Alberta separatism

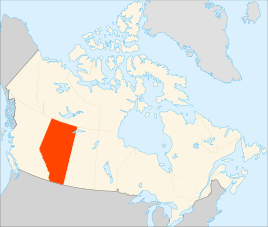

Alberta separatism (French: Séparatisme albertain) comprises a series of 20th and 21st century movements advocating the secession of the province of Alberta from Canada, either by forming an independent nation or by creating a new union with one or more of Canada's western provinces. The main issues driving separatist sentiment have focused on power disparity relative to Ottawa and other provinces, and Canadian fiscal policy, especially as it pertains to the energy industry.

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alberta |

|---|

|

| Topics |

| History |

| Politics |

| Timeline of Albertan history |

History

Foundations

Alberta was established as a province on September 1, 1905.[1] Alberta separatism comes from the belief that many Albertans hold that they are culturally and economically distinct from the rest of Canada, particularly Central Canada and Eastern Canada, because of economic imbalances whereby Alberta is a net over-contributor to the system of equalization payments in Canada.[2] Furthermore, the majority of Alberta's trade flows north-south with the United States and not east-west with the rest of Canada.

The Alberta economy was traditionally based on agriculture, but in the last half of the 20th century it changed to become based on industrial resource extraction, mainly oil and gas production. Alberta's political culture in the late 20th century was generally dominated by both small-"c" and large-"C" conservative politics and economics, whereas the rest of Canada tended to favour more left-of-centre policies and parties.

1930s separatism and the Alberta Social Credit Party

Separatism emerged in the 1930s within the Social Credit Party, which formed the Government of Alberta after the 1935 election. The federal government deemed implementing a form of social credit unconstitutional and invoked its rarely used power of disallowance under S.56 of the Constitution Act, 1867, thereby voiding provincial legislation. Premier William Aberhart did secure provincially-owned banks and distribution of prosperity certificates most of which were openly against the Government. Premier Aberhart's followers called for separation from Canada, but Aberhart himself counselled moderation and rejected secession. The separatist movement was ridiculed by the media as a fringe movement of the uneducated.[3]

1940s to 1960s: after World War II, monopolies, Alberta gas

Following World War II, the popular "Alberta First" opposition was formed to combat wastage and excessive export of gas. Albertans in general felt that they have been denied their fair return and usage of their own resources, and that outsiders had benefited disproportionately. In 1949, Alberta responded by passing legislation to strengthen control over export of gas from the Province. Ottawa responded by invoking the military in order to pressure Alberta to export its gas to the US. By 1954, it was widely understood that predatory encroachments from outside monopolies were backed by the federal government, in opposition of Albertan interests.[4]

1970s: beginnings of modern separatist ideals

The modern ideal for a separate Alberta nation began in the 1970s, as a response to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau's pursuit of bilingualism and Multiculturalism in Canada, and the National Energy Program. These programs were seen by many Albertans as an attack on oil resources; the promotion of Liberal "anti-Albertan" values were viewed as a negative influence by many Albertans.

In 1974, as Quebeckers were discussing separating from Canada, many Albertans also began to consider separation. This resulted in some Calgary-based citizens forming the Independent Alberta Association.[5] Central to the argument was the fact that Alberta would pay billions of dollars towards Canada, but without political representation equal to that of Central and Eastern Canada. Many expressed the opinion that Trudeau would continue his hard federalist stance producing unfavorable results for Western Canada including Alberta and its natural resources. Some, like Glenn Morrison, president of Renn Industries, did not agree with Alberta separatism but, believed strongly that Alberta needed increased representation in Ottawa and greater autonomy. In the end, the Independent Alberta Association did not move beyond association status, and did not form a political party.

Other influences in the 1970s included two major oil crises: coinciding with the Yom-Kippur War of 1973 and the Iranian Revolution of 1979. The first was caused by the decision of the US to support Israel, which in turn caused retaliation by Egypt and Syria, bringing on an oil embargo that resulted in Alberta receiving substantially less price for oil than the global market prices dictated.[6] Across North America, long lines could be seen at gas stations, and people started to realize the need to conserve energy resources.

