of the group, and interested external companies.

Other machines of the era

Other 1977 machines that were important within the hobbyist community at the time included the Exidy Sorcerer, the NorthStar Horizon, the Cromemco Z-2, and the Heathkit H8.

1977 and the emergence of the "Trinity"

By 1976, there were several firms racing to introduce the first truly successful commercial personal computers. Three machines, the Apple II, PET 2001 and TRS-80 were all released in 1977,[41] becoming the most popular by late 1978.[42] Byte magazine later referred to them as the "1977 Trinity".[43] Also in 1977, Sord Computer Corporation released the Sord M200 Smart Home Computer in Japan.[44]

Apple II

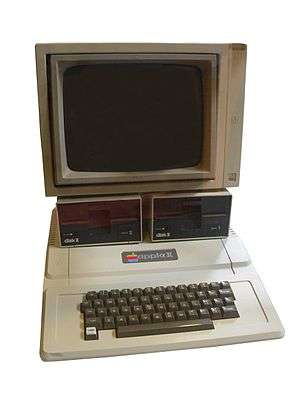

Steve Wozniak (known as "Woz"), a regular visitor to Homebrew Computer Club meetings, designed the single-board Apple I computer and first demonstrated it there. With specifications in hand and an order for 100 machines at US$500 each from the Byte Shop, Woz and his friend Steve Jobs founded Apple Computer.

About 200 of the machines sold before the company announced the Apple II as a complete computer. It had color graphics, a full QWERTY keyboard, and internal slots for expansion, which were mounted in a high quality streamlined plastic case. The monitor and I/O devices were sold separately. The original Apple II operating system was only the built-in BASIC interpreter contained in ROM. Apple DOS was added to support the diskette drive; the last version was "Apple DOS 3.3".

Its higher price and lack of floating point BASIC, along with a lack of retail distribution sites, caused it to lag in sales behind the other Trinity machines until 1979, when it surpassed the PET. It was again pushed into 4th place when Atari introduced its popular Atari 8-bit systems.[45]

Despite slow initial sales, the Apple II's lifetime was about eight years longer than other machines, and so accumulated the highest total sales. By 1985 2.1 million had sold and more than 4 million Apple II's were shipped by the end of its production in 1993.[46]

PET

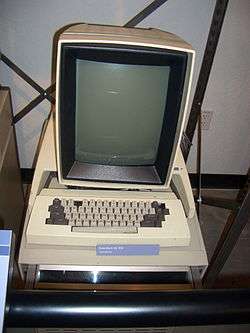

Chuck Peddle designed the Commodore PET (short for Personal Electronic Transactor) around his MOS 6502 processor. It was essentially a single-board computer with a simple TTL-based CRT driver circuit driving a small built-in monochrome monitor with 40×25 character graphics. The processor card, keyboard, monitor and cassette drive were all mounted in a single metal case. In 1982, Byte referred to the PET design as "the world's first personal computer".[47]

The PET shipped in two models; the 2001–4 with 4 kB of RAM, or the 2001–8 with 8 kB. The machine also included a built-in Datassette for data storage located on the front of the case, which left little room for the keyboard. The 2001 was announced in June 1977 and the first 100 units were shipped in mid October 1977.[48] However they remained back-ordered for months, and to ease deliveries they eventually canceled the 4 kB version early the next year.

Although the machine was fairly successful, there were frequent complaints about the tiny calculator-like keyboard, often referred to as a "Chiclet keyboard" due to the keys' resemblance to the popular gum candy. This was addressed in the upgraded "dash N" and "dash B" versions of the 2001, which put the cassette outside the case, and included a much larger keyboard with a full stroke non-click motion. Internally a newer and simpler motherboard was used, along with an upgrade in memory to 8, 16, or 32 KB, known as the 2001-N-8, 2001-N-16 or 2001-N-32, respectively.

The PET was the least successful of the 1977 Trinity machines, with under 1 million sales.[46]

TRS-80

Tandy Corporation (Radio Shack) introduced the TRS-80, retroactively known as the Model I as improved models were introduced. The Model I combined the motherboard and keyboard into one unit with a separate monitor and power supply. Although the PET and the Apple II offered certain features that were greatly advanced in comparison, Tandy's 3000+ Radio Shack storefronts ensured that it would have widespread distribution that neither Apple nor Commodore could touch.

The Model I used a Zilog Z80 processor clocked at 1.77 MHz (the later models were shipped with a Z80A processor). The basic model originally shipped with 4 kB of RAM, and later 16 kB, in the main computer. The expansion unit allowed for RAM expansion for a total of 48K. Its other strong features were its full stroke QWERTY keyboard, small size, well written Microsoft floating-point BASIC and inclusion of a monitor and tape deck for approximately half the cost of the Apple II. Eventually, 5.25 inch floppy drives were made available by Tandy and several third party manufacturers. The expansion unit allowed up to four floppy drives to be connected, provided a slot for the RS-232 option and a parallel port for printers.

The Model I could not meet FCC regulations on radio interference due to its plastic case and exterior cables. Apple resolved the issue with an interior metallic foil but the solution would not work for Tandy with the Model I.[49] Since the Model II and Model III were already in production Tandy decided to stop manufacturing the Model I. Radio Shack had sold 1.5 million Model I's by the cancellation in 1981.[46]

Home computers

Byte in January 1980 announced in an editorial that "the era of off-the-shelf personal computers has arrived". The magazine stated that "a desirable contemporary personal computer has 64 K of memory, about 500 K bytes of mass storage on line, any old competently designed computer architecture, upper and lowercase video terminal, printer, and high-level languages". The author reported that when he needed to purchase such a computer quickly he did so at a local store for $6000 in cash, and cited it as an example of "what the state of the art is at present ... as a mass-produced product".[50] By early that year Radio Shack, Commodore, and Apple manufactured the vast majority of the one half-million microcomputers that existed.[51] As component prices continued to fall, many companies entered the computer business. This led to an explosion of low-cost machines known as home computers that sold millions of units before the market imploded in a price war in the early 1980s.

