Sokoto Caliphate

The Sokoto Caliphate was an independent Sunni Muslim Caliphate in West Africa that was founded during the jihad of the Fulani War in 1804 by Usman dan Fodio.[1] It was abolished when the British conquered the area in 1903 and established the Northern Nigeria Protectorate.

Caliphal State in the Bilād as-Sūdān Daular Khalifar Sakkwato al-Khilāfat fi'l-Bilād as-Sūdān دولة الخلافة في بلاد السودان | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1804–1903 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Flag | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Anthem: Imperial Drum Beat | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

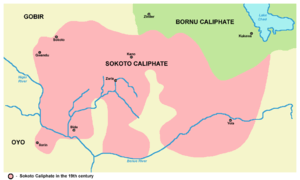

Sokoto Caliphate, 19th century | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Theocratic hereditary monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic (official), Hausa, Fula | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| List of Sultans of Sokoto | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1804-1832 | Usman dan Fodio (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1896–1903 | Muhammadu Attahiru (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Grand Vizier | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• ???–1832 | Gidago dan Laima (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1890-1903 | Muhammadu al-Bukhari (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Shura | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Founded | 4 Feb 1804 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Tabkin Kwatto | 1804 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• First Succession Crisis | 1832 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1837 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Proclamation of the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria | 1 Jan 1897 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Second Battle of Burmi | 29 July 1903 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Dirham | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Developed in the context of multiple independent Hausa Kingdoms, at its height, the caliphate linked over 30 different emirates and over 10 million people in the most powerful state in the region and one of the most significant empires in Africa in the nineteenth century. The caliphate was a loose confederation of emirates that recognized the suzerainty of the Amir al-Mu'minin, the Sultan of Sokoto.[2] The caliphate brought decades of economic growth throughout the region. An estimated 1-2.5 million non-Muslim slaves were captured during the Fulani War.[3] Slaves provided labor for plantations and were provided an opportunity to become Muslims.[4]

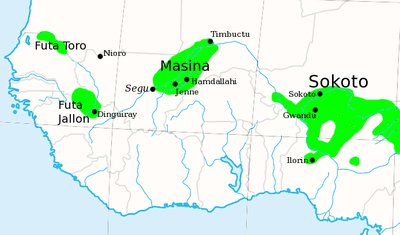

Although the British abolished the political authority of the caliphate, the title of sultan was retained and remains an important religious position for Sunni Muslims in the region to the current day.[5] Usman dan Fodio's jihad provided the inspiration for a series of related jihads in other parts of the Sudanian Savanna and the Sahel far beyond the borders of what is now Nigeria that led to the foundation of Islamic states in the regions that would become Senegal, Mali, Ivory Coast, Chad, the Central African Republic, and Sudan.[2]

Founding and expansion (1804–1903)

Background

The major power in the region in the 17th and 18th centuries had been the Bornu Empire. However, revolutions and the rise of new powers decreased the power of the Bornu empire and by 1759 its rulers had lost control over the oasis town of Bilma and access to the Trans-Saharan trade.[6] Vassal cities of the empire gradually became autonomous, and the result by 1780 was a political array of independent states in the region.[6]

The fall of the Songhai Empire in 1591 to Morocco also had freed much of the central Bilad as-Sudan, and a number of Hausa sultanates led by different Hausa aristocracies had grown to fill the void. Three of the most significant to develop were the sultanates of Gobir, Kebbi (both in the Rima River valley), and Zamfara, all in present-day Nigeria.[6][7] These kingdoms engaged in regular warfare against each other, especially in conducting slave raids. In order to pay for the constant warfare, they imposed high taxation on their citizens.[8]

The region between the Niger River and Lake Chad was largely populated with the Hausa, the Fulani, and other ethnic groups that had immigrated to the area such as the Tuareg. Much of the Hausa population had settled in the cities throughout the region and became urbanized. The Fulani, in contrast, had largely remained a pastoral community, herding cattle, goats and sheep, and populating grasslands between the towns throughout the region. With increasing trade, a good number of Fulani settled in towns, forming a distinct minority.[6][8]

Much of the population had converted to Islam in the centuries before; however, local pagan beliefs persisted in many areas, especially in the aristocracy.[7] In the end of the 1700s, an increase in Islamic preaching occurred throughout the Hausa kingdoms. A number of the preachers were linked in a shared Tariqa of Islamic study.[6] Maliki scholars were invited or traveled to the Hausa lands from the Maghreb and joined the courts of some sultanates such as in Kano. These scholars preached a return to adherence to Islamic tradition. The most important of these scholars is Muhammad al-Maghili, who brought the Maliki jurisprudence to Nigeria.

