The Metamorphosis

The Metamorphosis (German: Die Verwandlung) is a novella written by Franz Kafka which was first published in 1915. One of Kafka's best-known works, The Metamorphosis tells the story of salesman Gregor Samsa who wakes one morning to find himself inexplicably transformed into a huge insect (German ungeheures Ungeziefer, literally "monstrous vermin"), subsequently struggling to adjust to this new condition. The novella has been widely discussed among literary critics, with differing interpretations being offered.

First edition cover | |

| Author | Franz Kafka |

|---|---|

| Original title | Die Verwandlung |

| Country | Austria–Hungary, today Czech Republic |

| Language | German |

| Publisher | Kurt Wolff Verlag, Leipzig |

Publication date | 1915 |

| Translation | The Metamorphosis at Wikisource |

Plot

Gregor Samsa wakes up one morning to find himself transformed into a "monstrous vermin". He initially considers the transformation to be temporary and slowly ponders the consequences of this metamorphosis. Unable to get up and leave the bed, Gregor reflects on his job as a traveling salesman and cloth merchant, which he characterizes as being full of "temporary and constantly changing human relationships, which never come from the heart". He sees his employer as a despot and would quickly quit his job were he not his family's sole breadwinner and working off his bankrupt father's debts. While trying to move, Gregor finds that his office manager, the chief clerk, has shown up to check on him, indignant about Gregor's unexcused absence. Gregor attempts to communicate with both the manager and his family, but all they can hear from behind the door is incomprehensible vocalizations. Gregor laboriously drags himself across the floor and opens the door. The manager, upon seeing the transformed Gregor, flees the apartment. Gregor's family is horrified, and his father drives him back into his room under the threat of violence.

With Gregor's unexpected incapacitation, the family is deprived of their financial stability. Although Gregor's sister Grete now shies away from the sight of him, she takes to supplying him with food, which they find he can only eat rotten. Gregor begins to accept his new identity and begins crawling on the floor, walls and ceiling. Discovering Gregor's new pastime, Grete decides to remove some of the furniture to give Gregor more space. She and her mother begin taking furniture away, but Gregor finds their actions deeply distressing. He desperately tries to save a particularly-loved portrait on the wall of a woman clad in fur. His mother loses consciousness at the sight of Gregor clinging to the image to protect it. As Grete rushes to assist her mother, Gregor follows her and is hurt by a medicine bottle falling on his face. His father returns home from work and angrily hurls apples at Gregor. One of them is lodged into a sensitive spot in his back and severely wounds him.

Gregor suffers from his injuries for several weeks and takes very little food. He is increasingly neglected by his family and his room becomes used for storage. To secure their livelihood, the family takes three tenants into their apartment. The cleaning lady alleviates Gregor's isolation by leaving his door open for him on the evenings that the tenants eat out. One day, his door is left open despite the presence of the tenants. Gregor, attracted by Grete's violin-playing in the living room, crawls out of his room and is spotted by the unsuspecting tenants, who complain about the apartment's unhygienic conditions and cancel their tenancy. Grete, who has by now become tired of taking care of Gregor and is realizing the burden his existence puts on each one in the family, tells her parents they must get rid of "it", or they will all be ruined. Gregor, understanding that he is no longer wanted, dies of starvation before the next sunrise. The relieved and optimistic family take a tram ride out to the countryside, and decide to move to a smaller apartment to further save money. During this short trip, Mr. and Mrs. Samsa realize that, in spite of going through hardships which have brought an amount of paleness to her face, Grete appears to have grown up into a pretty and well-figured lady, which leads her parents to think about finding her a husband.

Characters

Gregor Samsa

Gregor is the main character of the story. He works as a traveling salesman in order to provide money for his sister and parents. He wakes up one morning finding himself transformed into an insect. After the metamorphosis, Gregor becomes unable to work and is confined to his room for most of the remainder of the story. This prompts his family to begin working once again. Gregor is depicted as isolated from society and often misunderstands the true intentions of others and is often misunderstood, in turn.

