Richmond–San Rafael Bridge

The Richmond–San Rafael Bridge (also officially named the John F. McCarthy Memorial Bridge[3]) is the northernmost of the east–west crossings of the San Francisco Bay in California, USA. Officially named after California State Senator John F. McCarthy, it bridges Interstate 580 from Richmond on the east to San Rafael on the west. It opened in 1956, replacing ferry service by the Richmond–San Rafael Ferry Company.[4]

Richmond–San Rafael Bridge | |

|---|---|

The Richmond–San Rafael Bridge from its western terminus | |

| Coordinates | 37.9347°N 122.4338°W |

| Carries | 5 lanes (2 WB on upper level, 2-3 EB on lower) of |

| Crosses | San Francisco Bay and San Pablo Bay |

| Locale | San Rafael, California and Richmond, California |

| Official name | Richmond–San Rafael Bridge or John F. McCarthy Memorial Bridge |

| Other name(s) | Richmond Bridge San Rafael Bridge |

| Named for | John F. McCarthy |

| Owner | State of California |

| Maintained by | California Department of Transportation and the Bay Area Toll Authority |

| ID number | 28 0100 |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Double-Decked Dual Cantilever bridge with Pratt Truss Approach |

| Total length | 29,040 ft (5.500 mi; 8.85 km) |

| Longest span | 1,070 feet (330 m) cantilever structure |

| No. of spans | 77 in total, consisting of: 19 girder spans (west) |

| Piers in water | 70[1] |

| Clearance below | 185 feet (56 m) (main channel) 135 feet (41 m) (secondary channel) |

| History | |

| Designer | Norman Raab |

| Constructed by | Gerwick—Kiewit Joint Venture (substructure) Kiewit—Soda—Judson Pacific-Murphy Joint Venture (superstructure) |

| Construction start | March 1953 |

| Construction cost | US$62,000,000 (equivalent to $583,000,000 in 2019) |

| Opened | September 1, 1956 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 66,800 (2011) 67,800 (2012) |

| Toll | Cars (westbound only) $6.00 (cash or FasTrak), $3.00 (carpools during peak hours, FasTrak only) |

| |

| Interactive map highlighting the Richmond–San Rafael Bridge | |

History

Early proposals

Proposals for a bridge were advanced in the 1920s, preceding the completion of the Golden Gate Bridge. In 1927, Roy O. Long of The Richmond–San Rafael Bridge, Incorporated, applied for a franchise to construct and operate a private toll bridge. The proposed 1927 Long bridge would have been a steel suspension bridge, carrying a 30-foot-wide (9.1 m) roadway for a distance of 14,600 feet (4,500 m) at an estimated construction cost of US$12,000,000 (equivalent to $176,600,000 in 2019). The bridge would afford a maximum vertical clearance of 135 feet (41 m) with a 1,200-foot (370 m) main span.[5] Charles Derleth, Jr. was selected as the consulting engineer, after having served in that role for the recently completed Carquinez Bridge.[6] The Long bridge would have spanned San Pablo Bay between Point Orient (in Contra Costa County) to just below McNear's Point (in Marin County), and Long was granted the franchise in February 1928 by the Contra Costa County Board of Supervisors.[7]

A competing proposed bridge also came out in 1927, from Charles Van Damme of the Richmond-San Rafael Ferry Company. The 1927 Van Damme bridge would have carried a 27-foot-wide (8.2 m) roadway for a distance of 19,000 feet (5,800 m) at an identical estimated construction cost of US$12,000,000 (equivalent to $176,600,000 in 2019).[8] It would have spanned San Pablo Bay from Castro Point (Contra Costa County) to Point San Quentin (Marin County), approximately the same routing as the eventually completed 1956 bridge.[7] Although the 1927 Long bridge had been granted a franchise in February 1928, Van Damme subsequently petitioned to reopen the case, since the ferry company owned the land at the proposed eastern terminus and therefore should have been favored in the franchise selection process.[9] Also, since the ferry company's franchise rights were not set to expire until the 1950s, Long's 1927 bridge cost would have increased to reimburse losses to ferry revenues.[8] Soon after winning the franchise rights, Long approached Van Damme with an offer to buy the Richmond-San Rafael Ferry Company for US$1,250,000 (equivalent to $18,600,000 in 2019).[10]

Van Damme and Long later agreed in September 1928 to merge their interests for a combined bridge proposal between Point San Pablo (Contra Costa County) and McNear's Point (Marin County).[11] The combined project, now headed by Oscar Klatt for the American Toll Bridge Company, received approval for the routing from then-Secretary of War Good in May 1929, although vertical and horizontal clearances for the proposed bridge were not fully established at the time.[12] In November 1929, vertical clearance had been increased to 160 feet (49 m) to satisfy Navy requirements.[13] The construction permit was issued in February 1930.[14]

Klatt's 1929 bridge was dormant for nearly a decade following the issuance of a construction permit in 1930. An extension was filed in 1938 to allow construction to start as late as February 1942,[15] and fresh plans for a bridge district to facilitate financing were announced in 1939.[16] In 1947, interest was revived in bridging Marin and Contra Costa Counties.[17]

