Kinnara

In Hindu mythology, a kinnara is a paradigmatic lover, a celestial musician, part human, part horse and part bird. In Buddhist mythology, two of the most beloved mythological characters are the benevolent half-human, half-bird creatures known as the Kinnara and Kinnari, which are believed to come from the Himalayas and often watch over the well-being of humans in times of trouble or danger. Their character is clarified in the Adi Parva of the Mahabharata, where they say:

We are everlasting lover and beloved. We never separate. We are eternally husband and wife; never do we become mother and father. No offspring is seen in our lap. We are lover and beloved ever-embracing. In between us we do not permit any third creature demanding affection. Our life is a life of perpetual pleasures.[1]

- For the social group or caste amongst the Sinhalese of Sri Lanka, see Kinnaraya

They are also featured in a number of Buddhist texts, including the Lotus Sutra. An ancient Indian string instrument is known as the Kinnari Veena.

In Southeast Asian mythology, Kinnaris, the female counterpart of Kinnaras, are depicted as half-bird, half-woman creatures. One of the many creatures that inhabit the mythical Himavanta, Kinnaris have the head, torso, and arms of a woman and the wings, tail and feet of a swan. They are renowned for their dance, song and poetry, and are a traditional symbol of feminine beauty, grace and accomplishment.

Edward H. Schafer notes that in East Asian religious art the Kinnara is often confused with the Kalaviṅka, which is also a half-human half-bird hybrid mythical creature, but that the two are actually distinct and unrelated.[2]

Burma

In Burma (Myanmar), kinnara are called keinnaya or kinnaya (ကိန္နရာ [kèɪɰ̃nəjà]). Female kinnara are called keinnayi or kinnayi (ကိန္နရီ [kèɪɰ̃nəjì]). In Shan, they are ၵိင်ႇၼရႃႇ (Shan pronunciation: [kìŋ nǎ ràː]) and ၵိင်ႇၼရီႇ (Shan pronunciation: [kìŋ nǎ rì]) respectively. Burmese Buddhists believe that out of the 136 past animal lives of Buddha, four were kinnara. The kinnari is also one of the 108 symbols on the footprint of Buddha.

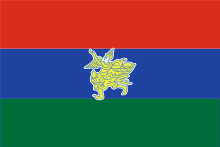

In Burmese art, kinnari are depicted with covered breasts. The Myanmar Academy Awards statue for Academy Award winners is of a kinnari.[3] The kinnara and kinnari couple is considered the symbol of the Karenni people.[4]

Cambodia

In Cambodia, the kinnaras are known in the Khmer language as kenar (កិន្នរ, កិន្នរា; IPA: [keˈnɑː] or IPA: [ken nɑ ˈraː]). The female counterpart, the kinnari (កិន្នរី; IPA: [ken nɑ ˈrəj]), are depicted in Cambodian art and literature more often than the male counterparts. They are commonly seen carved into support figurines for the columns of post-Angkorian architecture. Kinnari are considered symbols of beauty and are skilled dancers.[5]

The Kenorei is a character archetype in the repertoire of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia, appearing as mischievous groups that have a strong allurement. A classical dance titled Robam Kenorei depicts kinnaris playing in a lotus pond.

India

In the Sanskrit language, the name Kinnara contains a question mark (Sanskrit : किन्नर?) i.e. is this man?. In Hindu mythology, Kinnara is described as half-man, half-horse, and half-bird. The Vishnudharmottara describes Kinnara as half-man and half-horse, but the correct nature of Kinnara as Buddhists understood is half-man and half-bird. The figure of Yaksha with a horse head illustrated in Bodh Gaya sculptures in however a Kinnari as the Jataka illustrating it treats her as a demi-god. According to the Jatakas, Kinnaras are fairies and are shown as going in pairs noted for mutual love and devotion. In the Chanda Kinnara Jataka the devotion of the Kinnarai to her wounded Kinnara husband brings Indra on the scene to cure him from the wound. The Kinnaras are noted for their long life.[6]

The Jatakas describe the Kinnaras as innocent and harmless, hop like birds, are fond of music and song, and with the female beating a drum and male playing on lute. Such harmless creatures are described in Jataka No.481 as being caught, put into cages, and thus presented to kings for their delight. In Jataka No.504, we have the autobiography of a Kinnara who describes the Kinnara class as human-like the wild things deem us; huntsmen call us goblins still. The Kinnaras can sing, play the flute and dance with soft movements of the body. Kalidasa in his Kumara Sambhava describes them as dwelling in the Himalayas. Kinnaras lived also over the hills of Pandaraka, Trikutaka, Mallangiri, Candapabbata, and Gandhamandana (Jataka No. 485). They were tender-hearted and Jataka No. 540 refers to the story of the Kinnaras nursing a human baby whose parents have gone away to the woods. Yet, we find that they were looked upon as queer animals and were hunted, captured and presented to the kings as entertainment. Flowers formed their dress. Their food was flower pollen and their cosmetics were made of flower perfumes.[6]

The depiction of Kinnara in early Indian art is an oft-repeated theme. The ancient sculptures of Sanchi, Barhut, Amaravati, Nagarjunakonda, Mathura, and the paintings of Ajanta depict Kinnaras invariably. Frequently, they are seen in the sculptures flanking the stupas. In this case, they hold garlands or trays containing flowers in their hands for the worship of the Stupas. Sometimes, the Kinnaras appear in the sculptures holding garland in right hand and tray in the left hand. They also appear before Bodhi-Drumas, Dharmacakras, or playing a musical instrument. As such, the portrayal of Kinnaras in early Indian sculpture art is very common.[6]

Indonesia

The images of coupled Kinnara and Kinnari can be found in Borobudur, Mendut, Pawon, Sewu, Sari, and Prambanan temples. Usually, they are depicted as birds with human heads, or humans with lower limbs of birds. The pair of Kinnara and Kinnari usually is depicted guarding Kalpataru, the tree of life, and sometimes guarding a jar of treasure.[7] A pair of Kinnara-Kinnari bas-reliefs of Sari temple is unique, depicting Kinnara as celestial humans with birds' wings attached to their backs, very similar to popular image of angels.

