Pretenders to the Byzantine throne

The Byzantine Empire, the medieval continuation of the ancient Roman Empire, ceased to exist with the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, ending its line of emperors stretching from Augustus in 27 BC to the final emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos in 1453. After the Fall of Constantinople, both the Ottoman Empire (which occupied most of the Byzantine Empire's old territory including its capital) and Moscow (and its later incarnation, Russia; as the most powerful state practicing Eastern Orthodox Christianity), proclaimed themselves as Byzantium's successors as the "Third Rome".

Unlike many kingdoms and empires, the Byzantine Empire technically wasn't a hereditary monarchy; there were no formal succession laws in place to specify who was to succeed as emperor. As such, there can't be a legitimate pretender to the Byzantine throne as the possibility of a true "rightful emperor" died with the empire and its institutions in 1453. Despite this, there were claimants to the title in the immediate aftermath of Constantinople's fall, the most prominent being Constantine XI's brother Thomas Palaiologos and the son of Thomas, Andreas Palaiologos.

The last certain male-line descendants of the final few Byzantine emperors died out in the 16th century but that did little to stop forgers, pretenders, impostors and eccentrics from claiming descent from the ancient emperors, and in cases claiming the imperial title itself. Such claimants have frequently appeared in the centuries following the Fall of Constantinople and up until the present day. Though the majority of these pretenders have claimed descent from the final ruling Byzantine dynasty, the Palaiologoi, some have instead claimed descent from other dynasties, such as the Laskarids, Komnenoi, Kantakouzenoi or Angeloi. Later and modern would-be emperors are often accompanied by invented chivalric orders, typically with fabricated connections to the Byzantine Empire, despite the fact that chivalric orders were completely unknown in the Byzantine world.

Background

Succession in the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire was the medieval continuation of the ancient Roman Empire, with its capital having been transferred from Rome to Constantinople in the 4th century by Rome's first Christian emperor, Constantine the Great.[1] The term "Byzantine" was invented in the 16th century; the people in the empire continually self-identified as "Romans" and referred to their empire as the "Roman Empire" or "Romania" (meaning "land of the Romans") throughout its existence.[2] As the successor of the ancient Roman emperors, the power of the Byzantine emperor (offially titled the "Emperor of the Romans"; in later times the "Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans") was nearly absolute; being the supreme judge, the sole legitimate legislator, the highest military commander and the protector of the Christian church. There was a senate in Constantinople, ostensibly the continuation of the ancient Roman Senate, but it had little real influence, only potentially playing an important role in the aftermath of the deaths of emperors, when it theoretically held the power to appoint the next ruler. The senate's role in the process wasn't as decisive as it had been in some portions of ancient Roman history; the dead emperor had often designated a successor in his lifetime, often even crowning his designated heir as co-emperor, and thus ratification by the senate was only a formality. If there was no clear designated successor, the succession often came down to either senatorial or (more frequently) military support.[3]

Though the succession to the throne might often have been de facto hereditary, with emperors crowning their sons as co-emperors for generations, ensuring the creation of dynasties,[3] formal hereditary succession (especially in the way succession worked in Western Europe) was never adopted in the Byzantine Empire. This was clearly illustrated during the events of the Fourth Crusade in 1202–1204, when crusaders arrived at Constantinople with the aim of placing Alexios IV Angelos on the throne of the Byzantine Empire. Alexios IV's father Isaac II had been deposed by his brother (and Alexios IV's uncle), Alexios III, in 1195. Although Alexios IV would have been the rightful heir of Isaac II from the perspective of the Crusaders from Western Europe, the citizens of the empire itself were unconcerned with his cause as Alexios III, according to their own customs, was not an illegitimate ruler in the way he would have been in the West.[4] Of the 94 emperors who reigned from Constantinople's proclamation as Roman capital in 330 to the city's fall in 1453, 20 had started their careers as usurpers. Because obtaining the throne through usurpation wasn't seen as illegitimate, revolts and civil wars were frequent in the empire; more than thirty of its emperors had to face large-scale revolts against their rule.[5] Many of the empire's most prominent dynasties, including the Macedonian, Komnenos, Angelos and Palaiologos dynasties, were all founded through usurpers seizing power by displacing a previous ruling dynasty.[6][7][8][9]

Fall of the Byzantine Empire

In 1204, Constantinople was captured and sacked by the Crusaders of the Fourth Crusade. The city remained under control of their new empire, the Latin Empire, until it was recaptured by Michael VIII Palaiologos in 1261.[10] The efforts of Michael VIII's son and great-grandson, Emperors Andronikos II and Andronikos III, in the late 13th and early 14th centuries represented the last genuine attempts at expanding and restoring lost imperial territory.[11] A six-year-long civil war after Andronikos III's death was catastrophic for the already weakened empire, allowing the Serbian ruler Stefan Dušan (r. 1331–1346) to overrun most of the remaining Byzantine territory and establish a Serbian Empire. In 1354, an earthquake at Gallipoli devastated the fort, allowing the Ottomans, at the time of the war's beginning rulers of a small territory in western Anatolia, to establish themselves in Europe.[12] By the time the Byzantine civil wars had ended, the Ottomans had defeated the Serbians and subjugated them as vassals. Following the Battle of Kosovo, much of the Balkans became dominated by the Ottomans.[13]

