Taxila

Taxila (from Pāli Brahmi: 𑀢𑀔𑁆𑀔𑀲𑀺𑀮𑀸, Takhkhasilā,[2] Sanskrit: तक्षशिला, IAST: Takṣaśilā, Urdu: تکششیلا meaning "City of Cut Stone" or "Takṣa Rock") in Sanskrit is a significant archaeological site in the modern city of the same name in Punjab, Pakistan. It lies about 32 km (20 mi) north-west of Islamabad and Rawalpindi, just off the famous Grand Trunk Road.

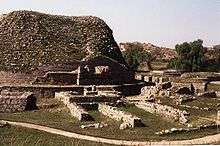

View of the Dharmarajika, an ancient stupa | |

Taxila Shown within Pakistan  Taxila Taxila (Gandhara) | |

| Location | Rawalpindi district, Punjab

|

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 33°44′45″N 72°47′15″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 1000 BCE[1] |

| Abandoned | 5th century |

| Official name | Taxila |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, vi |

| Designated | 1980 (4th session) |

| Reference no. | 139 |

| Region | Southern Asia |

Ancient Taxila was an important city of Ancient India, situated at the pivotal junction of the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia. The origin of Taxila as a city goes back to c. 1000 BCE.[1] Some ruins at Taxila date to the time of the Achaemenid Empire in the 6th century BCE, followed successively by Mauryan Empire, Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian, and Kushan Empire periods.

Owing to its strategic location, Taxila has changed hands many times over the centuries, with many empires vying for its control. When the great ancient trade routes connecting these regions ceased to be important, the city sank into insignificance and was finally destroyed by the nomadic Hunas in the 5th century. The renowned archaeologist Sir Alexander Cunningham rediscovered the ruins of Taxila in the mid-19th century. In 1980, Taxila was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[3] In 2006 it was ranked as the top tourist destination in Pakistan by The Guardian newspaper.[4]

By some accounts, the University of Ancient Taxila was considered to be one of the earliest universities in the world.[5][6][7][8][9] Others do not consider it a university in the modern sense, in that the teachers living there may not have had official membership of particular colleges, and there did not seem to have existed purpose-built lecture halls and residential quarters in Taxila,[10][11][12] in contrast to the later Nalanda university in eastern India.[12][13][14]

In a 2010 report, Global Heritage Fund identified Taxila as one of 12 worldwide sites most "On the Verge" of irreparable loss and damage, citing insufficient management, development pressure, looting, and war and conflict as primary threats.[15] However, significant preservation efforts have been carried out since then by the government which have resulted in the site being declared as "well-preserved" by different international publications.[16] Because of the extensive preservation efforts and upkeep, the site is a popular tourist spot, attracting up to one million tourists every year.[16][17]

Etymology

Taxila was known in Pali as Takkasilā,[18] and in Sanskrit as तक्षशिला (Takshashila, IAST: Takṣaśilā; "City of Cut Stone"). The Greeks pared the city's name down to Taxila[19][20] which became the name that the Europeans were familiar with ever since the time of Alexander the Great.[21]

Takshashila can also alternately be translated to "Rock of Taksha" in reference to the Ramayana which states that the city was named in honour of Bharata's son and first ruler, Taksha.[19] According to another derivation, Takshashila is related to Takshaka (Sanskrit for "carpenter") and is an alternate name for the Nāga, a non-Indo-Iranian people of ancient India.[22]

Faxian who had visited the city had given its name's meaning as "Cut off Head". With the help of a Jataka, he had interperted it to be the place where Buddha in his previous birth as Pusa or Chandaprabha cut off his head to feed a hungry lion. This tradition still persists with the area in front of Sirkap (also meaning "cut off head") was known in the 19th century as Babur Khana ("House of Tiger"), which alludes to the place where Buddha offered his head. In addition, a hill range to south of Taxila Valley is called Margala ("cut off throat").[23]

In traditional sources

In Vedic texts such as the Shatapatha Brahmana, it is mentioned that the Vedic philosopher Uddalaka Aruni (c. 7th century BCE) had travelled to the region of Gandhara. In later Buddhist texts, the Jatakas, it is specified that Taxila was the city where Aruni and his son Shvetaketu each had received their education.[24]

One of the earliest mentions of Taxila is in Pāṇini's Aṣṭādhyāyī,[18] a Sanskrit grammar treatise dated to the 5th century BCE.

