Salah

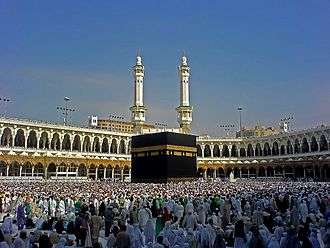

Salah or Salat (Arabic: ٱلصَّلَاة aṣ-ṣalāh, Arabic: ٱلصَّلَوَات aṣ-ṣalawāt, meaning "prayer", "supplication", "blessing" and "commendation";[1] also known as Namāz (from Persian: نماز))[2] among most non-Arab Muslims, is the second of the five pillars in the Islamic faith as daily obligatory standardized prayers. It is a physical, mental, and spiritual act of worship that is observed five times every day at prescribed times. While facing towards the Kaaba in Mecca,[3] Muslims pray first standing and later kneeling or sitting on the ground, reciting from the Qur'an and glorifying and praising God as they bow and prostrate themselves in between. Ritual purity is a precondition.

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on Islam Aqidah |

|---|

|

|

Six articles of belief

|

|

Including: 1Al-Ahbash; Barelvis 2Deobandi 3Salafis (Ahl-i Hadith & Wahhabis) 4Sevener-Qarmatians, Assassins & Druzes 5Alawites, Qizilbash & Bektashism; 6Jahmīyya 7Ajardi, Azariqa, Bayhasiyya, Najdat & Sūfrī 8Nukkari; 9Bektashis & Qalandaris; Mevlevis, Süleymancıs & various Ṭarīqah 10Bahshamiyya, Bishriyya & Ikhshîdiyya |

Salah is composed of repetitive cycles of bows and prostrations, divided into prescribed units called a rakʿah. The number of rakaʿahs varies according to the time of day.

Terminology

Etymology

Ṣalāh ([sˤɑˈlɑː] صَلَاة) is an Arabic word that means to pray or bless.[4] It also means "contact," "communication," or "connection".[5]

English usage

The word salāh is used by English-speakers only to refer to the formal obligatory prayers of Islam. The word "prayer" may also be used to translate different elements of Muslim worship, such as duʿāʾ (دُعَاء "invocation, appeal, supplication") and dhikr (ذِكْر "remembrance, mention, litany").[6]

Namaz

In non-Arab Muslim countries the most widespread term is the Persian word namāz (نماز). It is used by speakers of the Indo-Iranian languages (e.g., Persian, Kurdish, Bengali, Urdu, Balochi, Hindi),[7] as well as by speakers of Turkish, Azerbaijani, Russian, Chinese, Bosnian and Albanian. In the North Caucasus, the term is lamaz (ламаз) in Chechen, chak (чак) in Lak and kak in Avar (как). In Malaysia and Indonesia, the term solat is used, as well as a local term sembahyang (meaning "communication", from the words sembah - worship, and hyang - god or deity).[8]

Salah in the Quran

The noun ṣalāh (صلاة) is used 82 times in the Qur'an, with about 15 other derivatives of its triliteral root ṣ-l[9]. Words connected to salah (such as mosque, wudu, dhikr, etc.) are used in approximately one-sixth of Qur'anic verses.[10] "Surely my prayer, and my sacrifice and my life and my death are (all) for God",[11][lower-alpha 1] and "I am Allah, there is no god but I, therefore serve Me and keep up prayer for My remembrance"[12][lower-alpha 2] are both examples of this.

Exegesis of the Qur'an can give four dimensions of salah. First, in order to commend God's servants, God, together with the angels, do salah ("blessing, salutations")[13][lower-alpha 3] Second, salah is done involuntarily by all beings in Creation, in the sense that they are always in contact with God by virtue of Him creating and sustaining them.[14][lower-alpha 4] Third, Muslims voluntarily offer salah to reveal that it is the particular form of worship that belongs to the prophets.[lower-alpha 5] Fourth, salah is described as the second pillar of Islam.[4]

Purpose and importance

.jpg)

The primary purpose of Salah is to act as a person's communication with Allah.[15] Purification of the heart is the ultimate religious objective of Salah.[16]

Conditions

Salah is an obligatory ritual for all Muslims, except for those who are prepubescent, menstruating and experiencing bleeding in the 40 days after childbirth, according to Sunnis.[17]

There are some conditions that make salah invalid, and some that make salah correct.[18]

According to one view among many, if one ignores the following conditions, their salah is invalid:[18]

- Facing the Qibla, with the chest facing the direction of the Kaaba. The ill and the old are allowed leniency with posture;