The name "Gregor Samsa" appears to derive partly from literary works Kafka had read. A character in The Story of Young Renate Fuchs, by German-Jewish novelist Jakob Wassermann (1873–1934), is named Gregor Samassa.[1] The Viennese author Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, whose sexual imagination gave rise to the idea of masochism, is also an influence. Sacher-Masoch wrote Venus in Furs (1870), a novel whose hero assumes the name Gregor at one point. A "Venus in furs" literally recurs in The Metamorphosis in the picture that Gregor Samsa has hung on his bedroom wall.[2]

Grete Samsa

Grete is Gregor's younger sister, who becomes his caretaker after his metamorphosis. Initially Grete and Gregor have a close relationship, but this quickly fades. While Grete initially volunteers to feed him and clean his room, she grows increasingly impatient with the burden and begins to leave his room in disarray out of spite. Her initial decision to take care of Gregor may have come from a desire to contribute and be useful to the family, since she becomes angry and upset when the mother cleans his room, and it is made clear that Grete is disgusted by Gregor; she could not enter Gregor's room without opening the window first because of the nausea he caused her, and leaves without doing anything if Gregor is in plain sight. She plays the violin and dreams of going to the conservatory, a dream Gregor had intended to make happen; Gregor had planned on making the announcement on Christmas Day. To help provide an income for the family after Gregor's transformation, she starts working as a salesgirl. Grete is also the first to suggest getting rid of Gregor, which causes Gregor to plan his own death. At the end of the story, Grete's parents realize that she has become beautiful and full-figured and decide to consider finding her a husband.[3]

Mr. Samsa

Mr. Samsa is Gregor's father. After the metamorphosis, he is forced to return to work in order to support the family financially. His attitude towards his son is harsh; he regards the transformed Gregor with disgust and possibly even fear, and he attacks him on several occasions.[4]

Mrs. Samsa

Mrs. Samsa is Grete and Gregor's mother. She is initially shocked at Gregor's transformation; however, she wants to enter his room. This proves too much for her, thus giving rise to a conflict between her maternal impulse and sympathy, and her fear and revulsion at Gregor's new form.[5]

The Charwoman

The Charwoman is an old lady who is employed by the Samsa family to help take care of their household duties. Apart from Grete and her father, she is the only person who is in close contact with Gregor. She is the one who notices that Gregor has died and disposes of his body.

Interpretation

Like most Kafka works, The Metamorphosis tends to entail the use of a religious (Max Brod) or psychological interpretation by most of its interpreters. It has been particularly common to read the story as an expression of Kafka's father complex, as was first done by Charles Neider in his The Frozen Sea: A Study of Franz Kafka (1948). Besides the psychological approach, interpretations focusing on sociological aspects which see the Samsa family as a portrayal of general social circumstances, have gained a large following as well.[6]

Vladimir Nabokov rejected such interpretations, noting that they do not live up to Kafka's art. He instead chose an interpretation guided by the artistic detail but categorically excluded any and all attempts at deciphering a symbolic or allegoric level of meaning. Arguing against the popular father complex theory, he observed that it is the sister, more so than the father, who should be considered the cruelest person in the story, as she is the one backstabbing Gregor. In Nabokov's view, the central narrative theme is the artist's struggle for existence in a society replete with philistines that destroys him step by step. Commenting on Kafka's style, he writes: "The transparency of his style underlines the dark richness of his fantasy world. Contrast and uniformity, style and the depicted, portrayal and fable are seamlessly intertwined".[7]

In 1989, Nina Pelikan Straus wrote a feminist interpretation of The Metamorphosis, bringing to the forefront the transformation of the main character Gregor's sister, Grete, and foregrounding the family and, particularly, younger sister's transformation in the story. Traditionally, critics of The Metamorphosis have underplayed the fact that the story is not only about Gregor but also his family and especially about Grete's metamorphosis as it is mainly Grete, as woman, daughter and sister, on whom the social and psychoanalytic resonances of the text depend.[8]

In 1999, Gerhard Rieck pointed out that Gregor and his sister Grete form a pair, which is typical for many of Kafka's texts: It is made up of one passive, rather austere person and another active, more libidinal person. The appearance of figures with such almost irreconcilable personalities who form couples in Kafka's works has been evident since he wrote his short story "Description of a Struggle" (e.g. the narrator/young man and his "acquaintance"). They also appear in "The Judgement" (Georg and his friend in Russia), in all three of his novels (e.g. Robinson and Delamarche in Amerika) as well as in his short stories "A Country Doctor" (the country doctor and the groom) and "A Hunger Artist" (the hunger artist and the panther). Rieck views these pairs as parts of one single person (hence the similarity between the names Gregor and Grete), and in the final analysis as the two determining components of the author's personality. Not only in Kafka's life but also in his oeuvre does Rieck see the description of a fight between these two parts.[9]