On 2 April 1453, the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II laid siege to the depopulated Constantinople with an army of 80,000 men and a large numbers of irregulars. The Byzantines attempted to defend their city, but their forces numbered only c. 7,000 (2,000 of whom were foreign forces having travelled to the city to aid them).[14] After a two-month siege, the city finally fell on 29 May 1453. The final emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, was last seen casting off his imperial regalia and throwing himself into hand-to-hand combat after the walls of the city were taken.[15]

In the aftermath of the city's fall, Mehmed II assumed the title Kayser-i Rûm (Caesar of the Roman Empire), portraying himself as the successor of the Byzantine emperors. Contemporaries within the Ottoman Empire recognized Mehmed's assumption of the imperial title. The historian Michael Critobulus described the sultan as "Emperor of Emperors", "autocrat" and "Lord of the Earth and the sea according to God's will". In a letter to the Doge of Venice, Mehmed was described by his courtiers as the "Emperor". Other titles were sometimes used as well, such as "Grand Duke" and "Prince of the Turkish Romans".[16] The citizens of Constantinople and the former Byzantine Empire (which would still identify as "Romans" and not "Greeks" until modern times) saw the Ottoman Empire as still representing their empire; the imperial capital was still Constantinople (and would be until the end of the Ottoman Empire in the 20th century) and its ruler, Mehmed II, was the emperor.[17]

In addition to being the direct geopolitical successors of the Byzantine Empire, the Ottomans also claimed Byzantine ancestry from at least the 16th century onwards,[18] claiming that Ertuğrul, the father of the Ottoman dynasty's founder Osman I, was the son of Suleyman Shah, who was in turn supposedly the son of John Tzelepes Komnenos, a renegade prince of the Komnenos dynasty and a grandson of Emperor Alexios I.[19] Due to the chronological distance between some of the supposed ancestors, this particular line of descent is unlikely and the supposed Komnenid ancestry was probably created as a legitimizing device in regards to the many Orthodox Christians the Muslim Ottomans ruled.[19][20]

History

Direct imperial heirs

In the aftermath of the Fall of Constantinople, the existence of several potential claimants to the imperial throne of Constantinople represented a real threat to the rule of Sultan Mehmed II. Though Constantine XI did not have any children, the last emperor had surviving relatives and there were also living descendants of other past imperial families, such as the Komnenoi, Laskarids and the Kantakouzenoi. Although the Ottomans began a campaign of either carefully watching the activities of such claimants or outright eliminating them (for instance, many of the Kantakouzenoi were mass executed in Constantinople in 1477), some escaped their grasp. A passenger list for a Genoese ship which escaped the city's fall in 1453 with Byzantine refugees onboard lists among the people present on the ship no less than six Palaiologoi, two Laskarids, two Komnenoi, two Kantakouzenoi and two members of the Notaras family (relatives of Loukas Notaras, the last megas doux in the empire).[21]

The most direct claimants to the Byzantine Empire were Constantine XI's surviving brothers, Demetrios and Thomas, who ruled as co-despots of the Morea. Though the two might have aspired to use their territory in southern Greece as a rallying point to re-establish the empire, their constant bickering with each other meant that they did not represent a threat to Ottoman rule.[21] Furthermore, the two brothers had to battle with the Kantakouzenoi family for control, facing an uprising led by Manuel Kantakouzenos, the great-great-grandson of Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos. Manuel was defeated with Ottoman help, but in turn the Ottmans demanded a tribute which neither brother was able to pay. The subsequent Ottoman invasion of the Morea in 1458 significantly reduced the territory and authority of the Palaiologoi.[22] Nevertheless, they continued to squabble with each other and by 1460, Mehmed II's patience had worn out and combined with the threat posed by Thomas's repeated appeals to the Pope to launch a crusade against the Ottomans, Mehmed invaded and seized the Morea, ending the despotate.[23]

Demetrios was captured by the Ottomans and was forced to turn over his wife Theodora and his daughter Helena to the sultan's harem. He then lived for years at Adrianople until he for unknown reasons lost the favor of the sultan in 1467 after which he became a monk, dying in 1470. Helena had died before him and Theodora survived him for only a few weeks, ending his line. Thomas was not taken prisoner and instead escaped into exile with Venetian aid, settling in Rome after being rewarded with pensions and honours by the Pope. He spent much of the time until his death in 1465 travelling around Italy hoping to rally support for his cause.[24] Thomas had four children which carried on the Palaiologos name after his death. His oldest daughter, Helena, married Lazar Branković, the Despot of Serbia, and had three daughters (though none of them carried the name Palaiologos). She died as a nun in 1473 after the Ottomans had conquered Serbia. Thomas's younger daughter Zoe married Ivan III, the Grand Prince of Moscow, a marriage which resulted in four sons and allowed the Russians to later forward the claim that Moscow was the "Third Rome".[25]