- Being in a state of Tahara, usually achieved by a short ritual washing called wudu;

- Being sane and able to distinguish between right and wrong;[19]

- Not offering salah in the pathway of people (unless a stationary object is placed in front, obstructing the people's way), in a graveyard or disrespectful places, on land which has been taken by force;

- Covering one's nakedness (awrah).[20]

- Laughing or speaking, or any unnecessary movements during the salah;

- Flatulence;

- Burping loudly in such a way that it disturbs other worshippers; and

- Reading the necessary surahs too loudly, in a way that disturbs other worshippers

Other conditions for salah include:[18]

- Women not praying during their menstruation and for a period of time after childbirth.[21]

- Covering of the whole body; and

- Praying within the time determined for each salah [22]

Prostration of forgetfulness

Most mistakes in Salah can be compensated for by prostrating twice at the end of the prayer.[23]

Gestures and postures

Each Salah is made up of repeating units or cycles called rakats (singular rakah). There may be two to four units.

Each unit consists of specific movements and recitations. On the major elements there is consensus, but on minor details there may be different views. Between each position there is a very slight pause.

Orthostasis (qiyām)

Salah is begun in a standing position (although people who find it physically difficult can offer salah in a way suitable for them).[4]

Intention (niyyah)

Intention is a prerequisite for salah, and what distinguishes real worship from 'going through the motions'. Some authorities hold that intention suffices in the heart, and some require that it be spoken, usually under the breath.[24] But there is no evidence that the Islamic prophet Muhammad or any of his companions ever uttered a niyyah aloud before prayer.

Consecratory magnification (takbīrat al-iḥrām)

One says Allāhu akbar (اَللهُ أَكْبَرْ, "God is greater/greatest"), a formula known as takbīr (literally "magnification [of God]"). This opening takbīr is known as takbīrat al-iḥrām or takbīrat at-taḥrīmah. From this point forward one praying may not converse, eat, or do other worldly things: the aim is to be alone with God. For many Muslims, the consecration is said with the hands raised and thumbs placed behind the earlobes, as shown.[25] One then lowers one's hands.[26][27] Some Muslims afterwards add a supplication praising Allah, such as:[28]

- سُبْحَاْنَكَ اَلْلّٰھُمَّ وَبِحَمدِكَ وَتَبَارَكَ اسْمُكَ وَتَعَالٰی جَدُّكَ وَلَا اِلٰهَ غَیْرُكَ

- subḥānaka allāhumma wa-bi-ḥamdika wa-tabāraka-smuka wa-taʿālā jadduka wa-lā ʾilāha ġayruk.[25]

- "Glory be to You, O God, along with Your praise, and blessed is Your name, and high is Your majesty, and there is no god other than You."

Readings/recitation (qiraʾat)

Still standing, the next principal act is to recite the first chapter of the Qur'an, the Fatiha.[29] This chapter takes the form of a supplication, at the heart of which is a plea for guidance "to the straight path". Many Muslims precede the Fatiha, as with any recitation from the Qur'an, by asking for refuge with God from "the accursed devil":[30]

- أَعُوْذُ بِاللهِ مِنَ الشَّـيْطٰنِ الرَّجِيْمِ

- 'aʿūḏu bi-llāhi mina š-šayṭāni r-rajīm.[25]

In the first and second unit, another portion of the Qur'an is recited following the Fatiha.[25] At the end of the recitations one moves to the next position, saying Allahu akbar as one does so.

Bowing (rukūʿ)

Next is bowing from the waist, with palms placed on the knees (according to most schools, women should not bow so low). While bowing, the one praying generally utters formulas of praise under the breath, such as سبحان ربي العظيم (subḥāna rabbīya l-ʿaẓīm "Glory be to my Lord, the Most Magnificent"), thrice or more in odd number of times.[25]

Straightening up (iʿtidāl)

As the worshipper straightens their back they say سمع الله لمن حمده (samiʿa-llāhu li-man ḥamidah, "God hears the one who praises him.")[25] An additional formula of praise is usually uttered under the breath, such as ربنا لك الحمد (rabbanā laka l-ḥamd, "Our Lord, all praise be to you.")[25] After a moment of standing, the worshipper moves to the prostration - again saying Allahu akbar.[25]

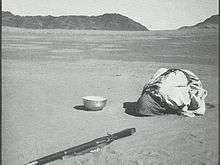

Low bowing/prostration (sujūd)

Then the worshipper kneels and bows low to the ground or prostrates with the forehead, nose, knees, palms and toes touching the floor.[25] The worshipper utters سبحان ربى الأعلى وبحمده (subḥāna rabbiya l-'aʿlā "Glory be to my Lord, the Most High").[25] After a short while in prostration the worshipper very briefly rises to a kneeling position, then returns to the ground a second time. As they rise from the second prostration, they say Allāhu akbar as before.[25] Lifting the head from the second prostration completes the unit.

