Stewart Island

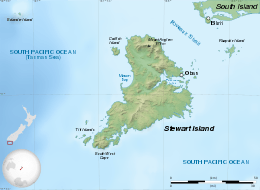

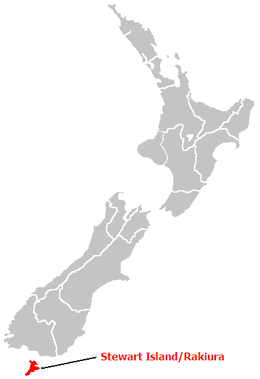

Stewart Island / Rakiura, commonly known as Stewart Island, is New Zealand's third-largest island, located 30 kilometres (19 miles) south of the South Island, across the Foveaux Strait. It is a roughly triangular island with a total land area of 1,746 square kilometres (674 sq mi). Its 164 kilometres (102 mi) coastline is deeply creased by Paterson Inlet (east), Port Pegasus (south), and Mason Bay (west). The island is generally hilly (rising to 980 metres [3,220 ft] at Mount Anglem) and densely forested. Flightless birds, including penguins, thrive because there are few introduced predators.

| Native name: | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Foveaux Strait |

| Coordinates | 47°00′S 167°50′E |

| Archipelago | New Zealand archipelago |

| Area | 1,746 km2 (674 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 980 m (3,220 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Anglem |

| Administration | |

| Regional Council | Southland |

| Largest settlement | Oban |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 408[1] (2018) |

| Pop. density | 0.2/km2 (0.5/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Pākehā (80%), Māori (20%) |

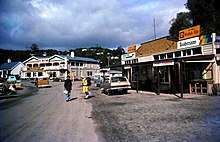

Stewart Island/Rakiura is sparsely populated and its economy is dependent on summer tourism and fishing. Its permanent population was recorded at 408 people as of the 2018 census,[1] most of whom live in the settlement of Oban on the eastern side of the island. Ferries connect the settlement to Bluff in the South Island. Stewart Island/Rakiura is part of the Southland District for local government purposes.

History and naming

The original Māori name, Te Punga o Te Waka a Māui, positions Stewart Island firmly at the heart of Māori mythology. Translated as The Anchor Stone of Māui’s Canoe, it refers to the part played by the island in the legend of Māui and his crew, who from their canoe, the South Island, caught and raised the great fish, the North Island.

Rakiura is the more commonly known and used Māori name. It is usually translated as Glowing Skies, possibly a reference to the sunsets for which it is famous or for the aurora australis, the southern lights that are a phenomenon of southern latitudes.

For some, Rakiura is the abbreviated version of Te Rakiura a Te Rakitamau, translated as "great blush of Rakitamau", in reference to the latter's embarrassment when refused the hand in marriage of not one, but two daughters, of an island chief.[2] According to Māori legend, a chief on the island named Te Rakitamau was married to a young woman who became terminally ill and implored him to marry her cousin after she died. Te Rakitamau paddled across Te Moana Tapokopoko a Tawhiki (Foveaux Strait) to the South Island where the cousin lived, only to discover she had recently married. He blushed with embarrassment; so the island was called Te Ura o Te Rakitamau.

Captain James Cook and his crew were the first Europeans to sight the island from the Endeavour in March 1770. As the ship sailed south around it, Cook recorded its insularity and described the strait that separates it from the South Island. It is argued by Margaret Cameron-Ash that he decided to hide it. She points out that he was operating during the period of intense Anglo-French rivalry that filled the twelve years between Britain's success in the Seven Years' War and France's revanche in the American Revolutionary War.[3] According to Cameron-Ash, he recalled the Admiralty's verbal instructions to conceal strategically important discoveries that could become security risks, such as off-shore islands from which operations could be mounted by a hostile power. Cook knew he had to hide Foveaux Strait and depict Stewart Island as a peninsula. Consequently, he altered his journal entry and redrew his chart of New Zealand showing the two southerly islands joined by an isthmus.[4]