Much of the Hindu epic, the Mahabharata, is a conversation between Vaishampayana (a pupil of the sage, Vyasa) and King Janamejaya. It is traditionally believed that the story was first recited by Vaishampayana at the behest of Vyasa during the snake sacrifice performed by Janamejaya at Takshashila.[19] The audience also included Ugrashravas, an itinerant bard, who would later recite the story to a group of priests at an ashram in the Naimisha Forest from where the story was further disseminated.[25] The Kuru Kingdom's heir, Parikshit (grandson of Arjuna) is said to have been enthroned at Takshashila.[26]

The Ramayana describes Takshashila as a magnificent city famed for its wealth which was founded by Bharata, the younger brother of Rama. Bharata, who also founded nearby Pushkalavati, installed his two sons, Taksha and Pushkala, as the rulers of the two cities.[27]

In the Buddhist Jatakas, Taxila is described as the capital of the kingdom of Gandhara and a great centre of learning with world-famous teachers.[19] The Takkasila Jataka, more commonly known as the Telapatta Jataka, tells the tale of a prince of Benares who is told that he would become the king of Takkasila if he could reach the city within seven days without falling prey to the yakkhinis who waylaid travellers in the forest.[28][29] According to the Dipavamsa, one of Taxila's early kings was a Kshatriya named Dipankara who was succeeded by twelve sons and grandsons. Kuñjakarṇa, mentioned in the Avadanakalpalata, is another king associated with the city.[27]

In the Jain tradition, it is said that Rishabha, the first of the Tirthankaras, visited Taxila millions of years ago. His footprints were subsequently consecrated by Bahubali who erected a throne and a dharmachakra ("wheel of the law") over them several miles in height and circumference.[27]

History

Early settlement

The region around Taxila was settled by the neolithic era, with some ruins at Taxila dating to 3360 BCE.[30] Ruins dating from the Early Harappan period around 2900 BCE have also been discovered in the Taxila area,[30] though the area was eventually abandoned after the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilisation.

The first major settlement at Taxila, in Hathial mound, was established around 1000 BCE.[31][32][33] By 900 BCE, the city was already involved in regional commerce, as discovered pottery shards reveal trading ties between the city and Puṣkalāvatī.[34]

Later on, Taxila was inhabited at Bhir Mound, dated to sometime around the period 800-525 BCE with these early layers bearing "grooved" Red Burnished Ware,[35]

Achaemenid

Archaeological excavations show that the city may have grown significantly during the rule of the Persian Achaemenid Empire in the 6th century BCE. In 516 BCE, Darius I embarked on a campaign to conquer Central Asia, Ariana and Bactria, before marching onto what is now Afghanistan and northern Pakistan. Emperor Darius spent the winter of 516-515 BCE in the Gandhara region surrounding Taxila, and prepared to conquer the Indus Valley, which he did in 515 BCE,[36] after which he appointed Scylax of Caryanda to explore the Indian Ocean from the mouth of the Indus to the Suez. Darius then returned to Persia via the Bolan Pass. The region continued under Achaemenid suzerainty under the reign of Xerxes I, and continued under Achaemenid rule for over a century.[37]

Taxila was sometimes ruled as part of the Gandhara kingdom (whose capital was Pushkalavati), particularly after the Achaemenid period, but Taxila sometimes formed its own independent district or city-state.[38][39]

Hellenistic

During his invasion of the Indus Valley, Alexander the Great was able to gain control of Taxila (Ancient Greek: Τάξιλα)[40] in 326 BCE without a battle, as the city was surrendered by its ruler, king Omphis (Āmbhi).[37] Greek historians accompanying Alexander described Taxila as "wealthy, prosperous, and well governed".[37] Arrian writes that Alexander was welcomed by the citizens of the city, and he offered sacrifices and celebrated a gymnastic and equestrian contest there.[41]

Mauryan

By 317 BCE, the Greek satraps left by Alexander were driven out,[42] and Taxila came under the control of Chandragupta Maurya, who turned Taxila into a regional capital. His advisor, Kautilya/Chanakya, was said to have taught at Taxila's university.[43] Under the reign of Ashoka, Chandragupta's grandson, the city was made a great seat of Buddhist learning, though the city was home to a minor rebellion during this time.[44]

Taxila was founded in a strategic location along the ancient "Royal Highway" that connected the Mauryan capital at Pataliputra in Bihar, with ancient Peshawar, Puṣkalāvatī, and onwards towards Central Asia via Kashmir, Bactria, and Kāpiśa.[45] Taxila thus changed hands many times over the centuries, with many empires vying for its control.

