Each-uisge

The each-uisge (Scottish Gaelic: [ɛxˈɯʃkʲə], literally "water horse") is a water spirit in Scottish folklore, known as the each-uisce (anglicized as aughisky or ech-ushkya) in Ireland and cabyll-ushtey on the Isle of Man. It usually takes the form of a horse, and is similar to the kelpie but far more vicious.

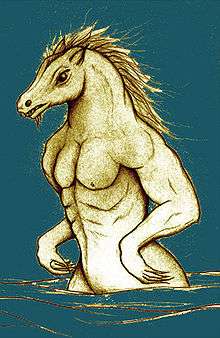

A representation of an each-uisge | |

| Grouping | Mythological |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Water spirit |

| Other name(s) | Aughisky (Ireland) |

| Country | Ireland/Scotland |

| Region | Highlands Ireland |

Folklore

Description and attributes

The each-uisge, a supernatural water horse found in the Scottish Highlands, has been described as "perhaps the fiercest and most dangerous of all the water-horses" by the folklorist Katharine Briggs.[1] Often mistaken for the kelpie (which inhabits streams and rivers), the each-uisge lives in the sea, sea lochs, and fresh water lochs.[1] The each-uisge is a shape-shifter, disguising itself as a fine horse, pony, a handsome man or an enormous bird such as a boobrie.[1] If, while in horse form, a man mounts it, he is only safe as long as the each-uisge is ridden in the interior of land. However, the merest glimpse or smell of water means the end of the rider, for the each-uisge's skin becomes adhesive and the creature immediately goes to the deepest part of the loch with its victim. After the victim has drowned, the each-uisge tears him apart and devours the entire body except for the liver, which floats to the surface.[1]

In its human form it is said to appear as a handsome man, and can be recognised as a mythological creature only by the water weeds[2] or profuse sand and mud in its hair.[3] Because of this, people in the Highlands were often wary of lone animals and strangers by the water's edge, near where the each-uisge was reputed to live.

Cnoc-na-Bèist ("Hillock of the Monster") is the name of a knoll on the Isle of Lewis where an each-uisge was slain by the brother of a woman it tried to seduce, by the freshwater Loch a’ Mhuileinn ("Loch of the Mill").[3]

Along with its human victims, cattle and sheep were also often prey to the each-uisge, and it could be lured out of the water by the smell of roasted meat. One story from John McKay's More West Highland Tales runs thus:

A blacksmith from Raasay lost his daughter to the each-uisge. In revenge the blacksmith and his son made a set of large hooks, in a forge they set up by the loch side. They then roasted a sheep and heated the hooks until they were red hot. At last a great mist appeared from the water and the each-uisge rose from the depths and seized the sheep. The blacksmith and his son rammed the red-hot hooks into its flesh and after a short struggle dispatched it. In the morning there was nothing left of the creature apart from a jelly-like substance.

The Scottish folklorist John Gregorson Campbell recorded numerous tales and traditions concerning the each-uisge. In one account a man who was about to be carried by the water horse into the loch was able to save himself by placing both feet on either side of a narrow gateway the horse was running through, thereby wrenching himself off its back through sheer force. A boy who had touched the horse with his finger and gotten stuck was able to save himself by cutting it off. A Highland freebooter encountered a water horse in its human form and fired his gun at it twice with no effect, but when he loaded it with a coin made of silver and fired again the man retreated and plunged back into the loch. The each-uisge is unpredictable. It has been known to venture forth on land and attack solitary individuals, while in other accounts it will allow itself to be used as farm labour until its owner gets on its back and is carried into the loch. In their predatory hunger water horses may even turn on their own kind if the scent of a previous human rider is strong enough on the monster's body.[4]

Water horses and women

The each-uisge also has a particular desire for human women. Campbell states that "any woman upon whom it set its mark was certain at last to become its victim." A young woman herding cattle encountered a water horse in the form of a handsome young man who laid his head in her lap and fell asleep. When he stretched himself she discovered that he had horse's hooves and quietly made her escape (in variations of the tale she finds the presence of water weeds or sand in his hair). In another account a water horse in human shape came to a woman's house where she was alone and attempted to court her, but all he got for his unwanted advances was boiling water hurled between his legs. He ran from the house roaring in pain. In a third tale a father and his three sons conspired to kill a water horse that came to the house to see the daughter. When they grabbed the young man he reverted to his equine form and would have carried them into the loch, but in the struggle they managed to slay him with their dirks. Despite its amorous tendencies, however, the each-uisge is just as likely to simply devour women in the same manner as its male victims.[4]

Variants

The aughisky or Irish water horse is similar in many respects to the Scottish version. It sometimes comes out of the water to gallop on land and, despite the danger, if the aughisky can be caught and tamed then it will make the finest of steeds provided it is not allowed to glimpse the ocean.[5]

The cabyll-ushtey (or cabbyl-ushtey), the Manx water horse, is just as ravenous as the each-uisge though there are not as many tales told about it. One of them recounts how a cabbyl-ushtey emerged from the Awin Dhoo (Black River) and devoured a farmer's cow, then later it took his teenaged daughter.[6]

Origins

The appearance of the each-uisge on the Isle of Skye was described by Gordon in 1995 as having a parrot-like beak, and this, with its habit of diving suddenly, could be from real-life encounters with a sea turtle such as the leatherback sea turtle.[7]

References

- Briggs, Katharine (1976). An Encyclopedia of Fairies, Hobgoblins, Brownies, Boogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books. pp. 115–16. ISBN 0-394-73467-X.

- Varner, Gary R. (2007), Creatures in the Mist: Little People, Wild Men and Spirit Beings around the World: A Study in Comparative Mythology, Algora, p. 24, ISBN 978-0-87586-545-4 – via Questia Online Library (subscription required)

- MacPhail, Malcolm (1896). "Folklore from the Hebrides" (PDF). Folklore. 7 (4): 400–04. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1896.9720386.

- Campbell, John Gregorson (1900). Superstitions of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Glasgow: James MacLehose and Sons. pp. 203–15.

- Yeats, William Butler (1888). Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry. London: Walter Scott. p. 94.

- Gill, W. Walter (1929). A Manx Scrapbook Arrowsmith. Ch. 4.

- Parsons, E.C.M. (2004). "Sea monsters and mermaids in Scottish folklore: Can these tales give us information on the historic occurrence of marine animals in Scotland?". Anthrozoös: A Multidisciplinary Journal of the Interactions of People and Animals. 17 (1): 73–80. doi:10.2752/089279304786991936. eISSN 1753-0377. ISSN 0892-7936.