- If this is the second or last unit, the worshiper proceeds to sitting.

- If not, one returns to a standing position and begins another unit with the Fatiha.

Kneeling/sitting

The worshipper kneels or sits on the ground with legs folded under the body (the precise posture differs between schools), and recites a prayer called the tashahhud.

.jpg)

The tashahhud consists of the testimony of faith (the shahadah) and invoking peace and blessings on Muhammad (salawat). Many schools hold that the right index finger is raised for these prayers.[25] After the tashahhud prayer,

- If there are further units to follow, a new unit is begun by returning to the standing position, uttering the Allahu akbar as before.[25]

- If it is the last unit, the worshipper adds a short supplication called the Ibrahimiyya, which emphasies the relationship between Muhammad and Abraham (Ibrahim), then the salah is then brought to an end as below.

Peace greeting/salutation (taslīm)

Performing the Taslim Reciting the salam facing the right direction Reciting the salam facing the left direction

The worshipper ends the prayer (and exits their state of consecration) by saying السلام عليڪم ورحمة الله (as-salāmu ʿalaykum wa raḥmatu llāh, "Peace and God's mercy be upon you", the taslīm). This is said twice, first to the right and then to the left.[25]

Differences in practice

Muslims believe that Muhammad practiced, taught, and disseminated the worship ritual in the whole community of Muslims and made it part of their life. The practice has, therefore, been concurrently and perpetually practiced by the community in each of the generations. The authority for the basic forms of the salah is neither the hadiths nor the Qur'an, but rather the consensus of Muslims.[32]

This is not inconsistent with another fact that Muslims have shown diversity in their practice since the earliest days of practice, so the salah practiced by one Muslim may differ from another's in minor details. In some cases the Hadith suggest some of this diversity of practice was known of and approved by the Prophet himself.[33]

Most differences arise because of different interpretations of the Islamic legal sources by the different schools of law (madhhabs) in Sunni Islam, and by different legal traditions within Shia Islam. In the case of ritual worship these differences are generally minor, and should rarely cause dispute.[34]

Specific differences

Common differences, which may vary between schools and gender, include:[35][36][37][38][39][40]

- Position of legs and feet.

- Position of hands, including fingers

- Place where eyes should focus

- The minimum amount of recitation

- Loudness of recitation: audible, or moving of lips, or just listening

- Which of the principal elements of the prayer are indispensable, versus recommended, optional, etc.

Shia Muslims, after the end of the prayer, raise their hands three times, reciting Allahu akbar whereas Sunnis look at the left and right shoulder saying taslim. Also, Shias often read "Qunoot" in the second Rakat, while Sunnis usually do this after salah.[41]

A 2015 Pew Research Center study found that women are two percent more likely than men to pray on a daily basis.[42]

Categories

Prayers in Islam are classified into categories based on degrees of obligation. One common classification is fard ("obligatory") & wajib ("compulsory"), and sunnah ("tradition") & nafl ("voluntary").[43]

Mandatory prayers

Five daily prayers

The five daily prayers are obligatory on every Muslim who has reached the age of puberty, with the exception being those who are mentally ill, too physically ill for it to be possible,[44] menstruating,[45] or experiencing postnatal bleeding.[46] Those who are sick or otherwise physically unable to offer their prayers in the traditional form are permitted to offer their prayers while sitting or lying, as they are able.[47]

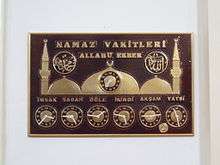

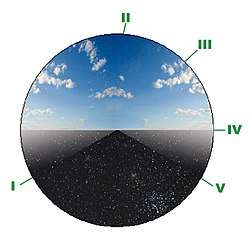

Times of prayers

Each of the five prayers has a prescribed time measured by the movement of the sun. They are: between dawn and sunrise (fajr), after the sun has passed its zenith (zuhr), when afternoon shadows lengthen (asr), just after sunset (maghrib) and around nightfall (isha).[48]

Salah must be prayed in its time unless there is a compelling reason preventing this.[49]