The strait was first charted by Owen Folger Smith, a New Yorker who had been in Sydney Harbour with Eber Bunker from whom he probably learned of the eastern seal fishery. Smith charted the strait in the whaleboat of the sealing brig Union (out of New York) in 1804 and on his 1806 chart it was called Smith's Straits.[5]

The island received its English name in honour of William W. Stewart. He was first officer on the Pegasus which visited in 1809 and he charted the large south-eastern harbour that now bears the ship's name (Port Pegasus), and determined the northern points of the island, proving that it was an island.[6][7] In 1824 he initiated plans in England to establish a timber, flax and trading settlement at Stewart Island and sailed there in 1826,[6] with it becoming known as Stewart's Island.

In 1841, the island was established as one of the three Provinces of New Zealand, and was named New Leinster. However, the province existed on paper only and was abolished after only five years. With the passing of the New Zealand Constitution Act 1846, the province became part of New Munster, which entirely included the South Island.[8] When New Munster was abolished in 1853, Stewart Island became part of Otago Province until 1861, when Southland Province split from Otago. In 1876, the provinces were abolished altogether.

For most of the twentieth century, "Stewart Island" was the official name, and that is still in common use by most New Zealanders. The name was officially altered to Stewart Island/Rakiura by the Ngai Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998, one of many such changes under the Ngāi Tahu treaty settlement.[9]

Geography

Stewart Island has an area of 1,680 square kilometres (650 sq mi).[10] Its terrain is hilly and, like most of New Zealand, Stewart Island has an Oceanic climate. The north is dominated by the swampy valley of the Freshwater River. The river rises close to the northwestern coast and flows southeastwards into the large indentation of Paterson Inlet. The highest peak is Mount Anglem (980 metres (3,220 ft)), close to the northern coast. It is one of a rim of ridges that surround Freshwater Valley.

The southern half is more uniformly undulating, rising to a ridge that runs south from the valley of the Rakeahua River, which also flows into Paterson Inlet. The southernmost point in this ridge is Mount Allen, at 750 metres (2,460 ft). In the southeast the land is somewhat lower, and is drained by the valleys of the Toitoi River, Lords River, and Heron River. South West Cape on this island is the southernmost point of the main islands of New Zealand.

Mason Bay, on the west side, is notable as a long sandy beach on an island where beaches are typically far more rugged. One suggestion is that the bay was formed in the aftershock of a meteorite impact in the Tasman Sea; however, no evidence has been found to support such a claim.[11][12]

Three large and many small islands lie around the coast. Notable among these are Ruapuke Island, in Foveaux Strait 32 kilometres (20 mi) northeast of Oban; Codfish Island, close to the northwest shore; and Big South Cape Island, off the southwestern tip. The Titi/Muttonbird Islands group is between Stewart Island and Ruapuke Island, around Big South Cape Island, and off the southeastern coast. Other islands of interest include Bench Island, Native Island, and Ulva Island, all close to the mouth of Paterson Inlet, and Pearl Island, Anchorage Island, and Noble Island, close to Port Pegasus in the southwest. Further offshore The Snares are oceanic islands, a volcano and some smaller islets, that were never connected to the larger Stewart Island.

Stewart Island has a temperate climate.[13] However, one travel guide mentions "frequent downpours that make 'boots and waterproof clothing mandatory",[14] and another guide says that rainfall in Oban, the principal settlement, is 1,600 to 1,800 mm (63 to 71 in) a year.[15]

Owing to an anomaly in the magnetic latitude contours, this location is well placed for observing Aurora australis.

Settlements

The only town is Oban, on Halfmoon Bay.

A previous settlement, Port Pegasus, once boasted several stores and a post office, and was located on the southern coast of the island. It is now uninhabited, and is accessible only by boat or by an arduous hike through the island. Another site of former settlement is at Port William, a four-hour walk around the north coast from Oban, where immigrants from the Shetland Islands settled in the early 1870s. This was unsuccessful, and the settlers left within one to two years, most for sawmilling villages elsewhere on the island.