Atari 400/800

Atari, Inc. was a well-known brand in the late 1970s, both due to their hit arcade games like Pong, as well as the hugely successful Atari VCS game console. Realizing that the VCS would have a limited lifetime in the market before a technically advanced competitor came along, Atari decided they would be that competitor, and started work on a new console design that was much more advanced.

While these designs were being developed, the Trinity machines hit the market with considerable fanfare. Atari's management decided to change their work to a home computer system instead. Their knowledge of the home market through the VCS resulted in machines that were almost indestructible and just as easy to use as a games machine—simply plug in a cartridge and go. The new machines were first introduced as the Atari 400 and 800 in 1978, but production problems prevented widespread sales until the next year.

With a trio of custom graphics and sound co-processors and a 6502 CPU clocked ~80% faster then most competitors, the Atari machines had capabilities that no other microcomputer could match. In spite of a promising start with about 600,000 sold by 1981, they were unable to compete effectively with Commodore's introduction of the Commodore 64 in 1982, and only about 2 million machines were produced by the end of their production run.[46] The 400 and 800 were tweaked into superficially improved models—the 1200XL, 600XL, 800XL, 65XE—as well as the 130XE with 128K of bank-switched RAM.

Sinclair

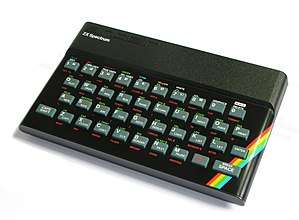

Sinclair Research Ltd is a British consumer electronics company founded by Sir Clive Sinclair in Cambridge. It was incorporated in 1973 as Ablesdeal Ltd. and renamed "Westminster Mail Order Ltd" and then "Sinclair Instrument Ltd." in 1975. The company remained dormant until 1976, when it was activated with the intention of continuing Sinclair's commercial work from his earlier company Sinclair Radionics; it adopted the name Sinclair Research in 1981. In 1980, Clive Sinclair entered the home computer market with the ZX80 at £99.95, at the time the cheapest personal computer for sale in the UK. In 1982 the ZX Spectrum was released, later becoming Britain's best selling computer, competing aggressively against Commodore and British Amstrad. At the height of its success, and largely inspired by the Japanese Fifth Generation Computer programme, the company established the "MetaLab" research centre at Milton Hall (near Cambridge), in order to pursue artificial intelligence, wafer-scale integration, formal verification and other advanced projects. The combination of the failures of the Sinclair QL computer and the TV80 led to financial difficulties in 1985, and a year later Sinclair sold the rights to their computer products and brand name to Amstrad. Sinclair Research Ltd exists today as a one-man company, continuing to market Sir Clive Sinclair's newest inventions.

- ZX80

The ZX80 home computer was launched in February 1980 at £79.95 in kit form and £99.95 ready-built. In November of the same year Science of Cambridge was renamed Sinclair Computers Ltd.

- ZX81

The ZX81 (known as the TS 1000 in the United States) was priced at £49.95 in kit form and £69.95 ready-built, by mail order.

- ZX Spectrum

The ZX Spectrum was launched on 23 April 1982, priced at £125 for the 16 KB RAM version and £175 for the 48 KB version.

- Sinclair QL

The Sinclair QL was announced in January 1984, priced at £399. Marketed as a more sophisticated 32-bit microcomputer for professional users, it used a Motorola 68008 processor. Production was delayed by several months, due to unfinished development of hardware and software at the time of the QL's launch.

- ZX Spectrum+

The ZX Spectrum+ was a repackaged ZX Spectrum 48K launched in October 1984.

- ZX Spectrum 128

The ZX Spectrum 128, with RAM expanded to 128 kB, a sound chip and other enhancements, was launched in Spain in September 1985 and the UK in January 1986, priced at £179.95.

TI-99

Texas Instruments (TI), at the time the world's largest chip manufacturer, decided to enter the home computer market with the Texas Instruments TI-99/4A. Announced long before its arrival, most industry observers expected the machine to wipe out all competition – on paper its performance was untouchable, and TI had enormous cash reserves and development capability.

When it was released in late 1979, TI took a somewhat slow approach to introducing it, initially focusing on schools. Contrary to earlier predictions, the TI-99's limitations meant it was not the giant-killer everyone expected, and a number of its design features were highly controversial. A total of 2.8 million units were shipped before the TI-99/4A was discontinued in March 1984.

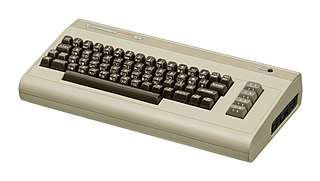

VIC-20 and Commodore 64

Realizing that the PET could not easily compete with color machines like the Apple II and Atari, Commodore introduced the VIC-20 in 1980 to address the home market. The tiny 5 kB memory and its relatively limited display in comparison to those machines was offset by a low and ever falling price. Millions of VIC-20s were sold.

The best-selling personal computer of all time was released by Commodore International in 1982. The Commodore 64 sold over 17 million units before its end.[46][52] The C64 name derived from its 64kb of RAM. It used the 6510 microprocessor, a variant of the 6502. MOS Technology, Inc. was then owned by Commodore.

BBC Micro

The BBC became interested in running a computer literacy series, and sent out a tender for a standardized small computer to be used with the show. After examining several entrants, they selected what was then known as the Acorn Proton and made a number of minor changes to produce the BBC Micro. The Micro was relatively expensive, which limited its commercial appeal, but with widespread marketing, BBC support and wide variety of programs, the system eventually sold as many as 1.5 million units. Acorn was rescued from obscurity, and went on to develop the ARM processor (Acorn RISC Machine) to power follow-on designs. The ARM is widely used to this day, powering a wide variety of products like the iPhone. ARM processors also run the worlds fastest supercomputer, record set in June 2020 Fugaku ARM Super computer. The Micro is not to be confused with the BBC Micro Bit, another BBC microcomputer released in March 2016.