Sunni view

Of the fard category are the five daily prayers, as well as the Friday prayer (Salat al-Jumu'ah), while the Eid prayers and Witr are of the wajib category.[50] Negligence of any of the obligatory prayers renders one a non-Muslim according to the stricter Hanbali madhhab of Sunni Islam, while the other Sunni madhhabs consider doing so a major sin. However, all four madhhabs agree that denial of the mandatory status of these prayers invalidates the faith of those who do so, rendering them non-Muslim. Fard prayers (as with all fard actions) are further classed as either fard al-ayn (obligation of the self) and fard al-kifayah (obligation of sufficiency). Fard al-Ayn are actions considered obligatory on individuals, for which the individual will be held to account if the actions are neglected. Fard al-Kifayah are actions considered obligatory on the Muslim community at large, so that if some people within the community carry it out no Muslim is considered blameworthy, but if no one carries it out, all incur a collective punishment.

Men are required to offer the mandatory salat in congregation (jama'ah), behind an imam when they are able. According to most Islamic scholars, prayer in congregation is mustahabb (recommended) for men, when they are able.[51]

Qasr and jam' bayn as-salaatayn

When travelling over long distances, one may shorten some prayers, a practice known as Qasr. Furthermore, several prayer times may be joined, which is referred to as Jam' bayn as-Salaatayn. Qasr involves shortening the obligatory components of the Zuhr, Asr, and Isha prayers to two rakats.[52] Jam' bayn as-Salaatayn combines the Zuhr and Asr prayers into one prayer offered between noon and sunset, and the Maghrib and Isha prayers into one between sunset and Fajr. Neither Qasr nor Jam' bayn as-Salaatayn can be applied to the Fajr prayer.[53]

Qada

In certain circumstances, one may be unable to offer one's prayer within the prescribed time period (waqt). In this case, the prayer must be offered as soon as one can do so. Several Ahadith narrates that Muhammad stated that permissible reasons to pray Qada Salah are forgetfulness and accidentally sleeping through the prescribed time. However, knowingly sleeping through the prescribed time for Salah is deemed impermissible.[54]

Quranist view

Muslims who reject the Hadith and Quranists, some pray five times and some thrice a day. Quranists in Algeria for example "pray with unlike their usual postures, and do not bow, but believe that prostration is the next posture on completion of recitation (of the Quran)."[55]

Supererogatory prayers

Voluntary prayers

Nafl salah (supererogatory prayers) are voluntary, and one may offer as many as he or she likes almost any time.[56] There are many specific conditions or situations when one may wish to offer nafl prayers. They cannot be offered at sunrise, true noon, or sunset. The prohibition against salah at these times is to prevent the practice of sun worship.[57] Some Muslims offer voluntary prayers immediately before and after the five prescribed prayers. Sunni Muslims classify these prayers as sunnah, while Shi'ah considers them nafil. One schema of the number of rakats for each of the five obligatory prayers as well as the voluntary prayers (before and after) are listed below - once again there are minor differences between schools.[58]

| Name | Prescribed time period (waqt) | Voluntary before fard[t 1] | Obligatory | Voluntary after fard[t 1] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunni | Shi'a | Sunni | Shi'a | |||

| Fajr (فجر) |

Dawn to sunrise, should be read at least 10–15 minutes before sunrise | 2 Rakats Sunnat-Mu'akkadah[t 1] | 2 Rakats[t 1] | 2 Rakats[t 1] | — | 2 Rakats[t 1] |

| Dhur (ظهر) |

After true noon until Asr | 4 Rakats Sunnat-Mu'akkadah[t 2] | 4 Rakats | 4 Rakats[t 3] | 2 Rakats Sunnat-Mu'akkadah[t 2] | 8 Rakats[t 1][t 4][t 5] |

| Asr (عصر) |

Afternoon[t 6][t 7] | 4 Rakats Sunnat-Ghair-Mu'akkdah | 4 Rakats | 4 Rakats | - | 8 Rakats[t 1][t 4][t 5] |

| Maghrib (مغرب) |

After sunset until dusk | 2 Rakats Nafil | 3 Rakats | 3 Rakats | 2 Rakats Sunnat-Mu'akkadah[t 2] | 2 Rakats[t 1][t 4][t 5] |

| Isha (عشاء)[t 8] | Dusk until dawn[t 7] | 4 Rakats Sunnat-Ghair-Mu'akkadah | 4 Rakats | 4 Rakats | 2 Rakats Sunnat-Mu'akkadah,[t 2] 3 Rakats Witr |

2 Rakats[t 1][t 4][t 5] |

Many Sunni Muslims also offer two rakats of nafl salah (supererogatory prayer) after the Zuhr and Maghrib prayers. During the 'Isha prayer, they pray the two rakats of nafl after the two Sunnat-Mu'aqqadah and after the Witr.[58]

Prayers of the tradition

Sun'nah salah are optional and were additional voluntary prayers said by Muhammad. They are of two types: the sunnat mu'aqqaddah (""), practiced on a regular basis, which if abandoned causes the abandoner to be regarded as sinful by the Hanafi School; and the sunnat ghayr mu'aqqaddah (""), practiced on a semi-regular practice by Muhammad, of which abandonment is not considered to be sinful.