Thomas's two sons were named Andreas and Manuel, and were raised in Italy. Manuel eventually returned to Constantinople, much to the surprise of people in Western Europe, and lived out his life under Ottoman rule. He had two sons; Andreas, who became a Muslim, and John, who died young.[25] Manuel's older brother Andreas aspired to restore the Byzantine Empire and though the Pope only accepted him as the rightful Despot of the Morea, he took for himself the title imperator Constantinopolitanus. Little came of Andreas's dreams, he died poor in Rome in 1502 having twice sold his imperial claims (including his rights to the thrones of Constantinople, Trebizond and Serbia); first to Charles VIII of France in 1494 and later as part of his will to Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon.[26]

It is possible that Andreas had children, Russian documents from the time suggest that he had a daughter called Maria who married Prince Vasily Mikhailovich of Vereya-Belozersk and it is possible that a Constantine Paleologus employed in 1508 as part of the Papal guard was his son. In either case, the descendants of the immediate relatives of the final Byzantine emperors were extinct by the 16th century.[26] After the death of Andreas in 1502, his claim to the Despotate of the Morea was immediately taken up by the unrelated Albanian noble Constantine Komnenos Arianites (who claimed descent from the Komnenos dynasty), who also claimed other titles such as "Prince of Macedonia" and "Duke of Achaea", but never the imperial title. After Constantine's death in 1530, the title of Despot of the Morea fell into disuse.[27]

Another branch of the Palaiologoi, descendants of Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos (r. 1282–1328), ruled as Marquises of Montferrat until 1533. Despite their documented end, the name "Montferrato-Paleologo" is recorded on the island of Cephalonia until the 17th century, though these Palaiologoi seem to have claimed no connection to the imperial family.[28]

Later pretenders

The extinction of the senior branch of the imperial Palaiologoi did not stop claimants to the Byzantine throne from appearing in various parts of the world.[26] There were many Byzantine refugees who legitimately bore the name Palaiologos but were unrelated to the emperors since the family had been extensive for centuries. Many of them fabricated links to the emperors as this made them more respectable. Many such Palaiologoi settled in northern Italy, in cities such as Pesaro, Viterbo or Venice.[29] Palaiologoi and other Byzantine refugees were often welcomed in Western Europe, partly due to Western European powers being conscious of their failure to prevent Byzantium's fall. Though the Palaiologoi, imperial or not, were mainly concentrated in northern Italy, other Greek nobles travelled across Europe, many ending up in Rome, Naples, Milan, Paris and in various cities in Spain.[30]

In the late 16th century, a theologian by the name Jacob Palaeologus, originally from Chios, became a Dominican friar in Rome. Jacob travelled across Europe, boasting of his descent and claiming to be a grandson of Andreas Palaiologos. Jacob's increasingly heterodox views on Christianity eventually brought him into conflict with the Roman church; he was burnt as a heretic in 1585. Jacob had children, though little is known of most of them. One of his sons, Theodore, lived in Prague in 1603 and referred to himself as a genuine member of the old imperal family and a "Prince of Lacedaemonia", though the authorities in Prague convicted him as a forger.[29]

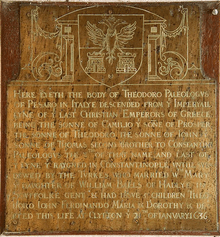

There was an Italian assassin and soldier called Theodore Paleologus who claimed descent from Thomas Palaiologos and died in 1636, being buried at Landulph in Cornwall. Though most of Theodore's supposed lineage of descent (as presented on his tombstone) is plausible, he claimed to be a descendant of a John Paleologus, son of Thomas, otherwise unattested in historical records. Although explanations for John's omission in earlier records of the children of Thomas have been put forward, such as John possibly being illegitimate or Theodore being mistaken in regards to his name, Theodore's supposed ancestry can't be proven with certainty.[31] Several of Theodore's closer relatives are known, such as his uncles Scipione and Leonidas Paleologus, both convicted for murder in Pesaro (Theodore's ancestral home city) and several of Theodore's children and descendants. When his daughter Dorothy married the Cornishman William Arundel in 1656, she was referred to as "Dorothea Paleologus de stirpe imperatorum", noting that she was of "imperial stock".[32] The only one of Theodore's children known to have had children of his own was Ferdinand Paleologus, born in 1619, who emigrated to Barbados. Ferdinand died in 1670 and had a son, Theodorious, who died in Corunna, Spain in 1693.[33] The line continued in the daughter of Theodorious, called Godscall Paleologue and born in 1694, after her father's death. She is last attested as a little orphan girl in Wapping or Stepney in London in 1695, after which she disappears from history.[34]

Another line of pretenders to the Byzantine Empire were the Kings of France. Though the Spanish monarchs, Isabella I and Ferdinand II, and their successors did not use the titles willed to them by Andreas Palaiologos, King Charles VIII of France had legitimately entertained the idea of conquering Constantinople from the Ottoman sultan Bayezid II. His successors as King of France; Louis XII (r. 1498–1515), Francis I (r. 1515–1547), Henry II (r. 1547–1559) and Francis II (r. 1559–1560), continued to claim and use imperial titles and honors.[35] Like Charles VIII, Francis I similarly made plans to spearhead a crusade against the Ottomans, though those plans never materialized.[36] Not until Charles IX in 1566 did the imperial claim come to an eventual end through the rules of extinctive prescription as a direct result of desuetude, or lack of use. Charles IX wrote that the imperial Byzantine title "is not more eminent than that of king, which sounds better and sweeter".[35]

