Christian pilgrimage

Christianity has a strong tradition of pilgrimages, both to sites relevant to the New Testament narrative (especially in the Holy Land) and to sites associated with later saints or miracles.

Traditions of Christian pilgrimage

Christian pilgrimage was first made to sites connected with the birth, life, crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus. Aside from the early example of Origen in the third century, surviving descriptions of Christian pilgrimages to the Holy Land date from the 4th century, when pilgrimage was encouraged by church fathers including Saint Jerome, and established by Saint Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great.

The purpose of Christian pilgrimage was summarized by Pope Benedict XVI this way:

To go on pilgrimage is not simply to visit a place to admire its treasures of nature, art or history. To go on pilgrimage really means to step out of ourselves in order to encounter God where he has revealed himself, where his grace has shone with particular splendour and produced rich fruits of conversion and holiness among those who believe. Above all, Christians go on pilgrimage to the Holy Land, to the places associated with the Lord’s passion, death and resurrection. They go to Rome, the city of the martyrdom of Peter and Paul, and also to Compostela, which, associated with the memory of Saint James, has welcomed pilgrims from throughout the world who desire to strengthen their spirit with the Apostle’s witness of faith and love.[1]

Pilgrimages are made to Rome and other sites associated with the apostles, saints and Christian martyrs, as well as to places where there have been apparitions of the Virgin Mary. A popular pilgrimage journey is along the Way of St. James to the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral, in Galicia, Spain, where the shrine of the apostle James is located. Also a combined pilgrimage is held every seven years in the three nearby towns of Maastricht, Aachen and Kornelimünster where many important relics could be seen (see: Pilgrimage of the Relics, Maastricht).

Motivations of pilgrims

The motivations which draw today's visitors to Christian sacred sites can be mixed: faith-based, spiritual in a general way, with cultural interests, etc. This diversity has become an important factor in the management and pastoral care of Christian pilgrimage, as recent research on international sanctuaries and much-visited churches has shown.[2]

Ancient Pilgrimages

Rome

Rome has been a major Christian pilgrimage site since the Middle Ages. Pilgrimages to Rome can involve visits to a large number of sites, both within the Vatican City and in Italian territory. A popular stopping point is the Pilate's stairs: these are, according to the Christian tradition, the steps that led up to the praetorium of Pontius Pilate in Jerusalem, which Jesus Christ stood on during his Passion on his way to trial.[3] The stairs were, reputedly, brought to Rome by St. Helena in the 4th Century. For centuries, the Scala Santa has attracted Christian pilgrims who wished to honour the Passion of Jesus.

Several catacombs built in the Roman age are also the object of pilgrimage, where Christians prayed, buried their dead and performed worship during periods of persecution. And various national churches (among them San Luigi dei francesi and Santa Maria dell'Anima), or churches associated with individual religious orders, such as the Jesuit Church of the Gesù and Sant'Ignazio.

Traditionally, pilgrims in Rome visit the seven pilgrim churches (Italian: Le sette chiese) in 24 hours. This custom, mandatory for each pilgrim in the Middle Ages, was codified in the 16th century by Saint Philip Neri. The seven churches are the four major Basilicas (St Peter in Vatican, St Paul outside the Walls, St John in Lateran and Santa Maria Maggiore), while the other three are San Lorenzo fuori le mura (a palaeochristian Basilica), Santa Croce in Gerusalemme (a church founded by Helena, the mother of Constantine, which hosts fragments of wood attributed to the holy cross) and San Sebastiano fuori le mura (which lies on the Appian Way and is built above Roman catacombs).

Jewish pilgrimage to Rome

Rabbinic literature has some descriptions of several early visits by Jews to Rome. The Talmud and Midrash recount rabbinic embassies that journey to Rome to connect with and vouch for the rights of the Jewish community.[4] Jewish people also traveled to Rome to visit locations that highlighted Jewish culture, such as the arch of Titus depicting the spoils of Jerusalem,[5] and the Temple of Peace, which housed the looted Jewish temple cult objects.[6] It is surmised that some Jewish visitors, particularly those of religious prestige, would have traveled to Rome to view the displayed cult objects as a form of neo-pilgrimage, as pilgrimage to the Jewish temple itself was no longer possible.

