Syria Palaestina

Syria Palaestina (Latin: [ˈsʏ.ri.a pa.ɫ̪ae̯sˈt̪iː.na]; Koinē Greek: Συρία ἡ Παλαιστίνη, romanized: Syría hē Palaistínē, Koine Greek: [syˈri.a (h)e̝ pa.lɛsˈt̪i.ne̝]) was a Roman province between 135 AD and about 390.[1] It was established by the merger of Roman Syria and Roman Judaea, following the suppression of the Bar Kokhba revolt in 135 AD. Shortly after 193, the northern regions were split off as Syria Coele in the north and Phoenice in the south, and the province Syria Palaestina was reduced to Judea. The earliest numismatic evidence for the name Syria Palaestina comes from the period of emperor Marcus Aurelius, although the Classical Greek version of name has been recorded in usage since at least the 5th century BC.

| Provincia Syria Palaestina ἐπαρχία Συρίας τῆς Παλαιστίνης | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province of the Roman Empire | |||||||||||||||||

| 135–390 | |||||||||||||||||

Syria and Palaestina are joined until c.194 | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Antioch | ||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical antiquity | ||||||||||||||||

• End of the Bar Kokhba revolt | 135 | ||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 390 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Background

Syria was an early Roman province, annexed to the Roman Republic in 64 BC by Pompey in the Third Mithridatic War, following the defeat of Armenian King Tigranes the Great.[2] Following the partition of the Herodian kingdom into tetrarchies in 6 AD, it was gradually absorbed into Roman provinces, with Roman Syria annexing Iturea and Trachonitis.

The Roman province of Judea incorporated the regions of Judea, Samaria, and Idumea, and extended over parts of the former regions of the Hasmonean and Herodian kingdoms of Israel. It was named after Herod Archelaus's Tetrarchy of Judea, but the Roman province encompassed a much larger territory.

The capital of Roman Syria was established in Antioch from the very beginning of Roman rule, while the capital of the Judaea province was shifted to Caesarea Maritima, which, according to historian H. H. Ben-Sasson, had been the "administrative capital" of the region beginning in 6 AD.[3]

Judea province was the scene of unrest at its founding in 6 AD during the Census of Quirinius and several wars were fought in its history, known as the Jewish–Roman wars. The Temple was destroyed in 70 AD as part of the First Jewish–Roman War resulting in the institution of the Fiscus Judaicus. The Provinces of Judaea and Syria were key scenes of an increasing conflict between Judaean and Hellenistic population, which exploded into full scale Jewish–Roman wars, beginning with the First Jewish–Roman War of 66–70. Disturbances followed throughout the region during the Kitos War in 117–118. Between 132–135, Simon bar Kokhba led a revolt against the Roman Empire, controlling parts of Judea, for three years. As a result, Hadrian sent Sextus Julius Severus to the region, who brutally crushed the revolt. Shortly before or after the Bar Kokhba's revolt (132–135), the Roman Emperor Hadrian changed the name of the Judea province and merged it with Roman Syria to form Syria Palaestina, and founded Aelia Capitolina on the ruins of Jerusalem, which some scholars conclude was done in an attempt to remove the relationship of the Jewish people to the region.[4][5][6][7]

Hadrian's connection to the name change and the reason behind it is disputed.[8][9]

History

Consolidation

After crushing the Bar Kokhba revolt, the Roman Emperor Hadrian applied the name Syria Palestina to the entire region that had formerly included Judea province. Some allege that Hadrian wanted to choose a name that revived the ancient name of Palestine and combine it with that of the neighboring province of Syria in an attempt to suppress Jewish connection to the land, but this is not supported by the historical record. Besides a lack of any primary source evidence to indicate Hadrian's alleged ulterior motives for a routine Roman practice of consolidating, re-organizing, and re-naming provinces, the timeline shows the roots of the name Syria Palaestina in the region in fact predate those of Judea. The name Judea had been derived from the Kingdom of Judah which had arisen in the region in the 9th century BC, in the 8th century becoming a vassal of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC). The name Philistia (Palestine) was derived from the Philistines, a people who had arisen in the land between the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age in the 12th century BC. Both the Judeans and Philistines were conquered and exiled by Nebuchadnezzar II between 604 and 586 BC upon the rise of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626–539 BC).[10]