Commodore/Atari price war and crash

The current personal computer market is about the same size as the total potato-chip market. Next year it will be about half the size of the pet-food market, and is fast approaching the total worldwide sales of panty hose.

— James Finke, President, Commodore International, February 1982[53]

In 1982, the TI 99/4A and Atari 400 were both $349, Radio Shack's Color Computer sold at $379, and Commodore had reduced the price of the VIC-20 to $199 and the Commodore 64 to $499.[54][55] TI had forced Commodore from the calculator market by dropping the price of its own-brand calculators to less than the cost of the chipsets it sold to third parties to make the same design. Commodore's CEO, Jack Tramiel, vowed that this would not happen again, and purchased MOS Technology to ensure a supply of chips. With his supply guaranteed, and good control over the component pricing, Tramiel launched a war against TI soon after the introduction of the Commodore 64.

Now vertically integrated,[56] Commodore lowered the retail price of the 64 to $300 at the June 1983 Consumer Electronics Show, and stores sold it for as little as $199. At one point the company was selling as many computers as the rest of the industry combined.[57] Commodore—which even discontinued list prices—could make a profit when selling the 64 for a retail price of $200 because of vertical integration.[58] Competitors also reduced prices; the Atari 800's price in July was $165,[59] and by the time TI was ready in 1983 to introduce the 99/2 computer—designed to sell for $99—the TI-99/4A sold for $99 in June. The 99/4A had sold for $400 in the fall of 1982, causing a loss for TI of hundreds of millions of dollars. A Service Merchandise executive stated "I've been in retailing 30 years and I have never seen any category of goods get on a self-destruct pattern like this". Such low prices probably hurt home computers' reputation; one retail executive said of the 99/4A, '"When they went to $99, people started asking 'What's wrong with it?'"[60][56] The founder of Compute! stated in 1986 that "our market dropped from 300 percent growth per year to 20 percent".[61]

While Tramiel's target was TI, everyone in the home computer market was hurt by the process; many companies went bankrupt or exited the business. In the end even Commodore's own finances were crippled by the demands of financing the massive building expansion needed to deliver the machines, and Tramiel was forced from the company.

Japanese computers

From the late 1970s to the early 1990s, Japan's personal computer market was largely dominated by domestic computer products. NEC's PC-88 and PC-98 was the market leader, though with some competition from the Sharp X1 and X68000, the FM-7 and FM Towns, and the MSX and MSX2, the latter also gaining some popularity in Europe. A key difference between Western and Japanese systems at the time was the latter's higher display resolutions (640x400) in order to accommodate Japanese text. Japanese computers also employed Yamaha FM synthesis sound boards since the early 1980s which produce higher quality sound. Japanese computers were widely used to produce video games, though only a small portion of Japanese PC games were released outside of the country.[62] The most successful Japanese personal computer was NEC's PC-98, which sold more than 18 million units by 1999.[63]

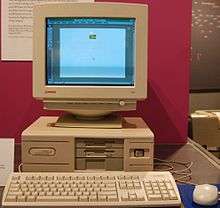

The IBM PC

IBM responded to the success of the Apple II with the IBM PC, released in August 1981. Like the Apple II and S-100 systems, it was based on an open, card-based architecture, which allowed third parties to develop for it. It used the Intel 8088 CPU running at 4.77 MHz, containing 29,000 transistors. The first model used an audio cassette for external storage, though there was an expensive floppy disk option. The cassette option was never popular and was removed in the PC XT of 1983.[64] The XT added a 10MB hard drive in place of one of the two floppy disks and increased the number of expansion slots from 5 to 8. While the original PC design could accommodate only up to 64k on the main board, the architecture was able to accommodate up to 640KB of RAM, with the rest on cards. Later revisions of the design increased the limit to 256K on the main board.

The IBM PC typically came with PC DOS, an operating system based upon Gary Kildall's CP/M-80 operating system. In 1980, IBM approached Digital Research, Kildall's company, for a version of CP/M for its upcoming IBM PC. Kildall's wife and business partner, Dorothy McEwen, met with the IBM representatives who were unable to negotiate a standard non-disclosure agreement with her. IBM turned to Bill Gates, who was already providing the ROM BASIC interpreter for the PC. Gates offered to provide 86-DOS, developed by Tim Paterson of Seattle Computer Products. IBM rebranded it as PC DOS, while Microsoft sold variations and upgrades as MS-DOS.

The impact of the Apple II and the IBM PC was fully demonstrated when Time named the home computer the "Machine of the Year", or Person of the Year for 1982 (3 January 1983, "The Computer Moves In"). It was the first time in the history of the magazine that an inanimate object was given this award.

IBM PC clones

The original PC design was followed up in 1983 by the IBM PC XT, which was an incrementally improved design; it omitted support for the cassette, had more card slots, and was available with a 10MB hard drive. Although mandatory at first, the hard drive was later made an option and a two floppy disk XT was sold. While the architectural memory limit of 640K was the same, later versions were more readily expandable.

Although the PC and XT included a version of the BASIC language in read-only memory, most were purchased with disk drives and run with an operating system; three operating systems were initially announced with the PC. One was CP/M-86 from Digital Research, the second was PC DOS from IBM, and the third was the UCSD p-System (from the University of California at San Diego). PC DOS was the IBM branded version of an operating system from Microsoft, previously best known for supplying BASIC language systems to computer hardware companies. When sold by Microsoft, PC DOS was called MS-DOS. The UCSD p-System OS was built around the Pascal programming language and was not marketed to the same niche as IBM's customers. Neither the p-System nor CP/M-86 was a commercial success.