The second oil crisis of 1979 was again due to decreased oil output, this time in the wake of the Iranian Revolution. In 1978, a revolutionary anti-American government headed by the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini overthrew the America-friendly government of the Shah of Iran.[7] Gasoline prices, which had earlier stabilized somewhat since 1973, spiked again. Some members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and a few similarly minded oil-rich nations had ceased all oil exports to the United States and countries that supported Israel. The price of oil sold to North America quadrupled within months, and service stations again ran out of fuel, long lines were evident at gas stations across North America.

The Alberta government and the Canadian federal government responded politically to address oil reserves and conservation of petroleum resources. In 1971, the Alberta Social Credit Party provincial government, headed by Harry Strom, created an environmental ministry, the first of its kind, with a mandate to manage and conserve Alberta's natural resources.[8] Federally, in 1974, the Office of Energy Conservation was created. Conflict arose between Alberta and Canada after the 1973 crisis, over the management and distribution of Alberta's oil resources, and financial wealth, setting the stage for Alberta separatism.

After Joe Clark's Progressive Conservatives won a minority government in 1979 defeating Pierre Trudeau's Liberal party Albertans were hopeful a change in federal energy policy would occur. These ideas were harnessed during Clark's unsuccessful 1980 election campaign. An Albertan Clark lost the election and resigned the leadership of the Progressive Conservative Party in 1983 after receiving only a 67% confidence vote at a party convention.

1980s and 1990s: Liberals, NDP, Conservatives, resurgence

In 1980, a Liberal majority government under Pierre Trudeau was formed. This caused the already brewing separatist movement in western Canada to attract thousands of people to rallies and coincided with the election of a separatist to the Alberta Legislature.[9]

In October 1980, the National Energy Program (NEP) was created by the federal government under Prime Minister Trudeau, and support for Alberta separatism and anger toward the Federal Government reached a new level of popular support. This program was widely thought to be an attempt by the federal government to seize full control over Alberta's natural resources. Notably, Trudeau introduced a tax to finance the federally owned energy company Petro-Canada and gave grants to Canadian-owned companies to encourage exploration.[10] After the introduction of the NEP, Alberta's oil industry slumped, with drastic reduction in the number of oil wells drilled. Abandonment of major projects such as Alsands caused high unemployment in Alberta. The Petroleum Incentives Program, part of the NEP, was criticized for luring exploration capital away from Alberta.[4]

Trudeau argued that the NEP would pave the way for Canada to become self-sufficient in energy but with the forced requirement of Alberta producers to sell domestically at a significant discount compared to world prices, which allowed the sponsored Petro-Canada the advantage in purchasing producing assets. Eastern Canadians would then be able to buy oil at below-market rates, and the federal government would have a view into an industry dominated by foreign owned petroleum companies. Trudeau argued that the NEP would help shield and promote self-sufficiency in Canada from the volatility of the international oil prices, but instead, economic disaster resulted. Alberta's unemployment rate rose from 4% to more than 10%, bankruptcies soared 150%, Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers later blamed the NEP for the loss of 15,000 jobs, a 22% drop in drilling activity, and a 25% decline in exploration budgets.[10] Industry cash flow and earnings fell from $4.7 billion in 1980 to $3.1 billion in 1981. Many prominent citizens were inspired to push forward Alberta separatist principles. This sentiment gave rise to the Western Canada Concept (WCC) and West-Fed which held popular, well-attended meetings across Alberta. Many of the people attracted to these parties were not necessarily advocating for independence, but were advocating for fair treatment of Alberta and her resources.