It is unknown what happened to the Jewish temple objects after a fire destroyed the Temple of Peace in 192 CE, but it is possible that they were saved or had replicas produced of them to use in Christian propaganda that was put on display for Christian followers.[7][8]

Canterbury, England

After the murder of the Archbishop Thomas Becket at the cathedral in 1170, Canterbury became one of the most notable towns in Europe, as pilgrims from all parts of Christendom came to visit his shrine.[9] This pilgrimage provided the framework for Geoffrey Chaucer's 14th-century collection of stories, The Canterbury Tales.[10] Canterbury Castle was captured by the French Prince Louis during his 1215 invasion of England, before the death of John caused his English supporters to desert his cause and support the young Henry III.[11]

During the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the city's priory, nunnery and three friaries were closed. St Augustine's Abbey, the 14th richest in England at the time, was surrendered to the Crown, and its church and cloister were levelled. The rest of the abbey was dismantled over the next 15 years, although part of the site was converted to a palace.[12] Thomas Becket's shrine in the Cathedral was demolished and all the gold, silver and jewels were removed to the Tower of London, and Becket's images, name and feasts were obliterated throughout the kingdom, ending the pilgrimages.

Modern Pilgrimages

Holy Land

The first pilgrimages were made to sites connected with the ministry of Jesus. Aside from the early example of Origen who, "in search of the traces of Jesus, the disciples and the prophets",[13] already found local folk prompt to show him the actual location of the Gadarene swine in the mid-3rd century, surviving descriptions of Christian pilgrimages to the Holy Land and Jerusalem date from the 4th century. The Itinerarium Burdigalense ("Bordeaux Itinerary"), the oldest surviving Christian itinerarium, was written by the anonymous "Pilgrim of Bordeaux" recounting the stages of a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in the years 333 and 334.[14]

Pilgrimage was encouraged by church fathers like Saint Jerome and established by Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great. Pilgrimages also began to be made to Rome and other sites associated with the Apostles, Saints and Christian martyrs, as well as to places where there have been apparitions of the Virgin Mary. Pilgrimage to Rome became a common destination for pilgrims from throughout Western Christianity in the medieval period, and important sites were listed in travel-guides such as the 12th-century Mirabilia Urbis Romae.

In the 7th century, the Holy Land fell to the Muslim conquests,[15] and as pilgrimage to the Holy Land now became more difficult for European Christians, major pilgrimage sites developed in Western Europe, notably Santiago de Compostela in the 9th century, though travellers such as Bernard the Pilgrim continued to make the journey to the Holy Land.

Political relationships between the Muslim caliphates and the Christian kingdoms of Europe remained in a state of suspended truce, allowing the continuation of Christian pilgrimages into Muslim-controlled lands, at least in intervals; for example, the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah ordered the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, only to have his successor allow the Byzantine Empire to rebuild it.[16] The Seljuk Turks systematically disrupted Christian pilgrimage routes, which became one of the major factors triggering the crusades later in the 11th century.

The crusades were at first a success, the Crusader states, especially the kingdom of Jerusalem, guaranteeing safe access to the Holy Land for Christian pilgrims during the 12th century, but the enterprise of the crusades was ultimately doomed to failure and the Holy Land was entirely re-conquered by the Ayyubids by the end of the 13th century.

Under the Ottoman Empire travel in Palestine was once again restricted and dangerous. Modern pilgrimages in the Holy Land may be said to have received an early impetus from the scholar Ernest Renan, whose twenty-four days in Palestine, recounted in his Vie de Jésus (published 1863) found the resonance of the New Testament at every turn.

Taizé, France

The commune of Taizé in France, home of the Taizé Community, sees over 100,000 Christian pilgrims each year.[17] As the Taizé Community is an ecumenical Christian community, the pilgrims belong to various Christian denominations, including the Reformed, Catholic, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox, Methodist, Anglican and Oriental Orthodox traditions.[18] Christian pilgrims engage with the brothers and sisters of the Taizé Community in prayer, worship, the study of Sacred Scripture, the promotion of ecumenism, and communal work.[17]

Santiago de Compostela

At some point between 818 and 842,[19] during the reign of Alfonso II of Asturias, bishop Theodemar of Iria (d. 847) claimed to have found some remains which were attributed to Saint James the Greater. Around the place of the discovery a new settlement and centre of pilgrimage emerged, which was known to the author Usuard in 865[20] and by the 10th century was called Compostella.

