Spriggan

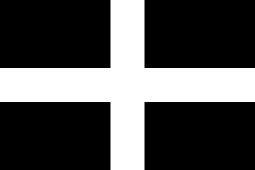

A spriggan /sprɪdʒən/ is a legendary creature from Cornish faery lore. Spriggans are particularly associated with West Penwith in Cornwall.[1]

Sculpture by Marilyn Collins | |

| Grouping | Mythological creature Fairy Sprite |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Region | Cornwall |

Spriggan is a dialect word, pronounced with the grapheme <gg> as /d͡ʒ/, sprid-jan, and not sprigg-an, borrowed from the Cornish plural spyrysyon 'spirits'.[2]

In folklore

"The Spriggans are found only about the cairns, coits, or cromlechs, burrows, or detached stones, with which it is unlucky for mortals to meddle. A correspondent writes: "This is known, that they were a remarkably mischievous and thievish tribe. If ever a house was robbed, a child kidnapped, cattle carried away, or a building demolished, it was the work of the Spriggans. Whatever commotion took place in earth, air, or water, it was all put down as the work of these spirits. Wherever the giants have been, there the Spriggans have been also. It is usually considered that they are the ghosts of the giants; certainly, from many of their feats, we must suppose them to possess a giant's strength. The Spriggans have the charge of buried treasure.[3]

According to The English Dialect Dictionary (1905), spriggans were apparently related to the trolls of Scandinavia.[4] Spriggans were depicted as grotesquely ugly, wizened old men with large childlike heads. They were said to be found at old ruins, cairns, and barrows guarding buried treasure.[5] Although small, they were usually considered to be the ghosts of giants,[4] with the ability to swell to enormous size. They were also said to act as fairy bodyguards.

Spriggans were notorious for their unpleasant dispositions, and delighted in working mischief against those who offended them. They raised sudden whirlwinds to terrify travellers, sent storms to blight crops, and sometimes stole away mortal children, leaving their ugly changelings in their place.[5] They were blamed if a house was robbed or a building collapsed, or if cattle were stolen.[4] In one story, an old woman got the better of a band of spriggans by turning her clothing inside-out (turning clothing supposedly being as effective as holy water or iron in repelling fairies) to gain their loot.[6] It was not spriggans but the buccas or knockers who were associated with tin mining, acting as guardians to the workings, and apart from the mischievous nature above, their attitude to miners seems to have been one of protection.[7] However it is said that "On Christmas-eve, in former days, the small people, or the spriggans, would meet at the bottom of the deepest mines, and have a midnight mass."[8]

Sculpture

A sculpture of a spriggan by Marilyn Collins can be seen in Crouch End, London, in some arches lining a section of the Parkland Walk (a disused railway line). If walking along the Parkland Walk from Finsbury Park to Highgate station the Spriggan is to the right just before the disused railway platforms of the former Crouch End station. To the left, on the southside of the Parkland Walk is Crouch Hill Park where Ashmount School has been located since January 2013. The sculpture is sometimes mistaken for the Green Man or Pan.

References

- Various folklore collections e.g. Craig Weatherhill and Paul Devereux, Myths and Legends of Cornwall, 1994, p.23, Sigma Leisure, ISBN 978-1850583172

- Dr Ken George, An Gerlyver Meur, p. 600, Cornish Language Board, ISBN 978-1902917849

- Robert Hunt, Popular Romances of the West of England, 3rd edition, 1916, p. 81, ISBN 978-1605064604

- Wright, Joseph, ed. (1905). The English Dialect Dictionary. V. Henry Frowde. p. 690.

- Piskies, Spriggans, Knockers, and the Small People – Traditional Tales from Cornwall. Truro: Tor Mark Press. c. 1979. p. 2. ISBN 978-0850250435.

- Robert Hunt, Popular Romances of the West of England, 3rd edition, 1916, The Old Woman Who Turned Her Shift, page 113-114

- Robert Hunt, Popular Romances of the West of England, 3rd edition, 1916, page 82

- Robert Hunt, Popular Romances of the West of England, 3rd edition 1916, page 349

Sources

- Briggs, Katharine. A Dictionary of Fairies. Penguin, 1976, ISBN 978-0140176582

- Underground History: The Northern Heights, Hywel Williams. Accessed 8 July 2007.