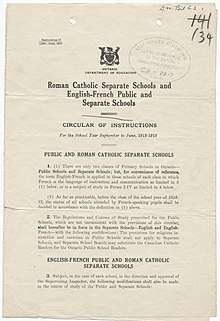

Regulation 17

Regulation 17 (French: Règlement 17) was a regulation of the Ontario Conservative government designed to shut down French-language schools at a time when Francophones from Quebec were moving into eastern Ontario.[1] It was a regulation written by the Ministry of Education, issued in July 1912 by the Conservative government of premier Sir James P. Whitney.[2] It forbade teaching French beyond grade two in all Separate schools[3].

In 1913, the Jesuits opened Collège Sacré-Coeur in Sudbury. It was bilingual up until 1914, at which time the Government of Ontario granted it a Charter and made no mention of language or religion. The College did not come under authority of the Department of Education for its programs or any subsidies. In 1916, the College became a free institution that was exclusively French.[4]

Regulation 17 was amended in 1913, and it is that version that was applied throughout Ontario.[5] As a result, French Canadians distanced themselves from the subsequent World War I effort, as its young men refused to enlist.[6]

French reaction

French Canadians reacted with outrage. Quebec journalist Henri Bourassa in November 1914 denounced the "Prussians of Ontario." With the World War raging, this was a stinging insult.[7] The policy was strongly opposed by Franco-Ontarians, particularly in the national capital of Ottawa where the École Guigues was at the centre of the Battle of the Hatpins. The newspaper Le Droit, which is still published today as the province's only francophone daily newspaper, was established by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate in 1913 to oppose the ban. Faced with separate school boards' resistance and defiance of the new regulation, the Ministry of Education issued Regulation 18 in August 1913 to coerce the school boards' employees into compliance.[8]

Ontario's Catholics were led by the Irish Bishop Fallon, who united with the Protestants in opposing French schools.[9] Regulation 17 was repealed in 1927.[10][11]

In 1915, the provincial government of Sir William Hearst replaced Ottawa's elected separate school board with a government-appointed commission. After years of litigation from ACFÉO, however, the directive was never fully implemented.[12]

The regulation was eventually repealed in 1927 by the government of Howard Ferguson following the recommendations of the Merchant-Scott-Côté report.[5] Ferguson was an opponent of bilingualism, but repealed the law because he needed to form a political alliance with Quebec premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau against the federal government. The Conservative government reluctantly recognized bilingual schools, but the directive worsened relations between Ontario and Quebec for many years and is still keenly remembered by the French-speaking minority of Ontario.

Despite the repeal of Regulation 17, however, French-language schools in Ontario were not officially recognized under the provincial Education Act until 1968.

The Ontario Heritage Trust erected a plaque for L’École Guigues and Regulation 17 in front of the former school building, 159 Murray Street, Ottawa. "L’École Guigues became the centre of minority-rights agitation in Ontario when in 1912 the provincial government issued a directive, commonly called Regulation 17, restricting French-language education. Mounting protests forced the government to moderate its policy and in 1927 bilingual schools were officially recognized." [13]

Desloges sisters and guards at Ottawa Guigues School in 1913

Desloges sisters and guards at Ottawa Guigues School in 1913 Protest in the streets of Ottawa, February 1916

Protest in the streets of Ottawa, February 1916

Further reading

- Barber, Marilyn. "The Ontario Bilingual Schools Issue: Sources of Conflict," Canadian Historical Review, (1966) 47$3 pp 227–248

- Cecillon, Jack D. Prayers, Petitions, and Protests: The Catholic Church and the Ontario Schools Crisis in the Windsor Border Region, 1910-1928 (MQUP, 2013)

- Croteau, Jean-Philippe. "History of Education in French-Speaking Ontario: A Historiographic Review." Canadian Issues (2014): 23-30 online

- Gaffield, Chad. Language, Schooling, and Cultural Conflict: The Origins of the French Language Controversy in Ontario (1987)

References

- Robert Craig Brown, and Ramsay Cook, Canada, 1896-1921: A nation transformed (1974) pp 253-62

- Barber, Marilyn. "Ontario Schools Question", in The Canadian Encyclopedia, retrieved November 20, 2008

- The History of a Diocese In Northern Ontario. Strasbourg France: Editions du Signe. 2014. p. 15. ISBN 978-2-7468-3158-2.

- The History of a Diocese in Northern Ontario. Strasbourg France: Éditions du Signe. 2014. p. 17. ISBN 978-2-7468-3158-2.

- SLMC. "Regulation 17: Circular of Instruction No. 17 for Ontario Separate Schools for the School Year 1912–1913", in Site for Language Management in Canada, retrieved November 20, 2008

- Gordon L. Heath (2014). Canadian Churches and the First World War. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 82–83. ISBN 9781630872908.

- Robert Craig Brown and David Clark MacKenzie (2005). Canada and the First World War: Essays in Honour of Robert Craig Brown. U. of Toronto Press. p. 107. ISBN 9780802084453.

- Leclerc, Jacques. "Circular of Instructions No. 18", in L'aménagement linguistique dans le monde, retrieved November 20, 2008

- Cecillon, Jack (December 1995). "Turbulent Times in the Diocese of London: Bishop Fallon and the French-Language Controversy, 1910–18". Ontario History. 87 (4): 369–395.

- Barber, Marilyn (September 1966). "The Ontario Bilingual Schools Issue: Sources of Conflict". Canadian Historical Review. 47 (3): 227–248. doi:10.3138/chr-047-03-02.

- Jack D. Cecillon, Prayers, Petitions, and Protests: The Catholic Church and the Ontario Schools Crisis in the Windsor Border Region, 1910-1928 (2013)

- The Project Gutenberg EBook of Bilingualism, by Hon. N. A. Belcourt K.C., P.C. Bilingualism Address delivered before the Quebec Canadian Club, at Quebec, Tuesday, March 28th, 1916

- Ontario Heritage Trust plaque