Reiner Stach argued in 2004 that no elucidating comments were needed to illustrate the story and that it was convincing by itself, self-contained, even absolute. He believes that there is no doubt the story would have been admitted to the canon of world literature even if we had known nothing about its author.[10]

According to Peter-André Alt (2005), the figure of the vermin becomes a drastic expression of Gregor Samsa's deprived existence. Reduced to carrying out his professional responsibilities, anxious to guarantee his advancement and vexed with the fear of making commercial mistakes, he is the creature of a functionalistic professional life.[11]

In 2007, Ralf Sudau took the view that particular attention should be paid to the motifs of self-abnegation and disregard for reality. Gregor's earlier behavior was characterized by self-renunciation and his pride in being able to provide a secure and leisured existence for his family. When he finds himself in a situation where he himself is in need of attention and assistance and in danger of becoming a parasite, he doesn't want to admit this new role to himself and be disappointed by the treatment he receives from his family, which is becoming more and more careless and even hostile over time. According to Sudau, Gregor is self-denyingly hiding his nauseating appearance under the canapé and gradually famishing, thus pretty much complying with the more or less blatant wish of his family. His gradual emaciation and "self-reduction" shows signs of a fatal hunger strike (which on the part of Gregor is unconscious and unsuccessful, on the part of his family not understood or ignored). Sudau also lists the names of selected interpreters of The Metamorphosis (e.g. Beicken, Sokel, Sautermeister and Schwarz).[12] According to them, the narrative is a metaphor for the suffering resulting from leprosy, an escape into the disease or a symptom onset, an image of an existence which is defaced by the career, or a revealing staging which cracks the veneer and superficiality of everyday circumstances and exposes its cruel essence. He further notes that Kafka's representational style is on one hand characterized by an idiosyncratic interpenetration of realism and fantasy, a worldly mind, rationality and clarity of observation, and on the other hand by folly, outlandishness and fallacy. He also points to the grotesque and tragicomical, silent film-like elements.[13]

Fernando Bermejo-Rubio (2012) argued that the story is often viewed unjustly as inconclusive. He derives his interpretative approach from the fact that the descriptions of Gregor and his family environment in The Metamorphosis contradict each other. Diametrically opposed versions exist of Gregor's back, his voice, of whether he is ill or already undergoing the metamorphosis, whether he is dreaming or not, which treatment he deserves, of his moral point of view (false accusations made by Grete) and whether his family is blameless or not. Bermejo-Rubio emphasizes that Kafka ordered in 1915 that there should be no illustration of Gregor. He argues that it is exactly this absence of a visual narrator that is essential for Kafka's project, for he who depicts Gregor would stylize himself as an omniscient narrator. Another reason why Kafka opposed such an illustration is that the reader should not be biased in any way before his reading process was getting under way. That the descriptions are not compatible with each other is indicative of the fact that the opening statement is not to be trusted. If the reader isn't hoodwinked by the first sentence and still thinks of Gregor as a human being, he will view the story as conclusive and realize that Gregor is a victim of his own degeneration.[14]

Volker Drüke (2013) believes that the crucial metamorphosis in the story is that of Grete. She is the character the title is directed at. Gregor's metamorphosis is followed by him languishing and ultimately dying. Grete, by contrast, has matured as a result of the new family circumstances and assumed responsibility. In the end – after the brother's death – the parents also notice that their daughter, "who was getting more animated all the time, had blossomed […] into a beautiful and voluptuous young woman", and want to look for a partner for her. From this standpoint, Grete's transition, her metamorphosis from a girl into a woman, is the subtextual theme of the story.[15]