Indo-Greek

In the 2nd century BCE, Taxila was annexed by the Indo-Greek kingdom of Bactria. Indo-Greeks built a new capital, Sirkap, on the opposite bank of the river from Taxila.[46] During this new period of Bactrian Greek rule, several dynasties (like Antialcidas) likely ruled from the city as their capital. During lulls in Greek rule, the city managed profitably on its own, to independently control several local trade guilds, who also minted most of the city's autonomous coinage. In about the 1st century BCE or 1st century CE, an Indo-Scythian king named Azilises had three mints, one of which was at Taxila, and struck coins with obverse legends in Greek and Kharoṣṭhī.

The last Greek king of Taxila was overthrown by the Indo-Scythian chief Maues around 90 BCE.[47] Gondophares, founder of the Indo-Parthian Kingdom, conquered Taxila around 20 BCE, and made Taxila his capital.[48] According to early Christian legend, Thomas the Apostle visited Gondophares IV around 46 CE,[49] possibly at Taxila given that city was Gondophares' capital city.

Kushan

Around the year 50 CE, the Greek Neopythagorean philosopher Apollonius of Tyana allegedly visited Taxila, which was described by his biographer, Philostratus, writing some 200 years later, as a fortified city laid out on a symmetrical plan, similar in size to Nineveh. Modern archaeology confirms this description.[50] Inscriptions dating to 76 CE demonstrate that the city had come under Kushan rule by that time, after the city was captured from the Parthians by Kujula Kadphises, founder of the Kushan Empire.[51] The great Kushan ruler Kanishka later founded Sirsukh, the most recent of the ancient settlements at Taxila.

Gupta

In the mid fourth century CE, the Gupta Empire occupied the territories in Eastern Gandhara, establishing a Kumaratya's post at Taxila. The City became well known for its Trade links- including Silk, Sandalwood, Horses, Cotton, Silverware, Pearls, and Spices. It is during this time that the City heavily features in Classical Indian Literature- both as a centre of Culture as well as a militarised border City.[52][53]

Taxila's university remained in existence during the travels of Chinese pilgrim Faxian, who visited Taxila around 400 CE.[54] He wrote that Taxila's name translated as "the Severed Head", and was the site of a story in the life of Buddha "where he gave his head to a man".[55]

Decline

The Kidarites, vassals of the Hephthalite Empire are known to have invaded Taxila in c. 450 CE. Though repelled by the Gupta Emperor Skandagupta, the city would not recover- probably on account of the strong Hunnic presence in the area, breakdown of trade as well as the three-way war between Persia, the Kidarite State, and the Huns in Western Gandhara.

The White Huns swept over Gandhāra and Punjab around 470 CE, causing widespread devastation and destruction of Taxila's famous Buddhist monasteries and stupas, a blow from which the city would never recover. From 500 CE to 540 CE, the city fell under the control of the Hunnic Empire in South Asia and languished.[56]

Xuanzang visited India between 629 to 645 CE. Taxila which was desolate and half-ruined was visited by him in 630 CE, and found most of its sangharamas still ruined and desolate. Only a few monks remained there. He adds that the kingdom had become a dependency of Kashmir with the local leaders fighting amongst themselves for power. He noted that it had some time previously been a subject of Kapisa. By the ninth century, it became a dependency of the Kabul Shahis. The Turki Shahi dynasty of Kabul was replaced by the Hindu Shahi dynasty which was overthrown by Mahmud of Ghazni with the defeat of Trilochanpala.[57][58]

Al-Usaifan's king during the reign of Al-Mu'tasim is said to have converted to Islam by Al-Biladhuri and abandoned his old faith due to the death of his son despite having priests of a temple pray for his recovery. Said to be located between Kashmir, Multan and Kabul, al-Usaifan is identified with kingdom of Taxila by some authors.[59][60]