Jihad Movement

Usman dan Fodio, an Islamic scholar and an urbanized Fulani, had been actively educating and preaching in the city of Gobir with the approval and support of the Hausa leadership of the city. However, when Yunfa, a former student of dan Fodio, became the sultan of Gobir, he restricted dan Fodio's activities, eventually forcing him into exile in Gudu.[6][9] A large number of people left Gobir to join dan Fodio, who also began to gather new supporters from other regions. Feeling threatened by his former teacher, Yunfa declared war on dan Fodio[9] on February 21, 1804.

Usman dan Fodio was elected "Commander of the Faithful" (Amir al-Mu'minin) by his followers,[9] marking the beginning of the Sokoto state. Usman dan Fodio then created a number of flag bearers amongst those following him, creating an early political structure of the empire.[6] Declaring a jihad against the Hausa kings, dan Fodio rallied his primarily Fulani "warrior-scholars" against Gobir.[9] Despite early losses at the Battle of Tsuntua and elsewhere, the forces of dan Fodio began taking over some key cities starting in 1805.[6] The Fulani used guerrilla warfare to turn the conflict in their favor, and gathered support from the civilian population, which had come to resent the despotic rule and high taxes of the Hausa kings. Even some non-Muslim Fulani started to support dan Fodio.[9] The war lasted from 1804 until 1808, and resulted in thousands of deaths.[9][6] The forces of dan Fodio were able to capture the states of Katsina and Daura, the important kingdom of Kano in 1807,[6] and finally conquered Gobir in 1809.[9] In the same year, Muhammed Bello, the son of dan Fodio, founded the city of Sokoto, which became the capital of the Sokoto state.[8]

The jihad had created "a new slaving frontier on the basis of rejuvenated Islam."[3] By 1900 the Sokoto state had "at least 1 million and perhaps as many as 2.5 million slaves", second only to the United States (which had 4 million in 1860) in size among all modern slave societies.[3] However, there was far less of a distinction between slaves and their masters in the Sokoto state.[10]

Expansion of the Sokoto State

From 1808 until the mid-1830s, the Sokoto state expanded, gradually annexing the plains to the west and key parts of Yorubaland. It became one of the largest states in Africa, stretching from modern-day Burkina Faso to Cameroon and including most of northern Nigeria and southern Niger. At its height, the Sokoto state included over 30 different emirates under its political structure.[5]

The political structure of the state was organized with the sultan of Sokoto ruling from the city of Sokoto (and for a brief period under Muhammad Bello from Wurno). The leader of each emirate was appointed by the sultan as the flag bearer for that city but was given wide independence and autonomy.[11]

Much of the growth of the state occurred through the establishment of an extensive system of ribats as part of the consolidation policy of Muhammed Bello, the second Sultan.[12] Ribats were established, founding a number of new cities with walled fortresses, schools, markets, and other buildings. These proved crucial in expansion through developing new cities, settling the pastoral Fulani people, and supporting the growth of plantations which were vital to the economy.[4]

By 1837, the Sokoto state had a population of around 10 million people.[5]

Administrative structure

The Sokoto state was largely organized around a number of largely independent emirates pledging allegiance to the sultan of Sokoto. The administration was initially built to follow those of Muhammad during his time in Medina, but also the theories of Al-Mawardi in "The Ordinances of Government".[11] The Hausa kingdoms prior to Usman dan Fodio had been run largely through hereditary succession.

The early rulers of Sokoto, dan Fodio and Bello, abolished systems of hereditary succession, preferring leaders to be appointed by virtue of their Islamic scholarship and moral standing.[8] Emirs were appointed by the sultan; they traveled yearly to pledge allegiance and deliver taxes in the form of crops, cowry shells, and slaves.[5] When a sultan died or retired from the office, an appointment council made up of the emirs would select a replacement.[11] Direct lines of succession were largely not followed, although each sultan claimed direct descent from dan Fodio.