Tomasini's San Francisco–Alameda–Marin crossings

A third bridge was proposed in late 1927 by the enigmatic T.A. Tomasini.[18] Tomasini's 1927 bridge called for two lanes of automobile traffic straddling a central rail line from San Pedro Hill (Marin) to San Pablo station (Contra Costa), a distance of over 5 miles (8.0 km).[19] In 1928, Tomasini presented a revised proposal for a bridge farther south than the other two bridges—spanning the water from Albany (in Alameda County) to Tiburon. The 1928 Tomasini Albany–Tiburon bridge was the longest of the three proposed bridges by a significant margin.[9][20] The proposed Albany–Tiburon bridge would have been similar in concept to the 1967 San Mateo–Hayward Bridge, with a high-level western section approximately 7,700 feet (2,300 m) long transitioning to a low-level eastern causeway. The western section featured two 1,000-foot-wide (300 m) spans to cross the navigation channels, with the western navigation span having a minimum vertical clearance of 150 feet (46 m) and the eastern navigation span having a minimum vertical clearance of 135 feet (41 m).[21] The 1,000-foot-wide (300 m) navigation channels for the proposed Albany–Tiburon bridge were opposed by shipping interests, who wanted the channels to be 1,500 feet (460 m) wide instead. The cost of the longer spans required would have made the proposed Albany–Tiburon bridge impractical, and Tomasini argued that "any mariner who could not negotiate a bridge such as proposed should lose his license."[22]

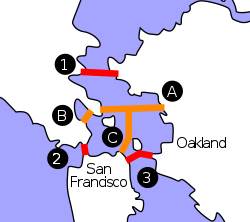

- Albany–Tiburon bridge

- Sausalito–Belvedere bridge

- San Francisco–Marin–Alameda tunnel & bridge

Tomasini would later add a bridge spanning Richardson Bay in March 1928 from Sausalito to Belvedere to his proposal.[11] The additional Sausalito–Belvedere bridge would have been 7,300 feet (2,200 m) long and 22 feet (6.7 m) wide with a lift span to allow the passage of large vessels, at an estimated cost of US$750,000 (equivalent to $11,200,000 in 2019).[23][24] Meanwhile, in April 1928 Tomasini recruited the prominent Ralph Modjeski to serve as the consulting head engineer for the proposed Albany–Tiburon span,[25] and Modjeski promptly complimented the plans that had been drawn up by Tomasini's chief engineer, Erle L. Cope.[24] The design for a lift span in the proposed Sausalito–Belvedere bridge was changed to a bascule after public comments were received from a local shipbuilder.[26] Tomasini received a permit for the Sausalito–Belvedere bridge from the War Department in December 1928.[27] Tomasini had planned to commence construction of the Sausalito–Belvedere bridge in July 1930,[28] but he was met with opposition from the Tiburon-Belvedere Chamber of Commerce, who felt the creation of a bridge would eliminate the promised San Francisco-Tiburon ferry service.[29] In 1931, the Richardson Bay Redwood Bridge was opened, which was the largest structure in the world constructed of redwood.[30] The Redwood Bridge carried the Redwood Highway (present-day US 101) and spanned the upper reach of Richardson Bay,[31] eliminating some of the need for the proposed Sausalito–Belvedere bridge. The Redwood Bridge would be replaced by a concrete structure in the 1950s.[32]

Tomasini continued to add to the project scope in July 1928 by proposing a bridge and tunnel to join San Francisco to the proposed Albany–Tiburon bridge. The tunnel would run roughly northeast from Bay Street and Grant Avenue, not far from present-day Pier 39, at a depth of 50 feet (15 m) below low tide water level for 11,200 feet (3,400 m). At that point, the tunnel would surface northwest of Goat Island, and then transition to a bridge nearly 4 miles (6.4 km) long with a minimum vertical clearance of 50 feet (15 m) and two lift spans connecting to the proposed Albany–Tiburon bridge. The cost of the entire project was US$55,670,000 (equivalent to $828,900,000 in 2019), split as US$20,000,000 (equivalent to $297,800,000 in 2019) for the Albany–Tiburon bridge, US$670,000 (equivalent to $10,000,000 in 2019) for the Sausalito–Belvedere bridge, and US$35,000,000 (equivalent to $521,100,000 in 2019) for the San Francisco–Marin–Alameda tunnel and bridge.[33] Tomasini organized each of the three proposed structures as independent projects, preferably to be built simultaneously, but in the event that one was not approved, it would not delay the construction of the other two.[33] San Francisco's board of supervisors rejected Tomasini's San Francisco–Marin–Alameda tunnel and bridge in September 1928, although the board's action was non-binding.[21]

By February 1932, Tomasini's proposed Albany–Tiburon bridge had changed to a combination bridge—tunnel. The bridge portion was a low trestle approximately 19,800 feet (6,000 m) long, extending westward from Point Fleming in Albany in Alameda County. The proposed tunnel would have been 17,200 feet (5,200 m) long and ventilated by four towers, emerging at Bluff Point near Tiburon in Marin County.[34] Total estimated cost for the two structures was now US$35,000,000 (equivalent to $655,900,000 in 2019) and despite opposition from the US Navy, who cited potential navigation hazards,[35] the bridge—tunnel was approved by the War Department in July 1932.[34] Although he had the permit to begin work, Tomasini filed numerous annual extensions to retain the rights through 1941,[36] apparently due to a lack of funding to start work. Tomasini was still scrambling for funding in August 1941, seeking the issue of bonds worth US$20,000,000 (equivalent to $347,600,000 in 2019).[37] Tomasini lost the rights to the crossing in October 1941,[38] which was not the first time he was opposed by Earl Warren, who had questioned the validity of Tomasini's franchise as early as 1933.[39] Still, Tomasini was doggedly trying to advance his plans as late as 1948.[40]