Centre of learning

By some accounts, Taxila was considered to be one of the earliest (or the earliest) universities in the world.[54][61][62] Others do not consider it a university in the modern sense, in that the teachers living there may not have had official membership of particular colleges, and there did not seem to have existed purpose-built lecture halls and residential quarters in Taxila,[63][64] in contrast to the later Nalanda university in eastern India.[19][13][14]

Taxila became a noted centre of learning (including the religious teachings of Buddhism) at least several centuries BCE, and continued to attract students from around the old world until the destruction of the city in the 5th century. It has been suggested that at its height, Taxila exerted a sort of "intellectual suzerainty" over other centres of learning in India and its primary concern was not with elementary, but higher education.[62] Generally, a student entered Taxila at the age of sixteen. The ancient and the most revered scriptures, and the Eighteen Silpas or Arts, which included skills such as archery, hunting, and elephant lore, were taught, in addition to its law school, medical school, and school of military science.[65] Students came to Taxila from far-off places such as Kashi, Kosala and Magadha, in spite of the long and arduous journey they had to undergo, on account of the excellence of the learned teachers there, all recognised as authorities on their respective subjects.[66][67]

Notable students and teachers

Taxila had great influence on Hindu culture and the Sanskrit language. It is perhaps best known for its association with Chanakya, also known as Kautilya, the strategist who guided Chandragupta Maurya and assisted in the founding of the Mauryan empire. Chanakya's Arthashastra (The knowledge of Economics) is said to have been composed in Taxila.[68][69] The Ayurvedic healer Charaka also studied at Taxila.[65] He also started teaching at Taxila in the later period.[70] Pāṇini, the grammarian who codified the rules that would define Classical Sanskrit, has also been part of the community at Taxila.[71]

The institution is significant in Buddhist tradition since it is believed that the Mahāyāna branch of Buddhism took shape there.[72] Jīvaka, the court physician of the Magadha emperor Bimbisara who once cured the Buddha, and the Buddhism-supporting ruler of Kosala, Prasenajit, are some important personalities mentioned in Pali texts who studied at Taxila.[73]

No external authorities like kings or local leaders subjected the scholastic activities at Taxila to their control. Each teacher formed his own institution, enjoying complete autonomy in work, teaching as many students as he liked and teaching subjects he liked without conforming to any centralised syllabus. Study terminated when the teacher was satisfied with the student's level of achievement. In general, specialisation in a subject took around eight years, though this could be lengthened or shortened in accordance with the intellectual abilities and dedication of the student in question. In most cases the "schools" were located within the teachers' private houses, and at times students were advised to quit their studies if they were unable to fit into the social, intellectual and moral atmosphere there.[74]

Knowledge was considered too sacred to be bartered for money, and hence any stipulation that fees ought to be paid was vigorously condemned. Financial support came from the society at large, as well as from rich merchants and wealthy parents. Though the number of students studying under a single Guru sometimes numbered in the hundreds, teachers did not deny education even if the student was poor; free boarding and lodging was provided, and students had to do manual work in the household. Paying students, such as princes, were taught during the day, while non-paying ones were taught at night.[75] Gurudakshina was usually expected at the completion of a student's studies, but it was essentially a mere token of respect and gratitude - many times being nothing more than a turban, a pair of sandals, or an umbrella. In cases of poor students being unable to afford even that, they could approach the king, who would then step in and provide something. Not providing a poor student a means to supply his Guru's Dakshina was considered the greatest slur on a King's reputation.[76]

Examinations were treated as superfluous, and not considered part of the requirements to complete one's studies. The process of teaching was critical and thorough- unless one unit was mastered completely, the student was not allowed to proceed to the next. No convocations were held upon completion, and no written "degrees" were awarded, since it was believed that knowledge was its own reward. Using knowledge for earning a living or for any selfish end was considered sacrilegious.[74]

Students arriving at Taxila usually had completed their primary education at home (until the age of eight), and their secondary education in the Ashrams (between the ages of eight and twelve), and therefore came to Taxila chiefly to reach the ends of knowledge in specific disciplines.[77]

