Decapolis

The Decapolis (Greek: Δεκάπολις Dekápolis, Ten Cities) was a group of ten cities on the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire in the southeastern Levant in the first centuries BC and AD. They formed a group because of their language, culture, location, and political status, with each functioning as an autonomous city-state dependent on Rome. They are sometimes described as a league of cities, although some scholars believe that they were never formally organized as a political unit.

Decapolis Δεκάπολις | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 63 BC–AD 106 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Common languages | Koine Greek, Aramaic, Arabic, Latin, Hebrew | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Imperial cult (ancient Rome) | ||||||||||||

| Government | Client state | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Pompey's conquest of Syria | 63 BC | ||||||||||||

• Trajan's annexation of Arabia Petrea | AD 106 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

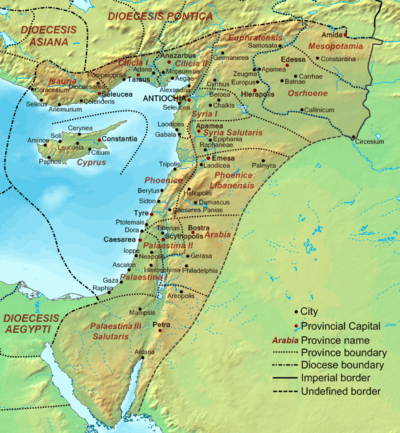

The Decapolis was a center of Greek and Roman culture in a region which was otherwise populated by Semitic-speaking people (Nabataeans, Arameans, and Judeans). In the time of the Emperor Trajan, the cities were placed into the provinces of Syria and Arabia Petraea; several cities were later placed in Syria Palaestina and Palaestina Secunda. Most of the Decapolis region is located in Jordan, but Damascus is in Syria and Hippos and Scythopolis are in the Golan Heights and Israel, respectively.

Cities

The names of the traditional Ten Cities of the Decapolis come from Pliny's Natural History.[1] They are:

- Gerasa (Jerash) in Jordan

- Scythopolis (Beit She'an) in Israel, the only city west of the Jordan River

- Hippos (also Hippus or Sussita; Al-Husn in Arabic) on the Golan Heights

- Gadara (Umm Qais) in Jordan

- Pella (west of Irbid) in Jordan

- Philadelphia, modern day Amman, the capital of Jordan

- Capitolias, also Dion, probably Beit Ras or possibly Al Husn, less likely Aydoun, all in Jordan

- Canatha (Qanawat) in Syria

- Raphana, usually identified with Abila in Jordan

- Damascus, the capital of modern Syria[2]

Damascus was further north than the others and so is sometimes thought to have been an "honorary" member. Josephus stated that Scythopolis was the largest of the ten towns.[3] Biblical commentator Edward Plumptre therefore suggested that Damascus was not included in Josephus' list.[4] According to other sources, there may have been as many as eighteen or nineteen Greco-Roman cities counted as part of the Decapolis.

History

Hellenistic era

Except for Damascus, the Decapolis cities were by and large founded during the Hellenistic period, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the Roman conquest of Coele-Syria, including Judea in 63 BC. Some were established under the Ptolemaic dynasty which ruled Judea until 198 BC. Others were founded later, when the Seleucid dynasty ruled the region. Some of the cities included "Antiochia" or "Seleucia" in their official names (Antiochia Hippos, for example), which attest to Seleucid origins. The cities were Greek from their founding, modeling themselves on the Greek polis.

The Decapolis was a region where two cultures interacted: the culture of the Greek colonists and the indigenous Semitic culture. There was some conflict. The Greek inhabitants were shocked by the Semitic practice of circumcision, while various elements of Semitic dissent towards the dominant and assimilative nature of Hellenic civilization arose gradually in the face of assimilation.

At the same time, cultural blending and borrowing also occurred in the Decapolis region. The cities acted as centers for the diffusion of Greek culture. Some local deities began to be called by the name Zeus, from the chief Greek god. Meanwhile, in some cities Greeks began worshipping these local "Zeus" deities alongside their own Zeus Olympios. There is evidence that the colonists adopted the worship of other Semitic gods, including Phoenician deities and the chief Nabatean god, Dushara (worshipped under his Hellenized name, Dusares). The worship of these Semitic gods is attested to in coins and inscriptions from the cities.

The Roman general Pompey conquered the eastern Mediterranean in 63 BC. The people of the Hellenized cities welcomed Pompey as a liberator from the Jewish Hasmonean kingdom that had ruled much of the area. When Pompey reorganized the region, he awarded a group of these cities with autonomy under Roman protection. This was the origin of the Decapolis. For centuries the cities based their calendar era on this conquest: 63 BC was the epochal year of the Pompeian era, used to count the years throughout the Roman and Byzantine periods.