Certain sunnah prayers have prescribed waqts associated with them. Those ordained for before each of the fard prayers must be said between the first call to prayer (adhan) and the second call (iqama), which signifies the start of the fard prayer.[59] Those sunnah ordained for after the fard prayers can be said any time between the end of the fard prayers and the end of the current prayer's waqt.[59] Any amount of extra rakats may be offered, but most madha'ib prescribe a certain number of rakats for each sunnah salah.

Types

Friday prayer (Jumu'ah)

Salat al-Jumu'ah is a congregational prayer on Friday, which replaces the Zuhr prayer. It is compulsory upon men to pray this in congregation, while women may pray it so or offer Zuhr salat instead.[60] Salat al-Jumu'ah consists of a sermon (khutba) given by the sermoner (khatib), after which two rakats are prayed.[61] There is no Salat al-Jumu'ah without a khutba. Khutba is supposed to be carefully listened to as it replaces Sawaab of two Rakats.[62]

| Name | Prescribed time period (waqt) | Voluntary before fard | Obligatory | Voluntary after fard | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunni | Shi'a | Sunni | Shi'a | |||

| Jumu'ah (جمعة) |

After true noon until Asr | 4 Rakats Sunnat-e-Mu'akkadah | 2 Rakats Sunnat/ Mustahab | 2 Rakats Furz | 4 Rakats Sunnat Mu'akkadah

2 Rakats Sunnat Mu'akkadah 2 Rakats Nafil |

2 Rakats Sunnat Mu'akkadah |

Nightly prayers

The time for nightly prayers (Salat al-Layl) starts after midnight until the time for Fajr prayer.[63] It is considered highly meritorious by all Shia Muslims, and is said to bring numerous benefits to the believer, mainly gaining proximity to Allah.[64] Layl prayer includs eleven Rakat:[63]

- Tahajjud Prayer (Nafilah of Layl): 8 Rakat consist of 4 prayers 2 Rakat.

- al-Shafa prayer (Salat al-Shafa): 2 Rakat.

- Witr prayer (Salat-al-Witr): 1 Rakat.

Tahajjud

The word tahajjud is derived from the root H-J-D (هجد) meaning "spending the night awake or asleep".[65] This prayer is not obligatory. The time for tahajjud (nightly prayers) is started from the late hours of the night and is finished when the time for Fajr prayer entered. The prayer includes eight rakat, followed by three rakat of Witr prayer.[66]

Witr

The word witr (وتر) means "odd number" as an adjective and "string" or "chord" as a noun. Witr is offered after the salah of 'Isha. Some Muslims consider witr compulsory while others consider it supererogatory. It may contain an odd number of rakats from one to five according to the different schools of jurisprudence. Witr is most commonly offered in three rakats, actually one raka'ah added to two rakat of Tahajjud or Tarawih prayer at the end.[67] The prayer usually includes the qunut.[64]

Prayers of Eid

The salah of the 'Idayn is said on the mornings of 'Id al-Fitr and 'Id an-Nahr. The Eid prayer is classified by some as fard, likely an individual obligation (fard al-ayn) though some Islamic scholars argue it is only a collective obligation (fard al-kifayah).[68] It consists of two rakats, with seven (or three for the followers Imam Hanafi) takbirs offered before the start of the first rakat and five (or three for the followers of Imam Hanafi) before the second. After the salah is completed, a sermon (khutbah) is offered. However, the khutbah is not an integral part of the Eid salah.[69] The Eid salah must be offered between sunrise and true noon i.e. between the time periods for Fajr and Zuhr.[52]

Prayer of Istikhaarah

The word istikharah is derived from the root ḵ-y-r (خير) "well-being, goodness, choice, selection".[70] Salat al-Istikhaarah is a prayer offered when a Muslim needs guidance on a particular matter. To say this salah one should pray two rakats of non-obligatory salah to completion. After completion one should request God that which on is better.[52] The intention for the salah should be in one's heart to pray two rakats of salah followed by Istikhaarah. The salah can be offered at any of the times where salah is not forbidden.[71]