Ruins

The sites of a number of important cities noted in ancient Indian texts were identified by scholars early in the 19th century. The lost city of Taxila, however, was not identified until later, in 1863-64. Its identification was made difficult partly due to errors in the distances recorded by Pliny in his Naturalis Historia which pointed to a location somewhere on the Haro river, two days march from the Indus. Alexander Cunningham, the founder and the first director-general of the Archaeological Survey of India, noticed that this position did not agree with the descriptions provided in the itineraries of Chinese pilgrims and in particular, that of Xuanzang, the 7th-century Buddhist monk. Unlike Pliny, these sources noted that the journey to Taxila from the Indus took three days and not two. Cunningham's subsequent explorations in 1863–64 of a site at Shah-dheri convinced him that his hypothesis was correct.[78]

Now as Hwen Thsang, on his return to China, was accompanied by laden elephants, his three days' journey from Takhshasila [sic] to the Indus at Utakhanda, or Ohind, must necessarily have been of the same length as those of modern days, and, consequently, the site of the city must be looked for somewhere in the neighbourhood of Kâla-ka-sarâi. This site is found near Shah-dheri, just one mile to the north-east of Kâla-ka-sarâi, in the extensive ruins of a fortified city, around which I was able to trace no less than 55 stupas, of which two are as large as the great Manikyala tope, twenty eight monasteries, and nine temples.

— Alexander Cunningham, [79]

Taxila's archaeological sites lie near modern Taxila about 35 km (22 mi) northwest of the city of Rawalpindi.[19] The sites were first excavated by John Marshall, who worked at Taxila over a period of twenty years from 1913.[80]

The vast archaeological site includes neolithic remains dating to 3360 BCE, and Early Harappan remains dating to 2900–2600 BCE at Sarai Kala.[30] Taxila, however, is most famous for ruins of several settlements, the earliest dating from around 1000 BCE. It is also known for its collection of Buddhist religious monuments, including the Dharmarajika stupa, the Jaulian monastery, and the Mohra Muradu monastery.

The main ruins of Taxila include four major cities, each belonging to a distinct time period, at three different sites. The earliest settlement at Taxila is found in the Hathial section, which yielded pottery shards that date from as early as the late 2nd millennium BCE to the 6th century BCE. The Bhir Mound ruins at the site date from the 6th century BCE, and are adjacent to Hathial. The ruins of Sirkap date to the 2nd century BCE, and were built by the region's Greco-Bactrian kings who ruled in the region following Alexander the Great's invasion of the region in 326 BCE. The third and most recent settlement is that of Sirsukh, which was built by rulers of the Kushan empire, who ruled from nearby Purushapura (modern Peshawar).

World Heritage Site

Taxila was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980 in particular for the ruins of the four settlement sites which "reveal the pattern of urban evolution on the Indian subcontinent through more than five centuries". The serial site includes a number of monuments and other historical places of note in the area besides the four settlements at Bhir, Saraikala, Sirkap, and Sirsukh.[81] They number 18 in all:[82]

- Khanpur Cave

- Saraikala, prehistoric mound

- Bhir Mound

- Sirkap (fortified city)

- Sirsukh (fortified ruined city)

- Dharmarajika stupa and monastery

- Khader Mohra (Akhuri)

- Kalawan group of buildings

- Giri complex of monuments

- Kunala stupa and monastery

- Jandial complex

- Lalchak and Badalpur Buddhist stuppa

- Mohra Moradu stupa and monastery

- Pippala stupa and monastery

- Jaulian stupa and monastery

- Lalchak mounds

- Buddhist remains around Bhallar stupa

- Giri Mosque and tombs

In a 2010 report, Global Heritage Fund identified Taxila as one of 12 worldwide sites most "on the Verge" of irreparable loss and damage, citing insufficient management, development pressure, looting, and war and conflict as primary threats.[83] In 2017, it was announced that Thailand would assist in conservation efforts at Taxila, as well as at Buddhist sites in the Swat Valley.[84]

Gallery

- A coin from 2nd century BCE Taxila.

The Indo-Greek king Antialcidas ruled in Taxila around 100 BCE, according to the Heliodorus pillar inscription.

The Indo-Greek king Antialcidas ruled in Taxila around 100 BCE, according to the Heliodorus pillar inscription. Jaulian, a World Heritage Site at Taxila.