In 1980, Doug Christie, a British Columbia lawyer, formed the WCC in an effort to promote Western separatism. In 1982, Gordon Kesler was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Alberta in a by-election in Olds-Didsbury as a candidate of the WCC and attracted national attention.[11]

In addition, an organization called West-Fed was founded, led by Edmonton businessman Elmer Knutson, who was credited with inspiring the transformation of Western alienation ideas into a political movement." Knutson denied being a separatist, but West-Fed was widely regarded as a separatist organization. In 1983, Knutson attempted, but failed, to win the leadership of the Social Credit Party of Canada. A year later in 1984, Knutson founded the Confederation of Regions Party to advocate for a new Canadian constitution that would provide Alberta with more regional autonomy. The Confederation of Regions Party of Canada (CoR) was based on the premise that Canada consists of four regions, each of which should have equal representation in Parliament. By mid-1983 it was registered as an official provincial party in Alberta and by 1984 it was registered federally and ran 54 candidates but none were elected. Major platform initiatives included opposition to compulsory bilingualism and metrication, abolishing the Senate, and equal representation to the four regions.[4] A year later Knutson resigned, but in all had significantly inspired many Albertans to join Doug Christie's Western Canada Concept, which was running candidates in elections.

In a 1981 Alberta poll, 49% agreed that "Western Canadians get so few benefits from being part of Canada that they might as well go it on their own." Across the west, polls indicated about 1/3 agreement to this statement. In 1982, 84% of western respondents agreed they are dissatisfied with the federal government, 50% held it responsible for their poor economic situation, and 66% responded they did not trust the federal government.[4]

In response, Premier Peter Lougheed called a snap election in which the party nominated 78 candidates in the province's 79 ridings (electoral districts). Highlighted was major infighting and structural leadership problems within the WCC.

Although WCC won almost 12% of the popular vote (over 111,000 votes), Kesler was defeated after changing ridings, and no other candidate was elected. The WCC still managed a strong third place showing in another by-election, in Spirit River-Fairview, held in 1985, following the death of Grant Notley.[12]

The party's popularity declined after the Progressive Conservative Party, led by Brian Mulroney won a majority government, defeating Prime Minister John Turner in the 1984 federal election. Under Mulroney, the NEP was rapidly dismantled and as a Conservative, new hope reigned for Alberta in achieving a better negotiated resource wealth distribution. This caused the Alberta separatist movement to dissipate significantly. Yet, despite this sentiment, the Mulroney government was a disappointment since the majority of MPs were elected from central Canada, and Alberta's concerns largely ignored. By the time he left office in 1993, Mulroney was perhaps the most hated Prime Minister due to various allegations of corruption pertaining to the sale of Canadian assets.[13] Mulroney awarded the contract for maintenance of CF-18 fighter jets to the Montreal-based Bombardier Aerospace company, a decision that engendered so much anger in Western Canada, since Western Canada produced a better bid, that it directly led to the formation of the Reform Party of Alberta.

After this, the WCC experienced a resurgence, and in 1987 ran candidate Jack Ramsay, who in 1982 had become leader of the party. Ramsay notably and significantly argued for the Triple-E Senate as an alternative to Alberta separation, until 1986 when he reverted his opinion back to the previous separatist position of the WCC. In 1987 Ramsay joined the Reform Party of Alberta and ran in a by-election where he finished second. This would be the last time the party would run a candidate.

Alberta prominent citizen Preston Manning would take the Reform Party of Canada, a right-wing populist federal party, along the lines of non-separatist sentiments and significant popularity. Manning would attract many Albertans that were separatists. The Reform Party existed from 1987 to 2000 when it merged into the Canadian Alliance. Later, in 2003, it would merge with the Progressive Conservative Party to form the modern-day Conservative Party of Canada. These mergers left a significant void to those interested in furthering separatist principles.

2000s Reform to Conservative

Without the existence of the Reform Party to articulate Alberta's concerns, the separatist movement in the early twenty-first century began to organize meaningfully for the first time since the 1980s. Again though, separatism would place faith in a favourable federal government, only to again be disappointed.