Translation

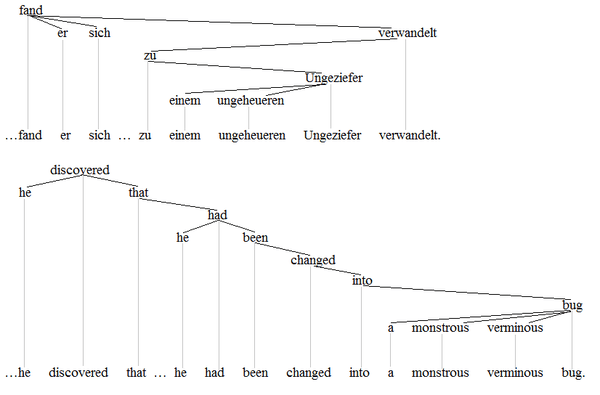

Kafka's sentences often deliver an unexpected effect just before the period – that being the finalizing meaning and focus. This is achieved from the construction of sentences in the original German, where the verbs of subordinate clauses are put at the end. For example, in the opening sentence, it is the final word, verwandelt, that indicates transformation:

Als Gregor Samsa eines Morgens aus unruhigen Träumen erwachte, fand er sich in seinem Bett zu einem ungeheuren Ungeziefer verwandelt.

As Gregor Samsa one morning from uneasy dreams awoke, he found himself in his bed into a gigantic insect-like creature transformed.

These constructions are not directly translatable to English, so it is up to the translator to provide the reader with the effect of the original text.[16]

English translators have often sought to render the word Ungeziefer as "insect", but this is not strictly accurate. In Middle High German, Ungeziefer literally means "unclean animal not suitable for sacrifice"[17] and is sometimes used colloquially to mean "bug" – a very general term, unlike the scientific sounding "insect". Kafka had no intention of labeling Gregor as any specific thing, but instead wanted to convey Gregor's disgust at his transformation. The phrasing used by Joachim Neugroschelis: "Gregor Samsa found himself, in his bed, transformed into a monstrous vermin", [18] whereas David Wyllie says, "transformed in his bed into a horrible vermin".[19]

However, in Kafka's letter to his publisher of 25 October 1915, in which he discusses his concern about the cover illustration for the first edition, he uses the term Insekt, saying: "The insect itself is not to be drawn. It is not even to be seen from a distance."[20]

Ungeziefer has sometimes been translated as "cockroach", "dung beetle", "beetle", and other highly specific terms. The term "dung beetle" or Mistkäfer is, in fact, used by the cleaning lady near the end of the story, but it is not used in the narration: "At first, she also called him to her with words which she presumably thought were friendly, like 'Come here for a bit, old dung beetle!’ or 'Hey, look at the old dung beetle!’" Ungeziefer also denotes a sense of separation between himself and his environment: he is unclean and must therefore be secluded.

Vladimir Nabokov, who was a lepidopterist as well as a writer and literary critic, insisted that Gregor was not a cockroach, but a beetle with wings under his shell, and capable of flight. Nabokov left a sketch annotated, "just over three feet long", on the opening page of his (heavily corrected) English teaching copy. In his accompanying lecture notes, Nabokov discusses the type of insect Gregor has been transformed into, concluding that Gregor "is not, technically, a dung beetle. He is merely a big beetle".[21]

English translations

- 1946: A.L. Lloyd

- 1961: Edwin Muir and Willa Muir

- 1972: Stanley Corngold

- 1981: J.A. Underwood

- 1992: Malcolm Pasley (titled "The Transformation")

- 1993: Joachim Neugroschel

- 1996: Stanley Appelbaum

- 1999: Ian Johnston (public domain)

- 2002: David Wyllie

- 2002: Richard Stokes

- 2007: Michael Hofmann

- 2009: Joyce Crick

- 2009: William Aaltonen

- 2014: Christopher Moncrieff

- 2014: Susan Bernofsky

- 2014: John R. Williams

- 2017: Karen Reppin

- 2006: audio by David Barnes

- 2012: audio by David Richardson

- 2014: audio by Bob Neufeld

- 2014: audio by Edoardo Ballerini

Editions in the original German

- First print: Die Verwandlung. In: Die Weißen Blätter. Eine Monatsschrift. (The White Pages. A Monthly). ed. René Schickele. "Jg. 2" (1915), "H. 10" (October), pp. 1177–1230.

- Sämtliche Erzählungen. paperback, ed. Paul Raabe. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main and Hamburg 1970. ISBN 3-596-21078-X.