Since 1988 the electricity supply on Stewart Island has come from diesel generators; previously residents used their own private generators. As a consequence electric power is around three times more expensive than in the South Island, at NZ$0.59/kWh in 2016.[16] After photovoltaic and wind generation were tested on the island,[16] the government providential growth fund put $3.16 million dollars towards building wind turbines on Stewart Island [17]

Economy and communications

Fishing has been, historically, the most important element of the economy of Stewart Island, and while it remains important, tourism has become the main source of income for islanders. There has also been some farming and forestry. Oban has mainly sealed main roads, and some gravel roads on the outskirts.

Stewart Island Flights links Ryan's Creek Aerodrome and Invercargill Airport and aircraft also land on the sand at Mason Bay, Doughboy Bay, and West Ruggedy Beach. A regular passenger ferry service runs between Bluff and Oban. The only ferry/barge link to the South Island for vehicles is to Bluff.

Oban has phone and broadband (ADSL) services. Cellphone coverage is provided by Spark and Vodafone. All these services rely on a radio link to Bluff, so broadband speeds are limited.

Stewart Island is able to receive most AM and FM radio stations broadcast in the Southland region. Television services are available via satellite using Sky or Freeview. Analogue terrestrial television services could be received on Stewart Island from the Hedgehope television transmitter located in the South Island prior to the analogue switch off on April 28, 2013.

Government

From 1841 to 1853, Stewart Island was governed as New Leinster Province, then as part of New Munster Province. From 1853 onwards, it was part of the Otago Province. In local government today, Stewart Island is part of the Southland District and the Southland Region. However, it shares with some other islands a certain relaxation in some of the rules governing commercial activities. For example, every transport service operated solely on Great Barrier Island, the Chatham Islands, or Stewart Island is exempt from the Transport Act of 1962.

Ecology

Flora

Although the clay soil is not very fertile, the high rainfall and warm weather mean that the island is densely forested throughout. Native plants include the world's southernmost dense forest of podocarps (southern conifers) and hardwoods such as rātā and kāmahi in the lowland areas with mānuka shrubland at higher elevations. The trees are thought to have become established here since the last ice age from seeds brought across the strait by seabirds, which would explain why the beech trees that are so common in New Zealand, but whose seeds are dispersed by the wind rather than birds, are not found on Stewart Island.

Noeline Baker purchased land near Halfmoon Bay in the early 1930s, and with a checklist by botanist Leonard Cockayne populated it with all the local indigenous plants. She gifted the land and her house to the government in 1940, and today Moturau Moana is New Zealand's southernmost public garden.[18]

Fauna

There are many species of birds on Stewart Island that have been able to continue to thrive because of the relative absence of the cats, rats, stoats, ferrets, weasels and other predators that humans brought to the main islands. There are even more species of birds, including huge colonies of sooty shearwater and other seabirds, on The Snares and the other smaller islands offshore. The birds of Stewart Island include weka, kākā, albatross, the flightless Stewart Island kiwi, silvereyes, fantails, and kererū. The endangered yellow-eyed penguin has a significant number of breeding sites here [19] while the large colonies of sooty shearwaters on the offshore Muttonbird Islands, are subject to muttonbirding, a sustainable harvesting program managed by Rakiura Māori. Meanwhile, a small population of the kakapo, a flightless parrot which is very close to extinction, was found on Stewart Island in 1977 and the birds subsequently moved to smaller islands (Codfish Island) for protection from feral cats. The South Island saddleback is similarly preserved.

Threats and preservation

As the island has always been sparsely populated and there has never been very much logging, much of the original wildlife is intact, including species that have been devastated on the larger islands to the north since their habitation by humans. However, although habitats and wildlife were not threatened by invasive species historically, now there are populations of cats, rats and brushtail possums on the island, as well as a large population of white-tailed deer, which are hunted for meat and sport, introduced to coastal areas. There is also a small population of red deer confined to the inland areas.[20] Almost all the island is owned by the New Zealand government and over 80 per cent of the island is set aside as the Rakiura National Park, New Zealand's newest national park. Many of the small offshore islands, including the Snares, are also protected.