Construction: 1953–1956

In 1949, the County of Marin and the City of Richmond commissioned a preliminary engineering report from Earl and Wright of San Francisco, which concluded that a bridge would be feasible.[41] A follow-up 1950 study, conducted by the Division of San Francisco Bay Toll Crossings, was commissioned by Marin County and the City of Richmond using US$200,000 (equivalent to $2,130,000 in 2019) in state funding. The 1950 report concluded the bridge could be built in accordance with the California Toll Bridge Authority Act.[41] The preliminary design was approved on 1951-08-08 and California approved the preliminary report on 1951-11-27. The California Toll Bridge Authority authorized the issue of US$72,000,000 (equivalent to $693,200,000 in 2019) in bonds on 1952-11-07 and subsequently sold US$62,000,000 (equivalent to $592,500,000 in 2019) on 1953-02-26 to construct a single-deck bridge. The remaining US$10,000,000 (equivalent to $95,600,000 in 2019) was reserved for construction contingencies and to complete the lower deck of the bridge.[42] The $62 million raised from bond sales was divided into three parts: US$50,000,000 (equivalent to $477,800,000 in 2019) for construction, US$10,000,000 (equivalent to $95,600,000 in 2019) to address interest obligations on the bonds during the construction period, and US$2,000,000 (equivalent to $19,100,000 in 2019) in construction contingency.[42] In 1954, Governor Knight declared the second deck should not be delayed in the public interest, and US$6,000,000 (equivalent to $57,300,000 in 2019) was loaned from the State School Land Fund in 1955 to complete the second deck. The bridge was finished $4 million under budget.[43]

During the study period, an earth and rock-fill bridge with lift structures was considered, but the high-level bridge was chosen as the cost of a low bridge with navigation locks and lifting structures was prohibitive.[41]

The majority of construction costs were tied up in two contracts that opened for bidding on 1952-12-19. The first contract, for the substructure, was awarded to the low bidder, the Ben C. Gerwick, Inc. — Peter Kiewit Sons' Co. Joint Venture for US$14,234,550 (equivalent to $136,000,000 in 2019). The second contract, for the superstructure, was awarded to the low bid of US$21,099,319 (equivalent to $201,600,000 in 2019) by a joint venture between Peter Kiewit Sons' Co. — A. Soda & Son — Judson Pacific Murphy Corp.[41] The substructure construction moved rapidly, with an estimated 45% of piers completed approximately a year after the contract was awarded.[1]

At the time the bridge was completed, it was hailed as the world's second-longest bridge, behind the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge[44] and the longest continuous steel bridge.[45]

Historical notes

Originally a part of State Route 17, the bridge is now part of Interstate 580.

Upon its opening, the Richmond–San Rafael bridge was the last bridge across San Francisco Bay to replace a previous ferry service, leaving the Benicia–Martinez Ferry across Carquinez Strait as the only remaining auto ferry in the Bay Area (it would be replaced by a bridge in 1962).

Description

The bridge—including approaches—measures 5.5 miles (29,040 feet / 8,851.39 m / 8.9 km) long. At the time it was built, it was one of the world's longest bridges. The bridge spans two ship channels and has two separate main cantilever spans. Both main cantilever spans are raised to allow ship traffic to pass, and in between, there is a "dip" in the elevation of the center section,[46] giving the bridge a vertical undulation or "roller coaster" appearance and also the nickname "roller coaster span". To save money, the cantilever main spans share identical symmetric designs, so the "uphill" grade on the approach required for the elevated span is duplicated on the other "downhill" side, resulting in a depressed center truss section.[47] In addition, because the navigation channels are not parallel to each other, the bridge also does not follow a straight line.[48] This appearance has also been referred to as a "bent coat hanger".[43]

After it was completed, many were disappointed by the aesthetics of the low budget bridge,[49] including Frank Lloyd Wright, who reportedly called for its destruction[50] and called it "the most awful thing I've ever seen" in 1953, during its construction.[51] The neighboring Golden Gate Bridge and the western span of Bay Bridge were considered engineering and historical marvels, and the Richmond–San Rafael Bridge was not considered in the same class. However, the senior engineers for the Richmond–San Rafael Bridge were the same engineers that worked on the Bay Bridge[52] and the resulting design echoed the lessons learned from the eastern span of the Bay Bridge.[53]

From west (Point San Quentin) to east (Castro Point), the bridge consists of:[54][1]

- A 2,845-foot (867 m) trestle structure supported by fifty-seven bents. The upper deck is 2,845 feet (867 m), and the lower deck is slightly longer at 3,635 feet (1,108 m).

- 1,900 feet (580 m) of girder spans, consisting of nineteen 100-foot (30 m) girder spans

- 4,125 feet (1,257 m) of truss spans, divided into fourteen trusses each 292 feet (89 m) long, on average.

- The western 2,145-foot (654 m) cantilever structure, with arms measuring 538 feet (164 m) each flanking a central span of 1,070 feet (330 m). The western cantilever span is the main 1,070-foot-wide (330 m) navigation channel and features a vertical clearance of 185 feet (56 m).

- 2,955 feet (901 m) of truss spans, consisting of ten spans each 292 feet (89 m) long, on average.

