Psalm 6

Psalm 6 is the 6th psalm from the Book of Psalms. The Psalm gives its author as King David. David's supposed intention in writing the psalm was that it would be for anyone suffering from sickness or distress or for the state of the Kingdom of Israel while suffering through oppression.[1]

_-_BL_Add_MS_37421.jpg)

The Geneva Bible (1599) gives the following summary:

- When David by his sins had provoked God’s wrath, and now felt not only his hand against him, but also conceived the horrors of death everlasting, he desireth forgiveness. 6 Bewailing that if God took him away in his indignation, he should lack occasion to praise him as he was wont to do while he was among men. 9 Then suddenly feeling God’s mercy, he sharply rebuketh his enemies which rejoiced in his affliction.

The psalm is the first of the seven Penitential Psalms, as identified by Cassiodorus in a commentary of the 6th century AD. Many translations have been made of these psalms, and musical settings have been made by many composers.

Early modern translations of Psalm 6

In 1532, Marguerite de Navarre, a woman of French nobility, included the sixth psalm of David in the new editions of the popular Miroir de l’âme pécheresse ("The Mirror of a Sinful Soul").[2] The psalm would also be later translated by the future Elizabeth I of England in 1544, when Elizabeth was eleven years old.[3] Many feel that the penitential Psalm had a reformation orientation to the readers of the day.

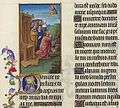

Psalm 6 in medieval illumination

The psalm was frequently chosen for illumination in medieval Books of Hours, to open the section containing the penitential psalms.

The Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (15th century)

The Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (15th century) A Book of Hours from Namur

A Book of Hours from Namur A 15th-century Book of Hours from the south of France. Surrounding the penitents are the dead in their graves.

A 15th-century Book of Hours from the south of France. Surrounding the penitents are the dead in their graves.

Themes

From Augustine's Enarrationes[4] till Eduard König and the advent of the form-critical method in the early 20th century this was considered one of the penitential psalms.[5]

Since then Hermann Gunkel has classed it as one of the Individual Lamentations,[6] as one of the"Sick Psalms".

For Martin Luther, the 6th Psalm was very important. It illustrated various central points of his theology.

Psalm 6 is in three parts, distinguished by the person.

- First, the psalmist addresses God and

- speaks for himself, and

- finally speaks to his enemies.

The psalmist expresses his distress in parts 1 and 2 and uses a rich palette of words to describe this distress, "powerless," "bone shaking," "extreme distress". He even expresses his distress by the excessiveness "of tears bathed layer", "eye consumed by grief," ...

In stating the enemies of the Psalmist, we understand that this distress is caused by relational problem. But it is unclear if he is innocent. However, he says he will be reinstated and that his opponents will be confounded. Trouble seems primarily psychological, but is also expressed through the body. It is as much the body as the soul of the psalmist cries out to God. In fact, it is also touched in his spiritual being, faced with the abandonment of God. In the absence of God emerges the final hope of the Psalmist, expressed confidence cry in the last three verses.

Heading

The Psalm header can be interpreted in different ways:[7]

- As an indication for the conductor

- for the musical performance (stringed instruments)

- eschatological in view of the end times (which lowers the potentially incorrect translation of the Septuagint close)

Uses

New Testament

Some verses of Psalm 6 are referenced in the New Testament:

- Verse 3a: in John 12:27.[8]

- Verse 8 in Matthew 7:23; Luke 13:27.[8]

In the Psalms almost all lament Psalms end with an upturn and here the upturn is a statement of confidence in being heard. Psalm 6:8-10.[8] . The sorrowful prayer models lamenting with an attitude of being heard, as seen in the book of Hebrews.Hebrews 5:7.[8]

Catholic

According to the Rule of St. Benedict (530 AD), Psalm 1 to Psalm 20 were mainly reserved for the office of Prime. According to the Rule of St. Benedict, (530) it was used on Monday, in the Prime after Psalm 1 and Psalm 25. In the Liturgy of the Hours as well, Psalm 6 is recited or sung to the Office of Readings for Monday of the first week.[9]

Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

- Verse 1 (which is almost identical to verse 1 of Psalm 38) is quoted in chapter 6 of 1 Meqabyan, a book considered canonical by this church.[10]

Music

In the Rule of St. Benedict the psalm is sung "At Prime on Monday with three other psalms, namely Psalm 1, Psalm 2 and Psalm 6."

Heinrich Schütz set Psalm 6 twice: once as "Ach, Herr, straf mich nicht", SWV 24, included in his Psalmen Davids, Op. 2 (1619),[11], and once as "Ach Herr mein Gott, straf mich doch nicht", SWV 102, as part of his Becker Psalter settings, Op. 5 (1628).[12] "Herr, straf mich nicht in deinem Zorn / Das bitt ich dich von Herzen" (not to be confused with "Herr, straf mich nicht in deinem Zorn / Lass mich dein Grimm verzehren nicht", a paraphrase of Psalm 38)[13][14] is a German paraphrase of Psalm 6, set by, among others, Johann Crüger (1640, Zahn No. 4606a).[15] Settings based on Crüger's hymn tune were included in the Neu Leipziger Gesangbuch, and composed by Johann Sebastian Bach (BWV 338).[16][17][18]

Psalm 6 also formed the basis of the hymn "Straf mich nicht in deinem Zorn" (Do not punish me in your anger) by Johann Georg Albinus (1686, excerpt; ECG 176). The French composer Henry Desmarest used the psalm in the work "Grands Motets Lorrain".

References

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- The Artscroll Tehillim page 8

- Poetry Foundation, Marguerite de Navarre

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2020-03-28. Retrieved 2020-03-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Beispielsweise von Gregor der Große, In septem Psalmos Paenitentialis; Alkuin, Expositio in Psalmos Poenitentialis; Cassiodor, Expositio in Psalmorum; Martin Luther, Dictata super Psalterium und Operationes in Psalmos.

- Antonius Kuckhoff, Psalm 6 und die Bitten im Psalter: ein paradigmatisches Bitt- und Klagegebet im Horizont des Gesamtpsalters. (Göttingen, 2011), p14

- Hermann Gunkel: Die Psalmen. 6. Auflage. (Göttingen 1986), p21.

- traduction par Prosper Guéranger, Règle de saint Benoît, (Abbaye Saint-Pierre de Solesmes, réimpression 2007) p46.

- Kirkpatrick, A. F. (1901). The Book of Psalms: with Introduction and Notes. The Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges. Book IV and V: Psalms XC-CL. Cambridge: At the University Press. p. 838. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- The main cycle of liturgical prayers takes place over four weeks.

- http://torahofyeshuah.blogspot.com/2015/07/book-of-meqabyan-i-iii.html

- Psalmen Davids sampt etlichen Moteten und Concerten, Op.2: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Becker Psalter, Op. 5, by Heinrich Schütz: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Cornelius Becker (1602). Der Psalter Dauids Gesangweis, "Der XXXVIII. Psalm"

- Scores of Herr straf mich nicht in Deinem Zorn, SWV 135, by Heinrich Schütz in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Zahn, Johannes (1890). Die Melodien der deutschen evangelischen Kirchenlieder (in German). III. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann. pp. 131–132.

- Gottfried Vopelius (1682). Neu Leipziger Gesangbuch, pp. 648–651.

- "Herr, straf mich nicht in deinem Zorn BWV 338". Bach Digital. Leipzig: Bach Archive. 2019-03-11.

- BWV 338 at Luke Dahn's www

.bach-chorales website..com

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Psalm 6. |