Because MS-DOS was available as a separate product, some companies attempted to make computers available which could run MS-DOS and programs. These early machines, including the ACT Apricot, the DEC Rainbow 100, the Hewlett-Packard HP-150, the Seequa Chameleon and many others were not especially successful, as they required a customized version of MS-DOS, and could not run programs designed specifically for IBM's hardware. (See List of early non-IBM-PC-compatible PCs.) The first truly IBM PC compatible machines came from Compaq, although others soon followed.

Because the IBM PC was based on relatively standard integrated circuits, and the basic card-slot design was not patented, the key portion of that hardware was actually the BIOS software embedded in read-only memory. This critical element got reverse engineered, and that opened the floodgates to the market for IBM PC imitators, which were dubbed "PC clones". At the time that IBM had decided to enter the personal computer market in response to Apple's early success, IBM was the giant of the computer industry and was expected to crush Apple's market share. But because of these shortcuts that IBM took to enter the market quickly, they ended up releasing a product that was easily copied by other manufacturers using off the shelf, non-proprietary parts. So in the long run, IBM's biggest role in the evolution of the personal computer was to establish the de facto standard for hardware architecture amongst a wide range of manufacturers. IBM's pricing was undercut to the point where IBM was no longer the significant force in development, leaving only the PC standard they had established. Emerging as the dominant force from this battle amongst hardware manufacturers who were vying for market share was the software company Microsoft that provided the operating system and utilities to all PCs across the board, whether authentic IBM machines or the PC clones.

In 1984, IBM introduced the IBM Personal Computer/AT (more often called the PC/AT or AT) built around the Intel 80286 microprocessor. This chip was much faster, and could address up to 16MB of RAM but only in a mode that largely broke compatibility with the earlier 8086 and 8088. In particular, the MS-DOS operating system was not able to take advantage of this capability.

The bus in the PC/AT was given the name Industry Standard Architecture (ISA). Peripheral Component Interconnect (PCI) was released in 1992, and was supposed to replace ISA.

VESA Local Bus (VLB) and Extended ISA were also displaced by PCI, but a majority of later (post-1992) 486-based systems were featuring a VESA Local Bus video card. VLB importantly offered a less costly high speed interface for consumer systems, as only by 1994 was PCI commonly available outside of the server market.

PCI is later replaced by PCI-E (see below).

Apple Lisa and Macintosh

In 1983 Apple Computer introduced the first mass-marketed microcomputer with a graphical user interface, the Lisa. The Lisa ran on a Motorola 68000 microprocessor and came equipped with 1 megabyte of RAM, a 12-inch (300 mm) black-and-white monitor, dual 5¼-inch floppy disk drives and a 5 megabyte Profile hard drive. The Lisa's slow operating speed and high price (US$10,000), however, led to its commercial failure.

Drawing upon its experience with the Lisa, Apple launched the Macintosh in 1984, with an advertisement during the Super Bowl. The Macintosh was the first successful mass-market mouse-driven computer with a graphical user interface or 'WIMP' (Windows, Icons, Menus, and Pointers). Based on the Motorola 68000 microprocessor, the Macintosh included many of the Lisa's features at a price of US$2,495. The Macintosh was introduced with 128 kb of RAM and later that year a 512 kb RAM model became available. To reduce costs compared the Lisa, the year-younger Macintosh had a simplified motherboard design, no internal hard drive, and a single 3.5" floppy drive. Applications that came with the Macintosh included MacPaint, a bit-mapped graphics program, and MacWrite, which demonstrated WYSIWYG word processing.

While not a success upon its release, the Macintosh was a successful personal computer for years to come. This is particularly due to the introduction of desktop publishing in 1985 through Apple's partnership with Adobe. This partnership introduced the LaserWriter printer and Aldus PageMaker (now Adobe PageMaker) to users of the personal computer. During Steve Jobs' hiatus from Apple, a number of different models of Macintosh, including the Macintosh Plus and Macintosh II, were released to a great degree of success. The entire Macintosh line of computers was IBM's major competition up until the early 1990s.

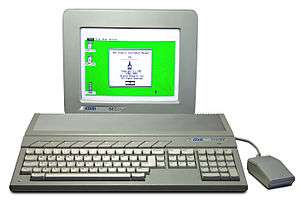

GUIs spread

In the Commodore world, GEOS was available on the Commodore 64 and Commodore 128. Later, a version was available for PCs running DOS. It could be used with a mouse or a joystick as a pointing device, and came with a suite of GUI applications. Commodore's later product line, the Amiga platform, ran a GUI operating system by default. The Amiga laid the blueprint for future development of personal computers with its groundbreaking graphics and sound capabilities. Byte called it "the first multimedia computer... so far ahead of its time that almost nobody could fully articulate what it was all about."[65]

In 1985, the Atari ST, also based on the Motorola 68000 microprocessor, was introduced with the first color GUI: Digital Research's GEM.

In 1987, Acorn launched the Archimedes range of high-performance home computers in Europe and Australasia. Based on their own 32-bit ARM RISC processor, the systems were shipped with a GUI OS called Arthur. In 1989, Arthur was superseded by a multi-tasking GUI-based operating system called RISC OS. By default, the mice used on these computers had three buttons.

PC clones dominate

The transition from a PC-compatible market being driven by IBM to one driven primarily by a broader market began to become clear in 1986 and 1987; in 1986, the 32-bit Intel 80386 microprocessor was released, and the first '386-based PC-compatible was the Compaq Deskpro 386. IBM's response came nearly a year later with the initial release of the IBM Personal System/2 series of computers, which had a closed architecture and were a significant departure from the emerging "standard PC". These models were largely unsuccessful, and the PC Clone style machines outpaced sales of all other machines through the rest of this period.[66] Toward the end of the 1980s PC XT clones began to take over the home computer market segment from the specialty manufacturers such as Commodore International and Atari that had previously dominated. These systems typically sold for just under the "magic" $1000 price point (typically $999) and were sold via mail order rather than a traditional dealer network. This price was achieved by using the older 8/16 bit technology, such as the 8088 CPU, instead of the 32-bits of the latest Intel CPUs. These CPUs were usually made by a third party such as Cyrix or AMD. Dell started out as one of these manufacturers, under its original name PC Limited.