- The eastern 2,145-foot (654 m) cantilever structure, with arms measuring 538 feet (164 m) each flanking a central span of 1,070 feet (330 m). The eastern cantilever span is the secondary 1,070-foot-wide (330 m) navigation channel and features a reduced vertical clearance of 135 feet (41 m).

- 3,505 feet (1,068 m) of truss spans, consisting of twelve spans each 292 feet (89 m) long, on average.

- 1,715 feet (523 m) of 100-foot (30 m) girder spans

Excluding approaches, the bridge structures comprise a total length of 21,335 feet (6,503 m) on the upper deck and 22,125 feet (6,744 m) on the lower deck. Despite the varying height of the bridge, roadway grades are limited to 3% or less.[41][1] As completed, the bridge has two decks each capable of carrying three lanes of traffic. As of 2020, westbound traffic rides on the upper deck and is marked with two lanes of vehicle traffic, as well as a pedestrian/bicycle path separated from vehicles by a movable barrier. Eastbound traffic rides on the lower deck and features two lanes of vehicle traffic as well as a third lane that is activated during evening commute hours and serves as a shoulder when not in use. The extra lane features lights indicating that the lane is open or closed.[55] The third lane has been used for various purposes other than traffic, such as carrying a water pipeline during a drought.

The bridge stands on 79 reinforced concrete piers supported on steel H-piles. Nine piers stand on land, eight are in cofferdams near the Contra Costa terminus, and the remaining 62 are bell-type piers with a flared base.[1] The original deck was a 5.5-inch (140 mm) thick reinforced concrete slab, with a mortar wearing surface 0.5 inches (13 mm) thick.[56] To facilitate maintenance, the bridge was designed with two 2.5 inches (64 mm) lines (carrying compressed air and potable water) extending from end to end. Each deck was also equipped with three overhead maintenance tracks.[56]

Public transit service

Golden Gate Transit bus routes 40 and 580 provide public transportation across the bridge. Route 40 runs between the San Rafael Transit Center and the El Cerrito del Norte BART station.[57] Golden Gate Transit Route 42, which provided service to Richmond BART/Amtrak station, was folded into Route 40 in December 2015.[58]

Tolls

Tolls are only collected from westbound traffic headed to San Rafael at the toll plaza on the east side of the bridge. Since January 2019, the toll rate for (two axle) passenger cars and motorcycles is $6.[59] During peak traffic hours, high-occupancy vehicles (defined as two-axle vehicles without trailers, carrying three or more people; two-axle vehicles designed with two passenger seats without trailers, carrying two people; or motorcycles) pay a discounted toll of $3.[59][60][61] Since January 1, 2019, for vehicles with more than two axles, the toll rate is $16 for 3 axles and $5 per each additional axle over 3, up to a maximum toll of $36 for vehicles with seven or more axles.[59][62] Drivers may either pay by cash or use the FasTrak electronic toll collection device.

Historical toll rates

The following initial toll rates were adopted on July 10, 1956 prior to the opening of the bridge:

| Vehicle type | Axles/trailers | Toll |

|---|---|---|

| Class 1[lower-alpha 1] | vehicle alone | US$0.75 (equivalent to $7.05 in 2019)[lower-alpha 2] |

| Commutation book[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 4] | US$18.75 (equivalent to $176.32 in 2019) | |

| with 1-axle trailer | US$1.25 (equivalent to $11.75 in 2019) | |

| with 2-axle trailer | US$1.50 (equivalent to $14.11 in 2019) | |

| Truck[lower-alpha 5] | 2-axle | US$1.25 (equivalent to $11.75 in 2019) |

| 3-axle | US$1.75 (equivalent to $16.46 in 2019) | |

| 4-axle | US$2.50 (equivalent to $23.51 in 2019) | |

| 5-axle | US$3.00 (equivalent to $28.21 in 2019) | |

| 6-axle | US$3.50 (equivalent to $32.91 in 2019) | |

| 7-axle | US$4.00 (equivalent to $37.62 in 2019) | |

| Bus | 2-axle | US$1.50 (equivalent to $14.11 in 2019) |

| 3-axle | US$1.75 (equivalent to $16.46 in 2019) | |

| Other vehicles not specified above | US$5.00 (equivalent to $47.02 in 2019) | |

| Inaugural toll table notes | ||

| ||

The basic toll (for automobiles) on the seven state bridges, including the Richmond–San Rafael Bridge, was raised to $1 by Regional Measure 1, approved by Bay Area voters in 1988.[64] A $1 seismic retrofit surcharge was added in 1998 by the state legislature, originally for eight years, but since then extended to December 2037 (AB1171, October 2001).[65] On March 2, 2004, voters approved Regional Measure 2, raising the toll by another dollar to a total of $3. An additional dollar was added to the toll starting January 1, 2007, to cover cost overruns concerning the replacement of the eastern span.