The major administrative division was between Sokoto and the Gwandu Emirate. In 1815, Usman dan Fodio retired from the administrative business of the state and divided the area taken over during the Fulani War with his brother Abdullahi dan Fodio ruling in the west with the Gwandu Emirate and his son Muhammed Bello taking over administration of the Sokoto Sultanate. The Emir at Gwandu retained allegiance to the Sokoto Sultanate and spiritual guidance from the sultan, but the emir managed the separate emirates under his supervision independently from the sultan.[11]

The administrative structure of loose allegiances of the emirates to the sultan did not always function smoothly. There was a series of revolutions by the Hausa aristocracy in 1816–1817 during the reign of Muhammed Bello, but the sultan ended these by granting the leaders titles to land.[4] There were multiple crises that arose during the 19th century between the Sokoto Sultanate and many of the subservient emirates: notably, the Adamawa Emirate and the Kano Emirate.[13] A serious revolt occurred in 1836 in the city-state of Gobir, which was crushed by Muhammed Bello at the Battle of Gawakuke.[14]

The Sufi community throughout the region proved crucial in the administration of the state. The Tariqa brotherhoods, most notably the Qadiriyya, to which every successive sultan of Sokoto was an adherent,[15] provided a group linking the distinct emirates to the authority of the sultan. Scholars Burnham and Last claim that this Islamic scholarship community provided an "embryonic bureaucracy" which linked the cities throughout the Sokoto state.[11]

Economy

After the establishment of the Caliphate, there were decades of economic growth throughout the region, particularly after a wave of revolts in 1816–1817.[4] They had significant trade over the trans-Saharan routes.[4]

After the Fulani War, all land in the empire was declared waqf or owned by the entire community. However, the Sultan allocated land to individuals or families, as could an emir. Such land could be inherited by family members but could not be sold.[7] Exchange was based largely on slaves, cowries or gold.[4] Major crops produced included cotton, indigo, kola and shea nuts, grain, rice, tobacco, and onion.[4]

Slavery remained a large part of the economy, although its operation had changed with the end of the Atlantic slave trade. Slaves were gained through raiding and via markets as had operated earlier in West Africa.[4] The founder of the Caliphate allowed slavery only for non-Muslims; slavery was viewed as a process to bring such peoples into the Muslim community.[8] Around half of the Caliphate's population was enslaved in the 19th century.[16] The expansion of agricultural plantations under the Caliphate was dependent on slave labor however. These plantations were established around the ribats, and large areas of agricultural production took place around the cities of the empire.[4] The institution of slavery was mediated by the lack of a racial barrier among the peoples, and by a complex and varying set of relations between owners and slaves, which included the right to accumulate property by working on their own plots, manumission, and the potential for slaves to convert and become members of the Islamic community.[4] There are historical records of slaves reaching high levels of government and administration in the Sokoto Caliphate.[10] Its commercial prosperity was also based on Islamic traditions, market integration, internal peace and an extensive export-trade network.[17]

Scholarship

Islamic scholarship was a crucial aspect of the Caliphate from its founding. Sultan Usman dan Fodio, Sultan Muhammed Bello, Emir Abdullahi dan Fodio, Sultan Abu Bakr Atiku, and Nana Asma'u devoted significant time to chronicling histories, writing poetry, and Islamic studies. A number of manuscripts are available and they provide crucial historical information and important spiritual texts.[5] This role did diminish after the reign of Bello and Atiku.

Decline and fall

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Northern Nigeria |

|

Timeline

|

|

By ethnicity

|

|

By topic

|

|

By Province

|

European attention had been focusing on the region for colonial expansion for much of the last part of the 19th century. The French in particular had sent multiple exploratory missions to the area to assess colonial opportunities after 1870.

French explorer Parfait-Louis Monteil visited Sokoto in 1891 and noted that the Caliphate was at war with the Emir of Argungu, defeating Argungu the next year. Monteil claimed that Fulani power was tottering because of the war and the accession of the unpopular Caliph Abderrahman dan Abi Bakar.[18]

However, following the Berlin Conference, the British had expanded into Southern Nigeria, and by 1902 had begun plans to move into the Sokoto Caliphate. British General Frederick Lugard used rivalries between many of the emirs in the south and the central Sokoto administration to prevent any defense as he worked toward the capital.[19] As the British approached the city of Sokoto, the new Sultan Muhammadu Attahiru I organized a quick defense of the city and fought the advancing British-led forces. The British force quickly won, sending Attahiru I and thousands of followers on a Mahdist hijra.[20]

On March 13, 1903 at the grand market square of Sokoto, the last Vizier of the Caliphate officially conceded to British Rule. The British appointed Muhammadu Attahiru II as the new Caliph.[20] Fredrick Lugard abolished the Caliphate, but retained the title Sultan as a symbolic position in the newly organized Northern Nigeria Protectorate.[5] This remnant became known as "Sokoto Sultanate Council".[21] In June 1903, the British defeated the remaining forces of Attahiru I and killed him; by 1906 resistance to British rule had ended.