1990s and 2000s

NeXT

In 1990, the NeXTstation workstation computer went on sale, for "interpersonal" computing as Steve Jobs described it. The NeXTstation was meant to be a new computer for the 1990s, and was a cheaper version of the previous NeXT Computer. Despite its pioneering use of Object-oriented programming concepts, the NeXTstation was somewhat a commercial failure, and NeXT shut down hardware operations in 1993.

CD-ROM

In the early 1990s, the CD-ROM became an industry standard, and by the mid-1990s one was built into almost all desktop computers, and towards the end of the 1990s, in laptops as well. Although introduced in 1982, the CD ROM was mostly used for audio during the 1980s, and then for computer data such as operating systems and applications into the 1990s. Another popular use of CD ROMs in the 1990s was multimedia, as many desktop computers started to come with built-in stereo speakers capable of playing CD quality music and sounds with the Sound Blaster sound card on PCs.

ThinkPad

IBM introduced its successful ThinkPad range at COMDEX 1992 using the series designators 300, 500 and 700 (allegedly analogous to the BMW car range and used to indicate market), the 300 series being the "budget", the 500 series "midrange" and the 700 series "high end". This designation continued until the late 1990s when IBM introduced the "T" series as 600/700 series replacements, and the 3, 5 and 7 series model designations were phased out for A (3&7) & X (5) series. The A series was later partially replaced by the R series.

Dell

By the mid-1990s, Amiga, Commodore and Atari systems were no longer on the market, pushed out by strong IBM PC clone competition and low prices. Other previous competition such as Sinclair and Amstrad were no longer in the computer market. With less competition than ever before, Dell rose to high profits and success, introducing low cost systems targeted at consumers and business markets using a direct-sales model. Dell surpassed Compaq as the world's largest computer manufacturer, and held that position until October 2006.

Power Macintosh, PowerPC

In 1994, Apple introduced the Power Macintosh series of high-end professional desktop computers for desktop publishing and graphic designers. These new computers made use of new Motorola PowerPC processors as part of the AIM alliance, to replace the previous Motorola 68k architecture used for the Macintosh line. During the 1990s, the Macintosh remained with a low market share, but as the primary choice for creative professionals, particularly those in the graphics and publishing industries.

Risc PC

Also in 1994, Acorn Computers launched its Risc PC series of high-end desktop computers. The Risc PC (codenamed Medusa) was Acorn's next generation ARM-based RISC OS computer, which superseded the Acorn Archimedes.

IBM clones, Apple back into profitability

Due to the sales growth of IBM clones in the '90s, they became the industry standard for business and home use. This growth was augmented by the introduction of Microsoft's Windows 3.0 operating environment in 1990, and followed by Windows 3.1 in 1992 and the Windows 95 operating system in 1995. The Macintosh was sent into a period of decline by these developments coupled with Apple's own inability to come up with a successor to the Macintosh operating system, and by 1996 Apple was almost bankrupt. In December 1996 Apple bought NeXT and in what has been described as a "reverse takeover", Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997. The NeXT purchase and Jobs' return brought Apple back to profitability, first with the release of Mac OS 8, a major new version of the operating system for Macintosh computers, and then with the PowerMac G3 and iMac computers for the professional and home markets. The iMac was notable for its transparent bondi blue casing in an ergonomic shape, as well as its discarding of legacy devices such as a floppy drive and serial ports in favor of Ethernet and USB connectivity. The iMac sold several million units and a subsequent model using a different form factor remains in production as of August 2017. In 2001 Mac OS X, the long-awaited "next generation" Mac OS based on the NeXT technologies was finally introduced by Apple, cementing its comeback.

Writable CDs, MP3, P2P file sharing

The ROM in CD-ROM stands for Read Only Memory. In the late 1990s CD-R and later, rewritable CD-RW drives were included instead of standard CD ROM drives. This gave the personal computer user the capability to copy and "burn" standard Audio CDs which were playable in any CD player. As computer hardware grew more powerful and the MP3 format became pervasive, "ripping" CDs into small, compressed files on a computer's hard drive became popular. "Peer to peer" file sharing networks such as Napster, Kazaa and Gnutella arose to be used almost exclusively for sharing music files and became a primary computer activity for many individuals.

USB, DVD player

Since the late 1990s, many more personal computers started shipping that included USB (Universal Serial Bus) ports for easy plug and play connectivity to devices such as digital cameras, video cameras, personal digital assistants, printers, scanners, USB flash drives and other peripheral devices. By the early 21st century, all shipping computers for the consumer market included at least two USB ports. Also during the late 1990s DVD players started appearing on high-end, usually more expensive, desktop and laptop computers, and eventually on consumer computers into the first decade of the 21st century.

Hewlett-Packard

In 2002, Hewlett-Packard (HP) purchased Compaq. Compaq itself had bought Tandem Computers in 1997 (which had been started by ex-HP employees), and Digital Equipment Corporation in 1998. Following this strategy HP became a major player in desktops, laptops, and servers for many different markets. The buyout made HP the world's largest manufacturer of personal computers, until Dell later surpassed HP.

64 bits

In 2003, AMD shipped its 64-bit based microprocessor line for desktop computers, Opteron and Athlon 64. Also in 2003, IBM released the 64-bit based PowerPC 970 for Apple's high-end Power Mac G5 systems. Intel, in 2004, reacted to AMD's success with 64-bit based processors, releasing updated versions of their Xeon and Pentium 4 lines. 64-bit processors were first common in high end systems, servers and workstations, and then gradually replaced 32-bit processors in consumer desktop and laptop systems since about 2005.