There are bas-relief in Borobudur depicting the story of the famous kinnari, Manohara.[8]

Thailand

The Kinnari, (usually spelt 'Kinnaree' as noted below) (Thai: กินรี) in Thai literature originates from India, but was modified to fit in with the Thai way of thinking. The Thai Kinnari is depicted as a young woman wearing an angel-like costume. The lower part of the body is similar to a bird, and should enable her to fly between the human and the mystical worlds. The most popular portrayal of Kinnaree in Thai art probably the golden figures of kinnaree adorned the Wat Phra Kaew in Bangkok, which describe a half-maiden, half-goose figure.[9]

The most famous Kinnari in Thailand is the figure known as Manora (derived from Manohara),[10] a heroine in one of the stories collected in "Pannas Jataka" a Pali tome written by a Chiangmai Buddhist monk and sage around AD 1450–1470.[11] This is supposed to be a collection of 50 stories of the past lives of the Buddha, known to Buddhists as the Jataka. The specific tale about Manora the Kinnaree was called Sudhana Jataka, after Prince Sudhana, the bodhisattva who was also the hero of the story and the husband of Manora.

Tibet

In Tibet the Kinnara is known as the Miamchi (Tibetan: མིའམ་ཅི་, Wylie: mi'am ci ) or 'shang-shang' (Tibetan: ཤང་ཤང, Wylie: shang shang ) (Sanskrit: civacivaka). This chimera is depicted either with just the head or including the whole torso of a human including the arms with the lower body as that of a winged bird. In Nyingma Mantrayana traditions of Mahayoga Buddhadharma, the shang-shang symbolizes 'enlightened activity' (Wylie: phrin las). The shang-shang is a celestial musician,[12] and is often iconographically depicted with cymbals. A homonymic play on words is evident which is a marker of oral lore: the 'shang' (Tibetan: གཆང, Wylie: gchang ) is a cymbal or gong like ritual instrument in the indigenous traditions of the Himalaya. The shang-shang is sometimes depicted as the king of the Garuda.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kinnara. |

- Kalaviṅka

- Kinnara Kingdom

- Centaur, half-human half-horse creature from Greek mythology similar to a Kinnara

- Satyr or Faun, half-human half-goat from Greek and Roman mythology that resembles the Kinnaras in behavior

- Harpy, a half-human half-bird mythological creature from the Greek mythology that resembles the Kinnara

- Siren, another mythological creature also from the Greek mythology that resembles the Kinnara and the Harpy

- Swan maiden and related tales of a mortal man who falls in love with a magical bird-woman, such as Prince Sudhana and Manohara

- Exotic Tribes of Ancient India

References

- Ghosh, Subodh (2005). Love stories from the Mahabharata, transl. Pradip Bhattacharya. New Delhi: Indialog. p. 71

- Schafer, Edward H. (1963). The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of Tʻang Exotics. University of California Press. p. 103.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 September 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 August 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Headley, Robert K. (1997). Modern Cambodian-English Dictionary, Dunwoody Press

- Mythical Animals in Indian Art. Abhinav Publications. 1985. ISBN 9780391032873.

- "Pawon". National Library of Indonesia, Temples of Indonesia.

- Miksic, John (2012). Borobudur: Golden Tales of the Buddhas. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462909100.

- Nithi Sthapitanond; Brian Mertens (2012). Architecture of Thailand: A Guide to Tradition and Contemporary Forms. Editions Didier Millet. ISBN 9789814260862.

- Schiefner, Anton; Ralston, William Shedden. Tibetan tales, derived from Indian sources. London, K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & co. ltd. 1906. pp. xlviii-l and 44-74.

- Reeja Radhakrishnan (2015). The Big Book of World Mythology. Penguin UK. ISBN 9789352140077.

- "Mythical creatures, Kinnara". Himalayan Buddhist Art.

- Mahabharata of Krishna Dwaipayana Vyasa, translated to English by Kisari Mohan Ganguli

Further reading

- Degener, Almuth. "MIGHTY ANIMALS AND POWERFUL WOMEN: On the Function of Some Motifs from Folk Literature in the Khotanese Sudhanavadana." In Multilingualism and History of Knowledge: Vol. I: Buddhism among the Iranian Peoples of Central Asia, edited by JENS E. BRAARVIG, GELLER MARKHAM J., SADOVSKI VELIZAR, SELZ GEBHARD, DE CHIARA MATTEO, MAGGI MAURO, and MARTINI GIULIANA, 103-30. Wien: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, 2013. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1vw0pkz.8.

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. "The Story of Sudhana and Manoharā: An Analysis of the Texts and the Borobudur Reliefs." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 29, no. 3 (1966): 533-58. www.jstor.org/stable/611473.