In the 2004 federal election, the governing Liberal Party of Canada was returned with a minority government despite allegations of corruption. 61.7% of Alberta voters voted for the opposition Conservative Party - 22% supported the Liberals, although how many of these Conservative voters were separatist can only be guessed.

There was significant opposition within Alberta to the Kyoto Protocol as the Kyoto treaty was believed to have negative effects on the provincial economy, which is based to a large degree on the oil and gas industry. (Alberta had the world's second largest proven reserves of oil, behind only Saudi Arabia.[14])

In the 2004 general election, the Separation Party of Alberta nominated 12 candidates who won 4,680 votes, 0.5% of the provincial total. No candidates were elected. This was less support than the Alberta Independence Party attracted in the 2001 election, when 15 candidates attracted 7,500 votes.

Albertan Stephen Harper succeeded against the odds of the Canadian First-past-the-post voting system and in 2006 became Prime Minister of Canada in a minority government in the 2006 federal election. Harper had been a significant figure in the Reform Party, became leader of the Canadian Alliance in 2002, then merged with the PC Party in 2003, forming the Conservative Party of Canada. Due to Harper's Reform roots, Albertans held faith that he would be the trusted figure to protect Alberta's interests. As a result, Alberta's separatist movement sat on the side-lines, with uncertain prospects. Some pundits predicted that this result would cause support for separatism to ebb away.

The notion of Alberta secession from Canada gained sympathy from some figures within Alberta's conservative parties. Mark Norris, who was one of the contenders to succeed Ralph Klein as the Alberta premier, told the Calgary Sun in March 2006 that under his leadership, if a future federal government persisted in bringing in policies harmful to Alberta such as a carbon tax, "(Alberta is) going to take steps to secede."[15]

Also, some politicians believe, and at least one poll indicated that a much larger portion of the Alberta population may be at least sympathetic to the notion of secession than was indicated by election results. In January 2004, Premier Ralph Klein told the Canadian edition of Readers Digest that one in four Albertans were in support of separation. An August 2005 poll commissioned by the Western Standard pegged support for the idea that "Western Canadians should begin to explore the idea of forming their own country." at 42% in Alberta and 35.6% across the four Western provinces[16]

Late 2010s to early 2020s resurgence

Support for Albertan separatism has increased significantly with the Canadian federal election victory of Justin Trudeau's Liberal Party on October 19, 2015.[17][18][19][20][20][21] Federal Liberal leader Justin Trudeau, the son of Pierre Trudeau, became prime minister with a majority government, and re-inspired the Alberta separatist movement. While speaking at a town hall in Peterborough, Ontario, on January 13, 2017, Trudeau responded to a question about pipelines and his commitment to protecting Canada's environment. "We can't shut down the oilsands tomorrow. We need to phase them out. We need to manage the transition off of our dependence on fossil fuels. That is going to take time,"[22] The next day at a Calgary vs Edmonton Hockey game in Edmonton, Mr. Trudeau was loudly booed by the crowd.[23] His unpopularity in Alberta is a significant rallying point for Alberta separatists. The topic of Alberta separating from Canada is the subject of a growing number mainstream media reports.[24][20][21]

Peter Zeihan in his 2014 book The Accidental Superpower presented the reasons why he believed both Alberta and the U.S. would benefit from Alberta joining the United States as the 51st state.[25][18][19][20][21] Quote from page 263 of book:

The core issue is pretty simple. While the Québécois—and to a slightly lesser degree the rest of Canada—now need Alberta to maintain their standard of living, the Albertans now need not to be a part of Canada in order to maintain theirs.