The Angeloi and the Constantinian Order

Though the imperial Palaiologoi went extinct in the 16th century, the Palaiologoi were not the only dynasty to have governed the Byzantine Empire. By 1545, a family with the last name Angelos, who alleged descent from the Angelos dynasty (which had ruled the Byzantine Empire 1185–1204), had publicly emerged as claimants to the Byzantine Empire and as the heads of a self-proclaimed chivalric order; the Imperial Constantinian Order of Saint George (an order they claimed to have been founded by Constantine the Great in the 4th century).[30] The claims that this order represented an ancient imperial institution and something which many emperors had served as Grand Masters for is fantasy; there are no Byzantine accounts of such an institution ever existing.[37] Furthermore, chivalric orders, especially in a western sense, were completely unknown in the Byzantine world.[38]

The claim of these Angeloi to descend from Byzantine nobility was accepted in Western Europe without much dispute; there were already several known descendants of Byzantine nobility across the continent, legitimate or not.[30] Because they had prominent familial connections and through some means managed to convince the Popes of the legitimacy of their descent and their order, they reached a position more or less unique among the various Byzantine claimants.[37] Any imperial ancestry can't be proven for these later Angeloi, though it is possible that they descended either directly or collaterally from less well known children or cousins of the Angeloi emperors.[39] Their earliest certain ancestor was the Albanian Andres Engjëlli (hellenized as "Andreas Angelos"), alive in the 1480s, who later generations claimed held the titles "Prince of Macedonia" and "Duke of Drivasto".[40]

In 1545, the brothers Andrea (not the same Andrea as the aforementioned one) and Paolo Angelo were officially acknowledged as descendants of the Angeloi emperors by Pope Paul III. The two brothers were also guaranteed the right to inherit territory in the former Byzantine Empire, should such territory be recovered from the Ottomans.[41] The Angeloi, or Angeli Comneni, remained Grand Masters of their Constantinian Order until 1698 when Giovanni Andrea Angelo Flavio Comneno Lascaris Paleologo, who also claimed the titles of "Prince of Macedonia", "Duke of Thessaly" and "Count of Drivasto, Durazzo etc." upon his death assigned the order not to any living relatives but to Francesco Farnese, the Duke of Parma.[42] Farnese's right to the order was confirmed by Pope Innocent XII and Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I. The order exists to this day, now under the rule of the Bourbon family, confirmed as a religious-military order in a 1718 papal bull owing to a notable success in liberating Christians in the Peloponnese. Alongside the Sovereign Military Order of Malta it is the sole international Catholic Order which still has this status today.[43] Genuine historical figures of their family (verifiable outside of their own genealogies), claimed to have been Grand Masters (and listed with the titles attributed to them by later generations) include:

- Andrea (I) Angelo Flavio Comneno, "Duke and Count of Drivasto and Durazzo", supposed Grand Master c. 1453–1457/1470.[44]

- Paolo Angelo Flavio Comneno, "Duke and Count of Drivasto and Durazzo, Archbishop of Durazzo", supposed Grand Master c. 1447–1468/1469.[44]

- Pietro (I) Angelo Flavio Comneno, "Duke and Count of Drivasto and Durazzo", supposed Grand Master c. 1469–1511/1512.[44]

- Giovanni Demetrio Angelo Flavio Comneno, "Prince of Cilicia", supposed Grand Master c. 1511–1570.[44]

The historically verified Grand Masters of the Angeli Comneni family, who actively claimed Byzantine origin, were:

- Andrea (II) Angelo Flavio Comneno, "Prince of Macedonia, Duke and Count of Drivasto and Durazzo", Grand Master c. 1545–1580.[44]

- Girolamo (I) Angelo Flavio Comneno, "Prince of Thessaly", joint-Grand Master c. 1570–1591.[44]

- Pietro (II) Angelo Flavio Comneno, "Prince of Macedonia, Duke and Count of Drivasto and Durazzo", Grand Master 1580–1592.[44]

- Giovanni Andrea (I) Angelo Flavio Comneno, "Prince of Macedonia, Duke and Count of Drivasto and Durazzo", Grand Master 1592–1623 and 1627–1634.[44]

- Angelo Maria Angelo Flavio Comneno, "Prince of Macedonia, Duke and Count of Drivasto and Durazzo", Grand Master 1634–1678.[45]

- Marco Angelo Flavio Comneno, "Prince of Macedonia, Duke and Count of Drivasto and Durazzo", Grand Master 1678–1679.[45]

- Girolamo (II) Angelo Flavio Comneno, "Prince of Macedonia, Duke and Count of Drivasto and Durazzo", Grand Master 1679–1687.[45]

- Giovanni Andrea (II) Angelo Flavio Comneno, "Prince of Macedonia, Duke and Count of Drivasto and Durazzo", Grand Master 1687–1698.[45]

Though their order still exists, the Angeli Comneni died out with Giovanni Andrea in 1698, although some people claiming relation to him are attested thereafter. There was one Johannes Antonius Angelus Flavius Comnenus Lascaris Palaeologus, who died in Vienna in 1738, that claimed descent not only from the Angeloi but also from Theodore II Palaiologos, a despot of the Morea and son of Emperor Manuel II. Johannes referred to himself as "Princeps de genere Imperatorum Orientis" and claimed connection with the Constantinian Order.[42] Among later "Byzantine pretenders", Johannes was not alone in making claims to the Constantinian order, or other invented chivalric orders. Many later forgers of Byzantine claims purported that they were either part of the Constantinian Order, or its legitimate Grand Master.[46]

