Valladolid

Valladolid (/ˌvælədəˈliːd, -ˈlɪd, ˌbɑːjə-/, Spanish: [baʎaðoˈlið] (![]()

Valladolid | |

|---|---|

_Ricardo_Bl%C3%A1zquez_visita_la_Torre_Sur_de_la_Catedral_10_(19169822978)_(cropped).jpg) | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

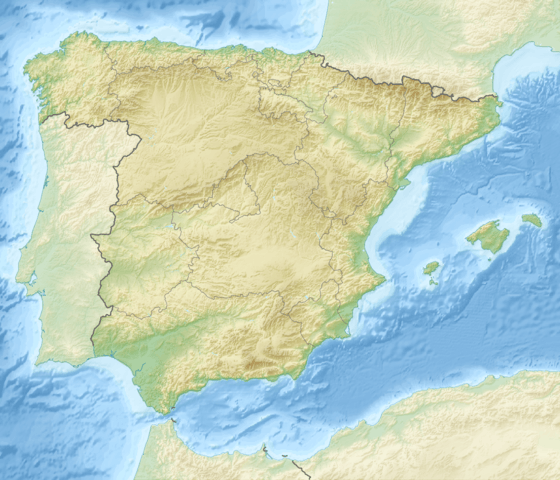

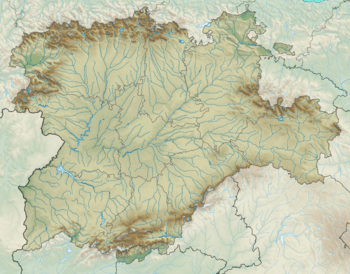

Valladolid Location of Valladolid within Spain / Castile and León  Valladolid Valladolid (Castile and León)  Valladolid Valladolid (Europe) | |

| Coordinates: 41°39′10″N 4°43′25″W | |

| Country | Spain |

| Autonomous community | Castile and León |

| Province | Valladolid |

| Founded | 1072 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Óscar Puente (2015) (PSOE) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 197.91 km2 (76.41 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 698 m (2,290 ft) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

| • Total | 298,866 |

| • Density | 1,500/km2 (3,900/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Vallisoletano, -a (informally, pucelano, -a) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 47001–47016 |

| Dialing code | 983 |

| Official language(s) | Spanish |

| Patron saint | Saint Peter de Regalado |

| Website | Official website |

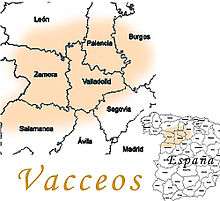

The city is situated at the confluence of the Pisuerga and Esgueva rivers 15 km (9.3 mi) before they join the Duero, and located within five winegrowing regions: Ribera del Duero, Rueda, Toro, Tierra de León, and Cigales. Valladolid was originally settled in pre-Roman times by the Celtic Vaccaei people, and later the Romans themselves. It remained a small settlement until being re-established by King Alfonso VI of Castile as a Lordship for the Count Pedro Ansúrez in 1072. It grew to prominence in the Middle Ages as the seat of the Court of Castile and being endowed with fairs and different institutions as a collegiate church, University (1241), Royal Court and Chancery and the Royal Mint. The Catholic Monarchs, Isabel I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, married in Valladolid in 1469 and established it as the capital of the Kingdom of Castile and later of united Spain. Christopher Columbus died in Valladolid in 1506, while authors José Zorrilla, Miguel de Cervantes and Francisco de Quevedo lived and worked in the city. The city was briefly the capital of Habsburg Spain under Phillip III between 1601 and 1606, before returning indefinitely to Madrid. The city then declined until the arrival of the railway in the 19th century, and with its industrialisation into the 20th century.

The old town is made up of a variety of historic houses, palaces, churches, plazas, avenues and parks, and includes the National Museum of Sculpture, the Museum of Contemporary Art Patio Herreriano or the Oriental Museum, as well as the houses of Zorrilla and Cervantes which are open as museums. Among the events that are held each year in the city are the famous Holy Week, Valladolid International Film Festival (Seminci), and the Festival of Theatre and Street Arts (TAC).