Zeihan also stated that "Right now, every man, woman and child in Alberta pays $6,000 more into the national budget than they get back. Alberta is the only province that is a net contributor to that budget — by 2020, the number will exceed $20,000 per person, $40,000 per taxpayer. That will be the greatest wealth transfer in per capita terms in the Western world."[21] Per Statistics Canada, in 2015 Alberta paid $27 billion more into the federal treasury than it received back in services.[26]

A September 2018 poll by Ipsos indicated that 62% of Albertans believe that Alberta "does not get its fair share from Confederation" (up from 45% in 1997), 46% feel "more attached to their province than to their country" (up from 39% in 1997), 34% "feel less committed to Canada than I did a few years ago" (up from 22% in 1997), 18% believe "the views of western Canadians are adequately represented in Ottawa" (down from 22% in 2001), and 25% believe "My province would be better off if it separated from Canada" (up from 19% in 2001).[27][28]

A February 2019 poll from Angus Reid found 50% of Albertans would support secession from Canada but also found the likelihood that Alberta would separate to be "remote."[29]

After Justin Trudeau's re-election on October 21, 2019, in the Canadian federal election, #Wexit (a wordplay on "Brexit", the United Kingdom's departure from the European Union) trended on social media.[30] However, experts and an analysis from Hill+Knowlton Strategies, demonstrated that part of the push was due to disinformation and bots.[31][32] On November 4, 2019, the separation group "Wexit Alberta" applied for federal political party status.[33] On November 6, 2019, a poll conducted by Ipsos show a historic high of interest of secession from Canada in both Alberta and Saskatchewan provinces by 33% and 27%, respectively.[34][35] On January 12, 2020, Wexit Canada was granted eligibility for then next federal election.[36]

A May 2020 poll by Northwest Research for the Western Standard found that 41% of respondents would support independence in a referendum, 50% would be opposed, and 9% weren't sure[37]. Removing undecideds, 45% would support and 55% would be opposed. Respondents were also asked if they would support a referendum if "the federal government is unwilling to negotiate with Alberta on a new constitutional arrangement", 48% said yes, while 52% said no. Support for independence was higher outside of Alberta's two biggest cities, with Edmonton being the most opposed.

Legality of separation in Canada

In Canada the Clarity Act, which has been approved by the Supreme Court of Canada, governs the process a province should follow to achieve separation. The first step is a province wide referendum with a clear question. The size of majority support required by referendum is not defined.

Political parties interested in separation

Registered Alberta political parties

- Alberta Independence Party[38]

- Freedom Conservative Party of Alberta (previously named Separation Party of Alberta/Alberta First

- Wexit Alberta

Registered federal political parties

Opinion polling

| Date(s) conducted | Remain | Leave | Undecided | Lead | Sample | Conducted by | Polling type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14–19 May 2020 | 50% | 41% | 9% | 9% | 1,094 | Northwest Research | IVR | |

| 18–20 Dec 2019 | 55% | 40% | 6% | 15% | Research Co. | Online | Sample size was 1,000 for all of Canada | |

| 12-17 Nov 2019 | 75% | 25% | 50% | Abacus | Online | Sample size was 3,000 for all of Canada | ||

| 24 Oct–01 Nov 2019 | 54% | 33% | 13% | 21% | 250 | Ipsos | Online | |

| 11-17 Sep 2018 | 75% | 25% | 50% | 400 | Ipsos | Online | ||

See also

References

- "Alberta becomes a Province". Alberta Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- "Unpacking Canada's Equalization Payments for 2018-19 - The School of Public Policy". The School of Public Policy. January 17, 2018. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- Howard Palmer, Alberta: A New History (1990) p 272

- "The page has moved". lop.parl.ca. Archived from the original on January 29, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- "Desert Sun 26 March 1980 — California Digital Newspaper Collection". cdnc.ucr.edu. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- "The Energy Crises: 1973 and 1978-79 - Conventional Oil - Alberta's Energy Heritage". www.history.alberta.ca. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- "The Energy Crises: 1973 and 1978-79 - Conventional Oil - Alberta's Energy Heritage". www.history.alberta.ca. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- "The Energy Crises: 1973 and 1978-79 - Conventional Oil - Alberta's Energy Heritage". www.history.alberta.ca. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- Bell, Edward. "'Separatism and Quasi-Separatism in Alberta," Prairie Forum, Sep 2007, Vol. 32 Issue 2, pp 335-355

- "Remember when? Alberta's economy under Trudeau (Sr.)". BOE Report. October 6, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- Elections Alberta Archived July 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Elections Alberta Archived July 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Why hate Mulroney so?". Retrieved January 30, 2019 – via The Globe and Mail.