19th and early 20th century pretenders

In 1830, an Irish man by the name Nicholas Macdonald Sarsfield Cod'd, living in Wexford, petitioned George Hamilton-Gordon, the Earl of Aberdeen, and Henry John Temple, the Viscount of Palmerston, to press his "ancestral" claim on the newly created Kingdom of Greece, after the throne had been offered to and declined by Leopold I of Belgium.[38] An obscure Irishman claiming the throne of Greece is noteworthy as actual European royalty were offered the title at the time, with many refusing to accept it due to the personal danger presented by becoming king of a new and war-torn country.[47] Nicholas claimed descent not only from the final Palaiologoi but also from Diarmait Mac Murchada, a medieval King of Ireland. He created large and elaborate genealogies and referred to himself as the "Comte de Sarsfield of the Order of Fidelity Heir and Representative to his Royal Ancestors Constantines, last Reigning Emperors of Greece subdued in Constantinople by the Turks". After his claims were ignored by Hamilton-Gordon and Temple, Nicholas sent a letter to William IV, the King of the United Kingdom, and might have sent letters to Charles X, the King of France, Nicholas I, the Emperor of Russia, Frederick William III, the King of Prussia, and Gregory XVI, the Pope. None of them ever acknowledged his claims.[38]

A wealthy 19th century Greek merchant by the name Demetrios Rhodocanakis, originally from Chios but living in London, styled himself as "His Imperial Highness the Prince Rhodocanakis" and actively sought support for his claim to not only be the Grand Master of the Constantinian Order of Saint George but also to be the rightful Byzantine emperor. Rhodocanakis published several fabricated, but extensive, genealogies to assert his descent and though his claims were eventually debunked by the French scholar Emile Legrand, Rhodocanakis had at that point already received recognition from several important parties, such as the Vatican and the British Foreign Office.[46]

There are Palaiologoi who live in present-day France and Malta who sometimes allege to be the descendants of Theodore II Palaiologos, the despot of the Morea. According to their genealogies, Theodore had an otherwise unattested son by the name Emanuel Petrus (Manuel Petros) from which they descend. One of these Palaiologoi was the 19th/20th century French diplomat Maurice Paléologue, who in his lifetime repeatedly asserted his imperial descent.[28] Maurice's ancestors were not directly from Greece, but from Romania. The actual origin of the Romanian Palaiologoi can be traced to members of the Orthodox community in Constantinople being entrusted to governing positions in the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia by the Ottomans in the 18th century. The aristocrats sent to Moldavia and Wallachia included people with the last name Palaiologos, though any imperial descent is dubious and can not be proven with certainty. Also sent to Romania were aristocrats with the last name Kantakouzenos, purporting to be descendants of Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos.[42] Though their genealogy is somewhat unclear in the mid-15th to 16th centuries,[48] these Kantakouzenoi, who survive to this day as the Cantacuzino family, are according to the 20th-century byzantinist Steven Runciman "perhaps the only family whose claim to be in the direct line from Byzantine Emperors is authentic".[49]

Though there had been a Greek delegation sent to Italy and England after the Greek War of Independence, in search for supposed heirs of the Byzantine emperors, they found no living heirs of their ancient emperors. The failure of this delegation to find living Palaiologoi did not stop further claimants from emerging in England. Upon the deposition of the first King of Greece, Otto, in 1862, a man by the name Theodore Paleologo, probably from Malta but living in England, attempted to press his claim to the Greek throne. Theodore died in 1912, aged 89, and going by the headstone of his widow Laura's grave, his full name was "Theodore Attardo di Christoforo de Bouillon, Prince Nicephorus Comnenus Palaeologus". Theodore was probably related to a woman buried at the same gravesite as his widow, "Princess Eugenie Nicephorus Comnenus Paleologus", born in 1849 and dead in 1934 and described by her tombstone as "a descendant of the Grecian Emperors of Byzantium". Eugenie married a colonel, Edmund Hill Wickham, and had four sons. The oldest son, "Constantine Dougals Prince Paleologus", died in 1900 at the age of 20. His younger brothers, though they appear to have used the last name "Cristoforo de Bouillon Wickham" rather than Paleologus, are all referred to as "Princes of the house of Paleologus" on their memorial stone.[50]

Notable modern pretenders

Eugenio Lascorz

Eugenio Lascorz y Labastida (26 March 1886 – 1 June 1962) was a Spanish lawyer and the son of a man called Manuel Lascorz y Serveto (1849–1906), in turn the son of a laborer by the name Victoriano Lascorz y Abad (d. 1886), the son of a man called Alonso Lascorz y Cerdan. Wishing for a more prestigious origin, Eugenio believed that his last name Lascorz was a Spanish corruption of Laskaris, the last name of the dynasty which had ruled as Byzantine emperors in Nicaea from 1204 to 1261. Eugenio obtained "certification" of his ancestry in 1917 and "rectified" his father's birth records, replacing the last name Lascorz with "Lascaris". Similar "corrections" would be done to the birth records of other relatives over the course of the ensuing decades. His marriage with a woman called Nicasia Justa Micolau y Traver Blasco y Margell resulted in several children; all given names reminiscent of the emperors of old, such as Teodoro, Constantino, Alejandro and Juan Arcadio.[51]

