Abaza language

The Abaza language (абаза бызшва, abaza byzšwa; Adyghe: абазэбзэ) is a Northwest Caucasian language spoken by Abazins in Russia and many of the exiled communities in Turkey. In fact the language has gone through several different orthographies based primarily on Arabic, Roman, and Cyrillic letters. Its consonant to vowel ratio is remarkably high; making it quite similar to many other languages from the same parent chain. The language evolved during its popularity in the mid to late 1800s and eventually started to die out.[3]

| Abaza | |

|---|---|

| абаза бызшва, abaza byzšwa | |

| Native to | Russia, Turkey |

| Region | Karachay-Cherkessia |

| Ethnicity | Abazins |

Native speakers | 49,800 (2010-2014)[1] |

Northwest Caucasian

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | abq |

| Glottolog | abaz1241[2] |

Abaza is spoken by approximately 35,000 people in Russia, where it is written in a Cyrillic alphabet, as well as another 10,000 in Turkey, where the Latin script is used. It consists of two dialects, the Ashkherewa dialect and the T'ap'anta dialect, which is the literary standard. The language also consists of five sub dialects known as Psyzh-Krasnovostok, Abazakt, Apsua, Kubin-Elburgan and Kuvin.[4]

Abaza, like its relatives in the family of Northwest Caucasian languages, is a highly agglutinative language. For example, the verb in the English sentence "He couldn't make them give it back to her" contains four arguments (a term used in valency grammar): he, them, it, to her. Abaza marks arguments morphologically, and incorporates all four arguments as pronominal prefixes on the verb.[5] The Abaza language contains two dialects in accordance to the Tapanta and Shkaraua familial districts. The subdialects include Abazakt, Apsua, Kubin-Elburgan, Kuvin and Psyzh-Krasnovostok.[6]

It has a large consonantal inventory (63 phonemes) coupled with a minimal vowel inventory (two vowels). It is very closely related to Abkhaz,[7] but it preserves a few phonemes which Abkhaz lacks, such as a voiced pharyngeal fricative. Work on Abaza has been carried out by W. S. Allen, Brian O'Herin, and John Colarusso.

History

The Abaza language has slowly died out. Different forms of cultural annihilation contributed to its fall, in areas of Russia, and over time its overall endangerment. The language can be broken into 5 different dialects and has several unique grammatical approaches to languages. The Abaza Language was at its peak usage in the mid to late 1800s.

Abaza speakers along the Greater and Lesser Laba, Urup, and Greater and Lesser Zelenchuk rivers are from a wave of migrants in the 17th to 18th centuries who represent the Abaza speakers of today. The end of the Great Caucasian War in 1864 provided Russia with power and control of the local regions and contributed to the decrease in the popularity of pre-existing local languages prior to the war.

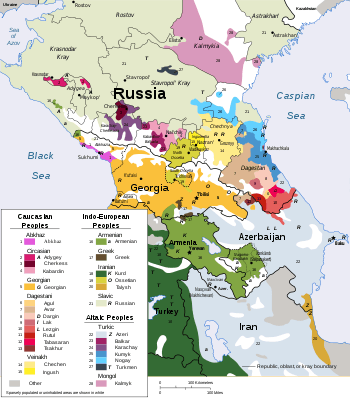

Geographic distribution

The Abaza language is spoken in Russia and Turkey. Although it is endangered, it is still spoken in several regions across Russia. These include Kara-Pago, Kubina, Psikh, El'burgan, Inzhich-Chukun, Koi-dan, Abaza-Khabl', Malo-Abazinka, Tapanta, Krasnovostochni, Novokuvinski, Starokuvinski, Abazakt and Ap-sua.[8]

Phonology

| Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| central | lateral | plain | pal. | lab. | plain | pal. | lab. | plain | pal. | lab. | plain | lab. | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||||||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | kʲ | kʷ | q | qʷ | ʔ | |||||||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ɡʲ | ɡʷ | |||||||||||

| ejective | pʼ | tʼ | kʼ | kʲʼ | kʷʼ | qʼ | qʲʼ | qʷʼ | ||||||||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡s | t̠͡ʃ | ȶ͡ɕ | t̠͡ʃʷ | |||||||||||

| voiced | d͡z | d̠͡ʒ | ȡ͡ʑ | d̠͡ʒʷ | ||||||||||||

| ejective | t͡sʼ | t̠͡ʃʼ | ȶ͡ɕʼ | t̠͡ʃʷʼ | ||||||||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ɬ | ʃ | ɕ | ʃʷ | x | xʲ | xʷ | ħ | ħʷ | ||||

| ejective | fʼ | ɬʼ | ||||||||||||||

| voiced | v | z | ɮ | ʒ | ʑ | ʒʷ | ɣ | ɣʲ | ɣʷ | ʁ | ʁʲ | ʁʷ | ʕ | ʕʷ | ||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||||||||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||||||||