The cult of Saint James of Compostela was just one of many arising throughout northern Iberia during the 10th and 11th centuries, as rulers encouraged their own region-specific cults, such as Saint Eulalia in Oviedo and Saint Aemilian in Castile.[21] After the centre of Asturian political power moved from Oviedo to León in 910, Compostela became more politically relevant, and several kings of Galicia and of León were acclaimed by the Galician noblemen and crowned and anointed by the local bishop at the cathedral, among them Ordoño IV in 958,[22] Bermudo II in 982, and Alfonso VII in 1111, by which time Compostela had become capital of the Kingdom of Galicia. Later, 12th-century kings were also sepulchered in the cathedral, namely Fernando II and Alfonso IX, last of the Kings of León and Galicia before both kingdoms were united with the Kingdom of Castile.

According to some authors, by the middle years of the 11th century the site had already become a pan-European place of peregrination,[23] while others maintain that the cult to Saint James was before 11–12th centuries an essentially Galician affair, supported by Asturian and Leonese kings to win over faltering Galician loyalties.[21] Santiago would become in the course of the following century a main Catholic shrine second only to Rome and Jerusalem. In the 12th century, under the impulse of bishop Diego Gelmírez, Compostela became an archbishopric, attracting a large and multinational population. Under the rule of this prelate, the townspeople rebelled, headed by the local council, beginning a secular tradition of confrontation by the people of the city—who fought for self-government—against the local bishop, the secular and jurisdictional lord of the city and of its fief, the semi-independent Terra de Santiago ("land of Saint James"). The culminating moment in this confrontation was reached in the 14th century, when the new prelate, the Frenchman Bérenger de Landore, treacherously executed the counselors of the city in his castle of A Rocha Forte ("the strong rock, castle"), after inviting them for talks.

Maastricht-Aachen-Kornelimünster

.jpg)

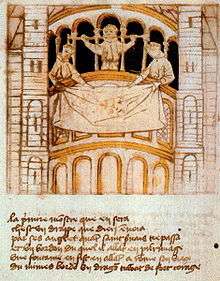

Combined septennial pilgrimages in the Dutch-German towns of Maastricht, Aachen and Kornelimünster were held at least since the 14th century. The German word Heiligtumsfahrt means "journey to the holy relics". In all three places important relics could be seen: in Maastricht relics of the True Cross, the girdle of Mary, the arm of Saint Thomas and various relics of Saint Servatius; in Aachen the nappy and loin cloth of Jesus, the dress of Mary, the decapitation cloth of John the Baptist, and the remains of Charlemagne; and in Kornelimünster the loincloth, the sudarium and the shroud of Jesus, as well as the skull of Pope Cornelius. In Maastricht some relics were shown from the dwarf gallery of St Servatius' Church to the pilgrims gathered in the square; in Aachen the same was done from the purpose-built tower gallery between the dome and the westwork tower of Aachen Cathedral. The popularity of the Maastricht-Aachen-Kornelimünster pilgrimage reached its zenith in the 15th century when up to 140,000 pilgrims visited these towns in mid-July.[24] After a break of about 150 years, the pilgrimages were revived in the 19th century. The Aachen and Kornelimünster pilgrimages are still synchronised but the Maastricht pilgrimage takes place 3 years earlier. In 2011 the Maastricht pilgrimage drew around 175,000 visitors;[25] Aachen had in 2014 around 125,000 pilgrims.[26]

Fátima, Portugal

Marian apparitions are also responsible for tens of millions of Christian pilgrimages worldwide.[27] The Sanctuary of Our Lady of Fátima, in Cova da Iria, Fátima, Portugal, became the most visited sanctuaries in the world with between 14 and 18 million pilgrims per year, for this reason Fátima is often compared to Mecca in terms of pilgrims that visit the holy site in May and October.[28][29]

Lourdes, France

According to believers, the Virgin Mary appeared to Maria Bernada Sobirós (in her native Occitan language) on a total of eighteen occasions at Lourdes (Lorda in her local Occitan language). As a result, Lourdes became a major place of Roman Catholic pilgrimage and of miraculous healings.[30] Today Lourdes receives up to 5,000,000 pilgrims and tourists every season. With about 270 hotels, Lourdes has the second greatest number of hotels per square kilometer in France after Paris.[31] Some of the deluxe hotels like Grand Hotel Moderne, Hotel Grand de la Grotte, Hotel St. Etienne, Hotel Majestic and Hotel Roissy are located here.