Jaulian, a World Heritage Site at Taxila. Jaulian silver Buddhist reliquary, with content. British Museum.

Jaulian silver Buddhist reliquary, with content. British Museum.- Jain Temple at Sirkap

Stupa base at Sirkap, decorated with Hindu, Buddhist and Greek temple fronts.

Stupa base at Sirkap, decorated with Hindu, Buddhist and Greek temple fronts.- Stupa in Taxila.

- A Taxila coin, 200–100 BCE. British Museum.

- Archaeological artifacts from the Indo-Greek strata at Taxila from John Marshall "Taxila Archeological excavations").

Notes

- Raymond Allchin, Bridget Allchin, The Rise of Civilization in India. Cambridge University Press, 1982 p.314 ISBN 052128550X ("The first city of Taxila at Hathial goes back at least to c. 1000 B.C.")

- The name for the city of Taxila as it appears on the Heliodorus Pillar inscription, circa 100 BC.

- UNESCO World Heritage Site, 1980. Taxila: Multiple Locations. Retrieved 13 January 2007.

- Windsor, Antonia (17 October 2006). "Out of the rubble". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- Needham, Joseph (2004). Within the Four Seas: The Dialogue of East and West. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-36166-8.

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A History of India (4th ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4.

In the early centuries the centre of Buddhist scholarship was the University of Taxila.

- Balakrishnan Muniapan, Junaid M. Shaikh (2007), "Lessons in corporate governance from Kautilya's Arthashastra in ancient India", World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 3 (1):

"Kautilya was also a Professor of Politics and Economics at Taxila University. Taxila University is one of the oldest known universities in the world and it was the chief learning centre in ancient India."

- Radha Kumud Mookerji (2nd ed. 1951; reprint 1989), ''Ancient Indian Education: Brahmanical and Buddhist (p. 478), Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 81-208-0423-6:

"Thus the various centres of learning in different parts of the country became affiliated, as it were, to the educational centre, or the central university, of Taxila which exercised a kind of intellectual suzerainty over the wide world of letters in India."

- Radha Kumud Mookerji (2nd ed. 1951; reprint 1989), Ancient Indian Education: Brahmanical and Buddhist (p. 479), Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 81-208-0423-6:

"This shows that Taxila was a seat not of elementary, but higher, education, of colleges or a university as distinguished from schools."

- Anant Sadashiv Altekar (1934; reprint 1965), Education in Ancient India, Sixth Edition, Revised & Enlarged, Nand Kishore & Bros, Varanasi:

"It may be observed at the outset that Taxila did not possess any colleges or university in the modern sense of the term."

- F. W. Thomas (1944), in John Marshall (1951; 1975 reprint), Taxila, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi:

"We come across several Jātaka stories about the students and teachers of Takshaśilā, but not a single episode even remotely suggests that the different 'world renowned' teachers living in that city belonged to a particular college or university of the modern type."

- Taxila Archived 22 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine (2007), Encyclopædia Britannica:

"Taxila, besides being a provincial seat, was also a centre of learning. It was not a university town with lecture halls and residential quarters, such as have been found at Nalanda in the Indian state of Bihar."

- "Nalanda" (2007). Encarta.

- "Nalanda" (2001). Columbia Encyclopedia.

- Global Heritage Fund | GHF

- "Feature: Pakistan in efforts to rejuvenate Taxila, one of most important archaeological sites in Asia - Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Taxila: an illustration of fascinating influences of multiple civilisations - Daily Times". Daily Times. 13 May 2018.

- Scharfe 2002, pp. 140,141.

- "Taxila, ancient city, Pakistan". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- Lahiri 2015, Chapter 3.

- Marshall 1951, p. 1.

- Kosambi 1975, p. 129.

- Saifur Rahman Dar. "Antiquity, Meaning and Origin of the Name Takshashila or Taxila". The Panjab Past and Present. 11 (2): 11.

- Raychaudhuri, Hem Chandra (1923), Political history of ancient India, from the accession of Parikshit to the extinction of the Gupta dynasty, pp. 17–18, 25–26

- Davis 2014, p. 38.

- Kosambi 1975, p. 126.

- Marshall 1960, p. 10.