- Drucke zu Lebzeiten. ed. Wolf Kittler, Hans-Gerd Koch and Gerhard Neumann, S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1996, pp. 113–200.

- Die Erzählungen. (The stories) ed. Roger Herms, original version S. Fischer Verlag 1997 ISBN 3-596-13270-3

- Die Verwandlung. with a commentary by Heribert Kuhn, Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 978-3-518-18813-2. (Suhrkamp BasisBibliothek, 13: Text und Kommentar)

- Die Verwandlung. Anaconda Verlag, Köln 2005. ISBN 978-3-938484-13-5.

In popular culture

References

- Germany, SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg. "Die Geschichte der jungen Renate Fuchs von Jakob Wassermann - Text im Projekt Gutenberg". gutenberg.spiegel.de (in German). Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- Kafka (1996, 3).

- "The character of Grete Samsa in The Metamorphosis from LitCharts | The creators of SparkNotes". LitCharts. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- "The character of Father in The Metamorphosis from LitCharts | The creators of SparkNotes". LitCharts. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- "The Metamorphosis: Mother Character Analysis". LitCharts.

- Abraham, Ulf. Franz Kafka: Die Verwandlung. Diesterweg, 1993. ISBN 3-425-06172-0.

- Nabokov, Vladimir V. Die Kunst des Lesens: Meisterwerke der europäischen Literatur. Austen – Dickens – Flaubert – Stevenson – Proust – Kafka – Joyce. Fischer Taschenbuch, 1991, pp. 313–52. ISBN 3-596-10495-5.

- Pelikan Straus, Nina. Transforming Franz Kafka's Metamorphosis Signs, 14:3, (Spring, 1989), The University of Chicago Press, pp. 651–67.

- Rieck, Gerhard. Kafka konkret – Das Trauma ein Leben. Wiederholungsmotive im Werk als Grundlage einer psychologischen Deutung. Königshausen & Neumann, 1999, pp. 104–25. ISBN 978-3-8260-1623-3.

- Stach, Reiner. Kafka. Die Jahre der Entscheidungen, p. 221.

- Alt, Peter-André. Franz Kafka: Der Ewige Sohn. Eine Biographie. C.H.Beck, 2008 , p. 336.

- Sudau, Ralf. Franz Kafka: Kurze Prosa / Erzählungen. Klett, 2007, pp. 163–64.

- Sudau, Ralf. Franz Kafka: Kurze Prosa / Erzählungen. Klett, 2007, pp. 158–62.

- Bermejo-Rubio, Fernando: "Truth and Lies about Gregor Samsa. The Logic Underlying the Two Conflicting Versions in Kafka’s Die Verwandlung”. In: Deutsche Vierteljahrsschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte, Volume 86, Issue 3 (2012), pp. 419–79.

- Drüke, Volker. "Neue Pläne Für Grete Samsa". Übergangsgeschichten. Von Kafka, Widmer, Kästner, Gass, Ondaatje, Auster Und Anderen Verwandlungskünstlern, Athena, 2013, pp. 33–43. ISBN 978-3-89896-519-4.

- Kafka, Franz (1996). The Metamorphosis and Other Stories. p. xi. ISBN 1-56619-969-7.

- Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Deutschen. Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag. 1993. p. 1486. ISBN 3423325119.

- Kafka, Franz (22 May 2000). The Metamorphosis, in the Penal Colony and Other Stories: The Great Short Works of Franz Kafka. ISBN 0-684-80070-5.

- Kafka, Franz. "Metamorphosis". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- "Briefe und Tagebücher 1915 (Franz Kafka) — ELibraryAustria".

- Nabokov, Vladimir (1980). Lectures on Literature. New York, New York: Harvest. p. 260.

External links

| German Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kafka Die Verwandlung. |

Online editions

- Die Verwandlung at DigBib.org (text, pdf, HTML) (in German)

- The Metamorphosis, translated 2009 by Ian Johnston of Malaspina University-College, Nanaimo, BC

- The Metamorphosis at The Kafka project, translated by Ian Johnston released to public domain

- The Metamorphosis - Annotated text aligned to Common Core Standards

- The Metamorphosis at Project Gutenberg, translated by David Wyllie

- Lecture on The Metamorphosis by Vladimir Nabokov

Commentary

Related