The Metropolitan Transportation Commission, a regional transportation agency, in its capacity as the Bay Area Toll Authority, administers RM1 and RM2 funds, allocating a significant portion to public transit capital improvements and operating subsidies in the transportation corridors the bridges serve. Caltrans administers the "second dollar" seismic surcharge, and receives some of the MTC-administered funds to perform other maintenance work on the bridges. The Bay Area Toll Authority is made up of appointed officials put in place by various city and county governments, and is not subject to direct voter oversight.[66]

Due to further funding shortages for seismic retrofit projects, the Bay Area Toll Authority again raised tolls on all seven of the state-owned bridges in July 2010. The toll rate for autos on the Richmond–San Rafael Bridge was thus increased to $5.[67]

In June 2018, Bay Area voters approved Regional Measure 3 to further raise the tolls on all seven of the state-owned bridges to fund $4.5 billion worth of transportation improvements in the area.[68][69] Under the passed measure, the toll rate for autos on the Richmond–San Rafael Bridge will be increased to $6 on January 1, 2019; to $7 on January 1, 2022; and then to $8 on January 1, 2025.[70]

In September 2019, the MTC approved a $4 million plan to eliminate toll takers and convert all seven of the state-owned bridges to all-electronic tolling, citing that 80 percent of drivers are now using Fastrak and the change would improve traffic flow.[71] On March 20, 2020, at midnight, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all-electronic tolling was temporarily placed in effect for all seven state-owned toll bridges.[72]

Improvements

Seismic retrofit

In the fall of 2001, the bridge commenced an extensive seismic retrofit program,[73] similar to other bridges in the area.[74] The retrofit was designed by a three-way joint venture between Gerwick/Sverdrup/DMJM under a US$19,000,000 (equivalent to $31,900,000 in 2019) design contract awarded in 1995.[75] The retrofit is intended to allow the two-tier bridge to withstand a 7.4 magnitude earthquake on the Hayward Fault and an 8.3 magnitude quake on the San Andreas Fault. The foundation piers were strengthened by wrapping the lower section of structural steel in a concrete casing, installing new shear piles, and adding bracing to the structural steel towers.[76] Isolation joints and bearings were also added to the main bridge structures (cantilever spans over the navigation channels) to strengthen the structure.[77]

The fifty-year-old bridge was showing its age and also needed age-related maintenance, which was performed in conjunction with the seismic upgrade work. There were reports of cars being damaged while traveling on the lower deck by fist-sized concrete chunks falling from the joints of upper deck slabs.

A major part of the retrofit involved the long concrete causeway on the Marin side, which as part of the retrofit program, was nearly completely replaced. Because of the active use of the bridge, Caltrans designed the project to allow the bridge to remain open to traffic. For economy, schedule efficiency and traffic impact mitigation, much of the repair work was fabricated off site and shipped to the bridge by barge.

To reduce impacts to traffic the major work was performed at night. Caltrans kept two lanes of traffic moving in each direction during daylight hours, then reduced that flow to a single lane in each direction at night. Thus, one trestle was completely closed, and the other trestle had two-way traffic.

The concrete segments of the trestle were precast in Petaluma and barged to the site. At monthly intervals, tugs positioned barges with one or two 100-foot-long (30 m), 500-ton pre-cast concrete roadway segments, which a 900-ton barge-mounted crane lifted into place. Earlier, either two or four of the corroded, 50-foot (15 m) concrete segments of the old roadway were removed by crane. Then, a pile driver moved into position and drove new piles. After the new concrete road segment was in place, steel plates were used to temporarily fill the gaps, and the roadway was ready for morning traffic. At times, construction backed up traffic to Highway 101 into central San Rafael.

The completion of this retrofit, on September 22, 2005 was celebrated as a success despite the many challenges, including the deaths of two workers.

The retrofit was originally estimated by Caltrans engineers at US$329,000,000 (equivalent to $504,900,000 in 2019),[74] but Caltrans adjusted the estimate to US$393,272,000 (equivalent to $583,900,000 in 2019) in 2000 during the bidding process.[78] While most of the resulting bids were close to US$545,000,000 (equivalent to $809,100,000 in 2019), the low bid came in at US$484,403,479 (equivalent to $719,200,000 in 2019) from the Tutor-Saliba/Koch/Tidewater Joint Venture.[78] Caltrans revised their estimate to US$665,000,000 (equivalent to $960,200,000 in 2019) in May 2001 when more funds were appropriated for California's Toll Bridge Seismic Retrofit Program in Assembly Bill 1171.[79] The cost was again adjusted during an August 2004 review by Caltrans, this time to US$914,000,000 (equivalent to $1,237,200,000 in 2019).[80] The final cost of the retrofit, however, was $778 million, or $136 million below this August 2004 estimate.[80]

Third lanes

In both directions, the bridge is wide enough to accommodate three lanes of traffic. Currently the third lane on the lower deck is used as a right-hand shoulder or a "breakdown lane" and is marked along the bridge with the signs "Emergency Parking Only". The third lane on the upper deck is a separated bicycle and pedestrian path.[81]

In 1977, Marin County was suffering one of its worst droughts in history. A temporary on-surface pipeline, six miles (10 km) long, was placed in the third lane. The pipe transferred 8,000,000 gallons of water a day from the East Bay Municipal Utility District's mains in Richmond to Marin's 170,000 residents. By 1978, the drought subsided and the pipeline was removed. The disused third lane was then restriped as a shoulder.

In 1989, after the Loma Prieta earthquake, the third lane was opened up as a normal lane to accommodate increased traffic after the Bay Bridge was shut down because of a failure of that span. Many commuters from San Francisco drove across the Golden Gate Bridge into Marin and then across the Richmond–San Rafael Bridge to go to Oakland (and vice versa). After the Bay Bridge was reopened, the third lane was again closed.