Autonomy under Rome

Under Roman rule, the cities of the Decapolis were not included in the territory of the Herodian kingdom, its successor states of the Herodian tetrarchy, or the Roman province of Judea. Instead, the cities were allowed considerable political autonomy under Roman protection. Each city functioned as a polis or city-state, with jurisdiction over an area of the surrounding countryside. Each minted its own coins. Many coins from Decapolis cities identify their city as "autonomous," "free," "sovereign," or "sacred," terms that imply some sort of self-governing status.[5]

The Romans left their cultural stamp on all of the cities. Each one was eventually rebuilt with a Roman-style grid of streets based around a central cardo and/or decumanus. The Romans sponsored and built numerous temples and other public buildings. The imperial cult, the worship of the Roman emperor, was a very common practice throughout the Decapolis and was one of the features that linked the different cities. A small open-air temple or façade, called a kalybe, was unique to the region.[6]

The cities may also have enjoyed strong commercial ties, fostered by a network of new Roman roads. This has led to their common identification today as a "federation" or "league". The Decapolis was probably never an official political or economic union; most likely it signified the collection of city-states which enjoyed special autonomy during early Roman rule.[7][8]

The New Testament gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke mention that the Decapolis region was a location of the ministry of Jesus. According to Matthew 4:23-25 the Decapolis was one of the areas from which Jesus drew his multitude of disciples, attracted by His "healing all kinds of sickness". The Decapolis was one of the few regions where Jesus travelled in which Gentiles were in the majority: most of Jesus' ministry focused on teaching to Jews. Mark 5:1-10 emphasizes the Decapolis' gentile character when Jesus encounters a herd of pigs, an animal forbidden by Kashrut, the Jewish dietary laws. A demon-possessed man healed by Jesus in this passage asked to be included among the disciples who traveled with Jesus; but he was refused, and instructed to remain in the Decapolis region.[9]

Direct Roman rule

The Decapolis came under direct Roman rule in AD 106, when Arabia Petraea was annexed during the reign of the emperor Trajan. The cities were divided between the new province and the provinces of Syria and Judea.[5] In the later Roman Empire, they were divided between Arabia and Palaestina Secunda, of which Scythopolis served as the provincial capital; while Damascus became part of Phoenice Libanensis. The cities continued to be distinct from their neighbors within their provinces, distinguished for example by their use of the Pompeian calendar era and their continuing Hellenistic identities. However, the Decapolis was no longer a unit of administration.

The Roman and Byzantine Decapolis region was influenced and gradually taken over by Christianity. Some cities were more receptive than others to the new religion. Pella was a base for some of the earliest church leaders (Eusebius reports that the apostles fled there to escape the First Jewish–Roman War). In other cities, paganism persisted long into the Byzantine era. Eventually, however, the region became almost entirely Christian, and most of the cities served as seats of bishops.

Most of the cities continued into the late Roman and Byzantine periods. Some were abandoned in the years following Palestine's conquest by the Umayyad Caliphate in 641, but other cities continued to be inhabited long into the Islamic period.

Evolution and excavation

Jerash (Gerasa) and Bet She'an (Scythopolis) survive as towns today, after periods of abandonement or serious decline. Damascus has never lost its prominent role throughout later history. Philadelphia was long abandoned, but was revived in the 19th century and has become the capital city of Jordan under the name Amman. Twentieth-century archaeology has identified most of the other cities on Pliny's list, and most have undergone or are undergoing considerable excavation.[10][11][12][13][14]

See also

- Heptapolis (meaning seven cities)

- Doric hexapolis (six)

- Pentapolis (five)

- Tetrapolis (four)

- Tripolis (three)

References

- Natural History, 5.16.74

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online Edition "Decapolis - Ancient Greek League, Palestine" https://www.britannica.com/place/Decapolis-ancient-cities-Palestine

- Wars of the Jews, Book 3, chapter 9, section 7, accessed 6 December 2016

- Plumptre, E. H., in Ellicott's Commentary for English Readers on Matthew 4, accessed 6 December 2016

- Mare, Harold W. (2000). "Decapolis". In Freedman, David Noel (ed.). Eerdman's Dictionary of the Bible. William B. Eerdman's Publishing Company. pp. 333–334. ISBN 0-8028-2400-5.

- Segal, Arthur (2001). "The "Kalybe Structures" : Temples for the Imperial Cult in Hauran and Trachon: An Historical-architectural Analysis". Assaph: Studies in Art History. Tel Aviv University. 6: 91–118.

- "Decapolis" in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East. Ed. Eric M. Meyers, S. Thomas Parker. Oxford Biblical Studies Online. Nov 14, 2016.

- "oxfordbiblicalcstudies.com". ww1.oxfordbiblicalcstudies.com. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- Mark 5:18-20

- Segal, Arthur. "The 'Kalybe' Structures." Zinman Institute of Archaeology, Haifa University.

- Parker, S. Thomas (September 1999). "An Empire's New Holy Land: The Byzantine Period". Near Eastern Archaeology. 62 (3): 134–180. doi:10.2307/3210712. ISSN 1094-2076. JSTOR 3210712.

- Meyers, Eric M. (December 1996). "The Making of the Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East". The Biblical Archaeologist. 59 (4): 194–197. doi:10.2307/3210561. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3210561.

- Collins, Adela Yarbro (August 1996). "The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Ephraim Stern , Ayelet Lewinson-Gilboa , Joseph Aviram". History of Religions. 36 (1): 81–83. doi:10.1086/463453. ISSN 0018-2710.

- Chancey, Mark Alan; Porter, Adam Lowry (December 2001). "The Archaeology of Roman Palestine". Near Eastern Archaeology. 64 (4): 164–203. doi:10.2307/3210829. ISSN 1094-2076. JSTOR 3210829.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Decapolis. |

- The Decapolis on BibArch

- The Decapolis on the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Scholarly review of a 2003 book, Kulte und Kultur der Dekapolis (Cults and Culture of the Decapolis). The review contains information on the religious syncretism in the Hellenistic and Roman Decapolis. Contains some passages in German.