- Malalasekera 1937, Telapatta Jātaka (No.96): "The Bodhisatta was once the youngest of one hundred sons of the king of Benares. He heard from the Pacceka Buddhas, who took their meals in the palace, that he would become king of Takkasilā if he could reach it without falling a prey to the ogresses who waylaid travellers in the forest. Thereupon, he set out with five of his brothers who wished to accompany him. On the way through the forest the five in succession succumbed to the charms of the ogresses, and were devoured. One ogress followed the Bodhisatta right up to the gates of Takkasilā, where the king took her into the palace, paying no heed to the Bodhisatta's warning. The king succumbed to her wiles, and, during the night, the king and all the inhabitants of the palace were eaten by the ogress and her companions. The people, realising the sagacity and strength of will of the Bodhisatta, made him their king."

- Appleton 2016, pp. 23,82.

- Allchin & Allchin 1988, p. 127.

- Allchin & Allchin 1988, p. 314: "The first city of Taxila at Hathial goes back at least to c. 1000 B.C."

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Taxila". whc.unesco.org.

- Scharfe 2002, p. 141.

- Mohan Pant, Shūji Funo, Stupa and Swastika: Historical Urban Planning Principles in Nepal's Kathmandu Valley. NUS Press, 2007 ISBN 9971693720, citing Allchin: 1980

- Petrie, Cameron, (2013). "Taxila", in D. K. Chakrabarti and M. Lal (eds.), History of Ancient India III: The Texts, and Political History and Administration till c. 200 BC, Vivekananda International Foundation, Aryan Books International, Delhi, p. 656.

- "Darius the Great - 8. Travels - Livius". www.livius.org.

- Marshall 1951, p. 83.

- Samad, Rafi U (2011). The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. ISBN 9780875868592.

- Marshall 1951, p. 16-17,30,71.

- Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, § T602.8

- Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, § 5.8

- Mookerji 1988, p. 31.

- Mookerji 1988, p. 22,54.

- Thapar 1997, p. 52.

- Thapar 1997, p. 237.

- Kulke & Rothermund 2004, p. 75.

- Marshall 1951, p. 84.

- Marshall 1951, p. 85.

- Medlycott 1905, Chapter: The Apostle Thomas and Gondophares the Indian King.

- John Marshall, A Guide to Taxila, 4th edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960, pp. 28-30, 69, and 88-89.

- Kulke & Rothermund 2004, p. 80.

- Kumar, Sanjeev (2017). Treasures of the Gupta Empire - A Catalogue of Coins of the Gupta Dynasty.

- Ancient India by Ramesh Chandra Majumdar

- Needham 2005, p. 135.

- A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms, Being an Account by the Chinese Monk Fa-Hsien of his Travels in India and Ceylon in Search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline, Chapter 11

- Marshall 1951, p. 86.

- A Guide to Taxila. Cambridge University Press. 20 June 2013. pp. 39, 46. ISBN 9781107615441.

- Elizabeth Errington, Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis. Persepolis to the Punjab: Exploring Ancient Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan. British Museum Press. p. 134.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- The Panjab Past and Present - Volume 11 - Page 18

- Pakistan Journal of History and Culture - Volumes 4-5 - Page 11

- Kulke & Rothermund 2004, p. 157.

- Mookerji 1989, pp. 478,479.

- Altekar 1965, p. 109: "It may be observed at the outset that Taxila did not possess any colleges or university in the modern sense of the term."

- Marshall 1951, p. 81: "We come across several Jātaka stories about the students and teachers of Takshaśilā, but not a single episode even remotely suggests that the different 'world renowned' teachers living in that city belonged to a particular college or university of the modern type."|author=F. W. Thomas (1944)

- Mookerji 1989, pp. 478–489.

- Prakash 1964: "Students from Magadha traversed the vast distances of northern India in order to join the schools and colleges of Taxila. We learn from Pali texts that Brahmana youths, Khattiya princes and sons of setthis from Rajagriha, Kashi, Kosala and other places went to Taxila for learning the Vedas and eighteen sciences and arts."

- Apte, p. 9.

- Kautilya. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived 10 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Mookerji 1988, p. 17.