Etymology

There is no direct evidence for the origin of the modern name of Valladolid. One widely held etymological theory suggests that the modern name Valladolid derives from the Celtiberian language expression Vallis Tolitum, meaning "valley of waters", referring to the confluence of rivers in the area. Another theory suggests that the name derives from the Arabic expression (Arabic: بلد الوليد, romanized: Balad al-Walid), which means "city of al-Walid", referring to Al-Walid I.[3][4] Yet a third claims that it derives from Vallis Olivetum, meaning "valley of the olives"; however, no olive trees are found in that terrain. Instead, in the south part of the city exist an innumerable amount of pine trees. The gastronomy reflects the importance of the piñon (pine nut) as a local product, not olives. In texts from the middle ages the town is called Vallisoletum, meaning "sunny valley", and a person from the town is a Vallisoletano (male), o Vallisoletana (female).

The city is also popularly called Pucela, a nickname whose origin is not clear, but may refer to knights in the service of Joan of Arc, known as La Pucelle. Another theory is that Pucela comes from the fact that Pozzolana cement was sold there, the only city in Spain that sold it.

Geography

Valladolid is located at roughly 735 metres above sea level, at the centre of the Meseta Norte,[5] the plateau drained by the Douro river basin covering a major part of the Northwest of the Iberian Peninsula. The city of Valladolid lies on both banks of the Pisuerga River, a major right-bank tributary of the Douro.

Climate

The city of Valladolid experiences a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Csa) with influences of a cold semi-arid climate (BSk). Valladolid's climate features cool and windy winters due to altitude and an inland location. Fog is very typical. Winters experience snow and low temperatures below freezing during cold fronts. Valladolid's climate is influenced by the distance from the sea and its higher altitude.

Temperature ranges can be extreme and Valladolid is drier than Spain's northern coastal regions, although there is year-round precipitation. Average annual precipitation is 435 mm (17,12 in) and the average annual relative humidity is 65%. In winter, temperatures very often (almost every second day) drop below freezing, often reaching temperatures as low as −8 °C or 17.6 °F, and snowfall is common, while the summer months see average high temperatures of 30 °C or 86 °F. The lowest recorded temperature in Valladolid was −18.8 °C or −1.8 °F and the hottest 40.2 °C or 104.36 °F on 19 July 1995.

| Climate data for Valladolid (1981–2010) Extremes (1971–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.2 (63.0) |

23.6 (74.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

29.7 (85.5) |

34.4 (93.9) |

37.6 (99.7) |

40.2 (104.4) |

39.5 (103.1) |

38.2 (100.8) |

30.2 (86.4) |

23.2 (73.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

40.2 (104.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.2 (46.8) |

11.2 (52.2) |

15.2 (59.4) |

16.9 (62.4) |

21.0 (69.8) |

27.0 (80.6) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.1 (86.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

18.9 (66.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

8.6 (47.5) |

18.8 (65.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

5.9 (42.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.1 (71.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

7.9 (46.2) |

5.0 (41.0) |

12.7 (54.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.2 (32.4) |

0.7 (33.3) |

2.8 (37.0) |

4.6 (40.3) |

7.9 (46.2) |

11.6 (52.9) |

14.0 (57.2) |

14.1 (57.4) |

11.3 (52.3) |

7.6 (45.7) |

3.5 (38.3) |

1.3 (34.3) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −18.8 (−1.8) |

−16 (3) |

−12.4 (9.7) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

2.4 (36.3) |

2.4 (36.3) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

−18.8 (−1.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 40 (1.6) |

27 (1.1) |

22 (0.9) |

46 (1.8) |

49 (1.9) |

29 (1.1) |

13 (0.5) |

16 (0.6) |

31 (1.2) |

55 (2.2) |

52 (2.0) |

53 (2.1) |

433 (17.0) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 68 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83 | 72 | 62 | 62 | 60 | 52 | 45 | 48 | 56 | 70 | 79 | 84 | 64 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 101 | 147 | 215 | 232 | 272 | 322 | 363 | 334 | 254 | 182 | 117 | 89 | 2,624 |

| Source 1: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología (normals 1981–2010)[6] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología (extremes only 1938–2012)[7] | |||||||||||||

History

The Vaccaei were a Celtic tribe, the first people with stable presence on the sector of the middle valley of the River Duero documented in historical times.

Remains of Celtiberian and of a Roman camp have been excavated near the city. The nucleus of the city was originally located in the area of the current San Miguel y el Rosarillo square and was surrounded by a palisade. Archaeological proofs of the existence of three ancient lines of walls have been found.