Latin America

Latin America has a number of pilgrimage sites, which have been studied by anthropologists, historians, and scholars of religion.[32][33] In Mesoamerica, some predate the arrival of Europeans and were subsequently transformed to Christian pilgrimage sites.[34]

Guadalupe, Mexico

The Hill of Tepeyac now holding the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe outside Mexico City, said to be the site of the apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe.[35]

El Quinche, Ecuador

Located 28 km east of the capital city, Quito, the pilgrimage takes place every 21 November at midnight. More than 800,000 pilgrims walk down a steep slope of 780 metres over the Guayllabamba River and uphill again to the Shrine of Our Lady of the Presentation of El Quinche, located at 2,680 m.a.s.l arriving at 6 a.m.[36] Pope Francis visited El Quinche on July 8, 2015 and spoke to Roman Catholic clergy.[37]

El Cisne, Ecuador

El Cisne is a town in the southern region of Ecuador.[38] Representatives of the city in 1594 requested sculptor Diego de Robles to build the statue of the Virgin of El Cisne which he carved from the wood of a cedar tree. Each year on August 17, thousands of pilgrims gather in El Cisne to carry the statue about 74 km (46 mi) in a procession to the cathedral of Loja, where it is the focus of a great festival on September 8 upon with yet another procession taking place to return it to El Cisne.[39]

Quyllurit'i, Peru

According to the Catholic Church, the festival is in honor of the Lord of Quyllurit'i (Quechua: Taytacha Quyllurit'i, Spanish: Señor de Quyllurit'i) and it originated in the late 18th century. The young native herder Mariano Mayta befriended a mestizo boy named Manuel on the mountain Qullqipunku. Thanks to Manuel, Mariano's herd prospered, so his father sent him to Cusco to buy a new shirt for Manuel. Mariano could not find anything similar, because that kind of cloth was sold only to the archbishop.[40] Learning of this, the bishop of Cusco sent a party to investigate. When they tried to capture Manuel, he was transformed into a bush with an image of Christ crucified hanging from it. Thinking the archbishop's party had harmed his friend, Mariano died on the spot. He was buried under a rock, which became a place of pilgrimage known as the Lord of Quyllurit'i, or "Lord of Star (Brilliant) Snow." An image of Christ was painted on this boulder.

The Quyllurit'i festival attracts thousands of indigenous people from the surrounding regions, made up of Paucartambo groups (Quechua speakers) from the agricultural regions to the northwest of the shrine, and Quispicanchis (Aymara speakers) from the pastoral (herders) regions to the southeast, near Bolivia. Both moieties make an annual pilgrimage to the feast, bringing large troupes of dancers and musicians. Attendees increasingly have included middle-class Peruvians and foreign tourists.

The culminating event for the indigenous non-Christian population takes place after the reappearance of Qullqa in the night sky; it is the rising of the sun after the full moon. Tens of thousands of people kneel to greet the first rays of light as the sun rises above the horizon. Until 2017, the main event for the Church was carried out by ukukus, who climbed glaciers over Qullqipunku at 5,522m.a.s.l. But due to the near disappearance of the glacier, there are fears that the ice may no longer be carried down.[41] The ukukus are considered to be the only ones capable of dealing with the cursed souls said to inhabit the snowfields.[42] The pilgrimage and associated festival was inscribed in 2011 on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.

Copacabana, Bolivia

Before 1534, Copacabana was an outpost of Inca occupation among dozens of other sites in Bolivia. The Incas held it as the key to the very ancient shrine and oracle on the Island of Titicaca, which they had adopted as a place of worship. In 1582, the grandson of Inca ruler Manco Kapac, struck by the sight of the statues of the Blessed Virgin which he saw in some of the churches at La Paz, tried to make one himself, and after many failures, succeeded in producing one of excellent quality, placing it in Copacabana as the statue of the tutelar protectress of the community.