Tahiyyat al-Masjid

Upon entering the mosque, Tahiyyat al-Masjid ("mosque greeting" prayer) may be offered; this is to pay respects to the mosque. Every Muslim entering the mosque is encouraged to offer these two rakats.[72]

Prayer in congregation

Prayer in the congregation (jama'ah) is considered to have more social and spiritual benefits than praying by oneself.[73] When praying in congregation, the people stand in straight parallel rows behind one person who conducts the prayer, called imam, also called the ‘leader’. The imam must be above the rest in knowledge, action, piety, and justness and possess faith and commitment the people trust, Balanced Perception of Religion and the best knowledge of the Qur'an.[54] The prayer is offered as normal, with the congregation following the imam in order as he/she offers the salah.[74]

Standing arrangement

For two people of the same gender, the imam would stand on the left, and the other person is on the right. For more than two people, the imam stands one row ahead of the rest.

When the Worshippers consist of men and women combined, a man is chosen as the imam. In this situation, women are typically forbidden from assuming this role. This point, though unanimously agreed on by the major schools of Islam, is disputed by some groups, based partly on a hadith whose interpretation is controversial. When the congregation consists entirely of women and pre-pubescent children, one woman is chosen as imam.[75] When men, women, and children are praying, the children's rows are usually between the men's and women's rows, with the men at the front and women at the back. Another configuration is where the men's and women's rows are side by side, separated by a curtain or other barrier,[76] with the primary intention being for there to be no direct line of sight between male and female Worshippers, following a Qur'anic injunction toward men and women each lowering their gazes (Qur'an 24:30–31).[77]

Notes

Table notes

- According to Shia Muslims, these are to be said in two and two rakats (four in total). This is not the case for Sunni Muslims.

- According to Sunni Muslims, there is a difference between Sunnat-Mu'akkadah (obligatory) and Sunnat-Ghair-Mu'akkadah (voluntary). Unlike for the Sunnat-Ghair-Mu'akkadah, the Sunnat-Mu'akkadah was prayed by Muhammed daily.

- Replaced by Jumu'ah on Fridays, which consists of two rakats.

- Mustahab (praiseworthy) to do everyday. (Shias)

- According to Shia Muslims, this prayer is termed nawafil.

- According to Imam Abu Hanifa, "Asr starts when the shadow of an object becomes twice its height (plus the length of its shadow at the start time of Zuhr)." For the rest of Imams, "Asr starts when the shadow of an object becomes equal to its length (plus the length of its shadow at the start time of Zuhr)." Asr ends as the sun begins to set.

- According to Shia Muslims, Asr prayer and Isha prayer have no set times but are said any time starting from midday. Zuhr and Asr prayers must be offered before sunset, and the time for Asr starts after Zuhr has been prayed. Maghrib and Isha prayers must be offered before midnight, and the time for Isha prayer can start after Maghrib has been prayed, as long as no more light remains in the western sky signifying the arrival of the true night.

- Further information on the usage of the word "Isha" (evening) see Quran 12:16, Quran 79:46

References

- Lane, Edward William (1968). An Arabic-English Lexicon. Beirut, Lebanon: Librairie du Liban. p. 1721. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- FARRAKHAN, Mahmoud Reza; AREFIAN, Abdulhamid; JAHROMI, Gholmreza Saber. A Reanalysis of Social - Cultural Impacts and Functions of Worship: A Case Study on Salah (Namaz). Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, [S.l.], v. 7, n. 4 S1, p. 249, jul. 2016. ISSN 2039-2117. Available at: <https://www.mcser.org/journal/index.php/mjss/article/view/9408>. Date accessed: 20 Mar. 2020.

- The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. "Salat". oxfordislamicstudies.

- Chittick, William C.; Murata, Sachiko (1994). The vision of Islam. Paragon House. ISBN 9781557785169.

- http://ejtaal.net/aa/#hw4=h624,ll=1767,ls=5,la=2489,sg=609,ha=416,br=558,pr=93,aan=339,mgf=520,vi=227,kz=1375,mr=366,mn=792,uqw=941,umr=618,ums=519,umj=464,ulq=1090,uqa=251,uqq=197,bdw=h527,amr=h372,asb=h556,auh=h901,dhq=h321,mht=h522,msb=h139,tla=h66,amj=h455,ens=h873,mis=h1243

- "NAMĀZ". doi:10.1163/_eifo_dum_2947. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - B. Morris, Andrew. Catholic Education: Universal Principles, Locally Applied. ISBN 978-1-4438-3634-0.