During the time of Muslim rule in Spain, the Christian kings moved the population of this region north into more easily defended areas and deliberately created a no man's land as a buffer zone against further Moorish conquests. The area was captured from the Moors in the 10th century, and Valladolid was a village until King Alfonso VI of León and Castile donated it to Count Pedro Ansúrez in 1072. He built a palace (now lost) for himself and his wife, Countess Eylo, the Collegiate of St. Mary and the La Antigua churches. In the 12th and 13th centuries, Valladolid grew rapidly, thanks also to the commercial privileges granted by the kings Alfonso VIII and Alfonso X, as well as to the repopulation of the area after the Reconquista.

In 1469, Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand of Aragon were married in the city; by the 15th century Valladolid was the residence of the kings of Castile. In 1506, Christopher Columbus died in Valladolid "still convinced that he had reached the Indies"[8] in a house that is now a museum dedicated to him.

From 1554 to 1559, Joanna of Austria, sister of Philip II, served as regent, establishing herself in Valladolid,[9] with the latter becoming the political center of the Hispanic Monarchy by that time.[10] She favoured the Ebolist Party, one of the two leading factions of the Court of Philip II, in competition with the albistas.[9] The Reformation took some hold in the city appearing some Protestant circles presumably around the leading figure of Augustino de Cazalla, an adviser of Joanna.[10] Ensuing autos de fe against the Protestant sects took place in 1559 in Valladolid.[10] A catastrophic fire in 1561 destroyed a portion of the city.[11]

Valladolid was granted the status of city in 1596, also becoming a bishopric seat.[12]

In the midst of the reign of by Philip III, Valladolid briefly served as the capital of the Hispanic Monarchy between 1601 and 1606 under the auspice of the Duke of Lerma, valido of Philip III. Lerma and his network had bought plots in Valladolid before in order to sell those to the Crown.[13] Promoted by Lerma, the decision on moving the capital from Madrid to Valladolid has been portrayed as case of a (double) real estate speculative scheme, as Lerma had proceeded to buy housing in Madrid once the capital was moved from the city as the prices had plummeted.[14][13] After a plague epidemics in Valladolid, Lerma suggested the King to go back to Madrid, earning a hefty profit when the Royal Court went back to Madrid and the prizes went up again accordingly.[14][13]

The city was again damaged by a flood of the rivers Pisuerga and Esgueva.

Despite the damage caused in the old city by the 1960s economic boom, it still boasts a few architectural manifestations of its former glory. Some monuments include the unfinished cathedral, the Plaza Mayor (Main Square), which was the model for that of Madrid, and of other main squares throughout the former Spanish Empire, the National Sculpture Museum, next to the church of Saint Paul, which includes Spain's greatest collections of polychrome wood sculptures, and the Faculty of Law of the University of Valladolid, whose façade is one of the few surviving works by Narciso Tomei, the same artist who did the transparent in Toledo Cathedral. The Science Museum is next to the river Pisuerga. The only surviving house of Miguel de Cervantes is also located in Valladolid. Although unfinished, the Cathedral of Valladolid was designed by Juan de Herrera, the architect of El Escorial.

Education

Education in Valladolid depends on the Ministry of Education of the Government of Castile and Leon, the department responsible for the education at the regional level, both at the university and non-university level. According to the department itself, an estimated in the academic year 2005–2006 the total number of university students was not more than 52 000, which are available to 141 schools, with 2399 and 4487 classroom teachers.

Universities

University of Valladolid

The University of Valladolid (UVA) was founded in 1241. It is one of the oldest universities in the world. It has four campuses around the city (Huerta del Rey, Centro, Río Esgueva and Miguel Delibes) as well as another three campuses scattered around the wider region of Castile and León (Palencia, Soria and Segovia). Spread over 25 colleges and their associated centers, about 2000 teachers give classes to more than 23,800 students enrolled in 2011.

It also features the 25 centers, a number of administrative buildings such as the Palacio de Santa Cruz, where the rector, and the Museum of the University of Valladolid (MUVa), The Student House, featuring the other administrative services, or CTI (Center for Information Technology), located in the basement of the University Residence Alfonso VIII, next to the old Faculty of Science.