During the Great Indigenous Uprising of 1781, while the church itself was desecrated, the "Camarin", as the chapel is called, remained untouched. Copacabana is the scene of often boisterous indigenous celebrations. The Urinsayas accepted the establishment of the Virgin Mary confraternity, but they did not accept Francisco Tito's carving, and decided to sell it. In La Paz, the picture reached the priest of Copacabana who decided he would bring the image to the people. On 2 February 1583, the image of the Virgin Mary was brought to the area. Since then, a series of miracles[43] attributed to the icon made it one of the oldest Marian shrines in the Americas, On 2 February and 6 August, Church festivals are celebrated with indigenous dances.

See also

- Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society

- HCPT – The Pilgrimage Trust

- List of Christian pilgrimage sites

- List of pilgrimage churches (containing, as of March 2016, only Catholic sites)

Further reading

- Ralf van Bühren, Lorenzo Cantoni, and Silvia De Ascaniis (eds.), Special issue on “Tourism, Religious Identity and Cultural Heritage”, in Church, Communication and Culture 3 (2018), pp. 195–418

- Crumrine, N. Ross and E. Alan Morinis, Pilgrimage in Latin America, Westport CT 1991

- Christian, William A, Local Religion in Sixteenth-Century Spain, Princeton 1989

- Brown, Peter, The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity, Chicago 1981

- Turner, Victor and Edith Turner Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives, New York 1978

References

- https://w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/speeches/2010/november/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20101106_cattedrale-compostela.html

- Ralf van Bühren, The artistic heritage of Christianity. Promotion and reception of identity. Editorial of the first section in the special issue on Tourism, religious identity and cultural heritage, in Church, Communication and Culture 3 (2018), pp. 195–196.

- Steps Jesus walked to trial restored to glory, Daily Telegraph, Malcolm Moore, 14 June 2007

- Guggenheimer, Heinrich W. (1 August 2013). The Jerusalem Talmud. Second order, Mo'ed. Tractates Pesaḥim and Yoma = [Talmud Yerushalmi]. [Seder Mo'ed], [Masekhtot Pesaḥim ṿe- Yoma]. Guggenheimer, Heinrich W. (Heinrich Walter), 1924–. Berlin. ISBN 9783110315981. OCLC 868971291.

- Pilgrimage in Graeco-Roman & early Christian antiquity : seeing the gods. Elsner, Jaś., Rutherford, Ian, 1959–. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2005. ISBN 978-0199250790. OCLC 191935422.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Ascough, Richard S. (2007-05-17). "Pilgrimage in Graeco-Roman and Early Christian Antiquity: Seeing the Gods. Edited by Jaś Elsner and Ian Rutherford". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 75 (2): 418–421. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfm007. ISSN 1477-4585

- "Dio Cassius (Cassius Dio Coccianus) (c.163/4 – c.235 ce)", Ancient Historians : A Student Handbook, Continuum, ISBN 9781472540607, retrieved 2018-12-11

- Adler, M. N. (April 1905). "The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela (Continued)". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 17 (3): 514–530. doi:10.2307/1450981. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1450981.

- "Descriptive Gazetteer entry for Canterbury". Vision of Britain. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- "The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer". British Library.

- Godfrey-Faussett 1878, p. 29.

- Lyle 2002, pp. 97–100.

- Quoted in Robin Lane Fox, The Unauthorized Version, 1992:235.

- General context of early Christian pilgrimage is provided by E.D. Hunt, Holy Land Pilgrimage in the Late Roman Empire AD 312–460 1982.

- Wickham Inheritance of Rome p. 280

- Pringle "Architecture in Latin East" Oxford History of the Crusades p. 157

- Long, Edward LeRoy (2014). The Nature and Future of Christianity: A Study of Alternative Approaches. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781630872533.

Taizé was founded in 1940 by a Protestant, Roger Schutz, who has authored several books on the contemplative life and its relationship to social outreach. Over a hundred thousand pilgrims, mostly young people, make pilgrimages to Taizé community every year, where they engage for various lengths of time in Bible study, sharing, and communal work.