- http://www.redorbit.com/news/science/246436/alberta_oil__gas_prospect_restarts_operations/index.html

- "Calgary Sun". Calgary Sun.

- Kevin Steel, "A nation torn apart: An exclusive Western Standard poll shows more than a third of westerners are thinking of separating from Canada. What's dividing the country--and can anything be done to save it?," Western Standard August 22, 2005 online Archived May 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Loutan, Tyler (February 16, 2016). "Separatists getting louder with a quiet Alberta economy". 630 CHED. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- "Should Alberta Join the United States?". The Charles Adler Show. Soundcloud. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- Zeihan, Peter (December 26, 2014). "The End of Canada?". Retrieved December 26, 2017 – via YouTube.

- "The Last Best West: Meet Alberta's New Separatists". February 29, 2016.

- Gerson, Jen (March 18, 2015). "Why leaving Canada makes sense for Alberta, and U.S. would likely welcome a new state". National Post.

- "Trudeau's oil sands 'phase-out' comments spark anger in Alberta". Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- "Prime Minister Justin Trudeau Booed At Edmonton Oilers Hockey Game". HuffPost. January 16, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- "Talk of the Town: Is separatism rising here again?". Medicine Hat News. November 7, 2015. Archived from the original on April 18, 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- "Peter Zeihan says Alberta would be better off as 51st U.S. state". CBC News. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- Collins, Erin (June 10, 2017). "Analysis: Another decade, another Trudeau, another stab at sovereignty in Alberta". CBC News.

- "Western Alienation on the Rise? Not So Much". Ipsos. October 9, 2018.

- Solomon, Lawrence (December 7, 2018). "Lawrence Solomon: If Alberta turns separatist, the Rest of Canada is in big trouble". Financial Post.

- Desai, Desai (March 1, 2019). "A new poll suggests Alberta is the province that most wants to separate from Canada — not Quebec". National Post.

- Bogart, Nicole (October 22, 2019). "'Ottawa doesn't care': Western separatist movement gains traction as Albertans react to Liberal victory". Federal Election 2019. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- Laing, Zach (November 3, 2019). "Canada, Wexit targeted in Russian disinformation campaign, experts say". Calgary Herald. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- Romero, Diego (October 22, 2019). "#Wexit: Company says bots, aggregators boosted Alberta separatist movement on Twitter". CTV News. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- "Wexit group applies to become federal political party". cbc.ca. November 4, 2019.

- Maryam, Shah (November 6, 2019). "Separatist sentiment in Alberta, Saskatchewan at 'historic' highs: Ipsos poll". Global News. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- "Ipsos poll on Western separation records historic highs". Global News. November 6, 2019. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- Dryden, Joel. "Wexit party granted eligibility for next federal election". CBC. CBC/Radio Canada. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- Naylor, Dave. "POLL: 45-48% of Albertans back independence". www.westernstandardonline.com. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 29, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Further reading

- Bell, Edward. "Separatism and Quasi-Separatism in Alberta", Prairie Forum, Sep 2007, Vol. 32, Issue 2, pp. 335–355

- Pratt, Larry, and Garth Stevenson. Western separatism: the myths, realities & dangers (1981)

- Wagner, Michael. Alberta: Separatism Then and Now (St. Catharines, ON: Freedom Press Canada Inc., 2009) 138 pp, favourable account that concludes, "The odds of Alberta actually leaving Confederation are remote, at this point." However, he adds, "in my view, separatism has a future."

- Zeihan, Peter (2014). The Accidental Superpower: The Next Generation of American Preeminence and the Coming Global Disorder. (Chapter devoted to Alberta separatism)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Alberta |

- "On the Trail of Alberta Separatists", by Joe Obad, Alberta Views, March–April, 2004