Miguel de Cervantes European University

The Miguel de Cervantes European University (Universidad Europea Miguel de Cervantes; UEMC) is a private university with roughly 1,500 students. It is spread over three faculties: Social Sciences, Law and Economics, Health and the Polytechnic School. It has later expanded its campus with a new facility doubling the area devoted to teaching and research. It also has a dental clinic and a library.

Primary and secondary schools

Lycée Français de Castilla y León, a French international school, is near Valladolid, in Laguna de Duero.[15] San Juán Bautista de La Salle School, a High Private College in Valladolid. Integral and Superior Education. Integrates Kindergarten, Primary School and High School.[16]

Main sights

The capital of Castile y León preserves in its old quarter its heritage of aristocratic houses and religious buildings.

Religious buildings

- The unfinished Cathedral, commissioned by King Philip II and designed by the architect Juan de Herrera in the 16th century, following a Mannerist style perhaps influenced by Michelangelo. The church is unfinished owing to financial problems and its nave was not opened until 1668. Years later, in 1730, Master Churriguera finished the work on the main front. Inside the cathedral, the sanctuary houses a reredos made by Juan de Juni in 1562. The complex is linked to the Diocesan Museum, which holds carvings attributed to Gregorio Fernández and Juni himself, as well as a silver monstrance by Juan de Arce.

- The large Gothic church of San Benito, built by the Benedictines between 1500 and 1515, with an unusual tower.

- San Miguel Church, ancient church of the Jesuits (now a parish church), built at the end of the 16th century, hosts some reredos by the early 17th-century sculptor Gregorio Fernández.

- The façade of the Dominican Church of San Pablo, characterized by Gothic statues and decoration built around 1500.

- El Salvador Church, with a façade built around 1550, a 15th-century Flemish reredos and a brick tower dating from the 17th century.

- The church of Santiago has reredos depicting the Adoration of the Magi (1537) created by Berruguete and, in the sanctuary, a great Baroque reredos depicting Saint James killing Moors, as is common in Spain.

- The Gothic church of Santa María la Antigua has an unusual pyramid-shaped Romanesque tower from the 12th century and a 14th-century Gothic sanctuary, influenced by the Cathedral of Burgos.

- The Cistercian Convent of Santa María la Real de las Huelgas, originally built about 1600, following Spanish Mannerist tendencies.

- The Convento de Santa Ana, a Neoclassical building housing various paintings by Francisco de Goya.

- San Juan de Letrán Church, featuring a Baroque façade built-in 1737. Beside this church is the Monasterio de Los Padres Filipinos, designed by the architect Ventura Rodríguez in 1760.

Other buildings

The heart of the old city is the 16th-century Plaza Mayor, presided over by a statue of Count Ansúrez from 1903. On one side of it stands the City Hall, an eclectic building dating from the beginning of the 20th century, crowned by a clock tower. In the nearby streets is the Palacio de Pimentel (Pimental Palace), today the seat of the Provincial Council. It is one of the most important palaces, as King Philip II was born here on 21 May 1527. The Royal Palace (where King Philip IV of Spain and Queen Anne of France, mother of Louis XIV were born), the 16th-century Palace of the Marquises of Valverde, and that of the banker Fabio Nelli – a building with a Classicist stamp built in 1576 – should also be pointed out. The Museum of Valladolid occupies this complex, exhibiting a collection of furniture, sculptures, paintings and ceramic pieces dated from Prehistoric times to the present.

The Teatro Lope de Vega is a theater built in the classical style in 1861 and now very run-down. There has been controversy over whether the city should pay to restore it.[17]

The Campo Grande, a large public park located in the heart of the city, dates back to 1787.

The National Sculpture Museum is site in Colegio de San Gregorio, an Isabelline style building. It is home to polychrome carvings made by artists like Alonso Berruguete or Gregorio Fernández. The Museum of Contemporary Spanish Art, located in the Patio Herreriano, one of the cloisters of the former Monastery of San Benito, preserves more than 800 paintings and sculptures from the 20th century.

The University, whose Baroque façade is decorated with various academic symbols, and the Santa Cruz College, which as well as housing a library forms one of the first examples of the Spanish Renaissance.

The city preserves houses where great historical characters once lived. They include:

- the Casa de Cervantes, where the author of Don Quijote lived with his family between 1603 and 1606. It was in this house where the writer finished his masterpiece.

- The Christopher Columbus House-Museum is located in what is thought to be the residence of the Genoese navigator in the last years of his life. Nowadays the palace exhibits various pieces and documents related to the discovery of America.