On February 11, 2015, the Bay Area Toll Authority approved a plan to install a protected bike and pedestrian path on the wide shoulder of the upper deck of the bridge. The path was expected to be complete in 2017,[81] however it opened on November 16, 2019.[82] As part of the same project, a third eastbound lane[83] was added the previous year on the lower deck to be available for evening commutes.[55]

Closures

Like most San Francisco Bay bridges, this bridge is occasionally closed due to strong crosswinds. The bridge was closed on the morning of Friday, January 4, 2008 as a southerly wind gusting to nearly 70 mph (110 km/h) buffeted the span, knocking over four trucks on the lower deck and one truck on the upper deck. The bridge was closed for six hours. It was re-opened by late afternoon as the strong winds subsided.

This was not the first closure due to high winds. A tractor-trailer overturned in high winds in 1963, forcing the closure of two lanes.[84] At least one previous event occurred in the late 1970s when high northerly winds forced the CHP to close the bridge. Wind gusts (reported in the Marin Independent Journal) reached 80 mph.

On October 27, 2000 the toll plaza allowed people to cross free of charge due to a "shelter in place" order affecting toll booth operators. The order was given by the Richmond Fire Department in response to a release of toxic gas from a recycling plant.[85]

On February 7, 2019 the bridge was closed for several hours due to concrete falling from the upper deck to the lower.[86]

In popular culture & film

The novel Abuse of Power by Michael Savage has several important scenes set on the bridge. In one, the hero Jack Hatfield escapes his enemies by climbing the work ladders built into the piers.In the film Magnum Force, the bridge is in the background when Dirty Harry and the rookie cop are on motorcycles on the ship's decks where they attempt to subdue each other.[87] The bridge is also visible in the 1982 film 48 Hours.

References

- Raab, Norman A. (March–April 1954). "Pier Construction: Rapid Progress on Richmond-San Rafael Bridge Project" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. California Department of Public Works. 33 (3–4): 20–25, 32–33, 64. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- Prado, Mark (August 9, 2015). "Richmond-San Rafael Bridge Traffic volume hits five-year high". Marin Independent Journal. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- 2013 Named Freeways, Highways, Structures and Other Appurtenances in California, California Department of Transportation, 2013, pp. 150, 154 and 246. This State of California document indicates that the bridge has two official names, both enacted by legislative resolution, in 1955 and 1981 respectively.

- Snodgrass, Marion Myers; Dunning, Judith K (1992). "Changes in the Richmond Waterfront". Memories of the Richmond-San Rafael Ferry Company. Berkeley, Calif.: Bancroft Library. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- "Bridge Hearing Put Over Till Monday, 11th". Sausalito News. XXXXIII (15). April 9, 1927. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- "Propose to Construct Steel Bridge Over San Pablo Bay". Sausalito News. XXXXIII (9). February 26, 1927. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- "Local News". Sausalito News. XXXXIV (6). February 11, 1928. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- "Ferry Head to Apply for Span Permit". Sausalito News. XXXXIII (53). December 31, 1927. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- "One Bridge Gets Franchise, Other Given Rehearing". Sausalito News. XXXXIV (13). March 31, 1928. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- "Richmond Ferry is Sold to Bridge Co". Sausalito News. XXXXIV (8). February 25, 1928. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- "Rivals Agree On Contra Costa to Marin Crossing". Sausalito News. XXXXIV (38). September 28, 1928. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- "Bay Span Plan Gets Approval". Madera Tribune. United Press Dispatch. May 13, 1929. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- "Favorable Bridge Plans are Filed". Sausalito News. XXXXXV (47). November 22, 1929. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- "Bay Bridge Permit Given". Madera Tribune. United Press Dispatch. February 11, 1929. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- "Bridge Franchise Extension Asked". Sausalito News. LIII (42). October 20, 1938. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- "Richmond-S.R. Bridge Plan Under Way". Sausalito News. LIV (16). April 20, 1939. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- "Revive Richmond-S.R. Bridge Plan". Sausalito News. 62 (43). September 18, 1947. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- Thomas A. Tomasini, resident in San Francisco, is also noted as the inventor of the 1916 US 1200049 "Automobile Spring" as well as being a participant in the 1915 automobile Vanderbilt Cup Race, where he did not start due to crashing in practice.