Lenovo

In 2004, IBM announced the proposed sale of its PC business to Chinese computer maker Lenovo Group, which is partially owned by the Chinese government, for US$650 million in cash and $600 million US in Lenovo stock. The deal was approved by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States in March 2005, and completed in May 2005. IBM will have a 19% stake in Lenovo, which will move its headquarters to New York State and appoint an IBM executive as its chief executive officer. The company will retain the right to use certain IBM brand names for an initial period of five years. As a result of the purchase, Lenovo inherited a product line that featured the ThinkPad, a line of laptops that had been one of IBM's most successful products.

Wi-Fi, LCD monitor, flash memory

In the early 21st century, Wi-Fi began to become increasingly popular as many consumers started installing their own wireless home networks. Many of today's laptops and desktop computers are sold pre-installed with wireless cards and antennas. Also in the early 21st century, LCD monitors became the most popular technology for computer monitors, with CRT production being slowed down. LCD monitors are typically sharper, brighter, and more economical than CRT monitors. The first decade of the 21st century also saw the rise of multi-core processors (see following section) and flash memory. Once limited to high-end industrial use due to expense, these technologies are now mainstream and available to consumers. In 2008 the MacBook Air and Asus Eee PC were released, laptops that dispense with an optical drive and hard drive entirely relying on flash memory for storage.

Local area networks

The invention in the late 1970s of local area networks (LANs), notably Ethernet, allowed PCs to communicate with each other (peer-to-peer) and with shared printers.

As the microcomputer revolution continued, more robust versions of the same technology were used to produce microprocessor based servers that could also be linked to the LAN. This was facilitated by the development of server operating systems to run on the Intel architecture, including several versions of both Unix and Microsoft Windows.

Multiprocessing

In May 2005, AMD and Intel released their first dual-core 64-bit processors, the Pentium D and the Athlon 64 X2 respectively. Multi-core processors can be programmed and reasoned about using symmetric multiprocessing (SMP) techniques known since the 60s (see the SMP article for details).

Apple switches to Intel in 2006, also thereby gaining multiprocessing.

In 2013, a Xeon Phi extension card is released with 57 x86 cores, at a price of $1695, equalling circa 30 dollars per core.

ARM

In 2005, the ARM Cortex-A8 is released, the first Cortex design to be adopted on a large scale for use in consumer devices.[67] An ARM core is later used in the Raspberry Pi, a very cheap minicomputer.

PCI-E

PCI Express is released in 2003. It becomes the most commonly used bus in PC-compatible desktop computers.

Cheap 3D graphics

The rise of cheap 3D accelerators displaced low-end products of Silicon Graphics (SGI), which went bankrupt in 2009.

Silicon Graphics was a major 3D business that had grown annual revenues of $5.4 million to $3.7 billion from 1984 to 1997.[68]

The addition of 3D graphic capabilities to PCs, and the ability of clusters of Linux- and BSD-based PCs to take on many of the tasks of larger SGI servers, ate into SGI's core markets.

Three former SGI employees had founded 3dfx in 1994. Their Voodoo Graphics extension card relied on PCI to provide cheap 3D graphics for PC's. Towards the end of 1996, the cost of EDO DRAM dropped significantly. A card consisted of a DAC, a frame buffer processor and a texture mapping unit, along with 4 MB of EDO DRAM. The RAM and graphics processors operated at 50 MHz. It provided only 3D acceleration and as such the computer also needed a traditional video controller for conventional 2D software.

NVIDIA bought 3dfx in 2000. In 2000, NVIDIA grew revenues 96%.[69]

SGI had made OpenGL. Control of the specification was passed to the Khronos Group in 2006.

SDRAM

In 1993, Samsung introduced its KM48SL2000 synchronous DRAM, and by 2000, SDRAM had replaced virtually all other types of DRAM in modern computers, because of its greater performance. For more information see Synchronous dynamic random-access memory#SDRAM history.

Double data rate synchronous dynamic random-access memory (DDR SDRAM) is introduced in 2000.

Compared to its predecessor in PC-clones, single data rate (SDR) SDRAM, the DDR SDRAM interface makes higher transfer rates possible by more strict control of the timing of the electrical data and clock signals.

ACPI

Released in December 1996, ACPI replaced Advanced Power Management (APM), the MultiProcessor Specification, and the Plug and Play BIOS (PnP) Specification.[70]

Internally, ACPI advertises the available components and their functions to the operating system kernel using instruction lists ("methods") provided through the system firmware (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) or BIOS), which the kernel parses. ACPI then executes the desired operations (such as the initialization of hardware components) using an embedded minimal virtual machine.

First-generation ACPI hardware had issues.[71] Windows 98 first edition disabled ACPI by default except on a whitelist of systems.

2010s

Semiconductor fabrication

In 2011, Intel announces the commercialisation of Tri-gate transistor.[72] The Tri-Gate design is a variant of the FinFET 3D structure. FinFET was developed in the 1990s by Chenming Hu and his colleagues at UC Berkeley.[73]

Through-silicon via is used in High Bandwidth Memory (HBM), a successor of DDR-SDRAM. HBM was released in 2013.

In 2016 and 2017, Intel, TSMC and Samsung begin releasing 10 nanometer chips. At the ≈10 nm scale, quantum tunneling (especially through gaps) becomes a significant phenomenon.[74]

Market size

In 2001, 125 million personal computers were shipped in comparison to 48,000 in 1977. More than 500 million PCs were in use in 2002 and one billion personal computers had been sold worldwide since mid-1970s till this time. Of the latter figure, 75 percent were professional or work related, while the rest sold for personal or home use. About 81.5 percent of PCs shipped had been desktop computers, 16.4 percent laptops and 2.1 percent servers. United States had received 38.8 percent (394 million) of the computers shipped, Europe 25 percent and 11.7 percent had gone to Asia-Pacific region, the fastest-growing market as of 2002.[75] Almost half of all the households in Western Europe had a personal computer and a computer could be found in 40 percent of homes in United Kingdom, compared with only 13 percent in 1985.[76] The third quarter of 2008 marked the first time laptops outsold desktop PCs in the United States.[77]