- The house where José Zorrilla was born, housing various personal possessions, furniture and documents that belonged to the Romantic writer.

Population

As of the 2013 census, the population of the city of Valladolid proper was 309,714,[2] and the population of the entire urban area was estimated to be near 420,000. The most important municipalities of the urban area are (after Valladolid itself) Laguna de Duero and Boecillo on the south, Arroyo de la Encomienda, Zaratán, Simancas and Villanubla on the west, Cigales and Santovenia de Pisuerga on the north, and Tudela de Duero and Cistérniga on the east.

After the new neighbourhoods developed in recent decades (one example would be Covaresa) the high prices in the municipality led young people to buy properties in towns around the city, so the population has tended to fall in Valladolid but is growing fast in the rest of the urban area (for example, Arroyo de la Encomienda or Zaratán)

Economy

Valladolid is a major economic center in Spain. The automotive industry is one of the major motors of the city's economy since the founding of FASA-Renault in 1953 for the assembling of Renault-branded vehicles, which would later become Renault España. Four years later, in 1957, Sava was founded and started producing commercial vehicles. Sava would later be absorbed by Pegaso and since 1990 by the Italian truck manufacturer Iveco. Together with the French tire manufacturer Michelin, Renault and Iveco form the most important industrial companies of the city.

Besides the automotive and automotive auxiliary industries, other important industrial sectors are food processing (with local companies like Acor and Queserías Entrepinares and facilities of multinationals like Cadbury, Lactalis or Lesaffre), metallurgy (Lingotes Especiales, Saeta die Casting...), chemical and printing. In total 22 013 people were employed in 2007 in industrial workplaces, representing 14.0% of total workers.[18]

The main economic sector of Valladolid in terms of employment is however the service sector, which employs 111,988 people, representing 74.2% of Valladolid workers affiliated to Social Security.

The construction sector employed 15,493 people in 2007, representing 10.3% of total workers.

Finally, agriculture is a tiny sector in the city which only employs 2,355 people (1.5% of the total). The predominant crops are wheat, barley and sugar beet.

Top 10 companies by turnover in 2013 in € million were : Renault (4 596), Michelin (2 670), IVECO (1 600), the Valladolid-based supermarket chain Grupo El Árbol (849), cheese processing Queserías Entrepinares (204), sugar processing Acor (201), service group Grupo Norte (174), automobile auxiliary company Faurecia-Asientos de Castilla y León (143), Sada (129) and Hipereco (108).[19]

Transportation

Public transport

Urban transit system was based on the Valladolid tram network from 1881 to 1933. A public urban bus system started in 1928, managed by different private tenders until 1982, when the service was taken over by the municipality. Today the public company AUVASA operates the network, with 22 regular lines and 5 late night lines.

High-speed rail

Valladolid-Campo Grande railway station is integrated into the Spanish high-speed network AVE. The Madrid–Valladolid high-speed rail line was inaugurated on 22 December 2007. The line links both cities, crossing the Sierra de Guadarrama through a tunnel, the fourth longest train tunnel in Europe. Valladolid will become the hub for all AVE lines connecting the north and north-west of Spain with the rest of the country. Trainsets used on this line include S-114 (max speed 250 km/h (155 mph)), S-130 (Patito, max speed 250 km/h (155 mph)) and the S102 (Pato, max speed 320 km/h or 199 mph). This line connects the city with Madrid, which can be reached in 56 minutes.

Roads

Several highways connect the city to the rest of the country.

Airport

The airport serving the city is not located within the municipal limits, but in Villanubla. The airport has connections to Barcelona, Málaga, and the Canary Islands.

Local cuisine

Although an inland province, fish is commonly consumed, some brought from the Cantabrian Sea. Fish like red bream and hake are a major part of Valladolid's cuisine.

The main speciality of Valladolid is, however, lechazo (suckling baby lamb). The lechazo is slowly roasted in a wood oven and served with salad.

Valladolid also offers a great assortment of wild mushrooms. Asparagus, endive and beans can also be found. Some legumes, like white beans and lentils are particularly good. Pine nuts are also produced in great quantities.

Sheep cheese from Villalón de Campos, the famous pata de mulo (mule's foot) is usually unripened (fresh), but if it is cured the ripening process brings out such flavour that it can compete with the best sheep cheeses in Spain.