The vowels /o, a, u/ may have a /j/ in front of it. The vowels /e/ and /o/ and /i/ and /u/ are allophones of /a/ and /ə/ before palatalized and labialized consonants respectively. The vowels [e], [o], [i], and [u] can also occurs as variants of the sequences /aj/, /aw/, /əj/ and /əw/.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | (i) | (u) | |

| Mid | (e) | ə | (o) |

| Open | a |

Orthography

Since 1938, Abaza has been written with the version of the Cyrillic alphabet shown below.[11][12]

| А а [a] |

Б б /b/ |

В в /v/ |

Г г /ɡ/ |

Гв гв /ɡʷ/ |

Гъ гъ /ʁ/ |

Гъв гъв /ʁʷ/ |

Гъь гъь /ʁʲ/ |

| Гь гь /ɡʲ/ |

ГӀ гӀ /ʕ/ |

ГӀв гӀв /ʕʷ/ |

Д д /d/ |

Дж дж /d͡ʒ/ |

Джв джв /d͡ʒʷ/ |

Джь джь /d͡ʑ/ |

Дз дз /d͡z/ |

| Е е [e] |

Ё ё [jo] |

Ж ж /ʒ/ |

Жв жв /ʒʷ/ |

Жь жь /ʑ/ |

З з /z/ |

И и [i] |

Й й /j/ |

| К к /k/ |

Кв кв /kʷ/ |

Къ къ /qʼ/ |

Къв къв /qʷʼ/ |

Къь къь /qʲʼ/ |

Кь кь /kʲ/ |

КӀ кӀ /kʼ/ |

КӀв кӀв /kʷʼ/ |

| КӀь кӀь /kʲʼ/ |

Л л /l/ |

Ль ль /ɮ/ |

ЛӀ лӀ /ɬʼ/ |

М м /m/ |

Н н /n/ |

О о [o] |

П п /p/ |

| ПӀ пӀ /pʼ/ |

Р р /r/ |

С с /s/ |

Т т /t/ |

Тл тл /ɬ/ |

Тш тш /t͡ʃ/ |

ТӀ тӀ /tʼ/ |

У у /w/, [u] |

| Ф ф /f/ |

ФӀ фӀ /fʼ/ |

Х х /χ/ |

Хв хв /χʷ/ |

Хъ хъ /q/ |

Хъв хъв /qʷ/ |

Хь хь /χʲ/ |

ХӀ хӀ /ħ/ |

| ХӀв хӀв /ħʷ/ |

Ц ц /t͡s/ |

ЦӀ цӀ /t͡sʼ/ |

Ч ч /t͡ɕ/ |

Чв чв /t͡ʃʷ/ |

ЧӀ чӀ /t͡ɕʼ/ |

ЧӀв чӀв /t͡ʃʷʼ/ |

Ш ш /ʃ/ |

| Шв шв /ʃʷ/ |

ШӀ шӀ /t͡ʃʼ/ |

Щ щ /ɕ/ |

Ъ ъ /ʔ/ |

Ы ы [ə] |

Э э [e] |

Ю ю [ju] |

Я я [ja] |

Grammar

References

- Abaza at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Abaza". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Allen, W. S. (1956). "The Structure and System in the Abaza Verbal Complex". Abaza Language Structure. 55: 127–176. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968X.1956.tb00566.x.

- "The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire". www.eki.ee. Retrieved 2017-02-10.

- Dixon, R.M.W. (2000). "A Typology of Causatives: Form, Syntax, and Meaning". In Dixon, R.M.W. & Aikhenvald, Alexendra Y. Changing Valency: Case Studies in Transitivity. Cambridge University Press. p 57

- "Did you know Abaza is vulnerable?". Endangered Languages. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Abkhaz". Encyclopædia Britannica. I: A-ak Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. pp. 33. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- "Abaza in Russia".

- Starostin, Sergei A.; Nikolayev, Sergei L. (1994). A North Caucasian Etymological Dictionary: Preface, pp. 194-196

- Consonant Systems of the North-West Caucasian Languages (TITUS DIDACTICA)

- Abaza (Place Names Database, Institute of the Estonian Language)

- Abaza alphabet, pronunciation and language (Omniglot)

Further reading

- Генко А. Н. Абазинский язык. Грамматический очерк наречия Тапанта. Москва-Лениград: АН СССР, 1955. (in Russian)

- Ломтатидзе К. В. Тапантский диалект абхазского языка (с текстами). Тбилиси: Издательство Академии Наук Грузинской ССР, 1944. (in Russian)

- Ломтатидзе К. В. Ашхарский диалект и его место среди других абхазско-абазинских диалектов. С текстами. Тбилиси: Издательство Академии Наук Грузинской ССР, 1954. (in Russian)

- Мальбахова-Табулова Н. Т. Грамматика абазинского языка. Фонетика и морфология. Черкесск, 1976. (in Russian)

- Чирикба В. А. Абазинский язык. В: Языки Российской Федерации и Соседних Государств. Энциклопедия. В трех томах. Т. 1. A-И. Москва: Наука, 1998, с. 1-8. (in Russian)

- Allen, W.S. Structure and system in the Abaza verbal complex. In: Transactions of the Philological Society (Hertford), Oxford, 1956, p. 127-176.

- Bouda K. Das Abasinische, eine unbekannte abchasische Mundart. In: ZDMG, BD. 94, H. 2 (Neue Folge, Bd. 19), Berlin-Leipzig, 1940, S. 234—250. (in German)

- O’Herin, B. Case and agreement in Abaza. Summer Institute of Linguistics, September 2002.

External links

| Abaza language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

- The first in the world Abaza–Russian and Russian–Abaza online dictionaries

- Abaza basic lexicon at the Global Lexicostatistical Database

- Recordings in Abaza language

- World Atlas of Language Structures information on Abaza

- Speak Abaza: past, present and future of the Abaza language - World Abaza Congress