- YOUSOF, GHULAM-SARWAR. One Hundred and One Things Malay. Partridge Publishing Singapore. ISBN 9781482855340.

- Dukes, Kais, ed. (2009–2017). "Quran Dictionary". Quranic Arabic Corpus. Retrieved 26 October 2019.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- "how many times is salat repeated in Quran?". Fars news. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- Muhammad, Farooq-i-Azam Malik. What is Islam Who are the Muslims?. Institute of Islamic Knowledge (2008). ISBN 978-0981943909.

- Makarem Shirazi , Subhani, Ayatullah Naser, Ayatullah Jafar. "Philosophy of Islamic Laws". Islamic Seminary Publications.

- BIN SAAD, ADEL. A COMPREHENSIVE DISCRIPTION OF THE PROPHET'S WAY OF PRAYER: صفة صلاة النبي. ISBN 978-2745167804.

- From Surah al-Mu’minun (23) to Surah al-Furqan (25) verse 20. "An Enlightening Commentary into the Light of the Holy Qur'an vol. 11". Imam Ali Foundation.

- Sheihul Mufliheen (October 2012). Holy Quran's Judgement. XLIBRIS. p. 57. ISBN 978-1479724550.

- Elias, Abu Amina (25 June 2015). "The purpose of prayer in Islam | Faith in Allah الإيمان بالله". Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Multicultural Handbook of Food, Nutrition, and Dietetics, p. 43, Aruna Thaker, Arlene Barton, 2012

- Ramzy, Sheikh (23 July 2012). The Complete Guide to Islamic Prayer (Salāh). AuthorHouseUK. ISBN 978-1477214640.

- Ismail Kamus (1993). Hidup Bertaqwa (2nd ed.). Kuala Lumpur: At Tafkir Enterprise. ISBN 983-99902-0-9.

- Salīm, ʻamr ʻabd al-Munʻim (2005). Amr ʻAbd al-Munʻim Salīm, Important lessons for Muslim women, Darussalam, 2005, page 174. ISBN 9789960732350. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- "Women In Islam Versus Women In The Judaeo-Christian Tradition". twf.org. Archived from the original on 8 September 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- "Rules of Salat (Part III of III)". Al-Islam.org. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- Abu Maryam (translator). "The Prostration of Forgetfulness : Shaikh 'Abdullaah bin Saalih Al-'Ubaylaan". AbdurRahman.Org. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- "Ruling on uttering the intention (niyyah) in acts of worship - Islam Question & Answer". islamqa.info. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Haddad, Yvonne Yazbeck; Smith, Jane I. (1 January 2014). The Oxford Handbook of American Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780199862634.

- Ciaravino, Helene (2001). How to Pray: Tapping Into the Power of Divine Communication. Square One Publishers (2001). p. 137. ISBN 9780757000126.

- Al-Tusi, Muhammad Ibn Hasan. Concise Description of Islamic Law and Legal Opinions. Islamic College for Advanced Studie; UK ed. edition (October 1, 2008). pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-1904063292.

- Muhammad Ali, Maulana. Religion of Islam. Ahmadiyya Anjuman Ishaat; Sixth Revised Edition edition (June 1989). pp. 306–310. ISBN 978-0913321324.

- Isfahani, Ayatullah Mirza Mahdi. "Salat (Prayer): The Mode of Divine Proximity and Recognition".

- Shenk, David W. Journeys Of The Muslim Nation and the Christian Church: Exploring the Mission of Two Communities (Christians Meeting Muslims). Herald Press (October 12, 2003). pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-0836192520.

- al-Hassani, Abu Qanit (2009). The Guiding Helper: Main Text and Explanatory Notes. p. 123.

- Al-Mawrid Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Muhammad al-Bukhari. "Sahih al-Bukhari, Book of military expeditions". Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Abdal Hakim Murad. "Understanding the Four Madhhabs". Archived from the original on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "Share Islam" (PDF). islamtomorrow.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- "Page Title". haqqaninaqshbandiuk.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- "eShaykh: Salat Guide for Shafi'i". Google Docs. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- "Salat According to Shafii Fiqh". sunnah.org. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- "SALAH ACCORDING TO THE HANBALI SCHOOL OF THOUGHT". daruliftabirmingham.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- "Imam Ali Foundation - London". najaf.org. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- "Shia praying differences". shiastudies.org. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Swanson, Ana (30 March 2016). "Why women are more religious than men". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- "Understanding Salat" Archived 28 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine from Albalagh

- Elshabrawy , Hassanein, Elsayed, Ahmad. Inclusion, Disability and Culture (Studies in Inclusive Education). Sense Publishers (November 28, 2014). pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-9462099227.