Valladolid has a bread to go with every dish, like the delicious cuadros from Medina del Campo, the muffins, the pork-scratching bread and the lechuguinos, with a pattern of concentric circles that resemble a head of lettuce.

The pastries and baked goods from the province of Valladolid are well-known, specially St. Mary's ring-shaped pastries, St. Claire's sponge cakes, pine nut balls and cream fritters.

Valladolid is also a producer of wines. The ones that fall under the Designation of Origin Cigales are very good. White wines from Rueda and red wines from Ribera del Duero are known for their quality.

Feasts and festivals

Easter

Holy Week ("Semana Santa" in Spanish) holds one of the best known Catholic traditions in Valladolid. The Good Friday processions are considered an exquisite and rich display of Castilian religious sculpture. On this day, in the morning, members of the brotherhoods on horseback make a poetic proclamation throughout the city. The "Sermon of the Seven Words" is spoken in Plaza Mayor Square. In the afternoon, thousands of people take part in the Passion Procession, comprising 31 pasos (religious statues), most of which date from the 16th and 17th centuries. The last statue in the procession is the Virgen de las Angustias, and her return to the church is one of the most emotional moments of the celebrations, with the Salve Popular sung in her honour.

Easter is one of the most spectacular and emotional fiestas in Valladolid. Religious devotion, art, colour and music combine in acts to commemorate the resurrection of Jesus Christ: the processions. Members of the different Easter brotherhoods, dressed in their characteristic robes, parade through the streets carrying religious statues (pasos) to the sound of drums and music.

Seminci

The city is also host to one of the foremost (and oldest) international film festivals, the Semana Internacional de Cine de Valladolid (Seminci), founded in 1956. Valladolid, through various loopholes in state censorship, was able to present films that would otherwise have been impossible to see in Spain. An award or an enthusiastic reception from the audience and the critics meant, on numerous occasions, that the official state bodies gave the go-ahead to certain films which Francisco Franco's regime considered out of line with their ideology.

Much the same occurred with distribution on the arts circuit at the end of the 60s: a film could be placed more easily if it had previously done well at Valladolid. Even after the death of Franco in 1975, Valladolid continued to be the "testing ground" for films which had been banned. For example, the premiere in Spain of Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange at the 1975 festival is still recalled as a landmark.

As one of Europe's oldest festivals, Valladolid has always been characterized by its willingness to take risks and to innovate in its programming. It has also been keen to critically examine each new school or movement as it has arisen, whether it be German, Polish, Chinese, Canadian or otherwise. With a genuine concern for the art of cinema, for film-making and film-makers rather than the more obvious commercial or glamorous aspects of the industry, the festival has built up an identity of its own – equally attractive to enthusiasts, professionals and the media.

Sports

Valladolid's main association football club is Real Valladolid, nicknamed Pucela, who play in the country's first league, La Liga. Players who went on to play for the Spain national football team include Fernando Hierro, José Luis Caminero and Rubén Baraja. Real's stadium, the Estadio Nuevo José Zorrilla, was built as a venue for the 1982 FIFA World Cup[20] and in preparation staged the 1982 Copa del Rey Final.

CBC Valladolid is the city's new basketball team since the dissolution of CB Valladolid in 2015. Arvydas Sabonis and Oscar Schmidt played for the latter team. Currently playing in the Liga LEB Oro, the CBC Valladolid matches are held at the Polideportivo Pisuerga.

In handball Valladolid is represented by BM Valladolid of the Liga ASOBAL. They have won 2 King's Cup, 1 ASOBAL Cup and 1 EHF Cup. They play their games at the Polideportivo Huerta del Rey.

Rugby union is a very popular sport in Valladolid. CR El Salvador, current champions of Spain's División de Honor de Rugby compete in the European Challenge Cup. They play their matches at Estadio Pepe Rojo. VRAC, current champions of the King's Cup, also plays in the same stadium.

The Valladolid bullring, opened on 29 September 1890, has a capacity of 11,000.