As of June 2008, the number of personal computers worldwide in use hit one billion. Mature markets like the United States, Western Europe and Japan accounted for 58 percent of the worldwide installed PCs. About 180 million PCs (16 percent of the existing installed base) were expected to be replaced and 35 million to be dumped into landfill in 2008. The whole installed base grew 12 percent annually.[78][79]

See also

- Timeline of electrical and electronic engineering

- Computer museum and Personal Computer Museum

- Expensive Desk Calculator

- MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory

- Educ-8 a 1974 pre-microprocessor "micro-computer"

- Mark-8, a 1974 microprocessor-based microcomputer

- Programma 101, a 1965 programmable calculator with some attributes of a personal computer

- SCELBI, another 1974 microcomputer

- Simon (computer), a 1949 demonstration of computing principles

- List of pioneers in computer science

References

- "Pocket Computer May Replace Shopping List". The New York Times. 3 November 1962.

- "9100A desktop calculator, 1968" (PDF). Hewlett-Packard. Retrieved 13 February 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hewlett-Packard (25 October 1966). "Restoring the Balance between Analysis and Computation" (PDF). Science Magazine. 169 (3852): 409. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- Shapiro, F.R.; Shapiro, F.R. (December 2000). "Annals of the History of Computing". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. IEEE Journal. 22 (4): 70–71. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2000.887997.

- Helmers, Carl (October 1975). "What is BYTE". BYTE. pp. 4, col 3, para 2. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- Horn, B.; Winston, P. (May 1975). "Personal Computers". Datamation. p. 11. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- "Most Important Companies". Byte. September 1995. Archived from the original on 18 June 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- "Birth of an Industry 1976–77". Apple Computer Inc. advertisements. Kelley Advertising and Marketing. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2008.

Introducing Apple II. You've just run out of excuses for not owning a personal computer.

- "Oldest Known Commodore PET Brochure". Archived from the original on 29 April 2006. Retrieved 14 June 2008.

- Reimer, Jeremy (14 December 2005). "Total share: 30 years of personal computer market share figures; The 8-bit era (1980–1984)". Ars Technica. p. 4. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- Anthony Ralston and Edwin D. Reilly (ed), Encyclopedia of Computer Science 3rd Edition, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1993 ISBN 0-442-27679-6, article Digital Computers History

- Rheingold, H. (2000). Tools for thought: the history and future of mind-expanding technology (New ed.). Cambridge, MA etc.: The MIT Press.

- Colinge, Jean-Pierre; Greer, James C. (2016). Nanowire Transistors: Physics of Devices and Materials in One Dimension. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9781107052406.

- "1960 - Metal Oxide Semiconductor (MOS) Transistor Demonstrated". The Silicon Engine. Computer History Museum.

- Lojek, Bo (2007). History of Semiconductor Engineering. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 321–3. ISBN 9783540342588.

- "Who Invented the Transistor?". Computer History Museum. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- Hittinger, William C. (1973). "Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Technology". Scientific American. 229 (2): 48–59. Bibcode:1973SciAm.229b..48H. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0873-48. ISSN 0036-8733. JSTOR 24923169.

- "1971: Microprocessor Integrates CPU Function onto a Single Chip". Computer History Museum. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "The IBM 610 Auto-Point Computer". Columbia University.

- What was the first personal computer? at Blinkenlights Archaeological Institute. Accessed: 15 March 2008.

- http://www.digibarn.com/stories/linc/documents/LINC-Personal-Workstation/LINC-Personal-Workstation.pdf LINC Personal Workstation, retrieved 26 May 2018

- "Olivetti Programma P101/P102". old-computers.com. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

The Programma P101 may be considered as the first programmable electronic desk top calculator in the world.

- Computer History Museum , Timeline of Computer History, Olivetti Programma 101 is released

- "2008/107/1 Computer, Programma 101, and documents (3), plastic / metal / paper / electronic components, hardware architect Pier Giorgio Perotto, designed by Mario Bellini, made by Olivetti, Italy, 1965-1971". www.powerhousemuseum.com. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "Olivetti Programma 101 Electronic Calculator". The Old Calculator Web Museum.

technically, the machine was a programmable calculator, not a computer.

- "Olivetti Programma 101 Electronic Calculator". The Old Calculator Web Museum.

It appears that the Mathatronics Mathatron calculator preceeded the Programma 101 to market.

- "Olivetti Programma P101/P102". old-computers.com. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

There were neither microprocessor (not yet invented) nor integrated circuits in the P101, but only transistors, resistors and condensers.

- "---+ 1000 BiT +--- Computer's description". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- "Olivetti Programma P101/P102". old-computers.com. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

The P101, and particularly the magnetic card, was covered by a US patent (3,495,222, Perotto et al.) and this gave to Olivetti over $900.000 in royalties by HP alone, for the re-use of this technology in the HP9100 series.

- Perotto, Pier Giorgio; et al. (10 February 1970). "3,495,222 PROGRAM CONTROLLED ELECTRONIC COMPUTER" (multiple). United States Patent Office. Google patents. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- Pospelov, Dmitry. ЭВМ серии МИР - первые персональные ЭВМ [MIR series of computers. The first personal computers]. Glushkov Foundation (in Russian). Institute of Applied Informatics. Archived from the original on 24 November 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- Marek Kępa, The Computer Genius the Communists Couldn't Stand, culture.pl, Aug 7 2017

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 May 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link);

- A History of Modern Computing, (MIT Press), pp. 220–21

- Koved, Larry; Selker, Ted (1999). "Room with a view (RWAV): A metaphor for interactive computing". IBM TJ Watson Research Center. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.22.1340. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Thacker, Charles P., et al. Alto: A personal computer. Xerox, Palo Alto Research Center, 1979.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- IBM Archives