Eugenio issued a manifesto to "the Greek people" in 1923, referring to himself as "Prince Eugene Lascaris Comnenus, heir to the Emperors of Byzantium and Pretender to the Throne of Greece". To explain how an obscure Spanish laborer was the direct descendant of the rulers of the Byzantine Empire, Eugenio created a great genealogy c. 1935, notably changing his own familial history; his grandfather Victoriano was substituted for "Prince Andronikos Theodore Laskaris" who allegedly came from Greece and then settled in Italy (where he took the name "Victorio") before settling in Spain. Eugenio's great-grandfather Alonso was substituted for "Prince Theodore Laskaris, Porphyrogenitus". This first genealogy was contradicted by later genealogies in 1947 and 1952, which again changed the names of Eugenio's ancestors, added more supposed "princes" and altered their relationships. The last version of Eugenio's genealogy even changed the name of his father, claiming that Eugenio was the son of "Alexios VI Manuel". By 1952, Eugenio now claimed the name Eugene II Lascaris Comnenus ("Eugene I" being one of his many invented ancestors) and the titles "Prince Porphyrogenitus" and "Duke of Athens". Furthermore, Eugenio now claimed to be the Grand Master of the Constantinian Order of Saint George as well as some invented orders, such as the "Order of Saint Eugene of Trebizond".[51]

The genealogy presented by Eugenio is in part entirely fabricated and in part real, but with no connection to the Lascorz family itself. The 1952 version of the genealogy explicitly contradicts Eugenio's earlier versions, which he had attempted to get approved by Spanish courts. As part of his aspirations to become recognized as the legitimate heir to Byzantium, Eugenio obtained "recognition" by several courts in Italy, though these courts did not investigate Eugenio's claims, nor did they have the competence or authority to rectify someone as a claimant to the throne of the Byzantine Empire or the new Kingdom of Greece.[51] After Eugenio's death in 1962, his claim was continued by his son Teodoro (27 October 1921 – 20 September 2006), who took the "regnal" name Theodore IX Lascaris Comnenus (Theodore III–VIII being invented ancestors throughout Eugenio's genealogy), moved to Venezuela and propagated the idea that the Americas represent "New Byzantium"; where Christian faith, Western thought and Greek civilization will continue to survive.[52] Teodoro's son Eugenio (b. 10 October 1975), or Eugene III Theodore Emmanuel Lascaris Comnenus, maintains his family's claims.[53]

Marziano Lavarello

Marziano Lavarello (17 March 1921 – 7 October 1992), sometimes going by the name Marziano Lavarello Lascaris Paleologo (claiming descent from the Byzantine Laskaris and Palaiologos families) or Marziano Lavarello Obrenovic (claiming descent from the Serbian Obrenović dynasty), was an Italian man from a wealthy Genoese family of shipowners who proclaimed himself as "His Imperial Majesty, Marziano II" (the 5th century Emperor Marcian being "Marziano I"). Lavarello annually celebrated the anniversary of his "coronation" as emperor (a ceremony which took place in a Methodist church in Rome). Marziano's real ancestors, the Lavarello family, were a distinguished Genoese family and could trace their descent (albeit not an imperial one) back to the 14th century. Marziano, possibly on account of his mother having an affair with a high-ranking member of the Roman Church, grew up in the Vatican instead of in Genoa and repeatedly looked for prestigious lines of descent, beyond his own Lavarello line. In 1973 he published a genealogy which made him out to be a descendant of the Greek god Zeus.[54]

The legal system of Italy in the 1950s and 60s provided ample ground for imposters and claimants such as Lavarello, and many such as himself managed to secure limited legal recognition. Lavarello's titles, and his role as Grand Master of the Constantinian Order of Saint George, were recognized by a court in Rome on 10 September 1948, wherein he was referred to as "Imperiale il principe Don Marziano II Lascaris Comneno Flavio Angelo Lavarello Ventimiglia di Turgoville".[54] One version of Lavarello's claimed full title was "Titular Emperor of Constantinople, Despot of Nicaea and Bithynia, Grand Duke, Sebastokrator and Byzantine Patrician, Emperor of Trebizond, Sovereign of Cephalonia and Asia Minor, Porphyrogenitus, Imperial and Royal Prince Lascaris-Doukas, Grand Head of the House of Lascaris, the Ninth Dynasty of the Holy Roman Empire of the East".[55] Lavarello minted coins of himself with the inscription "Marcianus II Serviae Rex Romanorum Imperator Dei Sacratus Gratia".[56]

In 1952 there was a famous legal battle between two self-proclaimed emperors, with Lavarello's right to "rule" being challenged by a comedian and actor from Naples known as Totò.[54] Totò claimed the title "His Imperial Highness Antonio Porphyrogenite of the Constantinian Descent of Phocis, Achaia, Flavio, Duke Comneno de Curtis, Imperial Prince of Byzantium, Prince of Cilicia, of Macedonia, Darbiana, Thessaly, Moldavia, Ponto, Illyria, Peloponnesus, Duke of Cyprus and Epirus, etc., etc.". Both would-be emperors held court and distributed supposed Byzantine titles to their friends and supporters.[57]

