Thomas Midgley Jr.

Thomas Midgley Jr. (May 18, 1889 – November 2, 1944) was an American mechanical and chemical engineer. He played a major role in developing leaded gasoline (Tetraethyllead) and some of the first chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), better known by its brand name Freon; both products were later banned due to concerns about their impact on human health and the environment. He was granted more than 100 patents over the course of his career.

Dr. Thomas Midgley Jr. | |

|---|---|

Midgley, c. 1930s–1940s | |

| Born | May 18, 1889 |

| Died | November 2, 1944 (aged 55) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Cornell University |

| Known for |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

Early life

Midgley was born in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, to a father who was also an inventor. He grew up in Columbus, Ohio, and graduated from Cornell University in 1911 with a degree in mechanical engineering.[2][3]

Career

Leaded gasoline

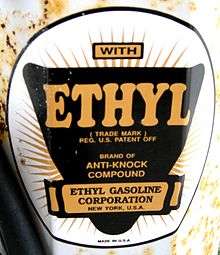

Midgley began working at General Motors in 1916. In December 1921, while working under the direction of Charles Kettering at Dayton Research Laboratories, a subsidiary of General Motors, Midgley discovered that the addition of tetraethyllead to gasoline prevented "knocking" in internal combustion engines.[4] The company named the substance "Ethyl", avoiding all mention of lead in reports and advertising. Oil companies and automobile manufacturers, especially General Motors which owned the patent jointly filed by Kettering and Midgley, promoted the TEL additive as an inexpensive alternative superior to ethanol or ethanol-blended fuels, on which they could make very little profit.[5][6][7] In December 1922, the American Chemical Society awarded Midgley the 1923 Nichols Medal for the "Use of Anti-Knock Compounds in Motor Fuels".[8] This was the first of several major awards he earned during his career.[2]

In 1923, Midgley took a long vacation in Miami, Florida, to cure himself of lead poisoning. He "[found] that my lungs have been affected and that it is necessary to drop all work and get a large supply of fresh air".[9]

In April 1923, General Motors created the General Motors Chemical Company (GMCC) to supervise the production of TEL by the DuPont company. Kettering was elected as president, and Midgley was vice president. However, after two deaths and several cases of lead poisoning at the TEL prototype plant in Dayton, Ohio, the staff at Dayton was said in 1924 to be "depressed to the point of considering giving up the whole tetraethyl lead program".[6] Over the course of the next year, eight more people died at DuPont's plant in Deepwater, New Jersey.[9]

In 1924, unsatisfied with the speed of DuPont's TEL production using the "bromide process", General Motors and the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey (now known as ExxonMobil) created the Ethyl Gasoline Corporation to produce and market TEL. Ethyl Corporation built a new chemical plant using a high-temperature ethyl chloride process at the Bayway Refinery in New Jersey.[9] However, within the first two months of its operation, the new plant was plagued by more cases of lead poisoning, hallucinations, insanity, and five deaths.

On October 30, 1924, Midgley participated in a press conference to demonstrate the apparent safety of TEL, in which he poured TEL over his hands, placed a bottle of the chemical under his nose, and inhaled its vapor for 60 seconds, declaring that he could do this every day without succumbing to any problems.[7][10] However, the State of New Jersey ordered the Bayway plant to be closed a few days later, and Jersey Standard was forbidden to manufacture TEL again without state permission. Midgley would later have to take leave of absence from work after being diagnosed with lead poisoning.[11] He was relieved of his position as vice president of GMCC in April 1925, reportedly due to his inexperience in organizational matters, but he remained an employee of General Motors.[7]

Freon

In the late 1920s, air conditioning and refrigeration systems employed compounds such as ammonia (NH3), chloromethane (CH3Cl), propane, and sulfur dioxide (SO2) as refrigerants. Though effective, these were toxic, flammable or explosive. The Frigidaire division of General Motors, at that time a leading manufacturer of such systems, sought a non-toxic, non-flammable alternative to these refrigerants.[12] Kettering, the vice president of General Motors Research Corporation at that time, assembled a team that included Midgley and Albert Leon Henne to develop such a compound.

The team soon narrowed their focus to alkyl halides (the combination of carbon chains and halogens), which were known to be highly volatile (a requirement for a refrigerant) and also chemically inert. They eventually settled on the concept of incorporating fluorine into a hydrocarbon. They rejected the assumption that such compounds would be toxic, believing that the stability of the carbon–fluorine bond would be sufficient to prevent the release of hydrogen fluoride or other potential breakdown products.[12] The team eventually synthesized dichlorodifluoromethane,[13] the first chlorofluorocarbon (CFC), which they named "Freon".[12][14] This compound is more commonly referred to today as "Freon 12", or "R12".[15]

Freon and other CFCs soon largely replaced other refrigerants, and later appeared in other applications, such as propellants in aerosol spray cans and asthma inhalers. The Society of Chemical Industry awarded Midgley the Perkin Medal in 1937 for this work.

