Sodium triphosphate

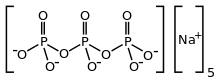

Sodium triphosphate (STP), also sodium tripolyphosphate (STPP), or tripolyphosphate (TPP),[1]) is an inorganic compound with formula Na5P3O10. It is the sodium salt of the polyphosphate penta-anion, which is the conjugate base of triphosphoric acid. It is produced on a large scale as a component of many domestic and industrial products, especially detergents. Environmental problems associated with eutrophication are attributed to its widespread use.

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Pentasodium triphosphate | |

| Other names

sodium tripolyphosphate, polygon, STPP | |

| Identifiers | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.944 |

| E number | E451 (thickeners, ...) |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| Properties | |

| Na5P3O10 | |

| Molar mass | 367.864 g/mol |

| Appearance | white powder |

| Density | 2.52 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 622 °C (1,152 °F; 895 K) |

| 14.5 g/100 mL (25 °C) | |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | ICSC 1469 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions |

Trisodium phosphate Tetrasodium pyrophosphate Sodium hexametaphosphate |

Other cations |

Pentapotassium triphosphate |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Preparation and properties

Sodium tripolyphosphate is produced by heating a stoichiometric mixture of disodium phosphate, Na2HPO4, and monosodium phosphate, NaH2PO4, under carefully controlled conditions.[2]

- 2 Na2HPO4 + NaH2PO4 → Na5P3O10 + 2 H2O

In this way, approximately 2 million tons are produced annually.

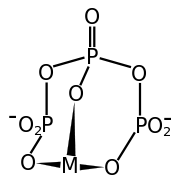

STPP is a colourless salt, which exists both in anhydrous form and as the hexahydrate. The anion can be described as the pentanionic chain [O3POP(O)2OPO3]5−.[3][4] Many related di-, tri-, and polyphosphates are known including the cyclic triphosphate P3O93−. It binds strongly to metal cations as both a bidentate and tridentate chelating agent.

Uses

In detergents

The majority of STPP is consumed as a component of commercial detergents. It serves as a "builder," industrial jargon for a water softener. In hard water (water that contains high concentrations of Mg2+ and Ca2+), detergents are deactivated. Being a highly charged chelating agent, TPP5− binds to dications tightly and prevents them from interfering with the sulfonate detergent.[5]

Food applications

STPP is a preservative for seafood, meats, poultry, and animal feeds.[5] It is common in food production as E number E451. In foods, STPP is used as an emulsifier and to retain moisture. Many governments regulate the quantities allowed in foods, as it can substantially increase the sale weight of seafood in particular. The United States Food and Drug Administration lists STPP as "generally recognized as safe."

Other uses

Other uses (hundreds of thousands of tons/year) include ceramics (decrease the viscosity of glazes up to a certain limit), leather tanning (as masking agent and synthetic tanning agent - SYNTAN), anticaking, setting retarders, flame retardants, paper, anticorrosion pigments, textiles, rubber manufacture, fermentation, antifreeze."[5] TPP is used as a polyanion crosslinker in polysaccharide based drug delivery.[6] toothpaste[7][8][9][10][11][12][13]

Health effects

High serum phosphate concentration has been identified as a predictor of cardiovascular events and mortality. Whilst phosphate is present in the body and food in organic forms, inorganic forms of phosphate such as sodium triphosphate are readily adsorbed and can result in elevated phosphate levels in serum.[14] Salts of polyphosphate anions are moderately irritating to skin and mucous membranes because they are mildly alkaline.[1]

Environmental effects

In 2000, the worldwide consumption of STPP was estimated to be approximately 2,000,000 tonnes.[5] Because it is very water-soluble, it is not significantly transferred to sewage sludge, and therefore to soil by sludge spreading. No environmental risk related to STPP use in detergents is indicated in soil or air. As an ingredient of household cleaning products, STPP present in domestic waste waters is mainly discharged to the aquatic compartment, directly, via waste water treatment plants, via septic tanks, infiltration or other autonomous waste water systems.

As STPP is an inorganic substance, biodegradation studies are not applicable. However, STPP can be hydrolysed, finally to orthophosphate, which can be assimilated by algae and/or by micro-organisms. STPP thus ends up being assimilated into the natural phosphorus cycle. Reliable published studies confirm biochemical understanding, showing that STPP is progressively hydrolysed by biochemical activity in contact with waste waters (in sewerage pipes and within sewage works) and also in the natural aquatic environment. This information enabled the calculation of “worst case” predicted environmental concentrations using the EUSES model and the HERA detergent scenario. A default regional release of 10% was applied instead of the 7% regional release indicated in the HERA detergent scenario. Reliable acute aquatic ecotoxicity studies are available which show that STPP is not toxic to aquatic organisms: all EC/LC50 values are above 100 mg/l (Daphnia, fish, algae). Because of this, and because of the only temporary presence of STPP in the aquatic environment (due to hydrolysis), no studies have been carried out to date concerning the chronic effects of STPP on these aquatic organisms. Predicted no-effect concentrations were therefore calculated for the aquatic environment and sediments on the basis of the acute aquatic ecotoxicity results.