Marziano spent the last years of his life living in a small apartment in Rome, having spent most of his inherited money on his "royal" lifestyle and ceremonies. He never married and died childless. Lavarello's funeral was at the Church of St. Nicholas in Rome, a Russian Orthodox Church, which still houses one of Lavarello's manufactured "imperial crowns".[54] Lavarello's claim is perpetuated to this day by Arcadia Luigi Maria Picco, born in 1958 in Iglesias, Sardinia, who alleges that Lavarello willed his "titles" to him in the absence of heirs of his own. Picco thus claims the title of "Roman Byzantine Emperor" and claims to be the head of the house of "Lavarello Obrenović Angelo Flavio".[58]

Peter Mills

Peter Mills (1927–2 January 1988), an Englishman from Newport on the Isle of Wight, was the last in the long line of supposed Palaiologoi in England claiming imperial descent. He styled himself as "His Imperial Majesty Petros I, Despot and Autokrator of the Romans, The Prince Palaeologus" and claiming to be the Grand Master of the Constantinian Order of Saint George and the "Duke of the Morea".[59] Mills based his claim on the lineage of his mother, Robina Colenutt (called the "Princess Robina Colenutt-Palaeologos" by Mills), the daughter of a plumber by the name Samuel Colenutt. Mills believed, though he could never successfully prove, that Samuel Colenutt was a descendant of William Colenutt, the son of a man by the name Richard Komnenos Phokas Palaiologos of Kolonet (Kolonet being assumed to be derived from Koloneia, an ancient Byzantine province) who supposedly settled in Combley on the Isle of Wight in the 16th century and died there in 1551. Richard was the son of a John Laskaris Palaiologos of Kolnet, who died at Viterbo in 1558.[60] This John ("John IX") was identified by Mills as the same person as the John who was the son of Manuel Palaiologos ("Manuel III"), the younger son of Thomas Palaiologos, and as the same John who is identified as a son of Thomas in the tombstone of the Theodore Paleologus who died in Cornwall in 1636.[61]

Mills often walked around the streets of Newport "with long flowing white hair, sandals but no socks and some sort of order or military award around his neck". When he died on 2 January 1988, aged 61, his claim to the imperial throne was taken up by his second wife and widow who then assumed the title "Her Imperial Highness Patricia Palaeologina, Empress of the Romans". Although several newspapers, such as the Isle of Wight County Press, The Daily Telegraph and The Times, printed obituaries of Mills, identifying him as "His Imperial Highness Petros I Palaeologos", his own son Nicholas denounced the idea that their family were of imperial descent, calling his father's claims a "complete and utter sham" and hoped that "the ghost of Prince Palaeologus might now be buried once and for all".[62]

References

- Poulakou-Rebelakou et al. 2012, p. 405.

- Pohl 2018.

- Poulakou-Rebelakou et al. 2012, p. 406.

- Phillips 2004, p. 162.

- Papathanassiou 2011.

- Treadgold 1997, pp. 453–455.

- Finlay 1854, p. 63.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 975.

- Nicol 1993, p. 44f.

- Reinert 2002, p. 260.

- Reinert 2002, p. 261.

- Reinert 2002, p. 268.

- Reinert 2002, p. 270.

- Runciman 1990, pp. 84–86.

- Hindley 2004, p. 300.

- Süß 2019.

- Nicol 1967, p. 334.

- Moustakas 2015, p. 85.

- Jurewicz 1970, p. 36.

- Varzos 1984, pp. 484–485 (note 27).

- Nicol 1992, p. 110.

- Nicol 1992, p. 111.

- Nicol 1992, p. 113.

- Nicol 1992, p. 114.

- Nicol 1992, p. 115.

- Nicol 1992, p. 116.

- Harris 2013, pp. 643, 651–659.

- Nicol 1992, p. 118.

- Nicol 1992, p. 117.

- Sainty 2018, p. 41.

- Nicol 1992, p. 122.

- Nicol 1992, p. 123.

- Nicol 1992, p. 124.

- Carr 2015.

- Potter 1995, p. 33.

- Piccirillo 2009, p. 33.

- Sainty 2018, p. 42.

- Nicol 1992, p. 121.

- Sainty 2018, p. 51.

- Sainty 2018, p. 52.

- Sainty 2018, p. 58.

- Nicol 1992, p. 119.

- Sainty 2018, p. 12.

- Sainty 2019, p. 410.

- Sainty 2019, p. 411.

- Nicol 1992, p. 120.

- Beales 1931, p. 101.

- Nicol 1968, p. v.

- Runciman 1985, p. 197.

- Nicol 1992, pp. 125–126.

- Pseudo Lascaris Princes.

- Feldman 2008, p. 135.

- New Byzantium.

- Marziano II.

- Campagnano 2001, p. 3.

- Bjeloš 2003, p. 59.

- Barzini 2017.

- Picco.

- Nicol 1992, p. 125.

- Nicol 1992, p. 126.

- Constantinian Order.

- Nicol 1992, p. 127.