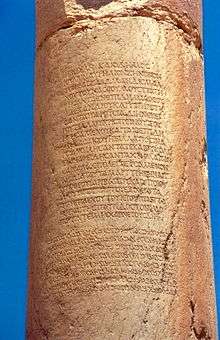

Furthermore, the juxtaposition of Syria and Palestina together into combined name Syria Palaestina predates Hadrian's naming decision by at least 6 centuries, the term already long in use in Classical Greek historical literature to refer to Palestine as part of a broader Syrian region encompassing the Levant from Cappadocia and Cilicia in the north down through Phoenicia and Palestina, bordering Egypt to the south. Herodotus, writing The Histories in the Ionic dialect of Ancient Greek in 440 BC, repeatedly refers to Syria Palaestina (Ionic Greek: Συρίη ἡ Παλαιστίνη, romanized: Suríē hē Palaistínē) as a combined name single phrase.[11] [12]

The city of Aelia Capitolina was built by the emperor Hadrian on the ruins of Jerusalem. The capital of the enlarged province remained in Antiochia.

In 193, the province of Syria-Coele was split from Syria Palaestina. In the 3rd century, Syrians even reached for imperial power, with the Severan dynasty. Syria was of crucial strategic importance during the Crisis of the Third Century.

Conflict with Sassanids and emergence of the Palmyrene Empire

Beginning in 212, Palmyra's trade diminished as the Sassanids occupied the mouth of the Tigris and the Euphrates. In 232, the Syrian Legion rebelled against the Roman Empire, but the uprising went unsuccessful.

Septimius Odaenathus, a Prince of the Aramean state of Palmyra, was appointed by Valerian as the governor of the province of Syria Palaestina. After Valerian was captured by the Sassanids in 260, and died in captivity in Bishapur, Odaenathus campaigned as far as Ctesiphon (near modern-day Baghdad) for revenge, invading the city twice. When Odaenathus was assassinated by his nephew Maconius, his wife Septimia Zenobia took power, ruling Palmyra on behalf of her son, Vabalathus.

Zenobia rebelled against Roman authority with the help of Cassius Longinus and took over Bosra and lands as far to the west as Egypt, establishing the short-lived Palmyrene Empire. Next, she took Antioch and large sections of Asia Minor to the north. In 272, the Roman Emperor Aurelian finally restored Roman control and Palmyra was besieged and sacked, never to recover her former glory. Aurelian captured Zenobia, bringing her back to Rome. He paraded her in golden chains in the presence of the senator Marcellus Petrus Nutenus, but allowed her to retire to a villa in Tibur, where she took an active part in society for years. A legionary fortress was established in Palmyra and although no longer an important trade center, it nevertheless remained an important junction of Roman roads in the Syrian desert.[13]

Diocletian built the Camp of Diocletian in the city of Palmyra to harbor even more legions and walled it in to try and save it from the Sassanid threat. The Byzantine period following the Roman Empire only resulted in the building of a few churches; much of the city went to ruin.

Reorganization

In circa 390, Syria Palaestina was reorganised into several administrative units: Palaestina Prima, Palaestina Secunda, and Palaestina Tertia (in the 6th century),[14] Syria Prima and Phoenice and Phoenice Lebanensis. All were included within the larger Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Diocese of the East, together with the provinces of Isauria, Cilicia, Cyprus (until 536), Euphratensis, Mesopotamia, Osroene, and Arabia Petraea.

Palaestina Prima consisted of Judea, Samaria, the Paralia, and Peraea, with the governor residing in Caesarea. Palaestina Secunda consisted of the Galilee, the lower Jezreel Valley, the regions east of Galilee, and the western part of the former Decapolis, with the seat of government at Scythopolis. Palaestina Tertia included the Negev, southern Transjordan part of Arabia, and most of Sinai, with Petra as the usual residence of the governor. Palestina Tertia was also known as Palaestina Salutaris.[15]

Religion

Roman cult

After the Jewish–Roman wars (66–135), which Epiphanius believed the Cenacle survived,[16] the significance of Jerusalem to Christians entered a period of decline, Jerusalem having been temporarily converted to the pagan Aelia Capitolina, but interest resumed again with the pilgrimage of Helena (the mother of Constantine the Great) to the Holy Land c. 326–28.