Claims of independence

Residents of Stewart Island have held a number of mock promotional fundraising events regarding a declaration of independence for the island, and to have it renamed to its original name of "Rakiura".

In the late 1950s or early 1960s, they had a local printer overprint “INDEPENDENT RAKIURA” on eight values of some earlier New Zealand postage and health stamps. Eight different values, from one penny to £1, were overprinted on the stamps, and their original values were blotted out with small black circles. The stamps were sold to collectors, with the proceeds helping to refurbish the Rakiura Museum.

An effort to raise NZ$6,000 for a new swimming pool at the island's school involved selling 50-cent passports for the newly "independent" island. On 31 July 1970, a mock ceremony featured a declaration of independence, and the new republic's flag was unveiled.

These efforts were not serious attempts for independence, and Stewart Island remains a part of the New Zealand state.[21]

References

- "2018 Census place summaries". www.stats.govt.nz. Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "Features: Rakiura National Park". Department of Conservation (New Zealand). Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- Cameron-Ash, M. (2018). Lying for the Admiralty: Captain Cook's Endeavour Voyage. Rosenberg. p. 80-93. ISBN 9780648043966.

- Cameron-Ash, M. (2018). Lying for the Admiralty. Sydney: Rosenberg. pp. 141–145. ISBN 9780648043966.; But see also G.A. Mawer, review of Lying for the Admiralty: Captain Cook's Endeavour Voyage, The Globe, No. 84, 2018, pp.59-61; Nigel Erskine, “James Cook's False Trail: Hidden Discoveries, Altered Records”, Signals, No. 125, Dec 2018-Feb 2019 pp.72-73. Both these authors argue against Cameron-Ash's contention.

- Howard, Basil, and Stewart Island Centennial Committee. Rakiura: a History of Stewart Island, New Zealand, Basil Howard Reed for the Stewart Island Centennial Committee, Dunedin, 1940, p.22; Charles A. Begg and Neil C. Begg, Port Preservation, Christchurch, Whitcombe & Tombs, 1973, p.61; Peter Entwisle, Behold the Moon: The European Occupation of the Dunedin District 1770-1848, Dunedin, Port Daniel Press, 1998.

- Foster, Bernard John (1966). "Stewart, Captain William W.". In McLintock, Alexander (ed.). An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 19 May 2019 – via Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- John O'C. Ross, William Stewart, Sealing Captain, Trader and Speculator, Aranda (A.C.T), Roebuck Society, 1987, pp. 97-117.

- Paterson, Donald Edgar (1966). "New Leinster, New Munster, and New Ulster". In McLintock, Alexander (ed.). An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 18 May 2019 – via Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- Schedule 96 Alteration of place names

- Walrond, Carl (3 September 2012). "Stewart Island/Rakiura – New Zealand's third main island". Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- Collins, Simon (6 February 2004). "Expedition hunts giant meteor". NZ Herald. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Goff J, Dominey-Howes D, Chagué C, Courtney C (2010). "Analysis of the Mahuika comet impact tsunami hypothesis". Marine Geology. 271 (3): 292–296. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2010.02.020. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- "weather". Stewart Island. Stewart Island Promotion Association Inc. 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- "Weather in Stewart Island". When to go & weather. Lonely Planet. 2012. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- "Weather". Wilderness Experience. Raggedy Range. 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- "Stewart Is may lead NZ in green power". 26 April 2008. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010.

- "Provincial Growth Fund bankrolls two wind turbines for Stewart Island". Stuff. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Taylor, Leah. "Isabel Noeline Baker". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- C. Michael Hogan. 2009. Yellow-eyed Penguin: Megadypes antipodes, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. Stromberg

- "Rakiura Island temperate forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Stewart Island (New Zealand)

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Stewart Island. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stewart Island. |