- "Span Interests Eastern Capital". Sausalito News. XXXXIII (51). December 17, 1927. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- "Battle Expected Against Bay Span". Sausalito News. XXXXIV (2). January 14, 1928. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- "S.F. Turns Down Span Connection to Marin County". Sausalito News. XXXXIV (37). September 21, 1928. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- "Shipping Men Try to Block Tomasini Bay Bridge Plan". Sausalito News. XXXXIV (41). October 19, 1928. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- "Belvedere Bridge Could be Erected by Summer of '29". Sausalito News. XXXXIV (11). March 17, 1928. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- "Belvedere Span Hearing is Set". Sausalito News. XXXXIV (16). April 21, 1928. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- "Tomasini Signs Up Modjeski for Tiburon Bridge". Sausalito News. XXXXIV (15). April 14, 1928. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- "S.F. Delays Plan of Tomasini for North Bay Bridge". Sausalito News. XXXXIV (36). September 14, 1928. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- "Tomasini Gets Sausalito-Belvedere Bridge Permit". Sausalito News. XXXXIV (51). December 28, 1928. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- "Tomasini to Start Construction Work on Richardson Bay". Sausalito News. XXXXVI (26). June 27, 1930. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- "Tiburon-Belvedere Now Doesn't Want Tomasini Crossing". Sausalito News. XXXXVI (28). July 11, 1930. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- "Plan is Perfected for South Marin Highway Affair". Sausalito News. XXXXVII (46). November 13, 1931. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- Wood, Jim (May 2009). "History of a Highway: Marin's 101 was first established in 1909". Marin Magazine. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- Prado, Mark (March 23, 2011). "Moving Marin: The enormous role of bridges, ferries, trains, highways". Marin Independent Journal. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- "Plans Marin-S.F. Connection with Bridge and Tube". Sausalito News. XXXXIV (27). July 13, 1928. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- "Approve Bay Bridge Plan". Madera Daily Tribune and Madera Mercury. LX (63). July 16, 1932. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- "Tomasini's Bridge Plan Protested". Sausalito News. XXXXVIII (14). April 1, 1932. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- "Tomasini Bridge Permit Extension Again Asked". Sausalito News. LV (48). December 5, 1940. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- "20 Million Bond Issue Sought for Span-Tube". Sausalito News. LVI (34). August 21, 1941. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- "Rights to Span Tube Lost by Tomasini". Sausalito News. LVI (40). October 2, 1941. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- "Tomasini Says He Is Going to Build Span". Sausalito News. XLVIII (14). April 7, 1933. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- "Richardson Bay Bridge Plan Again Revived". Sausalito News. 63 (51). December 16, 1948. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- Raab, Norman A. (November–December 1953). "New Bay Crossing: Story of the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. California Department of Public Works. 32 (11–12): 1–6, 64. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- Raab, Norman C. (July–August 1956). "Record Span New Crossing: Richmond-San Rafael Bridge About Ready for Traffic" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. California Department of Public Works. 35 (7–8): 1–4, 22. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- "Bridging the Bay: Bridging the Campus - Richmond-San Rafael". UC Berkeley Library. December 22, 1999. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- "Frisco Adds Another Bridge To Skyline". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. August 16, 1956. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- "Straits Bridge Claim Challenged on Coast". The Milwaukee Journal. June 24, 1958. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- Seim, Chuck (2013). "Charles Seim: The Bay Bridge Oral History Project" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by Sam Redman. Berkeley: The Bancroft Library, University of California. p. 21. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

When it comes to the Richmond-San Rafael designed by Norman C. Raab, first of all, it zigzags because of the two alignments of the navigation channels. It goes up, and then it sags down, and then it goes up. The cardinal rule of aesthetics in a bridge is it has to soar. You can't sag it in the middle. The other is it connects from here to there as a straight line or as a curve line. You don't make an "S" out of it. Those violate both of those very strong principles. This engineer [Raab] was soundly criticized for creating this ugly bridge. Of course, his defense was, "I saved a million dollars by putting the sag in it." Which is probably true.

- Prado, Mark (September 1, 2006). "With little fanfare..." Marin Independent Journal. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- Interview with Chuck Seim (2013), p. 8 & 30. "Now, the twin spans, they were spanned by what we call a steel cantilever span. But the interesting thing is that these shipping channels were not parallel to one another. They angled."

- Interview with Chuck Seim (2013), p. 20. "Of course, everybody criticized the truss bridge on the Richmond-San Rafael, that Raab designed and they said, 'We don't want an ugly truss here.' [...] Well, if you had to award the ugliest bridge in the world, I think the Richmond-San Rafael would certainly be in the running. If not the first one, then top three. It is an ugly bridge. But that's a story that maybe we shouldn't get into. It was driven by economics, and it was driven by the obstinance of this one engineer that I referred to. He wouldn't change. He then proposed a truss for the Hayward area, and everybody said, 'No, we don't want that. It's an ugly bridge.' He said, 'Well, it's the most economical.'"

- Lin, TY (1999). "VIII Developing Prestressed Concrete Technology: The Richmond-San Rafael Bridge: Misjudgment to Save Money". ""The Father of Prestressed Concrete": Teaching Engineers, Bridging Rivers and Borders, 1931 to 1999" (Interview). Interviewed by Eleanor Swent. Berkeley: The Regents of the University of California. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

Lin: So, one architect asked [Wright], "What do you think of the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge?" "I think it should be sabotaged!" He meant that it should be bombed, it's so ugly looking.

- "Architect Chides Design Of New North Bay Bridge". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. May 1, 1953. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- Interview with Chuck Seim (2013), pp. 8–10. "Everybody working on that bridge - I think it's safe to say all the higher-echelon engineers - were the same engineers that worked on the San Francisco Bay Bridge. I had a chance to work with engineers who actually worked on the San Francisco Bay Bridge, and I used to read about that when I was a kid."

- Interview with Chuck Seim (2013), p. 30. "In 1956, the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge was opened. An interesting thing about that is that most of the senior engineers that worked on the Bay Bridge stayed over in San Francisco and worked on the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge, because they both used the same technology, with some minor variations."