New pagan cities were founded in Judea at Eleutheropolis (Bayt Jibrin), Diopolis (Lydd), and Nicopolis (Emmaus).[17][18]

Second Temple in Judaism

Second Temple Judaism is Judaism between the construction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, c. 515 BC, and its destruction by the Romans in 70 AD. The development of the Hebrew Bible canon, the synagogue, Jewish apocalyptic expectations for the future, and Christianity, can all be traced to the Second Temple period.

Following the Jewish–Roman wars, many Jews left the country altogether for the Diaspora communities, and large numbers of prisoners of war were sold as slaves throughout the Empire. This changed the perception of Jerusalem as the center of faith and autonomous Jewish communities shifted from centralized religious authority into more dispersed one.

Early Christianity

The Romans destroyed the Jewish community of the Church in Jerusalem, which had existed since the time of Jesus.[19] Traditionally it is believed the Jerusalem Christians waited out the Jewish–Roman wars in Pella in the Decapolis.

The line of Jewish bishops in Jerusalem, which is claimed to have started with Jesus's brother James the Righteous as its first bishop, ceased to exist, within the Empire. Hans Kung in "Islam: Past Present and Future", suggests that the Jewish Christians sought refuge in Arabia and he quotes with approval Clemen et al.:

"This produces the paradox of truly historic significance that while Jewish Christianity was swallowed up in the Christian church, it preserved itself in Islam."[20]

Christianity was practiced in secret and the Hellenization of Palaestina continued under Septimius Severus (193–211 AD).[17]

Demographics

As a large province, the territory of Syria-Palaestina comprised the Levant and the western part of Mesopotamia. In the Northern Levant, areas we define now as modern-day Syria, Lebanon and Southern Turkey, the demographics consisted of mixed and assimilated population groups of Canaanites, Aramaeans, Greeks, Romans and Jews, alongside Arab societies of Itureans and later the Ghassanids who migrated to the area later on during the 3rd century, at the Golan heights although it's worth mentioning that the Arab societies weren't as assimilated to the populace inhabiting the northern Levant as the other mentioned groups.

Assyrians were still populating western Mesopotamia and indeed Mesopotamia as a whole, while nomad Arameans, Nabateans and Bedouins, were thriving in the south Syrian Desert. In Southern Levant, until about 200 AD, and despite the genocide of Jewish–Roman wars, Jews had formed a majority of the population.[21]

By the beginning of the Byzantine period (disestablishment of Syria-Palaestina), the Jews had become a minority and were living alongside Samaritans, pagan Greco-Syriacs and a large Syriac Christian community.

See also

References

- Lehmann, Clayton Miles (Summer 1998). "Palestine: History: 135–337: Syria Palaestina and the Tetrarchy". The On-line Encyclopedia of the Roman Provinces. University of South Dakota. Archived from the original on 2009-08-11. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- Martin Sicker. Between Rome and Jerusalem: 300 years of Roman-Judaean relations. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- A History of the Jewish People, H. H. Ben-Sasson editor, 1976, page 247: "When Judea was converted into a Roman province [in 6 AD, page 246], Jerusalem ceased to be the administrative capital of the country. The Romans moved the governmental residence and military headquarters to Caesarea. The centre of government was thus removed from Jerusalem, and the administration became increasingly based on inhabitants of the hellenistic cities (Sebaste, Caesarea and others)."

- Cassius, Dio (1927). Dio's Roman History, Volume VIII, Books 61-70. World: Loeb Classical Library. p. 447. ISBN 9780674991958.

- H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, Harvard University Press, 1976, ISBN 0-674-39731-2, page 334: "In an effort to wipe out all memory of the bond between the Jews and the land, Hadrian changed the name of the province from Iudaea to Syria-Palestina, a name that became common in non-Jewish literature."