- Friedl, Paul J. (November 1983). "SCAMP: The Missing Link In The PC's Past?". PC. pp. 190–197. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- Chandler, Alfred Dupont; Hikino, Takashi; Nordenflycht, Andrew Von; Chandler, Alfred D. (30 June 2009). Inventing the Electronic Century. ISBN 9780674029392. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- Schuyten, Peter J. (6 December 1978). "Technology; The Computer Entering Home". Business & Finance. The New York Times. p. D4. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "Most Important Companies". Byte. September 1995. Archived from the original on 18 June 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- http://museum.ipsj.or.jp/en/computer/personal/0087.html

- Reimer, Jeremy (14 December 2005). "Total share: 30 years of personal computer market share figures; The new era (2001– )". Ars Technica. p. 9. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- Reimer, Jeremy (December 2005). "Personal Computer Market Share: 1975–2004". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 6 June 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- Lemmons, Phil (November 1982). "Chuck Peddle: Chief Designer of the Victor 9000" (PDF). Byte Magazine. Retrieved 14 June 2008.

- What's New (February 1978). "Commodore Ships First PET Computers". BYTE. Byte Publications. 3 (2): 190. Commodore press release. "The PET computer made its debut recently as the first 100 units were shipped to waiting customers in mid October 1977."

- Veit, Stan. "TRS-80 the "Trash-80"". pc-history.org.

- Helmers, Carl (January 1980). "The Era of Off-the-Shelf Personal Computers Has Arrived". BYTE. pp. 6–10, 93–98.

- Hogan, Thom (31 August 1981). "From Zero to a Billion in Five Years". InfoWorld. pp. 6–7. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- Kahney, Leander (9 September 2003). "Grandiose Price for a Modest PC". Wired. Lycos. Retrieved 25 October 2006.

- Williams, Gregg; Welch, Mark; Avis, Paul (September 1985). "A Microcomputing Timeline". BYTE. p. 198. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- Ahl, David H. (1984 November). The first decade of personal computing. Creative Computing, vol. 10, no. 11: p. 30.

- Pollack, Andrew (19 June 1983). "The Coming Crisis in Home Computers". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- Mitchell, Peter W. (6 September 1983). "A summer-CES report". Boston Phoenix. p. 4. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- Anderson, John J. (March 1984). "Commodore". Creative Computing. p. 56. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- Bisson, Gigi (May 1986). "Antic Then & Now". Antic. pp. 16–23. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- Lock, Robert (June 1983). "Editor's Notes". Compute!. p. 6. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Lock, Robert C. (January 1986). "Editor's Notes". Compute's Gazette. p. 6.

- Szczepaniak, John. "Retro Japanese Computers: Gaming's Final Frontier". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved 29 March 2011. Reprinted from Retro Gamer, 2009

- "Computing Japan". Computing Japan. LINC Japan. 54-59: 18. 1999. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

...its venerable PC 9800 series, which has sold more than 18 million units over the years, and is the reason why NEC has been the number one PC vendor in Japan for as long as anyone can remember.

- A.Audsley. "The Old Computer Hut - Intel family microcomputers (1)". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Reimer, Jeremy (14 December 2005). "Total share: 30 years of personal computer market share figures; The rise of the PC (1987–1990)". Ars Technica. p. 6. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- Gupta, Rahul (26 April 2013). "ARM Cortex: The force that drives mobile devices". The Mobile Indian. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Einstein, David (29 October 1997). "McCracken leaves SGI; 700 to 1000 laid off". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- http://www.nvidia.com/object/IO_20010816_4361.html

- "ACPI Overview" (slide show in PDF). www.acpi.info.

- "Cover Story: Win98 Bugs & Fixes - December 1998". winmag.com. Archived from the original on 13 October 1999.

- Shimpi, Anand Lal (4 May 2011). "Intel Announces first 22nm 3D Tri-Gate Transistors, Shipping in 2H 2011". AnandTech. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- http://www.nature.com/news/2011/110506/full/news.2011.274.html

- Naitoh, Y.; et al. (2007). "New Nonvolatile Memory Effect Showing Reproducible Large Resistance Ratio Employing Nano-gap Gold Junction". MRS Proceedings. 997: 0997–I04–08. doi:10.1557/PROC-0997-I04-08.

- "PCs: More than 1 billion served". CNET. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- "BBC NEWS - Science/Nature - Computers reach one billion mark". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- Notebook sales surpass PCs for first time in US Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Gartner Says More than 1 Billion PCs In Use Worldwide and Headed to 2 Billion Units by 2014". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- "Computers in use pass 1 billion mark: Gartner". Reuters. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

Further reading

- Veit, Stan (1993). Stan Veit's History of the Personal Computer. WorldComm. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-56664-030-5.

- Douglas K. Smith; Douglas K. Smith; Robert C. Alexander (1999). Fumbling the Future: How Xerox Invented, then Ignored, the First Personal Computer. Authors Choice Press. pp. 276. ISBN 978-1-58348-266-7.

- Freiberger, Paul; Swaine, Michael (2000). Fire in the Valley: The Making of The Personal Computer. McGraw-Hill Companies. pp. 463. ISBN 978-0-07-135892-7.

- Allan, Roy A. (2001). A History of the Personal Computer: The People and the Technology. Allan Publishing. p. 528. ISBN 978-0-9689108-0-1.

- Sherman, Josepha (2003). The History of the Personal Computer. Franklin Watts. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-531-16213-2.

- Laing, Gordon (2004). Digital Retro: The Evolution and Design of the Personal Computer. Sybex. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-7821-4330-0.

External links

- A history of the personal computer: the people and the technology (PDF)

- BlinkenLights Archaeological Insititute – Personal Computer Milestones

- Personal Computer Museum – A publicly viewable museum in Brantford, Ontario, Canada

- Old Computers Museum – Displaying over 100 historic machines.

- Chronology of Personal Computers – a chronology of computers from 1947 on

- "Total share: 30 years of personal computer market share figures"

- Obsolete Technology – Old Computers