Udi language

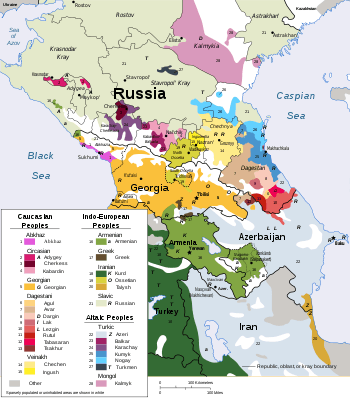

The Udi language, spoken by the Udi people, is a member of the Lezgic branch of the Northeast Caucasian language family.[4] It is believed an earlier form of it was the main language of Caucasian Albania, which stretched from south Dagestan to current day Azerbaijan.[5] The Old Udi language is also called the Caucasian Albanian language[6] and possibly corresponds to the "Gargarian" language identified by medieval Armenian historians.[5] Modern Udi is known simply as Udi.

| Udi | |

|---|---|

| удин муз, udin muz | |

| Native to | Azerbaijan, Russia, Georgia |

| Region | Azerbaijan (Qabala and Oguz), Russia (North Caucasus), Georgia (Kvareli), and Armenia (Tavush) |

| Ethnicity | Udi people |

Native speakers | 3,800 in Azerbaijan (2009 census)[1] 2,800 in Russia and Georgia (no date); unknown number Armenia[2] |

Northeast Caucasian

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | udi |

| Glottolog | udii1243[3] |

The language is spoken by about 4,000 people in the Azerbaijani village of Nij in Qabala rayon, in Oghuz rayon, as well as in parts of the North Caucasus in Russia. It is also spoken by ethnic Udis living in the villages of Debetavan, Bagratashen, Ptghavan, and Haghtanak in Tavush Province of northeastern Armenia and in the village of Zinobiani (former Oktomberi) in the Kvareli Municipality of the Kakheti province of Georgia.

Udi is endangered,[7] classified as "severely endangered" by UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger.[8]

History

The Udi language can most appropriately be broken up into five historical stages:[9]

| Early Udi | around 2000 BC - 300 AD |

| Old Udi | 300 - 900 |

| Middle Udi | 900 - 1800 |

| Early Modern Udi | 1800 - 1920 |

| Modern Udi | 1920 - present |

Soon after the year 700, the Old Udi language had probably ceased to be used for any purpose other than as the liturgical language of the Church of Caucasian Albania.[10]

Syntax

Old Udi was an ergative–absolutive language.[12]

Morphology

Udi is agglutinating with a tendency towards being fusional. Udi affixes are mostly suffixes or infixes, but there are a few prefixes. Old Udi used mostly suffixes.[4] Most affixes are restricted to specific parts of speech. Some affixes behave as clitics. The word order is SOV.[13]

Udi does not have gender, but has declension classes.[14] Old Udi, however, did reflect grammatical gender within anaphoric pronouns.[15]

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lenis | fortis | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||

| Plosive | voiced | b | d | ɡ | |||||

| voiceless | p | t | k | q | |||||

| ejective | pʼ | tʼ | kʼ | qʼ | |||||

| Affricate | voiced | d͡z | d͡ʒ | d͡ʒː | |||||

| voiceless | t͡s | t͡ʃ | t͡ʃː | ||||||

| ejective | t͡sʼ | t͡ʃʼ | t͡ʃːʼ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | ʃː | x | h | ||

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ʒː | ɣ | ||||

| Trill | r | ||||||||

| Approximant | l | j | |||||||

Old Udi, unlike modern Udi, did not have the close-mid front rounded vowel /ø/.[18] Old Udi contained an additional series of palatalized consonants.[19]

Alphabet

The Old Udi language used the Caucasian Albanian alphabet. As evidenced by Old Udi documents discovered at Saint Catherine's Monastery in Egypt dating from the 7th century, the Old Udi language used 50 of the 52 letters identified by Armenian scholars in later centuries as having been used in Udi language texts.[18]

In the 1930s, there was an attempt by Soviet authorities to create an Udi alphabet based on the Latin alphabet but its usage ceased after a short time.

In 1974, a Udi alphabet based on the Cyrillic alphabet was compiled by V. L. Gukasyan. The alphabet in his Udi-Azerbaijani-Russian Dictionary is as follows: А а, Аъ аъ, Аь аь, Б б, В в, Г г, Гъ гъ, Гь гь, Д д, Дж дж, ДжӀ джӀ, Дз дз, Е е, Ж ж, ЖӀ жӀ, З з, И и, Й й, К к, Ҝ ҝ, КӀ кӀ, Къ къ, Л л, М м, Н н, О о, Оь оь, П п, ПӀ пӀ, Р р, С с, Т т, ТӀ тӀ, У у, Уь, Уь, Ф ф, Х х, Хъ хъ, Ц ц, Ц' ц', ЦӀ цӀ, Ч ч, Ч' ч', ЧӀ чӀ, Чъ чъ, Ш ш, ШӀ шӀ, Ы ы. This alphabet was also used in the 1996 collection Nana oččal (Нана очъал).

