Psychology in medieval Islam

Islamic psychology or ʿilm al-nafs[1] (Arabic: علم النفس), the science of the nafs ("self" or "psyche"),[2] is the medical and philosophical study of the psyche from an Islamic perspective and addresses topics in psychology, neuroscience, philosophy of mind, and psychiatry as well as psychosomatic medicine.

Concepts from Islamic thought have been reexamined by Muslim psychologists and scholars in the 20th and 21st centuries.[3]

Terminology

In the writings of Muslim scholars, the term Nafs (self or soul) was used to denote individual personality and the term fitrah for human nature. Nafs encompassed a broad range of faculties including the qalb (heart), the ruh (spirit), the aql (intellect) and irada (will). Muslim scholarship was strongly influenced by Greek and Indian philosophy as well as by the study of scripture, drawing particularly from Galen' understanding of the four humors of the body.

In medieval Islamic medicine in particular, the study of mental illness was a speciality of its own,[4] and was variously known as al-‘ilaj al-nafs (approximately "curing/treatment of the ideas/soul/vegetative mind),[5] al-tibb al-ruhani ("the healing of the spirit," or "spiritual health") and tibb al-qalb ("healing of the heart/self," or "mental medicine").[2]

The Classical Arabic term for the mentally ill was "majnoon" which is derived from the term "Jenna", which means "covered". It was originally thought that mentally ill individuals could not differentiate between the real and the unreal. However, due to their nuanced nature treatment on the mentally ill could not be generalized as it was in medieval Europe [6] This term was gradually redefined among the educated, and was defined by Avicenna as "one who suffers from a condition in which reality is replaced with fantasy".

Ethics and theology

In the Islamic world, special legal protections were given to the mentally ill. This attitude was reinforced by scripture, as exemplified in Sura 4:5 of the Qur'an:

Do not give your property which God assigned you to manage to the insane: but feed and clothe the insane with this property and tell splendid words to them.

— "[4]

This Quranic verse summarized Islam's attitudes towards the mentally ill, who were considered unfit to manage property but must be treated humanely and be kept under care by either a guardian or the state.[4]

This belief was similar to that of modern psychology, specifically to Sigmund Freud's beliefs that the mentally ill require help and treatment, as opposed to how society dealt with the mentally ill before modern psychology.

Major contributors

Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi

Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (865 – 925), known as Rhazes in the western tradition, was an influential Persian physician, philosopher, and scientist during the Golden Age of Islam, and among the first in the world to write on mental illness and psychotherapy.[7] As chief physician of Baghdad hospital, he was also the director of one of the first psychiatric wards in the world. Two of his works in particular, El-Mansuri and Al-Hawi, provide descriptions and treatments for mental illnesses.[7]

Abu-Ali al-Husayn ibn Abdalah ibn-Sina

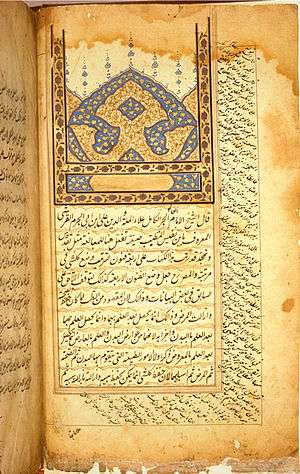

Abu-Ali al-Husayn ibn Abdalah ibn-Sina (980-1030), known to the west as Avicenna, was a Persian polymath who is widely regarded for his writings on such diverse subjects as philosophy, physics, medicine, mathematics, geology, Islamic theology, and poetry. In his most widely celebrated work, the Canon of Medicine (Al-Qanun-fi-il-Tabb), he provided descriptions and treatments for such conditions as insomnia, mania, vertigo, paralysis, stroke, epilepsy, and depression as well as male sexual dysfunction. He was a pioneer in the field of psychosomatic medicine, linking changes in mental state to changes in the body.[8]

Mental healthcare

The earliest bimaristans were built in the 9th century, and large bimaristans built in the 13th century contained separate wards for mentally ill patients.[9]

Treatment of mental illness

In addition to medication, treatment for mental illness might include baths, music, and occupational therapy reflecting the great emphasis placed on the relationship between illness of the mind and problems in the body. Medicine would be prescribed in order to re-balance the four humors of the body, an imbalance of which might result in psychosis.[8] Insomnia, for example, was thought to result from excessive amounts of the dry humors which could be remedied by the use of humectants.

See also

- Islamic philosophy

- Medicine in the medieval Islamic world

- Ophthalmology in medieval Islam

- Science in medieval Islam

- Sufi psychology

Notes

- (Haque 2004, p. 358)

- Deuraseh, Nurdeen; Mansor Abu, Talib (2005), "Mental health in Islamic medical tradition", The International Medical Journal, 4 (2): 76–79.

- (Haque 2004)

- (Youssef, Youssef & Dening 1996, p. 58)

- (Haque 2004, p. 376)

- Okasha, A. (2001), "Egyptian Contribution to the Conception of Mental Health", Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 7 (3): 377–380.

- Wael Mohamed, C.R. (2012). "Arab and Muslim Contributions to Modern Neuroscience". International Brain Research Organization History of Neuroscience.

- A. Okasha, C.R. (1). "Mental Health and Psychiatry in the Middle East". Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 7: 336–347. Check date values in:

|date=, |year= / |date= mismatch(help) - Miller, Andrew C (December 2006). "Jundi-Shapur, bimaristans, and the rise of academic medical centres". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 99 (12). pp. 615–617. doi:10.1258/jrsm.99.12.615. Archived from the original on 2013-02-01. Retrieved 2018-08-26.

References

- Bakhtiar, Laleh (2019), Quranic Psychology of the Self: A Textbook on Islamic Moral Psychology (ilm al-nafs), Kazi Publications, ISBN 1567446418

- Haque, Amber (2004), "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists", Journal of Religion and Health, 43 (4): 357–377, doi:10.1007/s10943-004-4302-z

- Plott, C. (2000), Global History of Philosophy: The Period of Scholasticism, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0551-8

- Youssef, Hanafy A.; Youssef, Fatma A.; Dening, T. R. (1996), "Evidence for the existence of schizophrenia in medieval Islamic society", History of Psychiatry, 7 (25): 55–62, doi:10.1177/0957154X9600702503, PMID 11609215