- "Takshila university". Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- Prakash 1964: "Pāṇini and Kautilya, two masterminds of ancient times, were also brought up in the academic traditions of Taxila"

- Gupta, Aryan. "Taxila and Mahayana Buddhism". School near Heart.

- Prakash 1964: "Likewise, Jivaka, the famous physician of Bimbisara who cured the Buddha, learnt the science of medicine under a far-famed teacher at Taxila and on his return was appointed court-physician at Magadha. Another illustrious product of Taxila was the enlightened ruler of Kosala, Prasenajit, who is intimately associated with the events of the time of the Buddha."

- Apte, pp. 9,10.

- Apte, pp. 16,17.

- Apte, pp. 18,19.

- Apte, p. 11.

- Upinder Singh 2008, p. 265.

- Cunningham 1871, p. 105.

- Wheeler 2008.

- "Taxila". UNESCO. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Taxila Map". whc.unesco.org. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- "Global Heritage Fund - GHF". Archived from the original on 20 August 2012.

- "Thailand to provide assistance for restoration of Ghandhara Archelogical [sic] sites". The Nation. 16 January 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

References

- Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1989) [1951]. Ancient Indian education: Brahmanical and Buddhist (2nd ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0423-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988) [1966]. Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4th ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0405-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A History of India (4th ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Allchin, Bridget; Allchin, Raymond (1988). The rise of civilization in India and Pakistan. Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521285506.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lahiri, Nayanjot (2015). Ashoka in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674915251. Retrieved 16 May 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scharfe, Hartmut (2002). Education in ancient India. Leiden [u.a.]: Brill. ISBN 9789004125568.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thapar, Romila (1997). Aśoka and the decline of the Mauryas (Rev. ed.). Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-563932-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Medlycott, A.E. (1905). India and the Apostle Thomas. London: David Nutt.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Altekar, Anant Sadashiv (1965). Education in Ancient India (6th ed.). Nand Kishore.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Needham, Joseph (2005) [1969]. Within the four seas : the dialogue of East and West. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-36166-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Apte, DG (c. 1950). Universities in ancient India. Baroda: Faculty of Education and Psychology, Maharaja Sayajirao University.

- Prakash, Buddha (1964). Political And Social Movements in Ancient Punjab. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120824584.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kosambi, Damodar Dharmanand (1975) [first published 1956]. An Introduction to the Study of Indian History (Revised Second ed.). Bombay: Popular Prakashan. p. 126.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marshall, John (2013) [1960]. A guide to Taxila (Fourth ed.). ISBN 9781107615441.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marshall, John (1951). Taxila: Structural remains – Volume 1. University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trautmann, Thomas R. (1971), Kauṭilya and the Arthaśāstra: a statistical investigation of the authorship and evolution of the text, BrillCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A history of ancient and early medieval India : from the Stone Age to the 12th century. New Delhi: Pearson Education. ISBN 9788131711200.

- Cunningham, Alexander (1871). The Ancient Geography of India: The Buddhist Period, Including the Campaigns of Alexander, and the Travels of Hwen-Thsang. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Pres. ISBN 9781108056458.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, Richard H. (2014). The "Bhagavad Gita": A Biography. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400851973.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Malalasekera, G. P. (1937). Dictionary of Pali Proper Names. Asian Educational Services (published 2003). ISBN 9788120618237.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Appleton, Naomi (2016). Jataka Stories in Theravada Buddhism: Narrating the Bodhisatta Path. Routledge. ISBN 9781317111252.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wheeler, Mortimer (2004). "Marshall, Sir John Hubert (1876–1958)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34896. Retrieved 4 July 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Allchin, F. Raymond (1993). "The Urban Position of Taxila and Its Place in Northwest India-Pakistan". Studies in the History of Art. 31: 69–81. JSTOR 42620473.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Taxila. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Taxila. |

- Explore Taxila with Google Earth on Global Heritage Network

- Guide to Historic Taxila by Ahmad Hasan Dani in 10 chapters

- "Taxila", by Jona Lendering

- Map of Gandhara archaeological sites, from the Huntington Collection, Ohio State University (large file)

- Taxila: An Ancient Indian University by S. Srikanta Sastri

- John Marshall, A guide to Taxila (1918) on Archive.org

- Telapatta Jataka also known as the Takkasila Jataka