Effects of wastewater containing phosphorus

Detergents containing phosphorus contribute, together with other sources of phosphorus, to the eutrophication of many fresh waters.[1] Eutrophication is an increase in chemical nutrients—typically compounds containing nitrogen or phosphorus—in an ecosystem. It may occur on land or in water. The term is, however, often used to mean the resultant increase in the ecosystem's primary productivity (excessive plant growth and decay), and further effects including lack of oxygen and severe reductions in water quality and fish and other animal populations.

Phosphorus can theoretically generate its weight 500 times in algae.[15] Whereas the primary production in marine waters is mainly nitrogen-limited, fresh waters are considered to be phosphorus-limited. A large part of the sewage effluents in many countries is released untreated into freshwater recipients thus bringing phosphorus with it. However, the amount from urban and household use is less than 5% of the phosphorus run-off due to agricultural fertilizer use and therefore both the use and the reduction in use of phosphorus containing compounds in household items does not significantly affect the overall environmental balance of phosphorus and is not a significant contributing factor to water eutrophication.

See also

References

- Complexing agents, Environmental and Health Assessment of Substances in Household Detergents and Cosmetic Detergent Products, Danish Environmental Protection Agency, Accessed 2008-07-15

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- Corbridge, D. E. C. (1 March 1960). "The crystal structure of sodium triphosphate, Na5P3O10, phase I". Acta Crystallographica. 13 (3): 263–269. doi:10.1107/S0365110X60000583.

- Davies, D. R.; Corbridge, D. E. C. (1 May 1958). "The crystal structure of sodium triphosphate, Na5P3O10, phase II". Acta Crystallographica. 11 (5): 315–319. doi:10.1107/S0365110X58000876.

- Schrödter, Klaus; Bettermann, Gerhard; Staffel, Thomas; Wahl, Friedrich; Klein, Thomas; Hofmann, Thomas (2008). "Phosphoric Acid and Phosphates". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_465.pub3. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- Calvo, P.; Remuñán‐López, C.; Vila-Jato, J. L.; Alonso, M. J. (3 January 1997). "Novel hydrophilic chitosan-polyethylene oxide nanoparticles as protein carriers". Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 63 (1): 125–132. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(19970103)63:1<125::AID-APP13>3.0.CO;2-4.

- Saxton, C. A.; Ouderaa, F. J. G. (January 1989). "The effect of a dentifrice containing zinc citrate and Triclosan on developing gingivitis". Journal of Periodontal Research. 24 (1): 75–80. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0765.1989.tb00860.x. PMID 2524573.

- Lobene, RR; Weatherford, T; Ross, NM; Lamm, RA; Menaker, L (1986). "A modified gingival index for use in clinical trials". Clinical Preventive Dentistry. 8 (1): 3–6. PMID 3485495.

- Lobene, RR; Soparkar, PM; Newman, MB (1982). "Use of dental floss. Effect on plaque and gingivitis". Clinical Preventive Dentistry. 4 (1): 5–8. PMID 6980082.

- Mankodi, Suru; Bartizek, Robert D.; Leslie Winston, J.; Biesbrock, Aaron R.; McClanahan, Stephen F.; He, Tao (January 2005). "Anti-gingivitis efficacy of a stabilized 0.454% stannous fluoride/sodium hexametaphosphate dentifrice. A controlled 6-month clinical trial". Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 32 (1): 75–80. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00639.x. PMID 15642062.

- Mankodi, S; Petrone, DM; Battista, G; Petrone, ME; Chaknis, P; DeVizio, W; Volpe, AR; Proskin, HM (1997). "Clinical efficacy of an optimized stannous fluoride dentifrice, Part 2: A 6-month plaque/gingivitis clinical study, northeast USA". Compendium of Continuing Education in Dentistry. 18 Spec No: 10–5. PMID 12206029.

- Mallatt, Mark; Mankodi, Suru; Bauroth, Karen; Bsoul, Samer A.; Bartizek, Robert D.; He, Tao (September 2007). "A controlled 6-month clinical trial to study the effects of a stannous fluoride dentifrice on gingivitis". Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 34 (9): 762–767. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01109.x. PMID 17645550.

- Lang, Niklaus P. (1990). "Epidemiology of periodontal disease". Archives of Oral Biology. 35: S9–S14. doi:10.1016/0003-9969(90)90125-t. PMID 2088238.

- Ritz, Eberhard; Hahn, Kai; Ketteler, Markus; Kuhlmann, Martin K; Mann, Johannes (2012). "Phosphate Additives in Food—a Health Risk". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 109 (4): 49–55. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2012.0049. PMC 3278747. PMID 22334826.

- Wetzel 1983