- GhaneaBassiri, Kambiz. Competing Visions of Islam in the United States: A Study of Los Angeles. Praeger (July 30, 1997).

- Kuscular, Remzi. Cleanliness In Islam. Tughra Books; 1st English Ed edition (January 1, 2008). ISBN 978-1597841207.

- Turner, Colin. Islam: The Basics. Routledge; 2nd edition (May 24, 2011). pp. 106–108. ISBN 978-0415584920.

- "Salat". Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "Laws and Practices: How to Perform the Daily Prayers".

- Schade, Johannes. Encyclopedia of World Religions. Mars Media/Foreign Media (January 9, 2007). ISBN 978-1601360007.

- "Rules of Salat (Part III of III)". Al-Islam.org. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Buyukcelebi, Ismail. Living in the Shade of Islam. Tughra (March 1, 2005). ISBN 978-1932099867.

- Sharaf al-Din al-Musawi, Sayyid Abd al-Husayn. "Combining The Two Prayers". Hydery Canada Ltd.

- Qara'ati, Muhsin. "The Radiance of the Secrets of Prayer". Ahlul Bayt World Assembly.

- "صحف: فتوى سعودية بقتل الإسرائيليين.. وانتشار "القرآنيين"" [Newspapers: Saudi fatwa to kill Israelis ... and the spread of "Quranists"]. CNN Arabic. Time Warner Company. 26 January 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- "prayers". islamicsupremecouncil.com. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- Ringwald, Christopher D. A Day Apart: How Jews, Christians, and Muslims Find Faith, Freedom, and Joy on the Sabbath. Oxford University Press (January 8, 2007). pp. 117–119. ISBN 978-0195165364.

- "A Shi'ite Encyclopedia". Ahlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library Project.

- "Virtue and times of regular Sunnah prayers (Sunnah mu'akkadah) - islamqa.info". islamqa.info. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- Fahd Salem Bahammam. The Muslim's Prayer. Modern Guide. ISBN 9781909322950. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- Akhtar Rizvi, Sayyid Saeed (1989). Elements of Islamic Studies. Bilal Muslim Mission of Tanzania.

- Margoliouth, G. (2003). "Sabbath (Muhammadan)". In Hastings, James (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. 20. Selbie, John A., contrib. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 893–894. ISBN 978-0-7661-3698-4.

- Kassamali, Kassamali, Tahera , Hasnain. "Salatul Layl". Tayyiba Publishers & Distributors.

- Majlisi, Muhammad Baqir. "Salat al-Layl". Al-Fath Al-Mubin Publications.

- Muhammad Ali, Maulana. Religion of Islam. Ahmadiyya Anjuman Ishaat; Sixth Revised Edition edition (June 1989). ISBN 978-0913321324.

- Islam International Publications. Salat: The Muslim prayer book. Islam International Publishers (1997). ISBN 978-1853725463.

- Ubaida, Abu. "How to pray the witr prayer".

- "Ruling on Eid prayers". Islam Question and Answer. Archived from the original on 24 October 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- "Islam Today". Archived from the original on 17 October 2007.

- Nieuwkerk, Karin van. Performing Piety: Singers and Actors in Egypt's Islamic Revival. University of Texas Press; Reprint edition (October 1, 2013). ISBN 9780292745865.

- Iṣlāhī, Muḥammad Yūsuf. "Etiquettes of Life in Islam".

- Firdaus Mediapro, Jannah. The Path to Islamic Prayer English Edition Standar Version. Blurb (October 18, 2019). ISBN 978-1714100736.

- Qara ati, Muhsin. The Radiance of the Secrets of Prayer. ISBN 978-1496053961.

- Hussain, Musharraf. The Five Pillars of Islam: Laying the Foundations of Divine Love and Service to Humanity. Kube Publishing Ltd (October 10, 2012). pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-1847740540.

- "Iranian women to lead prayers". BBC. 1 August 2000. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- Cornell, Vincent J. Voices of Islam: Voices of life : family, home, and society. Praeger Publishers; 1st edition (January 1, 2007). pp. 25–28. ISBN 978-0275987350.

- Maghniyyah, Muhammad Jawad. "Prayer (Salat), According to the Five Islamic Schools of Law". Islamic Culture and Relations Organisation.

Further reading

- Smith, Jane I.; Haddad, Yvonne Yazbeck (1993). The Oxford Handbook of American Islam (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 162–163.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salat. |

.jpg)