In the mid-1990s, a new Latin-based Udi alphabet was created in Azerbaijan. A primer and two collections of works by Georgy Kechaari were published using it and it was also used for educational purposes in the village of Nic. The alphabet is as follows:[20]

| A a | B b | C c | Ç ç | D d | E e | Ə ə | F f | G g | Ğ ğ | H h |

| X x | I ı | İ i | Ҝ ҝ | J j | K k | Q q | L l | M m | N n | O o |

| Ö ö | P p | R r | S s | Ş ş | T t | U u | Ü ü | V v | Y y | Z z |

| Ц ц | Цı цı | Eъ eъ | Tı tı | Əъ əъ | Kъ kъ | Pı pı | Xъ xъ | Şı şı | Öъ öъ | Çı çı |

| Çъ çъ | Ć ć | Jı jı | Zı zı | Uъ uъ | Oъ oъ | İъ iъ | Dz dz |

In 2007 in Astrakhan, Vladimir Dabakovym published a collection of Udi folklore with a Latin-based alphabet as follows: A a, Ă ă, Ә ә, B b, C c, Ĉ ĉ, Ç ç, Ç' ç', Č č, Ć ć, D d, E e, Ĕ ĕ, F f, G g, Ğ ğ, H h, I ı, İ i, Ĭ ĭ, J j, Ĵ ĵ, K k, K' k', L l, M m, N n, O o, Ö ö, Ŏ ŏ, P p, P' p', Q q, Q' q', R r, S s, Ś ś, S' s', Ŝ ŝ, Ş ş, T t, T' t', U u, Ü ü, Ŭ ŭ, V v, X x, Y y, Z z, Ź ź.

In 2013 in Russia, an Udi primer, Nanay muz (Нанай муз), was published with a Cyrillic-based alphabet, a modified version of the one used by V. L. Gukasyan in the Udi-Azerbaijani-Russian Dictionary. The alphabet is as follows:[21]

| А а | Аь аь | Аъ аъ | Б б | В в | Г г | Гъ гъ | Гь гь | Д д | Дз дз | Дж дж |

| Джъ джъ | Е е | Ж ж | Жъ жъ | З з | И и | Иъ иъ | Й й | К к | К' к' | Къ къ |

| Л л | М м | Н н | О о | Оь оь | Оъ оъ | П п | П' п' | Р р | С с | Т т |

| Т' т' | У у | Уь уь | Уъ уъ | Ф ф | Х х | Хъ хъ | Ц ц | Ц' ц' | Ч ч | Чъ чъ |

| Ч' ч' | Ч’ъ ч’ъ | Ш ш | Шъ шъ | Ы ы | Э э | Эъ эъ | Ю ю | Я я |

See also

Citations

- "Udi". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-05-28.

- Lewis, M. Paul; Gary F. Simons; Charles D. Fennig, eds. (2013). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (17th ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Udi". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Gippert & Schulze (2007), p. 208.

- Gippert & Schulze (2007), p. 210.

- Gippert & Schulze (2007), p. 201.

- Published in: Encyclopedia of the world’s endangered languages. Edited by Christopher Moseley. London & New York: Routledge, 2007. 211–280.

- UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger

- Schulze (2005).

- Schulze (2005), p. 23.

- Schulze (2005), p. 22.

- Gippert & Schulze (2007), p. 206.

- Schulze, Wolfgang (2002): The Udi language "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-08-05. Retrieved 2012-08-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Harris (1990), p. 7.

- Gippert & Schulze (2007), p. 202.

- Hewitt (2004), p. 57.

- Consonant Systems of the Northeast Caucasian Languages on TITUS DIDACTICA

- Gippert & Schulze (2007), p. 207.

- Gippert & Schulze (2007), pp. 201, 207.

- Y. A. Aydınov and J. A. Keçaari. Tıetıir. Baku, 1996

- Удинский алфавит

References

- Gippert, Jost; Wolfgang, Schulze (2007), "Some Remarks on the Caucasian Albanian Palimsest", Iran and the Caucasus, Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 11 (2): 208, 201–212, doi:10.1163/157338407X265441

- Harris, Alice C. (2006), "History in Support of Synchrony", Berkeley Linguistics Society, 30: 142–159, doi:10.3765/bls.v30i1.942

- Hewitt, George (2004). Introduction to the Study of the Languages of the Caucasus. Munich: Lincom Europa. ISBN 3895867349.

- Schulze, Wolfgang (2005). "Towards a History of Udi" (PDF). International Journal of Diachronic Linguistics: 7, 1–27. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

Further reading

- Harris, Alice C. (2002). Endoclitics and the Origins of Udi Morphosyntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924633-5.

External links

| Udi language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

| For a list of words relating to Udi language, see the Udi language category of words in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Appendix:Cyrillic script

- The Udi Language: A grammatical description with sample text - Wolfgang Schulze 2001

- Udi basic lexicon at the Global Lexicostatistical Database

- The Udis

- Historical map

- A Functional Grammar of Udi, Wolfgang Schulze, 2002

- A Functional Grammar of Udi, Wolfgang Schulze, 2006

- The cognitive dimension of clausal organization in Udi, Wolfgang Schulze, 2000

- The Udi language, Wolfgang Schulze, 2002

- John M. Clifton: The Sociolinguistic Situation of the Udi in Azerbaijan. SIL International, 2005. (PDF-Datei; 206 kB)