- Rosauer, Ruthie; Hill, Liz (2010). Singing Meditation: Together in Sound and Silence. Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations. ISBN 9781558965843.

Taizé music has now become a focal point of popular Taizé-style services held regularly in many denominations, including Roman Catholic, Methodist, Episcopal, Presbyterian, and Lutheran.

- Fletcher, R. A. (1984). Saint James's catapult : the life and times of Diego Gelmírez of Santiago de Compostela. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822581-2.

- Fletcher, R. A. (1984). Saint James's catapult: the life and times of Diego Gelmírez of Santiago de Compostela. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Clarendon Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-19-822581-2.

- Collins, Roger (1983). Early Medieval Spain. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-312-22464-6.

- Portela Silva, Ermelindo (2001). García II de Galicia, el rey y el reino (1065–1090). Burgos: La Olmeda. p. 165. ISBN 978-84-89915-16-9.

- Fletcher, R. A. (1984). Saint James's catapult : the life and times of Diego Gelmírez of Santiago de Compostela. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Clarendon Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-19-822581-2.

- A.M. Koldeweij (1990): 'Pelgrimages'. In: Th.J. van Rensch, A.M. Koldeweij, R.M. de la Haye, M.L. de Kreek (1990): Hemelse trektochten. Broederschappen in Maastricht 1400–1850, pp. 107–113. Vierkant Maastricht #16. Stichting Historische Reeks Maastricht, Maastricht. ISBN 90-70356-55-4.

- 'Maastricht, H. Servaas (Servatius)' on website meertens.knaw.nl

- 'Mehr Pilger als erwartet kamen nach Aachen', in: Die Welt 30 June 2014.

- "Popular Catholic Shrines". Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- "Religion moves 330 million tourists a year and six million go to Fátima", Diário de Notícias, 19 February 2017.

- "Fátima expects to receive 8 million visitors in 2017", in Sapo20, 15 December 2016.

- "Rosarium Virginis Mariae on the Most Holy Rosary (October 16, 2002) – John Paul II". w2.vatican.va.

- "Lourdes – The Skeptic's Dictionary". Skepdic.com. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- N. Ross Crumrine and E. Alan Morinis, Pilgrimage in Latin America. Westport CT 1991.

- Thomas S. Bremer, "Pilgrimage," in Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures, David Carrasco, ed. Vol. 3, pp. 1–3. New York: Oxford University Press 2001.

- George A. Kubler. "Pre-Columbian Pilgrimages in Mesoamerica," In Fourth Palenque round Table, edited by Elizabeth P. Benson, 313-16. San Francisco 1985.

- Stafford Poole. Our Lady of Guadalupe: The Origins and Sources of a Mexican National Symbol, 1531–1797. Tucson: University of Arizona Press 1995.

- "The Pope meets clergy in the shrine of El Quinche and bids farewell to Ecuador," Gaudium Press, http://en.gaudiumpress.org/content/71388-The-Pope-meets-clergy-in-the-shrine-of-El-Quinche-and-bids-farewell-to-Ecuador-, accessed 3 June 2017

- http://en.gaudiumpress.org/content/71388-The-Pope-meets-clergy-in-the-shrine-of-El-Quinche-and-bids-farewell-to-Ecuador-, accessed 3 June 2017

- "Official website of the National Shrine of Our Lady of El Cisne". Archived from the original on 25 August 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- https://sacredsites.com/americas/ecuador/el_cisne.html

- Kris E. Lane, "Review: Carolyn Dean, Inka Bodies and the Body of Christ: Corpus Christi in Colonial Cuzco, Peru ", Ethnohistory, Volume 48, Number 3, Summer 2001, pp. 544–546; accessed 22 December 2016

- Sallnow, Pilgrims of the Andes, p. 226.

- Randall, "Quyllurit'i", p. 44.

- McCarl, Clayton. "An Indigenous Sculptor on the Spanish Stage: Calderón's rewriting of Tito Yupanqui in La Aurora en Copacabana". cuny.edu. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

Sources

- Lyle, Marjorie (2002), Canterbury: 2000 Years of History, Tempus, ISBN 978-0-7524-1948-0

External links

- Database of Shrines and Pilgrimage in the Netherlands

- Galilean Destinations for Christians

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.