Cited bibliography

- Barzini, Luigi (2017). "The Aristocrats". From Caesar to the Mafia: Persons, Places and Problems in Italian Life. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138523913.

- Beales, A. C. F. (1931). "The Irish King of Greece". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 51 (1): 101–105. doi:10.2307/627423. JSTOR 627423.

- Bjeloš, Nenad (2003). "Visoka vojna škola u oružanim snagama Jugoslavije". dinar. 21.

- Campagnano, Anna Rosa (June 2001). "O "Conde" Raphael Mayer, um benfeitor quase esquecido" (PDF). Gerações/Brasil: Boletim da Sociedade Genealógica Judaica do Brasil. 10.

- Carr, John (2015). "Epilogue". Fighting Emperors of Byzantium. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1473856264.

- Feldman, Ruth Tenzer (2008). The Fall of Constantinople. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0761340263.

- Finlay, George (1854), History of the Byzantine and Greek Empires from 1057–1453, 2, William Blackwood & Sons

- Harris, Jonathan (2013). "Despots, Emperors, and Balkan Identity in Exile". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 44 (3): 643–661. JSTOR 24244808.

- Hindley, Geoffrey (2004). A Brief History of the Crusades. London: Robinson. ISBN 978-1-84119-766-1.

- Jurewicz, Oktawiusz (1970). Andronikos I. Komnenos (in German). Amsterdam: Adolf M. Hakkert. OCLC 567685925.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nicol, Donald M. (1967). "The Byzantine View of Western Europe" (PDF). Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies. 8 (4): 315–339.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1968). The Byzantine family of Kantakouzenos (Cantacuzenus) ca. 1100-1460: A Genealogical and Prosopographical Study. Dumbarton Oaks studies 11. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. pp. viii ff. OCLC 390843.

- Moustakas, Konstantinos (2015). "The myth of the Byzantine origins of the Osmanlis: an essay in interpretation". Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 39 (1): 85–97. doi:10.1179/0307013114Z.00000000054.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1992). The Immortal Emperor: The life and legend of Constantine Palaiologos, last Emperor of the Romans. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41456-3.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1993). The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261–1453. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521439916.

- Phillips, Jonathan (2004). The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople. New York: Viking. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-14-303590-9.

- Piccirillo, Anthony Carmen (2009). ""A Vile, Infamous, Diabolical Treaty": The Franco-Ottoman Alliance of Francis I and the Eclipse of the Christendom Ideal" (PDF). Georgetown University - Senior Honors Thesis in History.

- Pohl, Walter (2018). "Introduction: Early medieval Romanness - a multiple identity". In Pohl, Walter; Gantner, Clemens; Grifoni, Cinzia; Pollheimer-Mohaupt, Marianne (eds.). Transformations of Romanness: Early Medieval Regions and Identities. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-059838-4.

- Potter, David (1995). A History of France, 1460–1560: The Emergence of a Nation State. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312124809.

- Poulakou-Rebelakou, Effie; Kalantzis, George; Tsiamis, Costas; Ploumpidis, Dimitris (2012). "Dementia on the Byzantine throne (AD 330–1453)". Geriatrics Gerontology International. 12 (3): 405–412. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00779.x. PMID 22122672.

- Reinert, Stephen W. (2002). "Fragmentation (1204–1453)". In Cyril Mango (ed.). The Oxford History of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. pp. 248–83. ISBN 978-0-19-814098-6.

- Runciman, Steven (1985). The Great Church in Captivity: A Study of the Patriarchate of Constantinople from the Eve of the Turkish Conquest to the Greek War of Independence. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-31310-4.

- Runciman, Steven (1990). The Fall of Constantinople, 1453. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39832-9.

- Sainty, Guy Stair (2018). The Constantinian Order of Saint George: and the Angeli, Farnese and Bourbon families which governed it. Boletín Oficial del Estado. ISBN 978-8434025066.

- Sainty, Guy Stair (2019). La Orden Constantiniana de San Jorge: y las familias Ángelo, Farnesio y Borbón que la rigieron. Boletín Oficial del Estado. ISBN 978-8434025059.

- Treadgold, Warren T. (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804726306.

- Varzos, Konstantinos (1984). Η Γενεαλογία των Κομνηνών [The Genealogy of the Komnenoi] (PDF) (in Greek). A. Thessaloniki: Centre for Byzantine Studies, University of Thessaloniki. OCLC 834784634.

Web sources

- "Imperial Military Order of St. George: History of the Order". www.orderofstgeorge.org. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- "Giorgio Quintini Paleologo: FRIENDS - His Imperial Majesty MARZIANO II". Giorgio Quintini Paleologo. 2015-05-19. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- "The Great Seal of the Lascaris Comnenus". www.new-byzantium.org. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- Papathanassiou, Manolis (2011). "Byzantine Reign Periods in Numbers". Byzantine Chronicle. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- Sainty, Guy Stair. "The Pseudo Lascaris Princes and Their Fantastic Claims". European Royal Houses. Archived from the original on 12 February 2005.

- Süß, Katharina (2019). "Der "Fall" Konstantinopel(s)". kurz!-Geschichte (in German). Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- "St. George and St. Stephen Imperial Military Nemagnic Angelic Constantinian Holy Order". www.mac-ro.com. Retrieved 2020-03-08.