- "Pier and Bent Layout: Richmond-San Rafael Bridge (Sheet No. RS-224)" (PDF). Caltrans. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- Prado, Mark (April 23, 2018). "Third lane on Richmond-San Rafael Bridge open for business". East Bay Times. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- Raab, Norman C. (July–August 1954). "Bridge Innovations: New Operation Facilities On Richmond-San Rafael Span" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. California Department of Public Works. 33 (7–8): 14–15, 32–33. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- "Route 40 Basic Bus Route Effective December 13, 2015". Golden Gate Transit. December 13, 2015. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- "GGT Routes 40 & 42 Merging - Service to Richmond BART Station Discontinued". Golden Gate Transit. November 10, 2015. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- "FasTrak". www.bayareafastrak.org. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- "Frequently Asked Toll Questions". Bay Area Toll Authority. June 1, 2010. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- "Toll Increase Information". Bay Area Toll Authority. June 1, 2010. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- "Toll Increase Information: Multi-Axle Vehicles". Bay Area Toll Authority. July 1, 2012. Archived from the original on December 30, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- "Tight Pants Cause High Toll Request". Spokane Daily Chronicle. AP. June 20, 1956. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- Regional Measure 1 Toll Bridge Program. bata.mtc.ca.gov; Bay Area Toll Authority. Archived November 1, 2010, at WebCite

- Dutra, John (October 14, 2001). "AB 1171 Assembly Bill – Chaptered". California State Assembly. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- "About MTC". Metropolitan Transportation Commission. October 15, 2009. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved October 15, 2009.

- "Frequently Asked Toll Questions". Bay Area Toll Authority. June 1, 2010. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- Cabanatuan, Michael (June 6, 2018). "Regional Measure 3: Work on transportation improvements could start next year". SFGate.com.

- Kafton, Christien (November 28, 2018). "Bay Area bridge tolls to increase one dollar in January, except Golden Gate". KTVU.

- "Tolls on Seven Bay Area Bridges Set to Rise Next Month" (Press release). Metropolitan Transportation Commission. December 11, 2018. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- Smith, Darrell (September 7, 2019). "Do you drive to the Bay Area? A big change is coming to toll booths at the bridges". The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- "Cash Toll Collection Suspended at Bay Area Bridges". Metropolitan Transportation Commission. March 20, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- "Welcome to the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge Seismic Retrofit Project". Caltrans. 2004. Archived from the original on April 4, 2004. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- Cabanatuan, Michael (May 3, 2004). "SAN RAFAEL / Seismic work jolts commute / Retrofit on Richmond Bridge on schedule, but drivers fuming". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- Vincent, John (September 1995). "Richmond-San Rafael Bridge Seismic Retrofit". Ben C. Gerwick, Inc. Archived from the original on April 29, 2004. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- "Project Description: Richmond-San Rafael Bridge". Ben C. Gerwick, Inc. 1998. Archived from the original on April 5, 2004. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- "Construction". Caltrans. 2004. Archived from the original on April 5, 2004. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- "Bid Summary, Contract No. 04-0438U4" (PDF). State of California Department of Transportation. August 9, 2000. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- California State Assembly. " Session of the Legislature". Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 907 p. 7396. "Assembly Bill 1171" (PDF). California Legislative Information. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- California Department of Transportation. "Toll Bridge Seismic Retrofit Program Report, Second Quarter 2005" (PDF). Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- Rivera, Renee. "Richmond-San Rafael Bridge Bike Path approved". bikeeastbay.org. East Bay Bicycle Coalition. Retrieved August 5, 2015.

- https://www.mercurynews.com/2019/11/17/long-awaited-richmond-san-rafael-bridge-transbay-bike-lane-opens/

- Prado, Mark (February 11, 2015). "Big changes planned for Richmond-San Rafael Bridge". Marin Independent Journal. Retrieved August 5, 2015.

- "Storm, Wind Lash Bay City". San Bernardino Sun. AP. January 31, 1963. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- Man dies in recycling plant explosion, October 27, 2000, access date July 3, 2012

- Falling concrete closes Richmond-San Rafael Bridge in both directions February 7, 2019

- Scene 34. Not Enough Experience. Magnum Force

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Richmond-San Rafael Bridge. |

- With Little Fanfare... Marin IJ article on the 50th anniversary of the bridge

- Richmond–San Rafael Bridge Retrofit Completed

- Caltrans Seismic Retrofit overview

- California Dept. of Transportation: Richmond–San Rafael Bridge History & Information

- Richmond–San Rafael Bridge at Structurae

- Univ. of California, Berkeley: Bridging the Bay: Richmond–San Rafael Bridge

- Decades of Struggle for Bicycle Access

- Bay Area Toll Authority—Bridge Facts—Richmond–San Rafael Bridge

- Footage of the official bridge opening ceremony from September 1956

- Eastern cantilever span from Point Richmond looking West

- Live Toll Prices for Richmond-San Rafael Bridge

- Raab, Norman A. (November–December 1953). "New Bay Crossing: Story of the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. California Department of Public Works: 1–6, 64. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- Raab, Norman A. (March–April 1954). "Pier Construction: Rapid Progress on Richmond-San Rafael Bridge Project" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. California Department of Public Works: 20–25, 32–33, 64. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- Raab, Norman C. (July–August 1954). "Bridge Innovations: New Operation Facilities On Richmond-San Rafael Span" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. California Department of Public Works: 14–15, 32–33. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- Raab, Norman C. (July–August 1956). "Record Span New Crossing: Richmond-San Rafael Bridge About Ready for Traffic" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. California Department of Public Works: 1–4, 22. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- "Freeway Approach to Bridge Opened in Marin County" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. California Department of Public Works: 29. November–December 1957. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- Raab, N.C. (1953). Richmond-San Rafael Bridge report (Report). Division of San Francisco Bay Toll Crossings. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- Raab, N.C. (1953). A preliminary report to Department of Public Works on a San Francisco-Tiburon crossing of San Francisco Bay (Report). Division of San Francisco Bay Toll Crossings. Retrieved July 12, 2016.