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Valladolid is twinned with:[21]

Notable people

- Sancho the Brave (1258-1295), King of Castile

- Henry IV of Castile (1425-1474), King of Castile and León and brother of Isabella I of Castile

- Juan de Torquemada (1388-1468), Bishop and Cardinal

- Philip II of Spain (1527–1598), King of Spain and Portugal and jure uxoris King of England and Ireland

- Philip IV of Spain (1605–1665), King of Spain and Portugal

- Anne of Austria (1601–1666), Queen of France

- José Zorrilla (1817-1893), writer

- Miguel Delibes (1920-2010), writer

- José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (born 1960), Spanish Prime Minister

- Miriam Blasco (born 1963), judoka

- Francis Ferdinand de Capillas (1607-1648), protomartyr saint of China

- Aodh Ruadh Ó Domhnaill, Irish Gaelic chieftain, was buried here.

See also

Notes

- Named Valladolid before the Independence of Mexico.[22]

References

- Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- "Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Padrón 2013". Archived from the original on 21 March 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2014. Population figures from 1 January 2013.

- Marín, Manuela et al., eds. 1998. The Formation of Al-Andalus: History and Society. Ashgate. ISBN 0-86078-708-7

- Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, v. 23 The Zenith of the Marwanid House, transl. Martin Hinds, Suny, Albany, 1990

- Cabarga, Gloria (17 November 2019). "¿Por qué no nieva en Valladolid?". Tribuna de Salamanca.

- "Valores climatológicos normales. Valladolid" (in Spanish). Agencia Estatal de Meteorología. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- "Valores extremos. Valladolid Aeropuerto" (in Spanish). Agencia Estatal de Meteorología. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- Roger Crowley. Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire. NY: Random House, 2015, p. 161

- Caballero Romero 2015, p. 81.

- Moreno 2018, pp. 181–197.

- Gutiérrez Alonso 1986, p. 11.

- Vega García-Luengos 1997, p. 207.

- "El Duque de Lerma, precursor de la corrupción Inmobiliaria en España". Madridiario. 26 March 2019.

- "¿Cómo dio el 'pelotazo' el Duque de Lerma?". Xlsemanal. 9 April 2018.

- "Accueil Archived 17 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine"/"Inicio Archived 1 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine." Lycée Français de Castilla y León. Retrieved on 13 February 2015. "Avenida de Prado Boyal, n° 28 47140 – Laguna de Duero Valladolid (ESPAÑA)"

- "Home Archived 12 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine"/"Inicio ."

- ÍÑIGO SALINAS (27 August 2008). "De la Riva confía en que las obras del Lope de Vega salgan adelante". El Norte de Castille (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- Data from Informe de Datos Económicos y Sociales de los Municipios de España Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine, written by Caja España

- Castilla y León Económica, no. 211, February 2013

- World Cup 1982 finals. Rsssf.com. Retrieved on 2013-09-05.

- "La plaza de las Ciudades Hermanas de Valladolid". info.valladolid.es (in Spanish). Valladolid. 25 November 2019. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- "Valladolid contempla el hermanamiento con el estado mexicano de Guanajuato ante la petición de cuatro de sus ciudades". 20minutos.es. 28 November 2019.

- "Валядолид, Испания". lovech.bg (in Bulgarian). Lovech. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

Bibliography

- Caballero Romero, Sara (2015). "Epigrafía en el Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales de Madrid: el sepulcro de Doña Juana de Austria" (PDF). Ab Initio. 6 (3): 73–92. ISSN 2172-671X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gutiérrez Alonso, Adriano (1986). "Un espectro poco conocido de la crisis del siglo XVII: el endeudamiento municipal: El ejemplo de la ciudad de Valladolid" (PDF). Investigaciones Históricas: Época Moderna y Contemporánea (6): 7–38. ISSN 0210-9425.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moreno, Doris (2018). "El protestantismo castellano revisitado: geografía y recepción". In Boeglin, Michel; Fernández Terricabras, Ignasi; Kahn, David (eds.). Reforma y disidencia religiosa: la recepción de las doctrinas reformadas en la península ibérica en el siglo XVI. Madrid: Casa de Velázquez.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vega García-Luengos, Germán (1997). "La actividad teatral de la Corte vallisoletana de Felipe III, (1601-1606)" (PDF). In Sabik, Kazimierz (ed.). Actes du Congrès International: Théâtre, Musique et Arts dans les Cours Européennes de la Renaissance et du Baroque. Varsovie, 23-28 septembre 1996. Warsaw: Éditions de l’Université de Varsovie. pp. 205–225.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Valladolid. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Valladolid (Spain). |