- Ariel Lewin. The archaeology of Ancient Judea and Palestine. Getty Publications, 2005 p. 33. "It seems clear that by choosing a seemingly neutral name - one juxtaposing that of a neighboring province with the revived name of an ancient geographical entity (Palestine), already known from the writings of Herodotus - Hadrian was intending to suppress any connection between the Jewish people and that land." ISBN 0-89236-800-4

- Ronald Syme suggested the name change preceded the revolt; he writes "Hadrian was in those parts in 129 and 130. He abolished the name of Jerusalem, refounding the place as a colony, Aelia Capitolina. That helped to provoke the rebellion. The supersession of the ethnical term by the geographical may also reflect Hadrian's decided opinions about Jews." Syme, Ronald (1962). "The Wrong Marcius Turbo". The Journal of Roman Studies. 52: 87–96. ISSN 0075-4358. JSTOR 297879. (page 90)

- Feldman 1990, p. 19: "While it is true that there is no evidence as to precisely who changed the name of Judaea to Palestine and precisely when this was done, circumstantial evidence would seem to point to Hadrian himself, since he is, it would seem, responsible for a number of decrees that sought to crush the national and religious spirit of thejews, whether these decrees were responsible for the uprising or were the result of it. In the first place, he refounded Jerusalem as a Graeco-Roman city under the name of Aelia Capitolina. He also erected on the site of the Temple another temple to Zeus."

- Jacobson 2001, p. 44-45: "Hadrian officially renamed Judea Syria Palaestina after his Roman armies suppressed the Bar-Kokhba Revolt (the Second Jewish Revolt) in 135 C.E.; this is commonly viewed as a move intended to sever the connection of the Jews to their historical homeland. However, that Jewish writers such as Philo, in particular, and Josephus, who flourished while Judea was still formally in existence, used the name Palestine for the Land of Israel in their Greek works, suggests that this interpretation of history is mistaken. Hadrian’s choice of Syria Palaestina may be more correctly seen as a rationalization of the name of the new province, in accordance with its area being far larger than geographical Judea. Indeed, Syria Palaestina had an ancient pedigree that was intimately linked with the area of greater Israel."

- DNA Begins to Unlock Secrets of the Ancient Philistines

- s:History of Herodotus/Book 3

Herodotus. "Herodotus III.91".III.91: The country reaching from the city of Posideium (built by Amphilochus, son of Amphiaraus, on the confines of Syria and Cilicia) to the borders of Egypt, excluding therefrom a district which belonged to Arabia and was free from tax, paid a tribute of three hundred and fifty talents. All Phoenicia, Palestine-Syria, and Cyprus, were herein contained.

- , s:History of Herodotus/Book 4

Herodotus. "Herodotus IV.39".IV.39: Between Persia and Phoenicia lies a broad and ample tract of country, after which the region I am describing skirts our sea, stretching from Phoenicia along the coast of Palestine-Syria till it comes to Egypt, where it terminates.

- Isaac (2000), p. 165

- Thomas A. Idniopulos (1998). "Weathered by Miracles: A History of Palestine From Bonaparte and Muhammad Ali to Ben-Gurion and the Mufti". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- "Roman Arabia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Jerusalem (A.D. 71-1099): "Epiphanius (died 403) says..."

- Shahin, Mariam (2005) Palestine: a Guide. Interlink Books ISBN 1-56656-557-X, p. 7

- Encyclopædia Britannica (2007). Palestine. In Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-08-12 from [http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-45053.

- Whealey, J. (2008) "Eusebius and the Jewish Authors: His Citation Technique in an Apologetic Context" (Journal of Theological Studies; Vol 59: 359-362)

- C. Clemen, T. Andrae and H.H. Schraeder, p. 342

- Scholastic Library Publishing (May 2006). Encyclopedia Americana. Scholastic Library Pub. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-7172-0139-6. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

Bibliography

- Nicole Belayche, "Foundation myths in Roman Palestine. Traditions and reworking", in Ton Derks, Nico Roymans (ed.), Ethnic Constructs in Antiquity: The Role of Power and Tradition (Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 2009) (Amsterdam Archaeological Studies, 13), 167-188.