Legacy

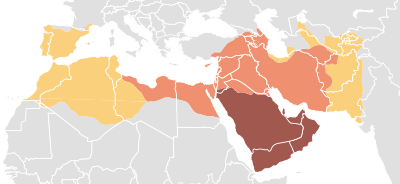

| Caliphate خِلافة |

|---|

|

|

Main caliphates |

|

Parallel caliphates |

|

|

Although it has lost its former political power, the Sokoto Sultanate Council continues to exist and the Sokoto Sultans are still "leading figures in Nigerian society". Even the Presidents of Nigeria have sought their support.[9]

Due to its impact, the Sokoto Caliphate is also revered by Islamists in modern Nigeria. For example, the Jihadist militant group Ansaru has vowed to revive the Sokoto Caliphate in order to restore the "lost dignity of Muslims in black Africa".[22]

References

- McKay, Hill, Buckler, Ebrey, Beck, Crowston, Weisner-Hanks. A History of World Societies. 8th edition. Volume C - From 1775 to the Present. 2009 by Bedford/St. Martin's. ISBN 978-0-312-68298-9. "The most important of these revivalist states, the enormous Sokoto caliphate, illustrates the general pattern. It was founded by Usuman dan Fodio (1754-1817), an inspiring Muslim teacher who first won zealous followers among both the Fulani herders and Hausa peasants in the Muslim state of Gobir in the northern Sudan." p. 736.

- Metz, Helen Chapin, ed. (1991). "Usman dan Fodio and the Sokoto Caliphate". Nigeria: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- McKay, John P.; Hill, Bennett D. (2011). A History of World Societies, Volume 2: Since 1450, Volume 2. Macmillan. p. 755. ISBN 9780312666934.

- Lovejoy, Paul E. (1978). "Plantations in the Economy of the Sokoto Caliphate". The Journal of African History. 19 (3): 341–368. doi:10.1017/s0021853700016200.

- Falola, Toyin (2009). Historical Dictionary of Nigeria. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press.

- Maishanu, Hamza Muhammad; Isa Muhammad Maishanu (1999). "The Jihad and the Formation of the Sokoto Caliphate". Islamic Studies. 38 (1): 119–131.

- Swindell, Kenneth (1986). "Population and Agriculture in the Sokoto-Rima Basin of North-West Nigeria: A Study of Political Intervention, Adaptation and Change, 1800–1980". Cahiers d'Études Africaines. 26 (101): 75–111. doi:10.3406/cea.1986.2167.

- Chafe, Kabiru Sulaiman (1994). "Challenges to the Hegemony of the Sokoto Caliphate: A Preliminary Examination". Paideuma. 40: 99–109.

- Comolli (2015), p. 15.

- Stilwell, Sean (2000). "Power, Honour and Shame: The Ideology of Royal Slavery in the Sokoto Caliphate". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 70 (3): 394–421. doi:10.3366/afr.2000.70.3.394.

- Burnham, Peter; Murray Last (1994). "From Pastoralist to Politician: The Problem of a Fulbe "Aristocracy"". Cahiers d'Études Africaines. 34 (133): 313–357. doi:10.3406/cea.1994.2055.

- Salau, Mohammed Bashir (2006). "Ribats and the Development of Plantations in the Sokoto Caliphate: A Case Study of Fanisau". African Economic History. 34 (34): 23–43. doi:10.2307/25427025. JSTOR 25427025.

- Njeuma, Martin Z. (2012). Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902. Cameroon: Langa.

- Last, Murray (1967). The Sokoto Caliphate. New York: Humanities Press. pp. 74–75.

- Hiskett, M. The Sword of Truth; the Life and times of the Shehu Usuman Dan Fodio. New York: Oxford UP, 1973. Print.

- "Welcome to Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 323. ISBN 9781107507180.

- Claire Hirshfield (1979). The diplomacy of partition: Britain, France, and the creation of Nigeria, 1890-1898. Springer. p. 37ff. ISBN 90-247-2099-0. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- The Cambridge History of Africa: 1870-1905. London: Cambridge University Press. 1985. p. 276.

- Falola, Toyin (2009). Colonialism and Violence in Nigeria. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Claire Hirshfield (1979). The diplomacy of partition: Britain, France, and the creation of Nigeria, 1890-1898. Springer. p. 37ff. ISBN 90-247-2099-0. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- Comolli (2015), p. 103.

- Comolli, Virginia (2015). Boko Haram: Nigeria's Islamist Insurgency. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781849044912.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)