Later life and death

In 1941, the American Chemical Society gave Midgley its highest award, the Priestley Medal.[16] This was followed by the Willard Gibbs Award in 1942. He also held two honorary degrees and was elected to the United States National Academy of Sciences. In 1944, he was elected president and chairman of the American Chemical Society.[2]

In 1940, at the age of 51, Midgley contracted poliomyelitis, which left him severely disabled. He devised an elaborate system of ropes and pulleys to lift himself out of bed. In 1944, he became entangled in the device and died of strangulation.[17][18][19]

Legacy

Midgley's legacy has been scarred by the negative environmental impact of leaded gasoline and Freon.[20] Environmental historian J. R. McNeill opined that Midgley "had more impact on the atmosphere than any other single organism in Earth's history",[21] and Bill Bryson remarked that Midgley possessed "an instinct for the regrettable that was almost uncanny".[22] Use of leaded gasoline, which he invented, released large quantities of lead into the atmosphere all over the world.[20] High atmospheric lead levels have been linked with serious long-term health problems from childhood, including neurological impairment,[23][24][25] and with increased levels of violence and criminality in cities.[26][27][28] Time magazine included both leaded gasoline and CFCs on its list of "The 50 Worst Inventions".[29]

Midgley died three decades before the ozone-depleting and greenhouse gas effects of CFCs in the atmosphere became widely known.[30] In 1987, the Montreal Protocol phased out the use of CFCs like Freon.[31]

References

- "Franklin Laureate Database – Edward Longstreth Medal 1925 Laureates". Franklin Institute. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- Inventors Hall of Fame Profile: Thomas Midgley

- Kettering, Charles F. "Thomas Midgley Jr. 1889–1944" (PDF). Biographical Memoirs. National Academy of Sciences. 24: 359–380.

He decided to try to get a job with me in the organization I had meanwhile developed, the Dayton Engineering Laboratory Company

- Loeb, A.P., "Birth of the Kettering Doctrine: Fordism, Sloanism and Tetraethyl Lead," Business and Economic History, Vol. 24, No. 2, Fall 1995.

- Jacobson, Mark Z. (2002). Atmospheric pollution : history, science, and regulation. Cambridge University Press. pp. 75–80. ISBN 0521010446.

- Kovarik, William (2005). "Ethyl-leaded gasoline: How a classic occupational disease became an international public health disaster" (PDF). International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health. 11 (4): 384–397. doi:10.1179/oeh.2005.11.4.384. PMID 16350473. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- The Secret History of Lead The Nation, March 20, 2000

- Nichols Medalists

- Kovarik, Bill. "Charles F. Kettering and the 1921 Discovery of Tetraethyl Lead In the Context of Technological Alternatives", presented to the Society of Automotive Engineers Fuels & Lubricants Conference, Baltimore, Maryland., 1994; revised in 1999.

- Markowitz, Gerald and Rosner, David. Deceit and Denial: The Deadly Politics of Industrial Pollution. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2002

- The Poisoner's Handbook American Experience at 51:48 January 2014

- Sneader W (2005). "Chapter 8: Systematic medicine". Drug discovery: a history. Chichester, England: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 74–87. ISBN 978-0-471-89980-8. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- Midgley, Thomas; Henne, Albert L. (1930). "Organic Fluorides as Refrigerants1". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 22 (5): 542. doi:10.1021/ie50245a031.

- Thompson, R. J. (1932). "Freon, a Refrigerant". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 24 (6): 620–623. doi:10.1021/ie50270a008.

- Garrett, Alfred B. (1962). "Freon: Thomas Midgley and Albert L. Henne". Journal of Chemical Education. 39 (7): 361. Bibcode:1962JChEd..39..361G. doi:10.1021/ed039p361.

- The Priestley Medalists, 1923-2008 – American Chemical Society

- Bryson, Bill (2004) [First published 2003]. A Short History of Nearly Everything (Black Swan paperback ed.). Transworld Publishers. p. 196. ISBN 0-552-99704-8.

- Alan Bellows (December 8, 2007). "The Ethyl-Poisoned Earth".

- Milestones, Nov. 13, 1944 Time, November 13, 1944.

- Laurence Knight (October 12, 2014). "The fatal attraction of lead". BBC News. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- McNeill, J.R. Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth-Century World (2001) New York: Norton, xxvi, 421 pp. (as reviewed in the "Journal of Political Ecology". Archived from the original on March 28, 2004. Retrieved October 10, 2009.)

- Bryson, Bill (2004) [First published 2003]. A Short History of Nearly Everything (Black Swan paperback ed.). Transworld Publishers. p. 195. ISBN 0-552-99704-8.

- "ToxFAQs: CABS/Chemical Agent Briefing Sheet: Lead" (PDF). Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry/Division of Toxicology and Environmental Medicine. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 9, 2009.

- Golub, Mari S., ed. (2005). "Summary". Metals, fertility, and reproductive toxicity. Boca Raton, Florida: Taylor and Francis. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-415-70040-5.

- Hu, Howard (1991). "Knowledge of diagnosis and reproductive history among survivors of childhood plumbism". American Journal of Public Health. 81 (8): 1070–1072. doi:10.2105/AJPH.81.8.1070. PMC 1405695. PMID 1854006.

- "Aggressiveness and delinquency in boys is linked to lead in bones". The New York Times. 1996.

- "Criminal Element". The New York Times. 2007.

- "America's Real Criminal Element: Lead". Mother Jones. 2013.

- Gentilviso, Chris (May 27, 2010). "The 50 Worst Inventions: Leaded Gasoline". Time. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- Laurence Knight (June 6, 2015). "How 1970s deodorant is still doing harm". BBC News. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- Climate change: 'Monumental' deal to cut HFCs, fastest growing greenhouse gases

External links

- Midgley, T. (1942). "A Critical Examination of Some Concepts in Rubber Chemistry". Science. 96 (2485): 143–6. Bibcode:1942Sci....96..143M. doi:10.1126/science.96.2485.143. PMID 17833986.

- Biographical Memoir by Charles F. Kettering at the Wayback Machine (archived October 15, 2012)

- Giunta, Carmen J. (2006). "Thomas Midgley Jr. and the Invention of Chlorofluorocarbon Refrigerants" (PDF). Bull. Hist. Chem. 31 (2): 66–74.